The subversion of censorship by political documentary filmmakers in India

The first incident related to the censorship of a documentary in India goes as far back as 1930 when the footage of Gandhi’s Dandi March—shot by Bombay’s leading studios—was banned and confiscated by the British Police (Dutta 2013). The fear looming over the administration was that the footage would create a sense of euphoria and potentially garner support for the civil disobedience movement. Ironically, the situation in independent India, under democratically elected governments, has not changed much. The archaic colonial legacy of censorship continues to inform India even today, where the general assumption is that cinema has a direct relationship with its audience and provocative imagery, whether physical, sexual or otherwise, can potentially incite the masses to anti-social behaviour. There seems to be little or no nuance in the understanding of the actual impact of cinema, as a result of which films continue to be banned in a knee-jerk manner.

This attitude manifests itself in the power corridors of statutory bodies like the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) that regulate the exhibition of fiction and non-fiction films in India. Functioning under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, the CBFC uses the Cinematograph Act of 1952[1], the Cinematograph (Certification) Rules of 1983 to certify films under different restricted categories of exhibition.[2]As a disciplining measure, it uses Section 5B of the Cinematograph Act of 1952 which states that:

A film shall not be certified for public exhibition if, in the opinion of the authority competent to grant the certificate, the film or any part of it is against the interests of [the sovereignty and integrity of India] the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or involves defamation or contempt of court or is likely to incite the commission of any offense. (http://cbfcindia.gov.in/)

Governed by this principle, many documentaries over the years, especially those which expose state-sponsored violence against its citizens, have faced the wrath of the State and as a result have either been completely banned or censored in parts.

Through a theoretical lens, censorship has been seen as a phenomenon that allows the State to dictate a social code for acceptable behavior rather than a mere imposition of rules. Not only does it explicitly decree what shall and shall not be allowed for public access but also suggests a script defining what should constitute public morality and decency. Film scholar Annette Kuhn attributes a more dynamic character to this process by drawing on Michel Foucault’s framework of power relations. She suggests that censorship must be seen as a ‘play of production and prohibition’ where the assertion of power produced through prohibition makes it conducive for resistance to emerge and the tussle between the two gives rise to further acts of censorship. This makes censorship an ‘ongoing process of definition and boundary-maintenance produced and re-produced in challenges to, and transgressions of, the very limits it seeks to fix’ (Kuhn 1998, quoted in Ghosh 2011).

In the world of cinema, the ‘play between production and prohibition’, or between repression and expression, is primarily fought between the State and the filmmaker and by referring to their interaction as ‘play’, Kuhn paves the way for an inquiry into the performative aspect of censorship. She allows us to see the State and the filmmaker as two ‘players’ involved in, what appears to be, a cat-and-mouse game where the ‘production’ of certain strategies and tactics for a counter-attack is inevitable.

If we locate these games within the field of documentary practice in India, we see that there are primarily two positions in the campaign against censorship within the filmmaking community. One believes in boycotting the process of censorship altogether and given the size and reach of the community, it is possible for documentaries to survive without having government approval as such. Documentaries are able to survive with limited screenings in film festivals and educational institutions, and documentary filmmakers are not particularly concerned about never being eligible for a National Film Award, for which a censor certification is mandatory

The other side of the censorship debate believes that while State approval may not affect outreach in a big way, it at least ensures that filmmakers as citizens are on the right side of the law where it is mandatory for all filmmakers in India to pass their work through the censors. More importantly, having government approval ensures that those who organize screenings of controversial films—constituencies of volunteers, students, and theatre owners—are not put at risk as the police may stop public screenings and even confiscate equipment in the absence of a censor certificate. For the purpose of this article, we will look closely at strategies employed by three filmmakers, Anand Patwardhan, Rakesh Sharma and Amar Kanwar, as well as at a larger community effort against censorship aimed at safeguarding freedom of speech and expression.

Of the many documentary filmmakers in India, the most notorious for fighting legal battles with the State is Anand Patwardhan. His performance record shows that as many as seven of his films have been called into question with the CBFC demanding ‘cuts’ for sections in the films which could potentially disturb law and order in the country. Patwardhan’s career as a filmmaker started with his first film Waves of Revolution (1975), which documented the 1974–75 uprising of the people of Bihar during the Emergency in India. Given the political flux in the country, Patwardhan organized clandestine screenings of the film and in September 1975, cut the film print in different parts and smuggled them abroad to be reassembled and circulated among non-resident Indians. While the film remained underground for a long time, it was given a ‘U’ certificate only after the Emergency was over. Thereafter, Patwardhan continued to make radical documentary films and repeatedly fought legal cases in the courts. It is important to note that Patwardhan has, so far, managed to clear all of his films without a single cut.

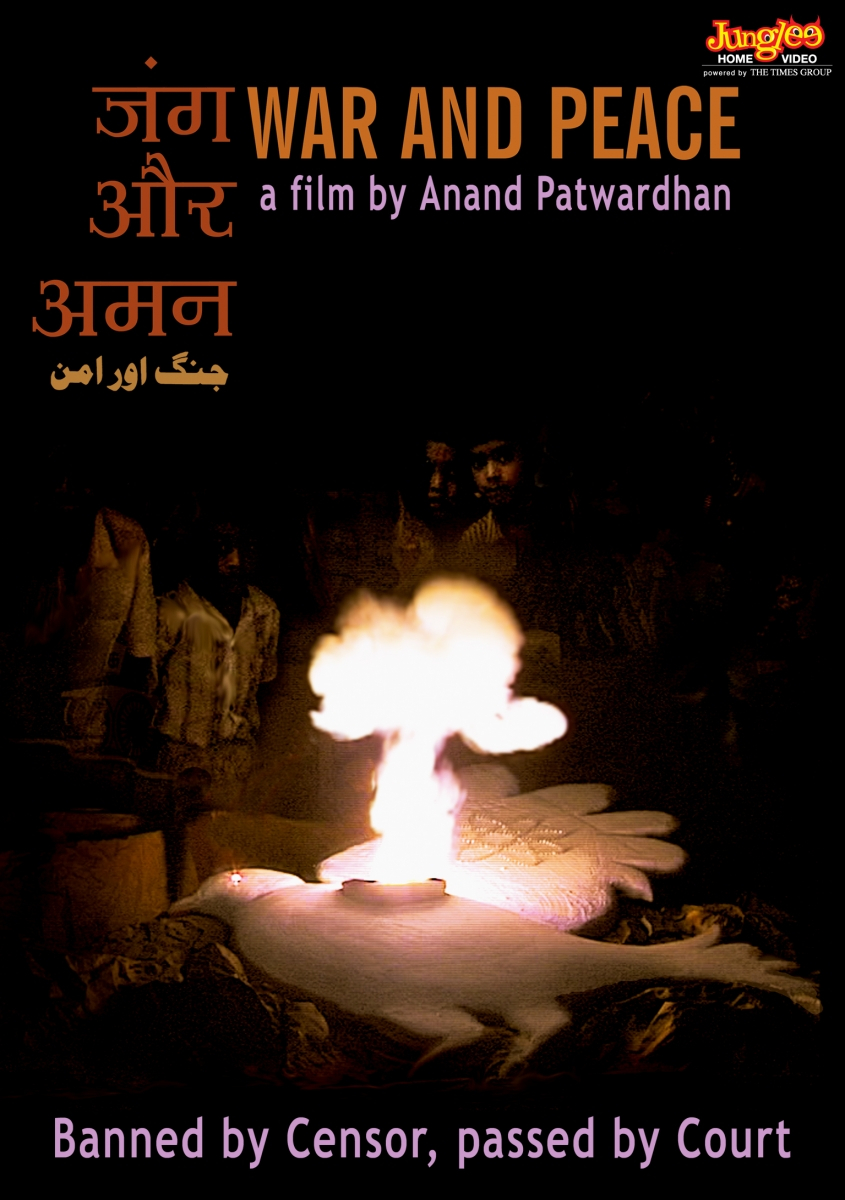

To understand Patwardhan’s tactics of dealing with the State, it is useful to take a specific example of his anti-war and anti-nuclear weapons film War and Peace (2002). The film, when first sent to the CBFC for certification, was not given a clearance and Patwardhan was asked to make 21 cuts, of which a few are described below.

|

No. |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Cut 1 |

'Delete the visuals of Gandhiji being shot by Nathuram Godse' |

|

Cut 2 |

'Delete the visuals of hands being cut with a blade and signing with blood by Hindus' |

|

Cut 5 |

'Delete the commentary, "BJP is faced with growing criticism"' |

|

Cut 7 |

'Delete the entire sequence, visuals and dialogues spoken by Dalit leader including all references to Lord Buddha' |

|

Cut 8 |

'Delete the reference to BJP uttered by villager.' |

|

Cut 9 |

'Delete the entire sequence and visuals and dialogues spoken by Dalit leader commencing from "Nathuram Godse high class (sic) brahmin ... high class killed him"' |

|

Cut 14 |

'Delete the RPI speech especially deleting the dialogue, "Not poverty but poor are eliminated"' |

|

Cut 16 |

'Delete the visuals of Hon'ble President of India, Dr. Adul (sic) Kalam.' |

|

Cut 17 |

'Delete the reference to BJP.' |

|

Cut 18 |

'Delete the entire sequence of Sadhaivi (sic) Ritambara including reference to Lord Rama.' |

|

Cut 20 |

'Delete the entire sequence of Tehelka wherever it occurs in the film.' |

|

Cut 21 |

'Delete the entire visuals and dialogues of all political leaders, including President, Prime Minister & Ministers' |

(Patwardhan 2002)

The aforementioned demands bluntly expose the bias prevalent within the CBFC especially at a time when the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) was in power. Clearly, Patwardhan’s film, which critiqued the nuclear arms race in the Indian subcontinent, did not fit into the script of the nation’s narrative of itself and therefore needed to be obliterated. Patwardhan approached the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), a statutory body which hears appeals of any applicant aggrieved by the order of the CBFC, which reduced the cuts to two and recommended one ‘addition’ to the film. Subsequently, Patwardhan filed a petition against the FCAT ruling in the Mumbai High Court. At the same time, in an unprecedented move, the CBFC sought an order to reinstate all the original 21 cuts, thereby challenging its own higher appellate body in the court.

In the situation that followed, the judges inquired as to what special interest the CBFC had in the matter of War and Peace that had prompted them to challenge the order of the FCAT. When no coherent reply was forthcoming the judges asked if the CBFC wanted to withdraw their petition. The CBFC withdrew their petition challenging the order of the FCAT and what remained in contention were the orders passed by the FCAT (Patwardhan 2003). In the final outcome of the case, the Mumbai High Court upheld the right of the documentary filmmaker to decide what should be included in the film and rejected the demands of the FCAT altogether.

Patwardhan’s attitude points not to an antagonistic relationship between the filmmaker and the State but rather to the potential in negotiating processes where democracy becomes the ground on which both can interact with each other and simultaneously, influence each other as well. ‘We have a decent Constitution so we must explore the law, push its boundaries and speak out if they are being violated. What’s the use of democracy if you’re not going to use the law?’ explained Patwardhan in a personal meeting with the author. Although Patwardhan’s constant tussle with the State has been effective in safeguarding the content of his films, it has also been able to generate mass publicity for him. It is also true that legal battles bring the documentary into the public gaze more vividly than the film might have otherwise. Former censor head Vijay Anand claimed that Patwardhan ‘wants the CBFC to try and ban his films so that he can get more media attention out of going public’ (quoted in Mazzarella 2013:154).

Whether he does or not is debatable but the fact that free media attention can be garnered around such cases, makes publicity a by-product of censorship. In this context, Patwardhan’s response to censorship becomes starkly performative in the noise he creates in the public domain. In fact, he is so widely known for his cases that the press reports about him even at times when a film like Jai Bhim Comrade (2011) is passed by the censors. Thus the performative quality of censorship becomes productive by way of creating loud noises out of intended whispers. This becomes an effective tool to be used by filmmakers to bring their films into the public domain, get noticed, and be watched by Indian audiences, thereby tactfully using this by-product of censorship to their own advantage.

In case of Rakesh Sharma’s Final Solution (2002) the CBFC decided to completely ban the film on the pretext that it could promote communal disharmony among Hindu and Muslim groups and that it presenteda picture of the Gujarat riots of 2002 in a way that jeopardized State security and threatened public order. Ironically, the film was presented the Jury’s prize for the Best Film at the National Film Awards in late 2007, citing its ‘powerful, hard-hitting documentation with a brutally honest approach lending incisive insights.’

In Sharma’s case, the members of the Advisory committee of the CBFC were reported to have taken several toilet breaks and attended to phone calls during the preview screening of the film. Thereafter, they decreed a ban on the film, a decision taken in three hours. Since a process of arriving at a judgment of a three and a half hour long film, if evaluated fairly, could not have finished as early as it did, Sharma used these findings to expose the Committee in the public domain. With the help of media publicity as well as Sharma’s pressure on the CBFC and the Minister of Information and Broadcasting, Final Solution was passed without a single cut.

For the duration that Rakesh Sharma’s Final Solution did not have a censor certificate, he started what was called the Pirate and Circulate Campaign where each person who received a free video CD of the film was requested to make five copies and circulate further. In a scenario where the State broke the rules by not giving him a fair screening process, Sharma, as a counter-attack, resorted to piracy during the period of suspension before the courts could intervene as referees. Through his campaign, Sharma distributed free VCDs to more than 10,000 individuals and offered copies to organizations working on issues of communal harmony.

In another example of an event organized by the Films Division at the India Habitat Centre in Delhi in early 2014, filmmaker Amar Kanwar was not allowed to screen his film The News before the audience. A couple of minutes before the scheduled screening, a notice was sent by the police to the organizers that the film could not be publicly shown as it did not have a censor certificate. In a situation where the audience had already assembled, Kanwar decided to take the opportunity to talk about the film and discussed problems faced by filmmakers because of censorship.

When seen through a performative lens, the interaction between the filmmakers and the audience, especially at a time when a screening is forcefully stopped, creates a sympathetic bond between the two. The filmmaker, standing in front of the audience, not only gives verbal a description of the film but also explains the political scenario in which it is situated. In this way, the filmmaker is able to arouse curiosity about the film and the audience is invited to experience problems faced by filmmakers. The script of the un-screened film also manages to successfully survive in public memory. It allows the audience to see (or not see) the film against the canvas of a larger political reality; an understanding that perhaps a mere screening of the film may not have been able to give.

It is interesting to note that until 2003, there was no consolidated effort to oppose censorship by the documentary film community of India. Only a few filmmakers fought individual cases against the CBFC and found little organized support from others. However, in 2003, when the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) tried to disqualify films depicting communal violence, filmmakers from different cities started a collective effort called the ‘Campaign against Censorship’. It was decided that a parallel festival would be organized in protest against the MIFF with the name Vikalp or an ‘alternative’.

The Vikalp initiative can be recognized as a moment that galvanized the documentary filmmaking community in India. The organization of an alternate film festival an act of resistance gave a platform to the filmmakers to publicly and collectively oppose censorship and stand in solidarity with each other. The Films of Freedom Festival (FFF) organized in 2004 in Bangalore employed a similar plan. This newly-found solidarity in the community, the collective stand against the repressive State machinery, and a sharing of tactics and experiences among the filmmakers was a big shift from the isolated battles fought within the community so far.

If we look at the given case studies andgraph the emerging strategies for countering censorship over the last decade, we can see a concerted effort by documentary filmmakers in India to expand their audience. From publicity generated by the legal cases and alternatives like Vikalp, filmmakers are trying to find newer avenues to broadcast their films. While Indian documentaries have been shown on Doordarshan for years now, in recent times, the private news broadcasters like New Delhi Television (NDTV) and Epic Channel have spared weekly slots for screening of documentaries.

A handful of films have also managed theatrical releases; however in both the cases, documentary filmmakers have often been unhappy with the screening slots allotted to their films as well as felt stifled by the high technical costs involved in theatre releases. While recent years have witnessed heavy funding coming into India from international broadcasters and funding networks, many are known to subscribe to a typical style of character-driven story with a defined narrative arc, a trend that is increasingly flattening regional and alternative aesthetics of storytelling, thereby consolidating the hegemony of the global west in the creative industry of documentary practice.

The other form of censorship recently witnessed in India is the unruly and unlawful disruption of public screenings of films by right-wing forces. These claimants to public cultural authority have already become infamous over the years for attacking cinemas playing commercial films such as Bombay (1995), Bandit Queen (1994) and Fire (1996). On several occasions such groups have forcefully stopped the screenings of documentaries, vandalized theatres and destroyed equipment on the pretext that such films malign Indian culture.

The growing cultural fascism in our country has now graduated to attacking political documentary films as well. In the recent past films like Ocean of Tears (2012), Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai (2015) and Caste on the Menu Card (2014) have been asked to be removed from collegiate screenings and film festivals. These occasions have seen the same stalwarts of the right-wing threaten filmmakers and organizers as well as destroy projectors and banners. The perpetrators of such vandalism almost never watched the films and raise disagreements in a civil manner. This also reflects the weakening sovereignty of the CBFC where having a censor certificate does not seem to matter.

Looking at the additional modes of indirect censorship it can be concluded that the game between the filmmaker and the State now stands to include newer players. The grounds of combat have also shifted and in this arrangement the filmmaker is in opposition to a trinity of different modes of censorship—the State, right-wing forces and the market. Therefore, in order to continue with the uncompromising legacy of political documentary films, the filmmaker will now have to develop new tactics to safeguard the sanctity of his/her film text, reach out to bigger audiences and fight for the right to freedom of speech and expression, which is shrinking lamentably in today’s day and time.

(An abridged version of this article appeared in the Journal of Literature Studies in January 2015.)

[1] In 2013, a panel headed by Justice Mukul Mudgal, former Chief Justice of the High Court of Punjab and Haryana, proposed a model Cinematograph Bill to replace the Cinematograph Act 1952 and provide a new legal framework for governing Indian cinema.

[2] These categories are: U (Unrestricted Public Exhibition), U/A (Unrestricted Public Exhibition—but with parental discretion for audience under 12 years of age), A (Restricted to Adults) and S (Restricted to any special class of people).

References

Dutta, Madhushree. 2013. ‘Narrating Actuality’, Frontline, October 18.

Ghosh, Shohini. 2011. ‘The secret life of film censorship’, Infochange India 22.

Patwardhan, Anand. 2002. '21 cuts demanded by Censor Board on War and Peace’, Online at http://patwardhan.com/wp/?page_id=588.