Komal Kothari, along with his friend Vijaydan Detha, founded the Rupayan Sansthan, after painstakingly putting together an enormous archive of audio-video recordings of folk traditions from Rajasthan. By offering a more local perspective on social groups, Kothari offered a history from below and brought into question several established narratives of Rajasthani society and its peoples. To appreciate his engagement with Rajasthani folk traditions, it is necessary to trace the trajectory of his work, the range of which covered folktales, musical traditions and instruments, caste practices, arts and crafts, and ecology.

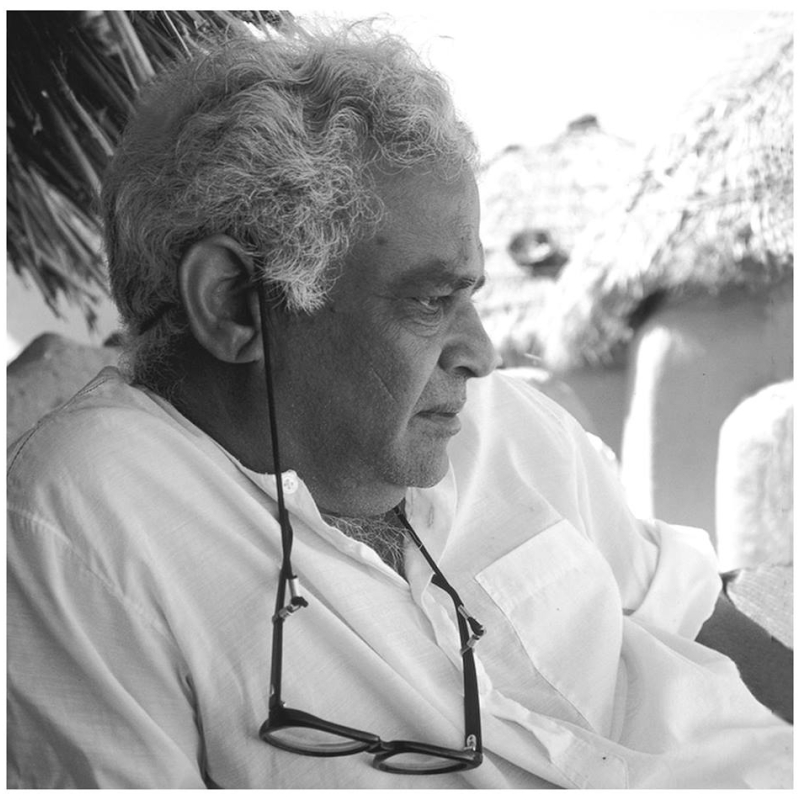

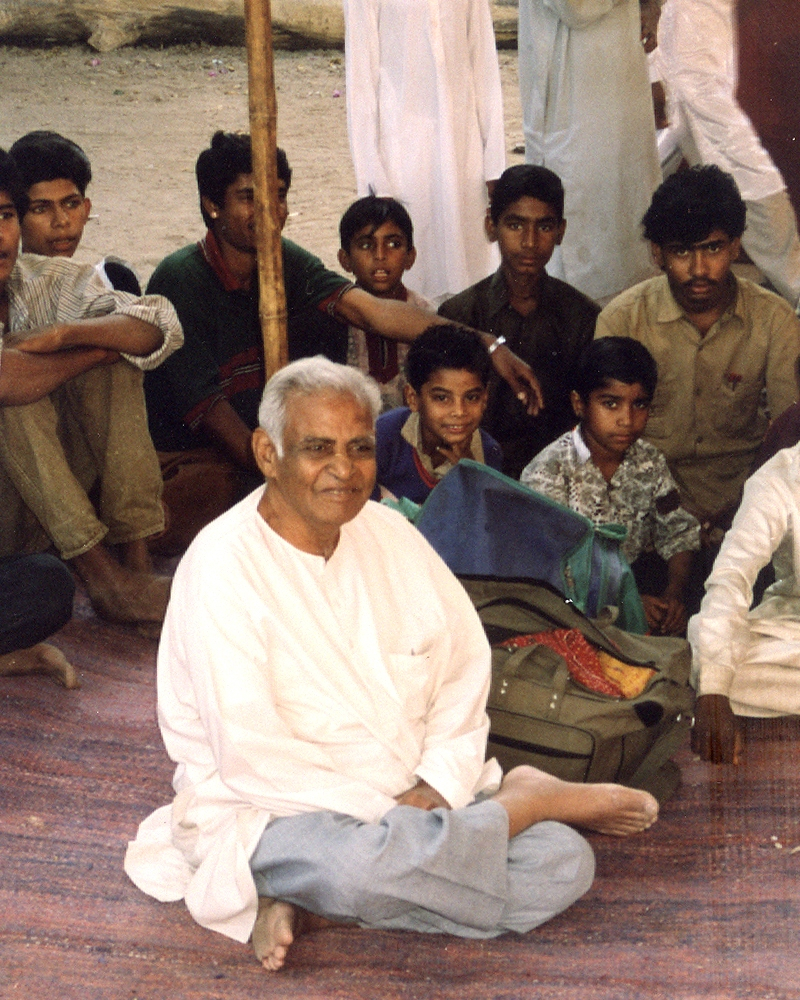

Fig. 1. Komal Kothari is seen here interviewing puppeteers from Nagaur in western Rajasthan. Throughout his career, Kothari used a very informal approach in his ethnographical surveys

This article attempts to ground Kothari’s work within three analytical themes. The first is the role of the Marxist intellectual tradition in influencing his ethnographical approach. Secondly, the essay places Kothari within the contradictory pulls of tradition and modernity by looking at his long association with professional caste musician groups such as the Manganiars and the Langas. Thirdly, it looks at his association with international and national organisations mediated through Rupayan Sansthan, where he endeavours to adapt folk music for a wider audience.

The Move to the Left

Kothari was associated with Left politics and was briefly a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The influence of the Marxist intellectual tradition is visible in his work in that his point of entry is rooted in the ecology and local modes of production. His research is distinct from the prevailing trends of Marxist scholarship at the time, because the 1950s and onwards were a period when the Left in India was yet to come to grips with the spectre of caste. Much of the Marxist literature is built around class analysis of society, where the rural and urban proletariat is said to be subsumed under the exploitative bourgeois state. Kothari broke new ground by placing Rajasthani folk culture within a distinctly ecological framework, where factors such as the geography, climate, soil and crops combine to influence ‘local’ modes of production.

The ecology of the Rajasthan region was divided by him into three characteristic agrarian zones, namely, jowar (sorghum), bajra (pearl millet) and makka (maize), based on the available supply of irrigation, quality of soil and nature of rainfall. Such spaces are said to be inhabited by social groups often ordered into castes and sub-castes, who are the prime carriers of local knowledge systems. These communities are spread over a region, which is alive with folktales that reflect both the epic and the mundane everyday struggles of these communities, and preserve the collective memory and shared history of the region.

Kothari felt that it is the state’s attempt to control the panch tattvas (‘five elements’)—fire, earth, sky, wind and water—which brings it into contest with local communities (Bharucha 2003:65). For instance, the drawing away of water for its use in the cities affects the water tables in ingeniously constructed water bodies in areas around Jodhpur. The scarcity of water affects the cultivation of the two most important staples of Rajasthan—jowar and makka. Moreover, much of the harvesting cycle in the region is dependent on the two spells of rainfalls that provide just enough moisture in the soil for the seeds to germinate.

For an example of Kothari’s attempt to explain the interdependent relationship between land and people, one may turn to his interpretation of the folk romance of Hir-Ranjha, popular across western South Asia, from Punjab to Rajasthan. It was composed by Waris Shah, who, according to Kothari, adapted it to the Sufi tradition. Folk songs and epics tend to be adapted to local contexts as seen in the case of the Dhola epic of northern India, a fragment of which, Dhola-Maru, is performed in western Rajasthan. Similarly, Kothari found that Hir-Ranjha is sung in the Alwar-Bharatpur region and is popular in mainly those areas that are prone to cattle epidemics. Although Ranjha was initially identified as a mahiwal or buffalo keeper he also became known for having special powers to cure cows. Such is the spread of his influence that at the time of cattle epidemics in the Braj region of Mathura it is he and not Krishna, the primordial keeper of the cows, who is remembered (Bharucha 2003:61).

A shift in geography brings with it a change in the context of songs and the use of different instruments. This is particularly true within the greater western frontier region (see the module, The Desert Frontier and the Arna Jharna Museum) The kamaicha (a bowed string instrument) is said to be played in grass-growing areas, prone to three to four inches of rainfall. The algoja (flute) is found in jowar-growing regions dominated by pastoralists. The sindhi sarangi, another string instrument, does not have such geographical determinants. It is used by the Langa musicians and found throughout Rajasthan, Gujarat, Sindh and Punjab. Just like instruments, even oral traditions are found to be located in specific agricultural zones. As mentioned earlier, Hir-Ranjha is associated with cattle-rearing areas whereas the bajra zone is where the oral epic Pabuji is found (Bharucha 2003).

Fig. 2. Kamaicha (photo by Dinesh Khanna)

Tanuja Kothiyal’s recent work suggests that oral traditions exist in a peripatetic zone, which also explains the shifting narratives found in the entire region of Sindh, Multan, Punjab and Rajasthan. Kothari would agree with Kothiyal’s approach in that she sees this large space as a region of constant movement (Kothiyal 2013:1–45). However, unlike Kothiyal, whose work is located in the 16th century, Kothari was engaging with the contemporary realities of Rajasthan. The trope of shifting narratives in Kothari’s work speaks of the crisis in water and grain management mainly by highlighting the role of a fast-declining material culture and its inseparable association with oral traditions.

Relationship with the Langas and the Manganiars

Kothari built a relationship with professional caste musicians such as the Langas and the Manganiars over a period spanning 40 years. It is through this lengthy association that Kothari was able to discuss and highlight the inner workings of caste, custom and patronage among these groups of people. These professional castes were a part of a larger network where professional groups offered their services to their patrons. By showing the similarity between ironsmiths, tanners and musicians, Kothari explained how within each profession there existed a complex set of responsibilities unique to the particular social group. Within caste musicians, too, there existed such a division of labour often defined by caste hierarchies and marital relations. The Langas and Manganiars were patronised through hereditary links, birat, or contract ayat (Bharucha 2003:218). The patron or jajman relations were unlike the professionalised arts where singers are selected to perform at large gatherings for a fee. In the case of the hereditary musicians, a patron had to honour his dues to an individual even if the latter did not have musical abilities.

Fig. 3. With musical traditions passed down orally, Langa and Manganiar children were initiated early into singing and playing instruments

Unlike schools of Indian classical music, which can be located within specific gharanas, folk music is unfettered by canons. Instead, it is styles of performing and practice which emerge from the social system that also enables the musical traditions to carry on. According to Kothari, in the case of the Langas and the Manganiars, ‘the transmission of knowledge are of a kind where nothing is taught, yet something is learned’. Just as the construction of natural water bodies, agricultural techniques and other ingenious vocational skills are passed down through generations, so is music, in no order of preference. The Manganiars, for instance, are endogamous with up to 80 sub-castes. Rules of marriage are disallowed within the same sub-caste and transgressions are dealt with violently. Kothari lists out several instances where women have been at the receiving end of sexual abuse, for going against customary norms.

Fig. 4. Until very recently, women were the mainstay of the Manganiar performing tradition. Shifts in the Manganiar social structure has made the repertoire male-centric

Much of Rajasthan guards itself through very strong notions of community honour, often leading to violence. Numerous scholarly works going back to the colonial period have highlighted the systemic violence of neoliberalism on local communities (such as Padel 2010; Guha 2000). Kothari’s own research introduces us to itinerant social groups like the Kanjars, who were brought under the punitive criminal tribes act of 1871 and continue to be treated with suspicion in the 21st century. The Kanjars were acrobatic women groups similar to the Nats and were traditionally associated with dancing before large village gatherings. Criminalisation of the community has made them wary of accepting payment in kind. The fear of being apprehended on the charge of possessing even a blanket, given as payment, makes Kanjar women insist on being paid in cash (Bharucha 2003).

In engaging with the Manganiars as a social system, Kothari had to be mindful about walking the fine line between intellectual engagement and strategic detachment. Numerous cases of violence were reported in instances where custom and tradition were said to have been violated. The binary entities, tradition and modernity, while useful to distinguish the rural and the urban, must perhaps be read in dialogue with one another. While discussing the issue of community and caste, Kothari finds it difficult to resolve the issue of transgressing social boundaries with the ease with which he explains the complicated relationship between the state and the people.

Fig. 5. Manganiars Dera Khan on the kamaicha and Ankla Devi on the dhol

National and International Engagement

For those of us whose understanding of culture is based on functions and events in the big cities, Kothari’s work appears as a useful guide towards contextualising ‘folk as people’ as opposed to ‘folk as exhibition’. Kothari engaged with a folk culture that shared a space comprising the Thar (and Rajasthan), Gujarat, Sindh, Multan and Punjab. This is contrary to the boundaries drawn out of administrative necessities carried out hastily and guarded viciously after the events of 1947. Kothari himself was mildly critical of how folk music was patronised by the state—princely Rajasthan and post–independent India. To him the timeless nature of folk traditions survived due to the expansive jajman system and the networks of trade, fairs, pilgrimages that made up everyday life in Rajasthan and the western frontier.

Fig. 6. Rupayan Sansthan is today overseen by Kuldeep Kothari, who continues to carry forward the vision of Komal Kothari and Vijaydan Detha

Kothari remained rooted in Rajasthan, his native place as well as his main area of research. This is not to suggest that he had a complete dislike for the market, on the contrary he was instrumental in internationalising Rajasthani folk music by having musicians perform in prestigious theatres to packed houses. Kothari sustained the workings of Rupayan Sansthan through a series of national and international collaboration, which included the Ford Foundation, the Sangeet Natak Akademi, and workshops and seminars (see sub-section ‘musical traditions’ in the overview article ‘Reimagining Rajasthan’). Numerous academics and writers owe a debt of gratitude to Komal Kothari for offering his observations on various topics of research concerning Rajasthan. Kothari was himself a reputed scholar, who left behind numerous publications in Hindi and English along with thousands of hours of interviews conducted by him across four decades, beginning in 1960.

Fig. 7. Women share an important space within Rupayan Sansthan as many of the indigenous and musical traditions have been documented from women informants.

***

Komal Kothari was a man possessed by an intellectual quest, and remained invested in speaking about, documenting and encouraging the oral traditions of Rajasthan until his demise in 2006. A few years before he died, Kothari conceived and established the Arna Jharna museum in Jodhpur. Spread over 10 acres of land, the open museum space recreates the desert space with its native flora and fauna, the jowar, bajra and makka agrarian zones, village architecture, sustainable living traditions, and galleries dedicated to brooms, musical instruments, puppets and pottery. The museum is a tribute to Kothari’s vision for an alternative history of Rajasthan. It represents the genius and imagination of a man who used a unique way of informing posterity of its rich heritage.

Fig. 8. Seen here are Kalbelia performers at the desert museum Arna Jharna. The Kalbelia community is the carrier of indigenous medicine and a rich repertoire of musical instruments

In the course of my research on Komal Kothari, I met many of his former friends and associates, and was struck by how often he was described as ‘a renaissance man’ or ‘a giant of a man’. Rustom Bharucha, author of Rajasthan: An Oral History: Conversations with Komal Kothari, may well have had the final word on Kothari’s legacy: ‘Like an oral epic, with no fixed beginning or end, Komalda lives forever.’

*The images in this article have been sourced from the archive at Rupayan Sansthan.

References and Further Reading

Bharucha, Rustom. 2003. Oral History of Rajasthan: Conversations with Komal Kothari. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Guha, Sumit. 2000. Environment and Ethnicity in India 1200–1991. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kothari, Komal. 1972. Langa Monograph. Jodhpur: Rupayan Sansthan.

Kothiyal, Tanuja. 2013. Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Neuman, Daniel, Shubha Chaudhuri and Komal Kothari. 2007. Bards, Ballads and Boundaries: An Ethnographic Atlas of Music Traditions in West Rajasthan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Padel, Felix. 2010. Sacrificing People: Invasion of a Tribal Landscape. Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Schomer, Karine, Joan Lerdman, Deryck O Lodrick, and Lloyd Rudolph. 2001. Idea of Rajasthan: Explorations in Regional Identity, vol. 1 & 2. Delhi: Manohar.

Wadley, Susan. 1983. '“Dhola:” A North India Folk Genre'. Asian Folklore Stories 42.1:3−25.