The joint efforts of two friends from Rajasthan, Komal Kothari, the oral historian, and Vijaydan Detha, the storyteller, formed, arguably, one of the greatest intellectual partnerships of post-Independence India. It was this partnership that found fruition as the Rupayan Sansthan, an institution dedicated to the folklore of Rajasthan established by Kothari and Detha in 1960–65.

The period under colonial rule was marked by the presence of numerous erudite and lettered Indian freedom fighters. The print culture that expanded in the 1920s would form the base for articulating divergent views on nationalism, gender and culture (Orsini 2009; Gupta 2002). By the time the British left in 1947, the written word had acquired a sort of dominance in the way civil society engaged with itself and with the state. Kothari and Detha, themselves a product of the freedom struggle, after spending many years writing pamphlets for the Indian National Congress party, laid great emphasis on documentation and writing as a means of historical inquiry. Their inquiry was into the folk culture of their native Rajasthan and, based in the village of Borunda in Jodhpur district, they set themselves the task of collecting and documenting folktales from all across Rajasthan. In the meanwhile, a larger movement to encourage folk traditions was gaining popularity post-Independence. As opposed to Hindi sahitya (literature), encouraged by the government through its various cultural organisations, stood the genre of lok sahitya (folk literature), an autonomous space created by dedicated folklorists to offer a counterpoint to the clamour around Hindi's adoption as the national language.

This article traces the institutional development of Rupayan Sansthan in terms of three interlinked themes. The first section explores the joint and individual trajectories of its founders, Komal Kothari and Vijaydan Detha, that formed the intellectual basis and, subsequently, contributed to the evolution of the institution. Rajasthan and, especially, the Thar are the constant backdrop to their efforts. The second section examines Kothari’s deep engagement with musician groups and the contribution of Rupayan Sansthan to the field of musical traditions. The third section pauses in the present and discusses the archive, the museum and the publications that continue Kothari and Detha’s alternative model for reimagining Rajasthan and indeed western South Asia.

The Intellectual Journey

The state of Rajasthan subsumes most of the Thar desert as part of a modern frontier state holding strategic importance for the Indian state. The Thar contains in itself the older regional divisions of Marwar, Jaisalmar, Bikaner and parts of Kutch, Multan and Sindh. For far too long, our understanding of Rajasthan has been a limited one, as the abode of princes in their forts and palaces, with entourages of courtly musicians and bards. Scant regard was paid to the wealth of performing arts and oral traditions of the region. This imagination of Rajasthan owes its relevance to literature produced during the colonial period, most noteworthy being James Tod’s Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, in which the colonial administrator-antiquarian offers a generous description of the Rajput community’s martial exploits (Tod 1920). Said to be of Scythian origin, compared to Anglo-Saxon knights, the Rajputs were portrayed as the most agreeable colonial allies in sedentarising, i.e. ‘civilising’, the desert region. The later efforts of Komal Kothari and Vijaydan Detha to document the folk culture were crucial as they offered a fuller, finer picture inclusive in the representation of the different communities of Rajasthan that also hinted at an earlier nomadic past. This extent of this nomadic past encompassed the greater region of western South Asia, including Multan, Sindh and Kutch, interlinked by a network of folk traditions and performing arts (Kothiyal 2013).

Punia is an example of a folktale that indicates the shared space of Rajasthan (Bharucha 2003:30−34). The story, recited by the Mukhbancha Bhats, caste genealogists from the acrobat community, reflects modes such as the satire used by lower castes to assert their claim on the land. The Bhats offer their storytelling skills to their patrons, the Bhambis, traditionally an untouchable caste within Rajasthan. Set within the Thar landscape, the eponymous protagonist, Punia, represents the earliest farmer to till land. The bards relate that the first crop grown by Punia was maize. On the day of harvest, he was visited by the sun and moon gods. On seeing them, he thanked the moon for providing the crop with cool nights and the sun for light to the crop during the day. Pleased with the show of gratitude, but not fully satisfied, the gods demanded their share of the maize. Punia said that they could take as much as they pleased. It is presented as a parody: the gods appeared to have never seen a maize harvest before and claimed the flowery tendrils on the top of the crop, eschewing the maize that grows on the stem.

The Bhats now takes the audience through to the next season when Punia grows jowar (sorghum). A similar turn of events is enacted with the gods arriving at the time of the harvest. This time, however, instead of the top, they demanded the stem, not knowing that the sorghum grows on the top. This is where the Bhats end the story, but not before asking the audience who according to them were the sun and the moon god. The audience is expected to reply, ‘the Chandravanshis and Suryavanshis [Rajputs]’. Thus, this tale is intended to take a dig at the feudal lord, usually, a Rajput claiming lofty origins from the sun and the moon. The intention is to show them up as usurpers, alien to the agrarian landscape of the region. The story is also representative of how the material and oral culture of Rajasthan is played out through a contest over resources which informs the historical narrative of communities living on the margins.

Starting out, Kothari and Detha chose to foreground their activities in a mixed-caste village in western Rajasthan on the edge of the Thar— Borunda. They collaborated with the villagers to raise funds and set up a printing press to bring out compendia of folktales. They began with documenting folk traditions for the various publications of the Borunda press. However, as their engagement intensified, it evolved along specific lines.

Kothari began to classify the performances, ritual and practices of different communities—such as the Langa and the Manganiar musicians, the Bhopa bards, and the practitioners of indigenous medicine, the Kalbelias—on the basis of style and language. However, even after a decade of doing this, he felt dissatisfied. He had failed to explain the economic basis that sustained these traditions. Their geographical spread was extensive but Kothari longed for a deeper understanding of the local context. He finally found inspiration in the work of the legendary anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss. Lévi-Strauss emphasised separating the realistic, such as geography, agrarian zones and climate, from the fantastical elements in oral traditions to arrive at a rational understanding of a culture (Lévi-Strauss 1978). Kothari adopted this method of investigation and revisited his archive of audio-video recordings. He examined the precise play of seasons, geography and landscape described in these traditions, and arrived at a classification of oral traditions into three agrarian zones: jowar (sorghum), bajra (pearl millet) and makka (maize) (Bharucha 2003). These zones, with their endemic flora and fauna, soil and moisture content, were used to explain the materiality of everyday life (from homesteads and granaries to utensils and brooms), and also provided the material base to locate a complex terrain of oral traditions. By aligning oral traditions with material culture, Kothari put forward a model for sustainable living and inclusive development alternative to the conflicted developmental practices of modern nation-building.

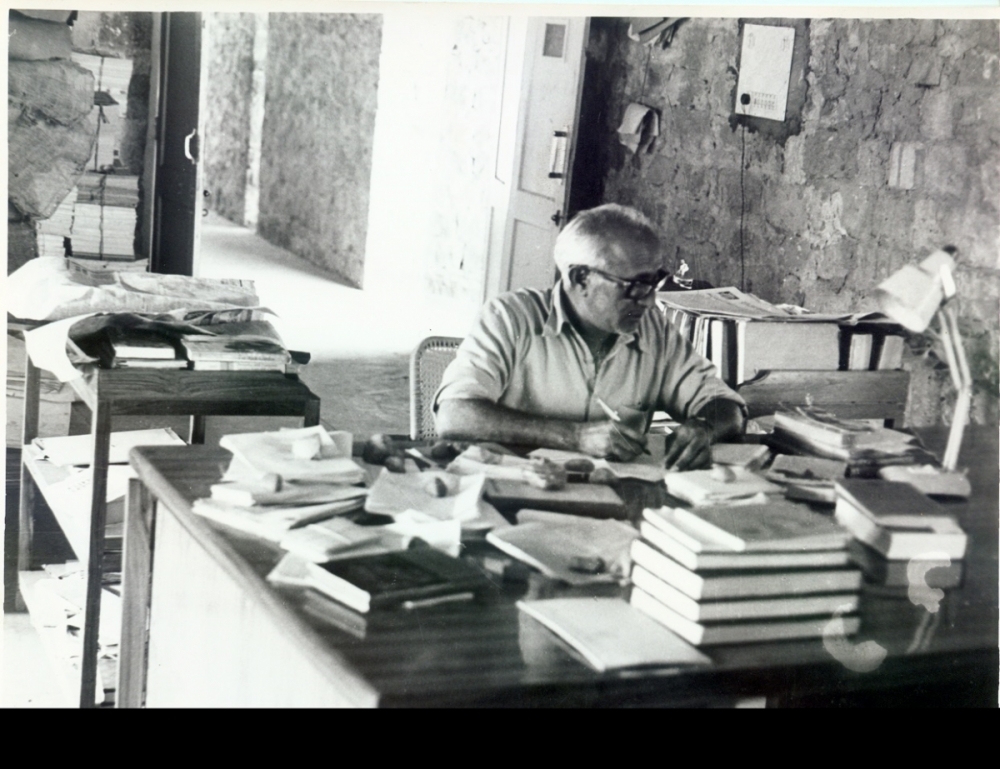

Fig. 1. Rupayan Sansthan conducted several informal workshops to document musical traditions and bring about a larger dialogue between various performative traditions

Kothari deployed the fable of 'Capturing the Clouds' to explain the anxieties of marginalised communities about conditions of manmade drought arising from the appropriation of natural resources, by either the traditional ruler or the developmental state (Bharucha 2003:82−84). Once upon a time, in the throes of a terrible drought, the tribal Bhil community prayed to the mother goddess to alleviate their plight. In response to these prayers, the goddess manifested herself before the Bhils and took them to the Bania’s house. Here, under the grindstone she found several clouds, which were then released into the sky. Soon it became dark and began to rain, to the delight of the Bhils. This tradition of ‘rescuing the clouds’ from the Bania is prevalent even to date as Bhils travel to Bania homes at the time of drought and demand that the clouds be released. In return, the Bania hands them gur (jaggery) and promises not to capture the clouds.

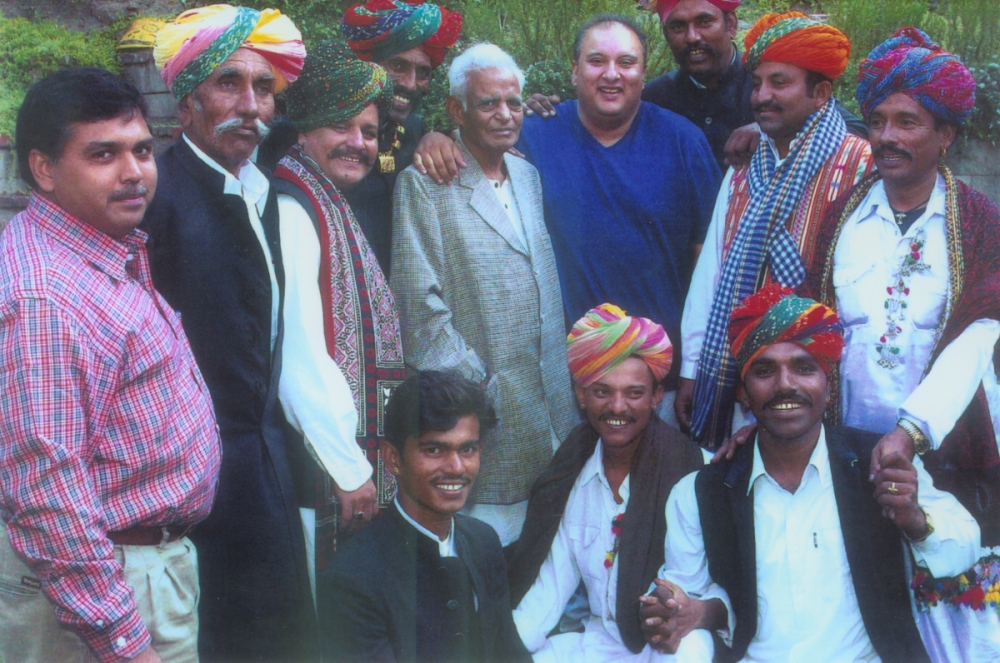

In the meanwhile, Detha was tackling ‘oppressors’ of his own. He set out by simply writing up folktales for publication in the journals Vani and Lok Sanskriti, and multi-volume Bataan ri Phulwari that came out of Borunda. A Charan by birth, he used the bardic community’s Chand storytelling technique to retain the performative aspect of the folktales in his adaption of the stories to the written word. Later, towards the end of Bataan ri Phulwari, as explained by his son Kailash Kabeer, he started to retell folktales putting his own progressive spin on stories that might skirt around issues but invariably ended up reinforcing orthodox conventions. What resulted are avant–garde stories that ‘speak out against satta (establishment)’, as represented by the feudal lord, the moneylender (or Bania), the patriarch and even the gods (Nair 2017). Some of his best-known short stories are stunningly feminist, espousing same-sex love between two women (Dohri Joon) or a woman’s right to sexual pleasure (Duvidha). Notwithstanding the weight of the message he delivers, Detha’s stories are narrated in a light vein, full of imagery that evokes the landscape, nature and seasons.

Fig. 2. Vijaydan Detha. Detha won the Sahitya Akademi Award for his 14-volume Bataan ri Phulwari in 1974

The Musical Traditions

Over the years, Rupayan Sansthan has come to have a special association with the performing arts of Rajasthan, which has evolved within the wider framework of cultural engagement refined by Komal Kothari. The material aspect of culture was vital to explaining the way musical traditions were performed using particular instruments, specific to different geographical zones (agrarian zones in the case of Rajasthan). The kamaicha (a bowed instrument), for instance, is associated with places growing a particular kind of grass, sevan ghas, the prevalence of which reflects more than four inches of rainfall (Bharucha 2003:89−93). The algoja (flute) is unique to areas that grow jowar and are inhabited, mainly, by pastoralists. The use of the sindhi sarangi (a stringed instrument), however, is not limited to a particular geography and is spread throughout the frontier region comprising Gujarat, Pakistan and Sindh in Pakistan (Bharucha 2003:90). Indeed, throughout western South Asia, similar instruments using the same musical principles and performance techniques are found.

Pabuji is a 14th-century epic hero belonging to the Rathore Rajput clan (Smith 1991). The Rathores established the Jodhpur state a couple of centuries later and drew up a grand genealogy linking their origins to Kannauj in north India. Contrastingly, Pabuji is deified by the camel- and sheep-herding Raika community living in the bajra zone and finds no mention in the genealogy of the royal Rathore clan. The epic emerges as the preserve of the lower castes, performed by the tribal Bhils. Pabuji represents a historical narrative that has allowed the Raikas and the Bhils to coalesce as social groups. The instrument used in the performance of the Pabuji epic is the ravanhatha (a fiddle-like instrument) and can be dated to a much earlier time (Bharucha 2003:90). Interestingly, it is in the 14th-century that the instrument becomes the sole vehicle used for the performance. However, little is known about the earlier musical traditions that it was used in before it became synonymous with the Pabuji epic. It is an example of the contiguous yet ephemeral nature of oral traditions.

Fig. 3. Pabuji is one of the most revered folk heroes of Rajasthan. The performing tradition of 'Pabuji ka phad' is performed over successive nights.

Most of the musical traditions in Rajasthan are sustained through strong networks of patronage. The Langa caste offers its service or kasbin to the Sindhi Sipahis, an agro-pastoralist community settled along the international border between India and Pakistan. The Manganiars who rely on the Rajputs for patronage also offer their service to other kasbin groups, high and low, servicing the Rajputs. Kothari documented many such traditions and revealed how these bonds were determined by birth, and might come under stress if the patron did not honour the customary dues owing to the kasbin. Kothari narrates episodes where a caste musician would cut off all ties by destroying his instrument at the site of his jajman’s (patron) village. He would then bury the instrument at the same place indicating that the bonds had been irreparably broken. This would signal the end of ties for all future generations for both the jajman and the kasbin. Such humiliating precedents explain why in most cases the jajman pays customary dues to his kasbins even if the latter is not a practicing musician.

The orally transmitted musical styles of the Langas and the Manganiar seem to have much in common with the classical Indian styles, probably imbibed under the influence of classical music in local courts (Neuman, Choudhary and Kothari 2006:105–11). The relation between folk and classical styles, instruments and vocals, is brilliantly explained in a short monograph on the Langa community by Kothari (Kothari 1972:14−20). For instance, Kothari placed folk traditions alongside classical music in an attempt to open up a dialogue between the two musical styles. Both genres have ragas, but, in the classical tradition, ragas have a set format, whereas, in the case of folk ragas, the singer may improvise within a loose framework (Kothari 1972:15). The Langas, on the other hand, have several ragas that appear similar to the classical genre but, on close scrutiny, reveal little in common. Even in recognising the musical scale, the Langa musicians have their own method and are unaware of the technique with which classical Indian musicians recognise the intervals and difference between the pitches.

Mindful of the dependence of professional caste musicians such as the Langas and the Manganiars on a fixed set of traditional patrons, and recognising the growing limitations of this way of life, through numerous workshops and concerts, the institution has encouraged musician groups to perform on a larger stage. Rupayan Sansthan has offered a platform for artists to achieve an international audience, performing at musical festivals and centres in the UK, USA, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, China, Japan and Pakistan, besides different parts of India.

Fig. 4. Kothari had a long and close relationship with several Manganiars and Langa musicians

Archive and Museum

The information available in national and region archives patronised by the state is usually of an official nature, presenting a statist view of policies, communities, time and space. Due to the overwhelming role of official sources, the interpretation of cultural themes such as ‘folk’ and ‘oral’ traditions have, traditionally, been understood within the concept of the nation state, and the folk is often subsumed within the defined culture of the nation. Arguably, regional culture as a theme is accommodated so long as it complements the majoritarian view, and offers styles and instances where the local, supra-local and regional intersect.

The category of a ‘living archive’, on the other hand, is one that is representative of an intellectual journey, and offers a deeper, more complex engagement with folk culture. By 2000, Rupayan Sansthan had acquired a corpus of mostly audio-video recordings and a small, but significant, collection of photos from the areas of ‘folklore’, ‘performing arts’, ‘sustainable living’, ‘indigenous knowledge’ and ‘arts and crafts’. This was also when the desert museum Arna Jharna was made open to public, offering a space to visitors to understand how oral traditions and the geography intersect in frontier zones like the desert.

The audio-video archive consists of recordings in the form of 3,083 audio cassettes, mini DVs, VHSs, SVHSs, spools, Hi-8s, DATs and mini discs covering 7,078 hours. Scholars from around the world have made use of the collection and have contributed to the archive by leaving behind a copy of their research in addition to transcriptions of interviews used by them. The monumental monograph by John Smith (Cambridge University), The Epic of Pabuji, was researched using the transcripts and recordings in the archive. Other scholars who have been closely associated with the Rupayan Sansthan through workshops, seminars and research are Susan Wadley (Ford-Maxwell Professor of South Asian Studies and Director, South Asia Center, Syracruse University) and Ann Grodzins Gold (Thomas J. Watson Professor, Religion, and Professor, Anthropology, Syracruse University). Vibeke Homma (lecturer in the Teachers Training College of Higher Education, Bergen) was long associated with Rupayan Sansthan as she spent many years studying oral transmission of the folk musical traditions of the Langa and Manganiar professional caste musicians in western Rajasthan.

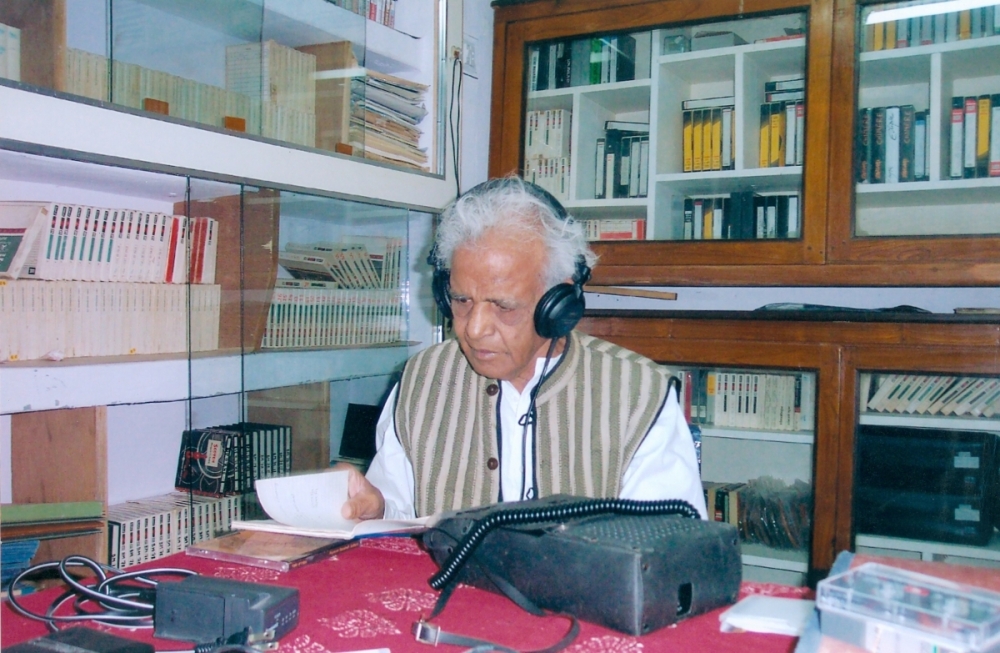

Fig. 5. The archive at Rupayan Sansthan currently holds 7,078 hours of audio-video recordings

In 2006, the ethnographical atlas of Rajasthan, Bards, Ballads and Boundaries, was published (Neuman, Choudhary and Kothari 2006). Written by Komal Kothari, Daniel Neuman (Mohindar Brar Sambhi Chair of Indian Music and Interim Director of the Herb Alpert School of Music, University of California) and Shubha Chaudhuri (Archive and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology, Gurgaon), the monograph includes a cartography and catalogue of musicians and music-making in the western districts of Rajasthan.

From circa 2000, a collection of musical traditions of Rajasthan were brought out in the form of CDs. These include Rajasthan: A Musical Journey, Tunes of the Dunes, Haunting Folk Melodies: Instrumental (vols. 1 and 2), Meera: Voices from the Desert of India, Banna: Additional Wedding Songs by Manganiars, The Folk Musicians of Rajasthan (vols. 1 and 2) and Desert Songs by Folk Musicians of Rajasthan (vols. 1 and 2), and selections from the archive, which include Master Musicians from the Archives: Sakar Khan, Master Musicians from the Archives: Karim Khan, Master Musicians from the Archives: Bhungar Khan (vols. 1 and 2) and Rajrang: Rhythmic Experiences.

Kothari had long envisaged a space to exhibit and bring about public engagement with the folk culture and oral traditions he had spent his life documenting for the archive. The enterprise would be marked by a devotion to the natural and organic resources of Rajasthan, the local communities and their local forms of knowledge, art and culture. He waited until he found the perfect spot, Arna Jharna, ‘forest and spring’, in the village of Moklawas, about 15 kilometres from Jodhpur city. Encompassing a rocky outcrop and a ravine, which includes an old stone quarry turned watershed, commanding breathtaking views of the rocky plains of the scrubland, the location embodies the harsh beauty of the Marwar region of Rajasthan. The 10 acres of the museum site are surrounded by protected forest areas, sacred spots, different kinds of villages and waterbodies. The site is a haven for desert flora and fauna. It includes nearly 30 different varieties of trees and shrubs—from the ubiquitous Babul tree to the endangered Phog tree, from the Tulsi to the Zijnni shrubs. It is laid with a variegated carpet of about 30 different kinds of grass in different shades of green, brown and yellow. The air is filled with the sounds of birds such as parrots, pigeons and peacocks, and the watershed is regularly visited by deer and peacocks.

Fig. 6. Towards the end of his life, Kothari conceived Arna Jharna: The Desert Museum as a unique space that captures the flora fauna, and all the unique aspects of life in the Thar

The museum is in keeping with Kothari’s vision for a ‘living museum’ that celebrates the desert and local adaption to life in this terrain (see interview with Komal Kothari in video gallery). Complexes of earth-red buildings in the local style of village architecture blend with the landscape. The museum also represents the antithesis of the palace/fort museums of Rajasthan, replacing galleries showcasing artefacts of princely lifestyle with galleries exhibiting objects of quiet beauty. Visitors to Arna Jharna are startled to find the main gallery dedicated to the different kinds of brooms from Rajasthan divided into ‘male’ brooms for outer spaces and ‘female’ brooms for inner spaces, indicating entire galaxies of rituals and beliefs associated with them. A series of videos also highlights the communities, labour, skills and even risks associated with broom production with a view to sensitising the audience. The second gallery consists of a matchless collection of musical instruments unique to western India, including popular instruments such as the ravanahatha, gujratan and sindhi sarangis, and the surinda, and some such examples that are no longer used or produced, such as the jantar, jogia sarangi and nagfani. When the musician groups from the region perform in the open spaces of the museum, they evoke the romance of nomadism, of travel across western South Asia.

Rupayan Sansthan understands the irreversibility of historical processes influencing social groups. This is perhaps why the founders were eager to document of folk and oral traditions, rather than offer alternative means of livelihood. Efforts at advocacy have been limited to such intervention as integrating indigenous musical traditions within the larger global culture of folk and classical music. Such an approach allows communities to earn their sustenance based on their traditional skills and also to face the vagaries of a rapidly changing economic system.

Komal Kothari and Vijaydan Detha’s contribution to the field of folk culture were recognised by distinguished organisations and the government of India. Kothari was awarded with India’s second highest civilian award, the Padma Bhushan, in 2004. Detha received the prestigious Sahitya Akademi award in 1974, given to the most outstanding books of literary merit, published in any of the recognised Indian languages. In 2007, he received the Indian government’s Padma Shri award, the fourth highest civilian honour. Many of Detha’s stories and novels have been adapted into plays and films including Habib Tanvir's Charandas Chor (1974–75), Prakash Jha's Parinati (1986), Amol Palekar's Paheli (2005) and Duvidha (1973) by Mani Kaul. However, although Kothari and Detha have left behind such a rich legacy (Kothari passed away in 2004 and Detha in 2013) of documentation, scholarship and dissemination, the focus of the founding generation of Rupayan Sansthan was on archive building. The focus of the present team is on formalising the institution, digitising the entire archive and making it easily accessible to researchers, as well as encouraging academic networks.

Kothari and Detha remained committed to Rajasthani folk culture throughout their distinguished careers. Their approach, however, was underlined by their individual interest in exploring the Thar, Detha through literature and Kothari through ethnomusicology. Within a decade of the setting up of the Rupayan Sansthan, both had adopted a distinctive approach in their understanding of oral traditions. Kothari’s interest in documenting the performative aspect marked him out as an important ethnomusicologist in the region of Rajasthan, while Detha made a name for himself as a seminal writer of Rajasthani stories. Through the archive, the museum and publications, Rupayan Sansthan maintains the relevance of their extraordinary legacy.

*The images in this article have been sourced from the archive at Rupayan Sansthan, with the exception of the banner image, a photograph of folk musicians at Arna Jharna taken by Dinesh Khanna.

References

Bharucha, Rustom. 2003. Oral History of Rajasthan: Conversations with Komal Kothari. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Dalrymple, William. 2009. Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India. London: Bloomsbury.

Detha, Vijaydan. 2009. Bataan Ri Phulwari. Jodhpur: Rajasthani Granthaghar.

Gupta, Charu. 2002. Sexuality Obscenity, and Community: Women, Muslims and the Hindu Public in Colonial India. Delhi: Permanent Black.

Kothari, Komal. 1972. Langa Monograph. Jodhpur: Rupayan Sansthan

Kothiyal, Tanuja. 2013. Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Nair, Malini. 2017. ‘Beyond Premchand and Manto: Hindi theatre is finding inspiration in the writings of Vijaydan Detha’. Scroll, May 23. Online at www.google.co.in/amp.s.amp.scrol.in/article/837265 (viewed on July 4, 2017)

Neuman, Daniel, Shubha Chaudhuri, and Komal Kothari. 2007. Bards Ballads and Boundaries: An Ethnographic Atlas of Music Traditions in West Rajasthan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Orsini, Francesca. 2009. Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaning Fictions in Colonial North India. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

Smith, John. 1991. The Epic of Pabuji. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Strauss, Claude Levi. 1978. Myth and Meaning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tod, James. 1920. Annales and Antiquities of Rajasthan, vols. 1–3. London: Humphrey Milford/Oxford University Press. Online at https://archive.org/details/annalsantiquitie01todj (viewed on June 14, 2017).