The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a settling down of the urban industrial haze that had enveloped economic and political centres all over the world. During those unsettling decades, cities were still shaping themselves vis-à-vis emerging industrial modern realities – primarily, increased demographic concentration within dense neighbourhoods.

Tenements of various kinds were being formed and created that were dedicated to absorbing working classes. New urban configurations needed workers, but could not always accommodate them into a space that was mostly controlled by the established elite and middle-classes. While workers lived in cramped quarters, the well off continued to occupy individual homes, estates and, at worst, apartment blocks, which saw an increase in number and modernization of form.

The working class tenement has been a much studied and documented typology around the world. The classical working class’ habitat is the 'barrack' as described by Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845). The production of this form of housing responds to the logic of optimization, where the workers are given only the bare minimum to keep them active. The rationalization of the means of production accompanies the rationalization of space in which the city becomes the prime locus of work.

In some contexts the barracks and tenements made way for mass housing projects. In other places, for example, in Italian cities, the Casa di Ringhiera typology of small rooms arranged along long corridors overlooking courtyards with shared toilets, emerged around the late 19th century. Even they however, were modeled on convents and other communal living spaces from an older era.

Similarly the Cortico, a building that had several rooms housing families, with shared toilet and other facilities was common in Brazilian cities, catering to similar working class populations for at least a couple of centuries.

The chawl in Mumbai is part of similar histories, with a structure that resembles these typologies but also shares as much in common with dormitories and hostels – including their overcrowded conditions. It emerged in the early 20th century and is typically a three to five storey building with long corridors and rooms for families arranged in a linear mode, with common toilets at the end of each floor. This particular typology is considered representative of the form as a whole.

However, the term chawl itself has a much wider range of references in a more colloquial sense. It can be used for various kinds of tenements, but is most effectively deployed to distinguish its micro-characteristics from the neighbouring settlement, especially when it is designated as a slum.

At one level, the chawl – or chaal –can be a space that is the urban home for a family that is typically divided between the village and the city. Dual household families are common in many countries with strong rural populations, which are part of a more dynamic exchange of time and space sharing. This sharing typically happens between villages and cities and is made possible by family support systems.

In such scenarios, there is one home in the village, often the ancestral and permanent home, and the other in the city. They are both part of a cyclical pattern of migration in which individual members of an extended family have different orbits of movement ranging from short term stays to annual visits. Or it could be from an adult life-time of work before a return to the village besides of course, a permanent settling down, which may be one of all these choices.

Such a huge bandwidth of possibilities is what characterizes rural urban lives for a majority of working class urban Indians. The story of the chawl is something that needs to be located within this narrative. For many it has been a reliable and secure source of urban accommodation in a biographical span that has - at the very least - a dual sense of belonging.

In cities like Mumbai, which worked (and still does) with a prejudiced narrative around slum tenements, aspiring to the chawl, while belonging to a life of constant movement between the village and the city, was also a very real way to step up the socio-economic ladder of mobility and become part of an emerging middle-class.

In a more global context, the workers' barracks typically became slums, especially with the corresponding increase of rural-urban migration, with families leaving the countryside to become part of the urban proletariat.

Either through political pressure via unions, or active state interventions, the lives of workers and their neighbourhoods changed. In that narrative, the path on which everyone was set was typically permanent urban living with absolutely no return to the oppressive rural village. In this kind of story, the workers tenement represented a stage in people’s lives that marked rural-urban transition in the sharpest way possible. In the most ideal sense, it was connected with recognising the industrial worker’s rights as an urban citizen and treating it as a stepping stone towards a more settled family life that came along with the rationalization of work-time and space sharing.

What Engels described in Britain remains somewhat valid in certain contexts of Mumbai even today – although with one crucial difference. As Cambridge historian and chronicler of the colonial working class of 19thcentury Mumbai, Raj Chandvarkar points out, the industrial proletariat here, never fully gave up the pull of the village. So while it was true that the industrial workers settlement - the chawl - thrived and was densely used, by workers and their families, this crowding of rooms did not mean that the workers had given up the village for good.

In fact it was not just families of workers who came to the city but entire villages sometimes. And yet, they were not fleeing the village permanently. This movement to and fro had been part of their lives for centuries. Even before Mumbai appeared on the horizon, many residents of Ratnagiri district were part of established circulatory migration trajectories. In the past, employers used to be armies, workshops, construction sites or working on other agricultural fields. Newly industrializing Bombay was one more alternative and in the early years of the past century, even sent recruiters for inviting labour who were reluctant to move to the city.

It is in this sense that the industrial workers settlement in Mumbai, while showing a similar rationalization of space, time, rights and political sensibility that Engels described also did something more. It consolidated communities and village ties, and made the presence of the rural family and community occupy urban space on its own terms, revealing a political trajectory that was distinct from Engels observations in Britain.

Family, community and village networks shaped contours in the city and this was expressed in different ways. Caste-based mobilization among the Dalits was ideologically motivated to fight against the caste system itself and its political resistance was aimed at fighting the continuation of caste in an urban context. Dailt writers such as Daya Pawar have narrated powerful memoirs which show the complex ways in which such transition was happening. In his biography, he points out how important it was for his mother to define the boundaries of her home as a chawl and distinguish it from the slum outside, notwithstanding the near identical and precarious of quality of life in both spaces. He also underscores the fact that the village was rarely forgotten.

The city equipped critical Dalits to emerge stronger and reinstate their identity on newer terms back in the village itself. So when fellow villagers came to share tiny spaces in the chawl to sleep when looking for jobs, when the corridors were filled with community brothers – the ideal was not to escape the oppression of the village alone – but to consolidate forces in the city and return to the village stronger.

Towards this end, Chandavarkar points out that a majority of industrial workers in early 20th century Bombay were almost exclusively from Ratnagiri district. All through their lives as factory workers they kept going back – especially during monsoon season, to help in the paddy fields which were labour intensive. They sometimes took leave for three to four months. Often their fellow family members or villagers would take their place in the factory in a circulatory relay of work obligations and often stayed in the same room in the city in that very chawl.

So not only were these spaces not a marker of transition from rural to urban lives, but in fact were a means to continue the active links between the two places.

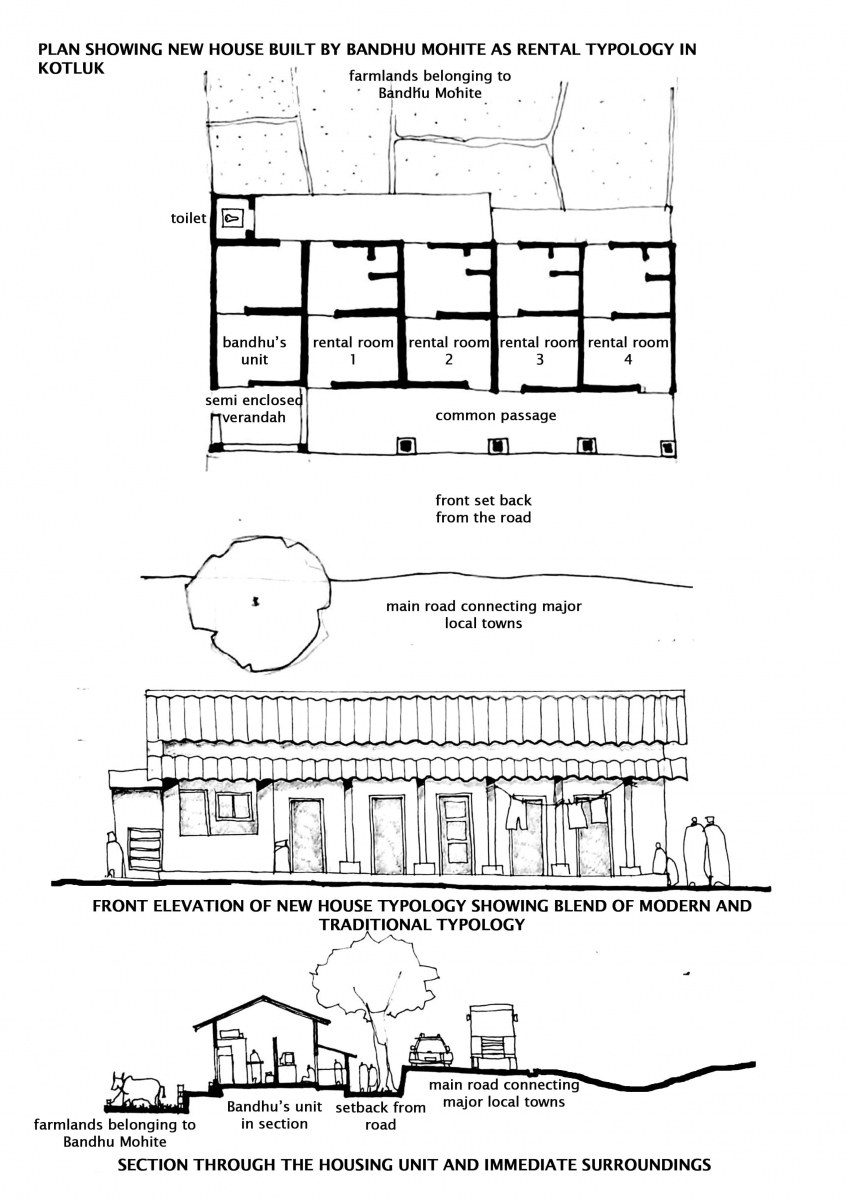

When the industrial houses and the government stopped building these chawls, especially after India got independence, immigrant workers under political patronage would continue to build rooms in the same form but in a different fabric – something more spontaneous and homegrown. A closer look at most homegrown settlements, urban villages and slums in Mumbai shows that a version of the chawl typology persists and is created and recreated all the time.

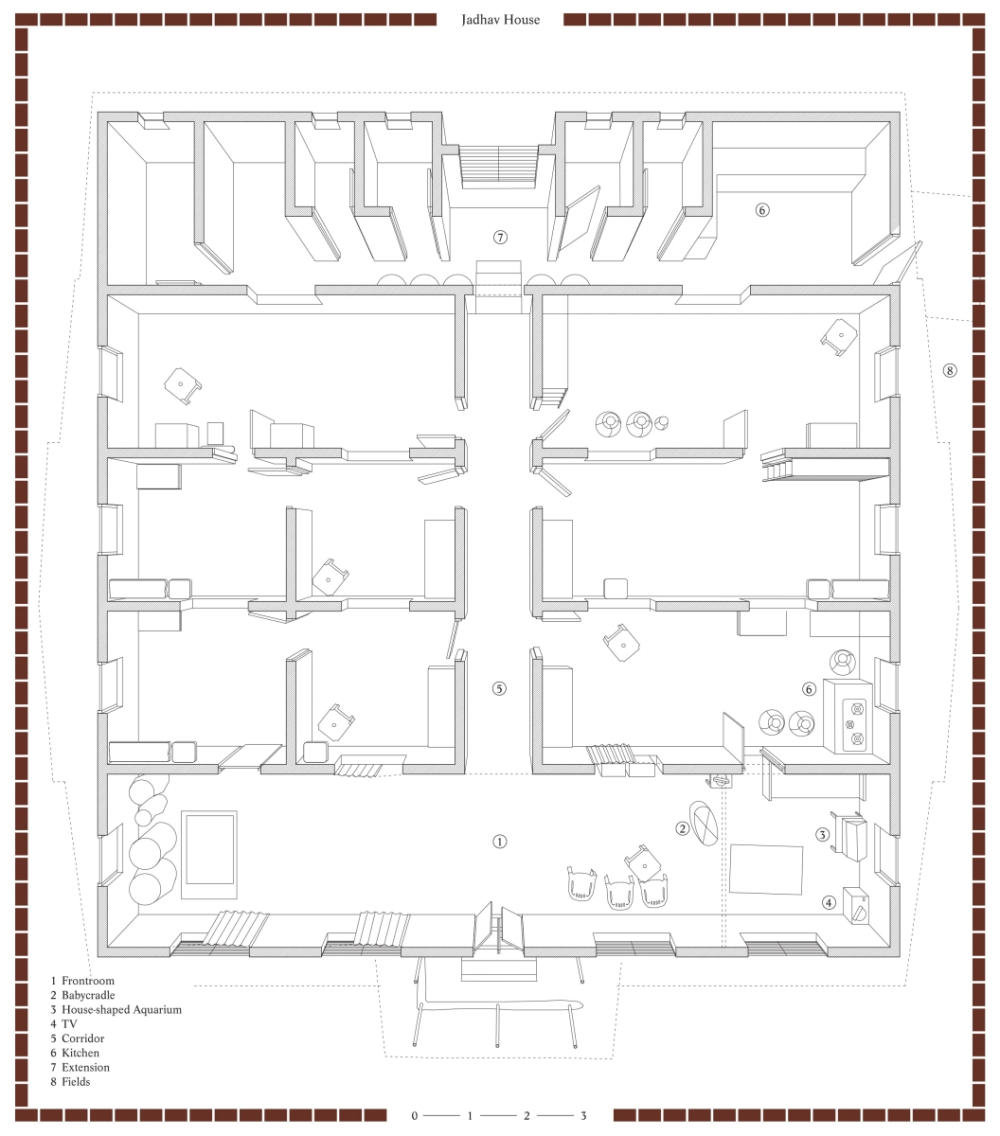

Even in the villages of Ratnagiri, on the other side of the migratory divide, in a newly built home, we can find an ex-Mumbaikar now based more permanently in the village who has designed his house in a manner reminiscent of the chawl.

In this more complex migratory trajectory, chawls can be seen as part of the urban need for accommodation that is a bit distinct from that of housing per se – though of course there is a connection.

Researcher Shreyasi Dasgupta speaks about a new type of building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Local builders there have created a stock of small rental apartments in mid-rise buildings that meets the demand of migrants on long cycles of work away from their villages. These structures are modelled on student housing and derive their name from the common place where students would eat together – the 'mess' which is were the typology gets its name – 'mess housing'. According to Dasgupta, 'Mess housing' is now very much part of Dhaka’s urban fabric and is here to stay. Its arrangements are diverse and are usually exclusively for males, females or separately for families.

This typology immediately evokes the Mumbai chawls but also the kudds or clubs of Goan migrants to Mumbai besides the musafirkhanas in the dockland neighbourhoods. Both the kudds and some musafirkhanas were often located within the chawl building, but were not organized through family units but instead through community ties. In fact, they were community based solutions for temporary accommodation in the colonial city.

The emergence of such spaces was also linked to the seasonal and cyclical demand for labour and skilled workers for specific periods and were nodes in a larger network of set-ups on the western coast of India. They could even belong to larger chains of operations going all the way to South Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

The fact that the colonial city had such institutions at a time when it attracted pools of migrants from all over the country and the world is something that needs to be connected to the chawl story, since they were all intertwined, often sharing the same physical space.

In fact, the Goan kudds connected the village to the city in a very strong way. Each village organized a kudd for its members and the urban institutions were actually named after the village itself. Thus, you had the Aldona Club or the Colvale Club and so on. The Musafirkhanas emerged more in the context of a supporting pilgrimage infrastructure but eventually became part of a local affordable hospitality industry.

When seen through this broader lens, the typology of the chawl can be connected to other forms of temporary accommodation meant for short and long-term visitors to cities. This list includes mess housing, chawls and kudds but which are themselves part of a larger universe of accommodation - hostels, dorms and army barracks.

Accommodation and housing are related but distinct needs. Recognizing this, in a context where migration tends to be connected to circular and seasonal movements of labour between villages and cities, will only create more realistic planning and regulations for cities in South Asia. In fact, a large percentage of city-dwellers all over the world do not intend to stay forever - they come for work, leisure, or learning and then move back or move on. This is as true in Mumbai, Berlin as in Seoul and Dhaka.

Chawls need not be relegated to Mumbai’s past life. They can be reinvented by developers and planners to produce new types of affordable temporary accommodation. They emerged historically at a time where there was a recognized response to accommodate migrant groups coming on different cycles of mobility and movement. The city still needs these spaces and such specific needs cannot be flattened into a demand for housing alone, which is usually part of a market-driven, speculation-fuelled demand for property ownership and not for creation of usable spaces.

Chawls can be located within the narrative arc of circulatory urbanism, which is India’s distinctive form of city-life, with one foot firmly planted in the village. The inner world of Mumbai’s chawls were full of stories of such connections and movements, especially from the Konkan coast. It is especially noteworthy that a slice of this world finds itself back in a small village in Ratnagiri district. It comes full circle.

Bibliography

Chandavarkar, Raj. From Neighbourhood to Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Left in Bombay’s Girangaon in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009

Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan. The Origins of Industrial Capitalism in India: Business strategies and the working classes in Bombay, 1900-1940. Vol. 51 of Cambridge South Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Deshingkar, Priya. Circular internal migration and development in India." Migration and development within and across borders: research and policy perspectives on internal and international migration, 161-87. Geneva: International Organization for Migration/Social Science Research Council, 2008.

Echanove, Matias and Rahul Srivastava. 'Circulatory Urbanism in Mumbai', in Empower - Essays on the Political Economy of Urban Form, Ruby Press, Berlin, 2014.

Gidwani, Vinay and K. Sivaramakrishnan.'Circular Migration and Rural Cosmopolitanism in India'. Contributions to Indian Sociology 37 : 339-367, 2003.

Iyer, Kamu. Boombay: From Precincts to Sprawl. Popular Prakashan Private Limited, 2014.

Nandy, Ashis. An ambiguous journey to the city the village and other odd ruins of the self in the Indian imagination. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Patel, Sujata, Masselos, Jim. Bombay and Mumbai, A City in Transition. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, India, 2005.

Shah, A. M. The writings of A.M. Shah: the household and family in India. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2014.

Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. 'The new mobilities paradigm.' Environment and planning A 38 (2): 207-226, 2006.

Singer, Milton B., and Bernard S. Cohn. 'Indian joint Family in the Modern industry' in Structure and change in Indian society. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co., 1968.