Typically, a chawl is a set of rooms strung along a corridor. Each of these rooms are inhabited by different households. Chawls can be single- or multi-storied—generally they have a ground floor plus two or three above. While one end of the corridor has a staircase, the other end typically has a set of toilets that are shared by the households. The entire building may also have a courtyard inside with corridor(s) running all around the courtyard.

There are many speculations about the origin of the chawl house-form of Mumbai. While the military barracks (where men lived in a string of rooms tied together with a corridor) are said to be the predecessors of the chawl; the agrarian house-type, the wada (typical in Maharashtra and other states of India), with a courtyard inside and a set of rooms strung along the courtyard, is an equal contender. Both genealogies seem equally convincing, as both forms existed in Mumbai before the first chawls were built. While the military barracks were easy to build, one can also speculate that the wadas lend themselves easily to becoming chawls as the economic activity of the city changed from agriculture to trade. The farmers rented rooms to traders who passed by the city. The word chawl also has two other significations—while it means a common street in front of one’s house, it also means a sieve (chaal). The warehouses that store onions, usually found near Nashik, are also called chaals as they have walls that are made of trellises and look like sieves. In many ways, the chawl housing, in form, is as porous as a chaal.

However, in our recent study of Gurgaon, we found the same chawl type emerging there to house the new migrant workers of the city. Gurgaon is a rapidly growing city near Delhi and a favourite of all business houses. In the past fifteen years, it has rapidly grown into a two million metropolis from a sleepy outskirt. It is a hub for most business process outsourcing companies. While there are gated apartment complexes for the corporate elite, it has developed chawls for the service providers—the labour that runs the city. These are typically developed by the old landlord farmers, who are left with some bits of lands inside old villages after giving away most of their (agricultural) lands to the developers of Gurgaon. The developers have used these large swathes of land to build call centres, offices and gated housing complexes. In Gurgaon, there were no military barracks or wadas. It appears that the simplicity of the chawl-type and an obviousness of its design makes it a default housing type to be quickly built for the needy. One finds such a type also in other parts of the world—particularly in Hong Kong. It is perhaps in the nuances and articulations that each chawl remains distinct from the other.

The purpose of this article is three-fold—first, to compile a series of different articulations in the chawl-type that produce distinct forms for housing; second to argue that the chawl-type produced a sense of community due to its form, and that this community had its particularities; and third, to argue that the chawl-type has much to offer for the emerging urban conditions in Mumbai and other cities of India.

The many configurations of the type

The term ‘type’ in architecture is a generic form of building. For example, a bungalow is distinct from a row house, which is distinct from an apartment, and from a hostel. These are all buildings meant to reside, but are different in form. They are distinct housing types. Though one can generalise that the chawl type is essentially a set of rooms with a corridor, architecturally, this type comes in several different configurations. And with each new configuration, there is a new spatial arrangement and a newer possibility for life to unfold.

The baithi chawl or the ‘sitting’ chawl, is the colloquial term for the one-storey chawl buildings that hug the ground and are laid out in several rows. These rows have fronts and backs. The fronts become active community spaces where people spend much of their domestic time. The backs become service spaces. As the interior spaces are small with generally a small multipurpose space, followed by a kitchen space, the building grows upwards to create a double height loft space that doubles up as bedrooms for newly married couples. Lofts also act as additional storage spaces that house large vessels used only during annual festivals. Baithi chawls in the Mill lands and other places where land was in abundance often also had small community spaces, large open grounds and other social amenities, which were actively used by the community. The baithi chawls in most places have become the first targets of redevelopment, as they occupy a lot of ground space, which is coveted as real-estate space.

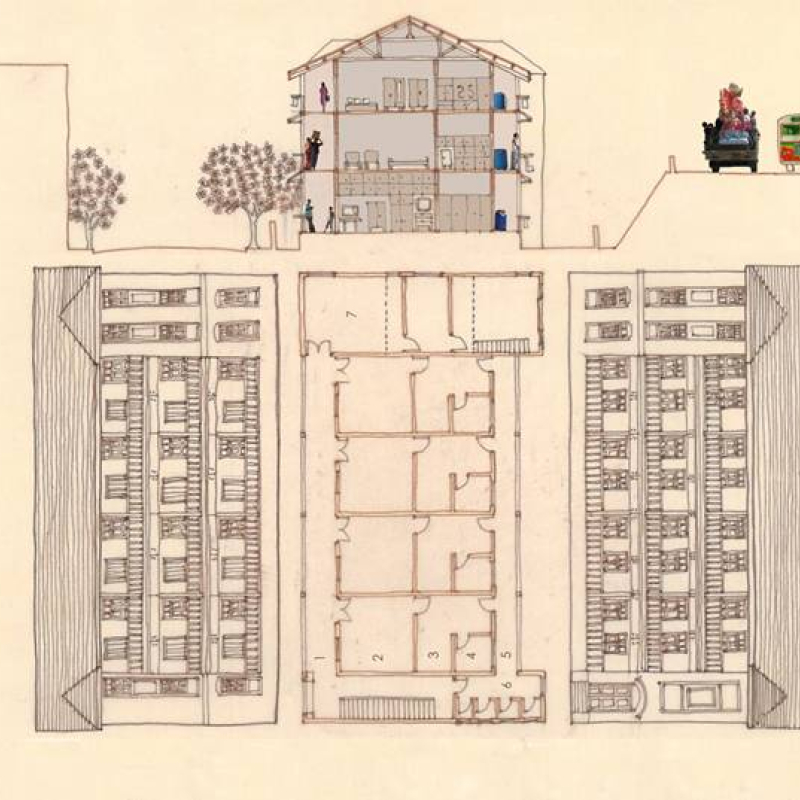

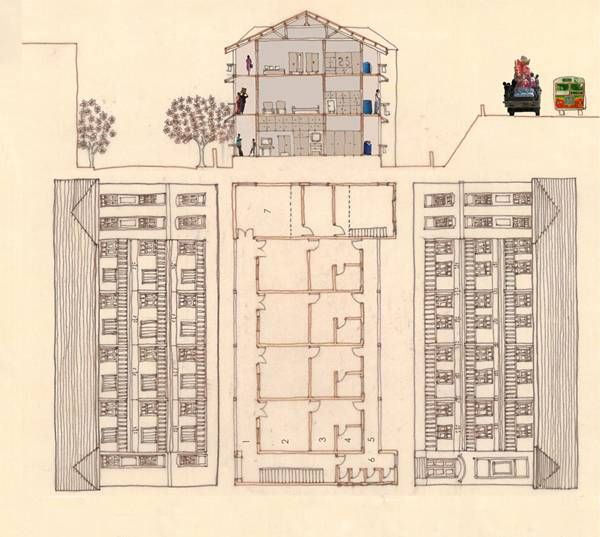

The bar chawl has a basic configuration and is typically multi-storied. It usually has two corridors stringing the rooms, one in front and the other at the rear. Most chawls are of this kind in Mumbai as they can be built on any configuration of land. The corridor, which has the main entrances of the houses generally, faces a street. By virtue of it being the shared access for all its residents, it often becomes a place that builds many community bonds. It is also the space where a lot of the household activities spill out, as the space inside is rather restricted. The toilet is generally at one end and the staircase that allows vertical circulation is at the other.

In this type of chawl, the interaction with the abutting street is significant and becomes one of the primary characteristics that shapes urban life. Sometimes, this kind of chawl has only one corridor—either facing the street or the rear. The bar chawls with single and double corridors function differently as the degree of access into the houses and shared spaces changes. The front corridors often become active semi-public spaces while back corridors are reserved for service functions. For example, the back corridor is where water is stored in large drums, where clothes are left out to dry and these are also the corridors that lead to the common toilets behind. While guests and other acquaintances come in from the front doors and the corridors attached to these, the back corridors are often the intimate spaces where daily chores are conducted. Women often prefer houses with corridors on both sides as houses are very small and it is the rear corridor where the stresses of the household are vented out.

In courtyard chawls, there is an open-to-sky space within the chawl, along which runs the corridor of the chawl. These open spaces, the courtyards, come in various sizes and shapes. Some chawls have many courtyards—for example, the Haji Kasam Chawl in Parel had five courtyards of different sizes with around 500 families living within. The courtyard is yet another shared resource, which becomes active during evenings on a daily basis and during festivals on an annual calendar. It eases the density inside a very tight internal space and allows the dense building block to breathe.

When the courtyards are very narrow and long, the corridors fronting the rooms get connected to each other through a delicate network of bridges. This reticulate system of access often becomes the heart of the housing, going beyond the function of movement as seen in the case of the Poonawala Chawl in Parel. These spaces absorb much of the outdoor living functions of the house. By virtue of the multiple homes spilling out their activities, these spaces become common living rooms of these complexes. Often the spilling out means those rooms are never locked. Both the front doors and the rear doors of houses are kept open such that one can easily pass through the front corridor, through the house, into the back corridor, into the bridge and back into the front corridor and the home of another unit. The porosity of the house not only helps release the density inside the otherwise tight living space but also builds many bonds between its inhabitants.

The courtyard chawls have a large footprint and are inward looking—the main space is the central courtyard. The space between two courtyard chawls remains inactive and is generally very narrow. Historically these spaces were often neglected and became the garbage dump yards where rats flourished. The British government found these spaces a source of disease. So in the 1920s when the British Government built new chawls to house workers, the ‘type’ of the building was significantly reconfigured. The narrow in-between spaces became the corridors with houses on both sides of the corridor and the courtyard became the space between the buildings, which was now very large and held the activities of the community. These double-loaded-corridor chawls were developed by the Bombay Development Department and are popularly called as BDD chawls now.

After independence and the partition of India, large numbers of people moved to Mumbai. There was a steep rise in the demand for housing in metros. In Mumbai, the Maharashtra Housing Board started building new housing stock to take care of the need for housing. This housing was adapted from the chawl typologies with single-loaded corridors that accessed each of the tenements. The toilets however were no longer shared and were accommodated inside the living units. The interior spaces, though slightly larger than the chawl houses, had a similar layout—a multipurpose room, a kitchen and sometimes one bedroom. However, unlike the chawls these were completely unadorned. They were made of reinforced cement concrete, very quickly put together. They also lacked any relationship to city edges or internal courtyards. Often one found these buildings rubber-stamped on available land with very little regard to urban design. The ground floors of these houses though contributed to an urbanity as people claimed space and made their exteriors liveable through multiple forms of occupation.

Chawl living

For about three hundred years from early 1700s to the late 1900s, the chawls remained the urban housing type for Mumbai—initially housing the traders and the trade workers and later built for the industrial workers. It had become a popular housing type for all strata of the middle classes. Chawls contributed to a very particular communal life, which is almost impossible to find in the other types—the bungalow or the apartment. The shared corridor that was used to access the rooms was the first to contribute to this aspect of communal living. One was bound to meet their neighbours while moving in and out of the houses. Secondly, on account of the compact sizes of living units one found that a lot of the activities inside the house made their way into the corridors, the staircases, the bridges and the courtyards outside.

The doors of houses were always kept open through the daytime and the evenings. The two doors of a room opening on two corridors—one on the public front and one on the private rear—made the rooms porous. People moved freely through these doors. An ailing couple, which would leave their doors open, would get multiple visitors through the day in the Poonawala Chawl. The porosity brought a sense of security to its inhabitants. In direct contrast to the apartment typologies, where one needs to keep doors locked for fear of theft, here the open rooms brought a sense of security both from theft and from that deadly human fear of loneliness. Common spaces became shared living rooms, which completely challenged the binaries of public and private spaces and the idea of what a home is, often making the entire chawl building into one large house. Private spaces happened only when the doors closed in the night.

One often found ingenious designs of doors that doubled as cabinet shutters as well as main doors. Main doors would be required to be closed only in the nights so they would often be multi functional. Here the compact spaces were negotiated with multipurpose furniture that folded away when not required making way for multiple daily activities to find space. Over the years one found orphan furniture, trunks and other paraphernalia that was left behind in the corridors, bridges, terraces, courtyards and other spaces, which belonged to no one in particular but became common property.

In 1947 with the large influx of people into cities and demand for housing rising, rents started skyrocketing. To protect people’s tenancy rights, the government froze all rents and prohibited eviction. This gave a sense of property to the tenants of the chawl, who consolidated their lives with the acquired permanence. The rent-control measure worked against the landlords who couldn’t make money from their premises any more. The landlords lost interest in the chawls. Soon, many of the other spaces in chawls began to be occupied—spaces below staircases, mid-landings and the lavish corridors. These found multiple occupancies for the local tailor, the ironing service, the electrician, etc. Over time these services became integral parts of the lives of the tenants.

Intense use and the advanced lives of many of these buildings started causing wear and tear. With very low rents the landlords did not have too many incentives to maintain their properties any more. The buildings started getting dilapidated. The government started collecting a cess tax from these older buildings, which could be put into their repair and maintenance. The Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) took up the responsibility of these repairs. However, often the repairs were not taken seriously. Much of the repairs involved selling off expensive wood found in older buildings and replacing with cheaper steel girders.

Stories of dilapidation of some of the buildings were mapped onto the whole inner-city precinct. These led to a policy intervention by the government to allow and incentivise the redevelopment of these buildings. This policy allowed any developer to approach the landlord and the tenants and offer to redevelop their properties. The developer had to give all tenants free housing in their new apartments commensurate to the area they currently occupied. In return they would be allowed to build 50 per cent additional area, which they could sell in the open market. This policy saw further amendments where more and more building rights were given as incentives to developers for developing these precincts. If the developer could convince larger numbers of people and amalgamate property, the developer got even more incentive as building rights. This new housing had to now accommodate parking norms. The policy also resulted in relaxation of set back regulations, which brought in adequate light and ventilation into buildings.

The resultant typology was often a tower with parking going up to six and seven storeys and the buildings so close to each other that often lower storeys would get very little light and ventilation. These norms also dangerously flaunted fire regulations. Often this relaxation did not allow fire tenders to enter the premises. While many tenants gave their consents initially to these developments, lured by becoming new owners of their rented premises, they found that the amounts that they had to shell out for maintaining these new properties were much more than their older houses. The maintenance now accounted for elevator charges, increased electricity to run these, water pumps and other updated infrastructure. Many would sell off their houses and leave for the northern suburbs, causing a soft gentrification of the precinct. But the story of dilapidation of the chawls appears to be put together to unlock the land under them and build new real estate. All buildings go through wear and tear. The buildings built in concrete in the 1970s seem to have a lesser shelf life than most of the chawls.

In recent times with the economy slowing down, these redevelopments have also slowed down. Hopefully this will lead to other alternatives, perhaps bringing back the culture of repair, retrofit to take care of this otherwise robust building stock.

The emerging city and the chawl

Since the 1990s, Mumbai’s population growth rate has been slowing down. It is a fraction of the national average. Between 2001 and 2011, some parts of the city have shown negative growth. The natural growth of the population on account of reproduction has been low like in all urbanised places. Not much inward migration seems to be taking place. If this trend continues, then in the next twenty years, Mumbai will be an elderly city. Moreover, in India, the absence of old age security makes things worse. For all these years, the family was seen as a security net for the older people, but with the increase in nucleation of families, the idea of family as a security net may not hold relevance.

On the other hand, the finance and commerce sectors, which were seen as replacement to the industrial sector, have not performed well enough to bring much wealth and employment. This is because of two reasons—first, there are many other cities that are competitively better in attracting new offices and headquarters; and second, the nature of work in finance and commerce has substantially changed on account of new technologies and contractual arrangements of work where dedicated ‘office space’ requirements have lowered. Mumbai, with its commercial and social infrastructure geared to work in the older modes and ways of doing business, seems to be losing out to places like Gurgaon and Hinjewadi. However, there are some sectors which are still doing well in Mumbai like apparel making, media, design, etc. These are all part of the culture industry. For Mumbai to be economically relevant in the next 20 years, it will have to encourage and nourish a culture-based economy and work towards creating an infrastructure to support such an economy.

For such an emerging condition of the elderly city and a new culture-based economy, the chawl housing type seems to regain its relevance. Here small compact rooms, with shared facilities, and an active community life, seems to be the model for the future. Can this older building stock be modernised with toilets inside, elevators for the elderly and multipurpose furniture to update this housing stock? The future lies in our midst.

Fig. 1: Bar chawl: Pradhan Building, Dadar

Fig. 2: Baithi chawl: Modern Mill Compound with social amenities

Fig 3: Poonawala Chawl responds to the city around