The Centre of South Asian Studies was founded in 1964, following the findings of one government commission and the recommendations of another—the government having been concerned about the fundamental lack of knowledge about other parts of the world, and thinking that an improvement in regional studies around the country would assist in this. As a result of these commissions, area studies centres were established at universities around the United Kingdom with ten years of funding provided by the British government on the understanding that the universities concerned would continue support after that initial decade. African Studies, for example, was established at SOAS, and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Hull. South Asian Studies was situated at the University of Cambridge.

With geographer Ben Farmer as its first Director, the Centre began establishing its reputation as a national and global hub for the study of the region. Its initial remit was to promote the inter-disciplinary study of South Asia in the University and across the UK. Subsequent Directors (Dr Gordon Johnson, Dr Raj Chandavarkar, Professor Chris Bayly and Professor Joya Chatterji) have seen this remit grow, with the Centre’s library and archive collections also now covering Southeast Asia, and with the Centre hosting its own Masters’ course from 2009, but the basic aim of all the Centre’s work remains the same.

Fig 1: The Centre of South Asian Studies in Laundress Lane

The Centre was initially housed in an historic warehouse building overlooking the Mill Pond in central Cambridge. With magnificent views and conveniently situated between two pubs, it was a very popular venue—some of the academic staff who were moved out of their offices in the building to make way for the Centre actually changed the locks in an effort to avoid being removed.

The Centre remained in this location until the end of 2011, when it was moved into a new building near the University Library, a building that is shared with the Centres of Latin American, African and Development Studies, as well as with CRASSH (the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities) and the Department of Politics and International Studies (POLIS). While the views are less spectacular, the purpose-built space is ideal for readers and for the archives, which are now housed in specially designed rooms with permanent environmental control.

Fig 2: The Alison Richard Building, which now houses the Centre of South Asian Studies

Fig 3: The archive papers room in the Alison Richard Building

The founding of the Cambridge South Asian Archive

In 1968 the Centre’s Committee of Management voted to establish a new archive collection, being aware that the generation of Britons who had lived and worked in India during the period of British rule of the country was diminishing in number. They appointed the Centre’s first Archivist, Mary Thatcher, who was instructed that she was not to collect the papers of ‘anyone famous’—the British Library was collecting papers at the same time, and there was a desire both to make the Cambridge archive distinctive and also to avoid treading on their toes.

Fig 4: Mary Thatcher in the archive rooms in the Laundress Lane Building (the image is a still from a film made for French television in the early 1970s about the Centre’s archive collections)

Mary set to her task with astonishing and characteristic vigour, writing to the mailing lists of the various associations and societies that existed in the UK at the time for those who had spent time in British India: the Indian Civil Service Association, the Indian Police Association and other similar bodies. She sent out some 3,000 letters, asking people if they had any family papers to donate to the collection.

As responses came in, Mary travelled round the country visiting potential donors, often staying with them for a couple of days, asking questions about their time in India, building up a detailed background of each donor and giving a context to the collection being donated.

As a result of this rather scatter-gun collection process, our collection is both eclectic and broad-ranging. There is nothing systematic about the way in which the papers were gathered—our donors gave us whatever papers they still had from their days in India, or which had been handed down through generations of a family. We have a collection, therefore, of what remains. Where we have papers about a specific subject that a researcher wants, it is more a matter of serendipity than design. We are very strong in some areas (the evacuation of Burma ahead of the Japanese invasion of 1942, for example), and have a lack in others. What we do have, however, is a strong collection about the life and work of the ‘average’ Briton in India.

Over the course of her 18 years as the Centre’s Archivist, Mary amassed a large collection. There are over 7,50,000 entries in the handlist of our paper collections (and this is not a page-by-page listing, so the collection is much larger than this suggests), we believe that we hold about 1,00,000 images in our photograph collection (although we will only find out the actual number when our digitisation project finishes, of which more later), we have 90 hours of film available online, with another 40 currently being catalogued, and the oral history collection has nearly 400 interviews comprising almost 1,100 hours of material.

We cover the whole period of British influence and rule. Our earliest document is from the 1630s (a ship’s log), but we are strongest on the period beginning with the 1857 uprising, leading into direct rule, up until 1947. As most of our donors left South Asia in 1947, our holdings diminish severely after that—there were quite a few Brits who stayed in Pakistan after 1947, so we have more about that country after Independence than we do about India.

At the time of writing (January 2018), we are undergoing a re-cataloguing process (visitors to our website will notice that the list of the papers is only partially complete, and that there is a point after which it is necessary to refer to pages from the old website for full information about a collection). Once this process is complete—probably towards the end of 2018—we will begin working on a backlog of new collections, and then we hope to start collecting papers from the South Asian diaspora in Britain. This would make our holdings slightly less British, and provide a balance which the collection lacks at the moment.

We group the materials Mary collected throughout this process into three basic types: papers, photographs and films. There is a fourth facet to our collection, audio material, which we will come to examine later. In the meantime, we will look at each section of the collection individually. It should be stressed, though, that most donations to the archive cover more than one type of archive: if we have a collection of papers from one donor, it is quite common for us to also have photographs or films (or both) from the same source. Given that we also have (in nearly every case) Mary’s detailed notes about the family history of the donor, and a personal account of their time in South Asia given at the time of the donation, our collections are quite exceptional in terms of the depth of knowledge we have of each family involved. Ours is, truly, a multi-dimensional archive, and our personal relationship with our donors and their families is unique and important.[i] The stories that surround many of the items in our archive are known to us, and to our readers, only because of the time and care Mary spent in developing this relationship—some of these stories will be revealed later in this article.

In the remainder of this article, I will examine each of the sections of the archive, giving a ‘tour’ of our holdings, under the four sections used in the catalogue on our website. I will give examples of different types of materials and links to where these resources can be found online. This overview will have the papers collection as its principal focus.

I must stress that the only sections of the archive which are available online are the film and oral history collections. We are working to digitise the photograph collection, but this is a slow process. The papers will never be put online (or at least not in my time as Archivist), but the description of our holdings in the online handlist will be improved over the coming years.[ii]

1: Papers

The papers form the largest part of the collection and they are the reason that most archive readers visit the Centre in Cambridge. The papers we hold are mostly very personal—diaries, letters, private notes, etc. During the process of collection, Mary Thatcher also gave out questionnaires to people who had interesting personal narratives to relate that were not in the papers being donated, particularly to women, as she had her own research interest in the lives of Memsahibs during the Raj. When a questionnaire was particularly interesting, Mary would ask the donor to write a memoir, amassing a significant collection.

Letters and diaries are the most common types of documents we have. However, these take many forms. I shall give a few examples by way of illustration.

Fig 5: Letters from the Campbell/Metcalfe Collection (Campbell/Metcalf: Box 2)

The letters in the image above are from a large collection (some 1,200 in total), mostly between Georgina Metcalfe and Edward Campbell, written between 1853 and 1861. Georgina and Edward had met and fell in love in 1853, but she was from a very high-ranking family and he, while a baronet, could only afford a captain’s rank (officers in the British Army and in the East India Company’s forces had to pay to achieve promotion).

This was not good enough for Georgina’s father, so he forbade them to have any contact with each other. Georgina wrote a letter every day, but didn’t send them so as not to disobey her father.

After a year of this, her father relented and the couple began to exchange letters and later married. They continued to write to each other (her a lot more than him!), and when he was sent around the country into action during the 1857 uprising, the letters took on a rather frantic tone. He survived and they went on to have a family together.

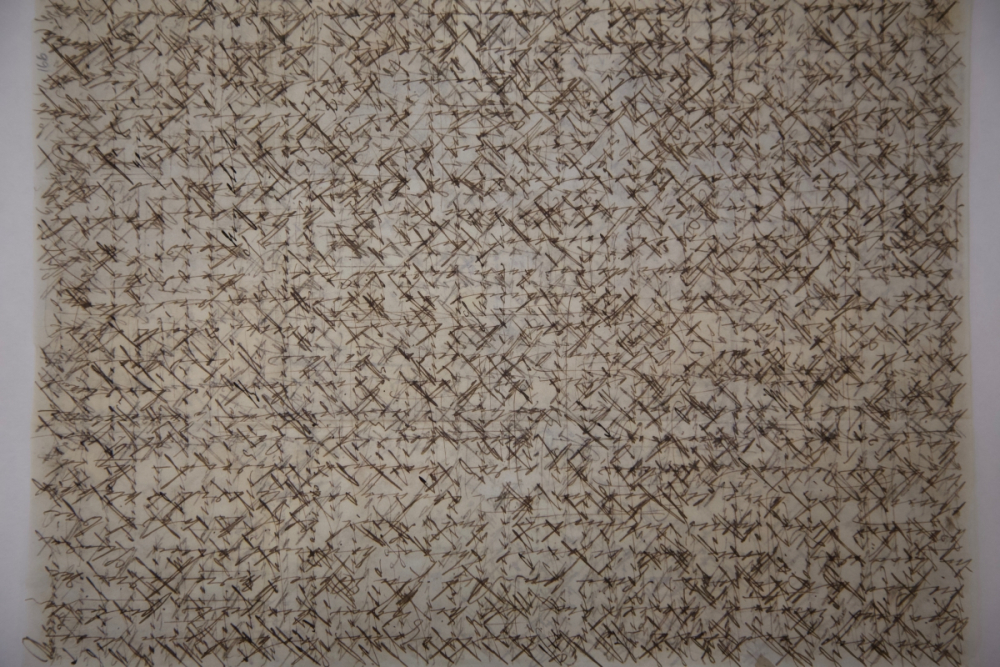

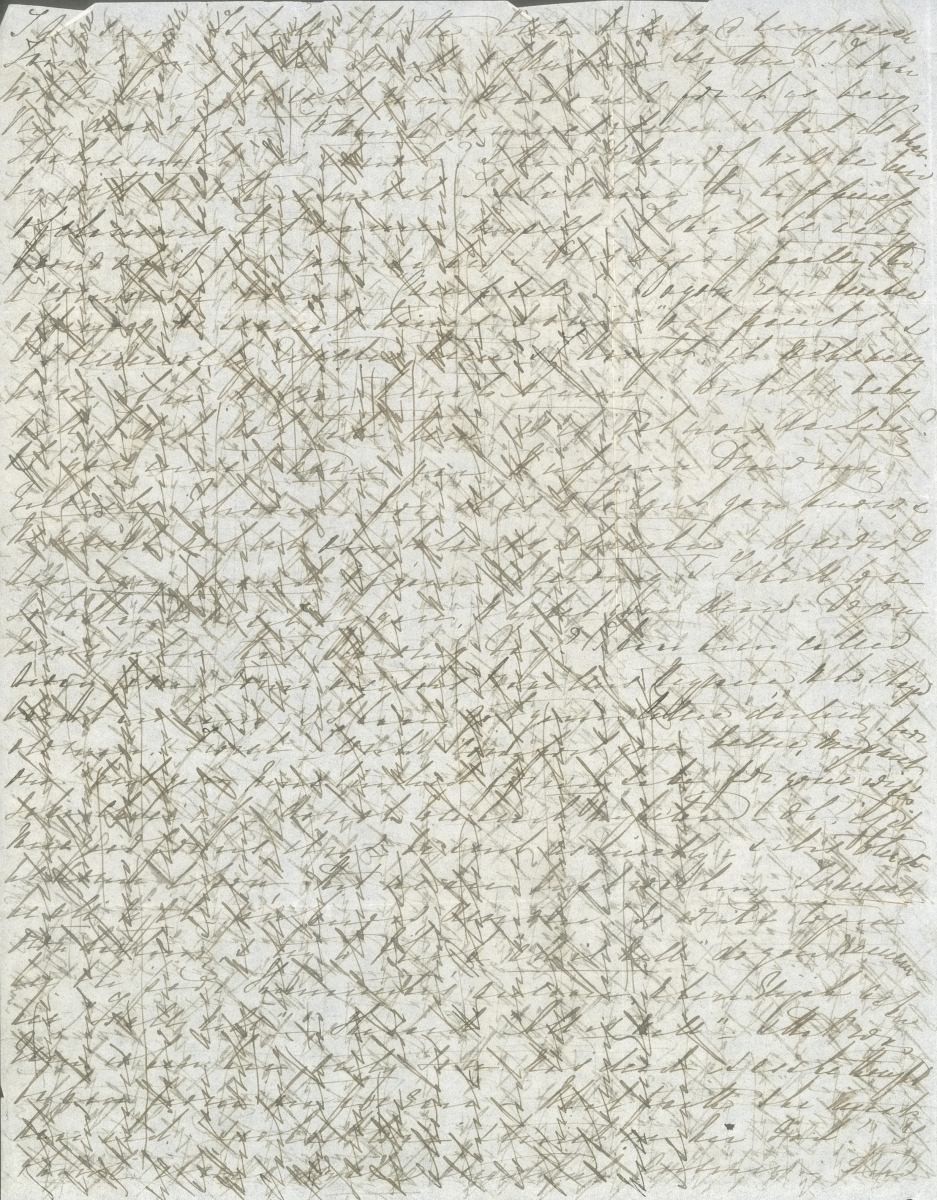

Fig 6: Cross-written letter (Campbell/Metcalfe:Box 3)

As a collection it is not terribly easy to read. Her handwriting is dreadful, and a large number of the pages are cross-written. This is where, to save paper, the writer would fill a page with text and then turn it through 90 degrees and write over the same page again. To read such letters, you take two sheets of paper and cover the letter with a gap between the two sheets, revealing the line you are reading at the time. It is extremely slow-going.

Fig 7: The last page of a cross-written letter. In this example, you can see that the letter ends with the vertical text in the image only having covered three-quarters of the page, leaving part of the page with text in only one direction on it (Campbell/Metcalfe:Box 2)

We have large collections of more easily readable material as well. Among them are those from Sir Edward Benthall reporting back to the Madras Chamber of Commerce on progress at the Round Table Conferences, giving frank accounts of his meetings with Mahatma Gandhi and interesting insights into the ways in which the British government was attempting to manipulate the various parties at the talks in order to achieve their own ends (Benthall: Boxes 1–6). We also have letters between Sir Malcolm Darling and E.M. Forster. Darling was a senior ICS. official and friend of Forster’s from their time in Cambridge. Darling was the person who invited Forster out to India—asking him to visit him in Dewas, the visit was to result in the publication of the book The Hills of Devi (Darling: Box 23).

Most of our letter collections are more mundane—most often letters describing life in India to people for whom the daily experience of the British in India would have been simultaneously unusual and familiar. The letters often describe religious festivals, social norms and other aspects of Indian life which would have been ‘exotic’ to readers back in the UK (for example, Vernede: Boxes 1–4), but they also relate the aspects of life in India where the British had established customs and practices which replicated life back at home: the club, dinner parties, afternoon tea and many, many other facets of British life in India would have been entirely familiar to those receiving the letters (see Scott, N.:Box 1).

Diaries also feature heavily in the collection. Most often these are personal records of daily life, but there are also a number of official diaries kept by I.C.S. Officers or Medical Officers as they went on official tours of their districts as part of their duties. These would then be transcribed to form part of the report submitted to higher authorities (see for example, Banks: Microfilms 75a and 75b).

Other diaries are more unusual. We have one collection, for example, which is one of the few holdings we have from an Indian donor, from a senior bureaucrat who kept a record of every expenditure he made, in the order in which they were made. We hold diaries of his spending from 1911 to 1962 (although it is not a complete run).

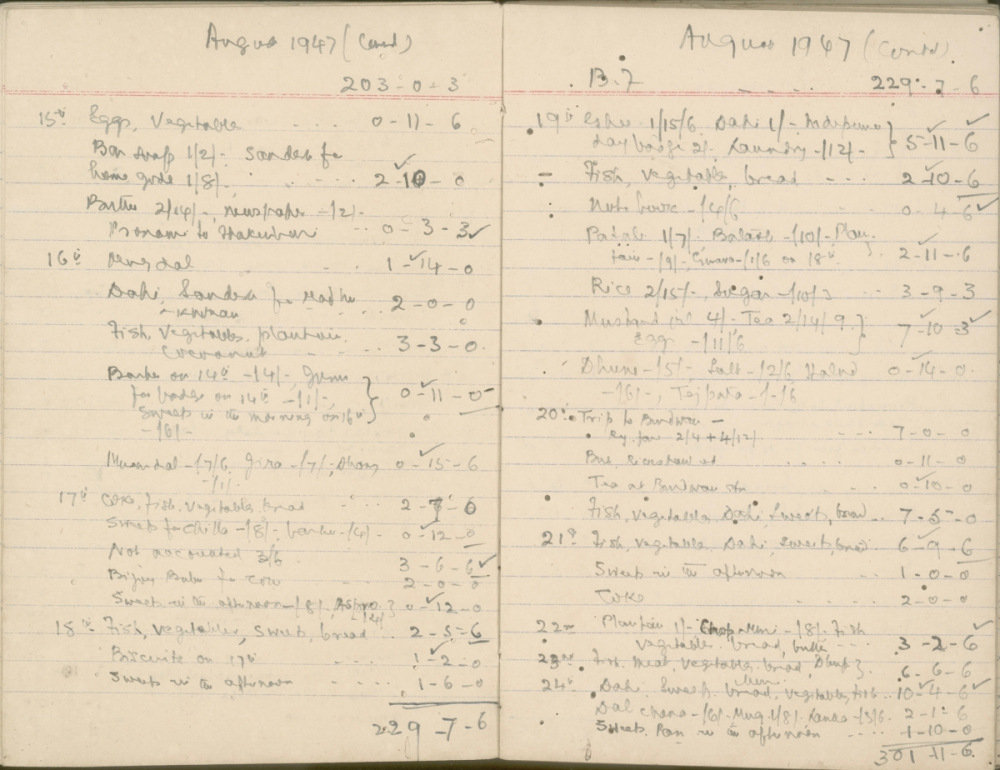

Fig 8: The expenditure diary of Rai Sahib Ashutosh Ghosh (Ghosh: Box 3)

The diaries are interesting in many ways. They detail his expenditure in order— the page above is from the time of India’s Independence in August 1947. Despite the upheaval around him in Calcutta, with large movements of refugees and great violence, his routine changed little. There is no bulk buying, no panic. Every day he goes out and buys a day’s worth of fish, dal and vegetables, a pattern that continued throughout the rest of that year. It shows clearly that Partition affected people very differently.

From a technical point of view, these diaries are also a very good example of the damage that can be done by bookworm. In the image below, you can clearly see the effects of a long-term infestation of worm in the damage that has been done to the pages.

In the past treating this problem would have involved the use of a fumigation chamber. These are expensive, environmentally disastrous and can be dangerous if they are not properly used. Now, when we receive any new archive with signs of worm, mould or silverfish damage, we place it in a zip-lock bag for a year, which kills off damaging infestations. If you have books showing similar signs of damage, this is something that can easily be done at home.

We also hold a small number of ‘commonplace books’. These were quite fashionable at the end of the 19th century, made by young women as diaries of tours overseas. A particularly fine example of this format can be found in the albums made by Millicent Pilkington while she was touring India in 1893–94.

Millicent Pilkington was the niece of the founders of the Pilkington Glass Company—the inventors of the plate-glass manufacturing technique—and the daughter of the Member of Parliament for St. Helens. She went out to India in December 1893 as part of what was called the ‘fishing fleet’: wealthy young women travelling to India in search of a husband from among the very well-off single young men that worked in the country. She didn’t find a husband on this trip, but did keep a very beautifully illustrated account of her travels.

Fig 9: Title page of the Pilkington commonplace book (Pilkington/Phelps: Album 1)

Commonplace books were used to keep accounts of events, and to hold mementoes of the activities being described. The title page for Pilkington’s book is an example of this, with a photograph of Miss Pilkington, illuminated with a watercolour frame and floral border, with the newspaper report of the arrival of her ship at Bombay on the left. If you blow the image up you can see that she has underlined her chaperone Mrs Martin and her name on the ship’s list.

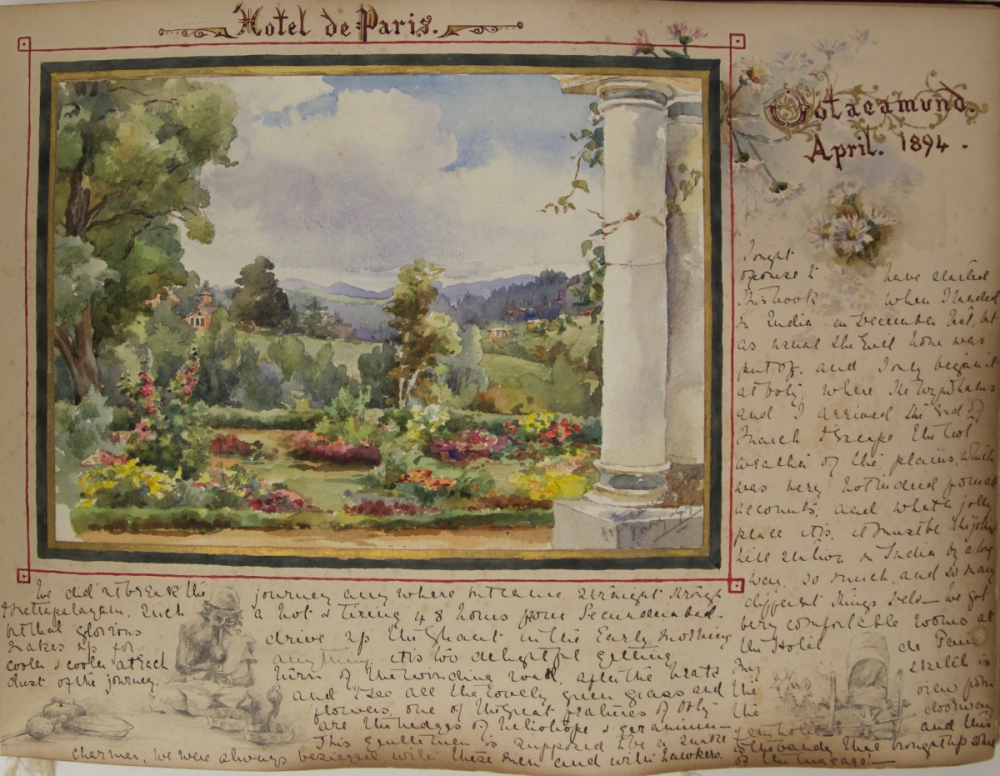

The album goes on to describe her time in very high Indian society, attending balls, parties, plays and other social events. She travels around a little, starting at Ootacamund and going to Wellington, Hyderabad and ‘the jungle’. The next image is from her time at the Hotel de Paris in Ootacamund:

Fig 10: A page from the album of Millicent Pilkington (Pilkington/Phelps: Album 1)

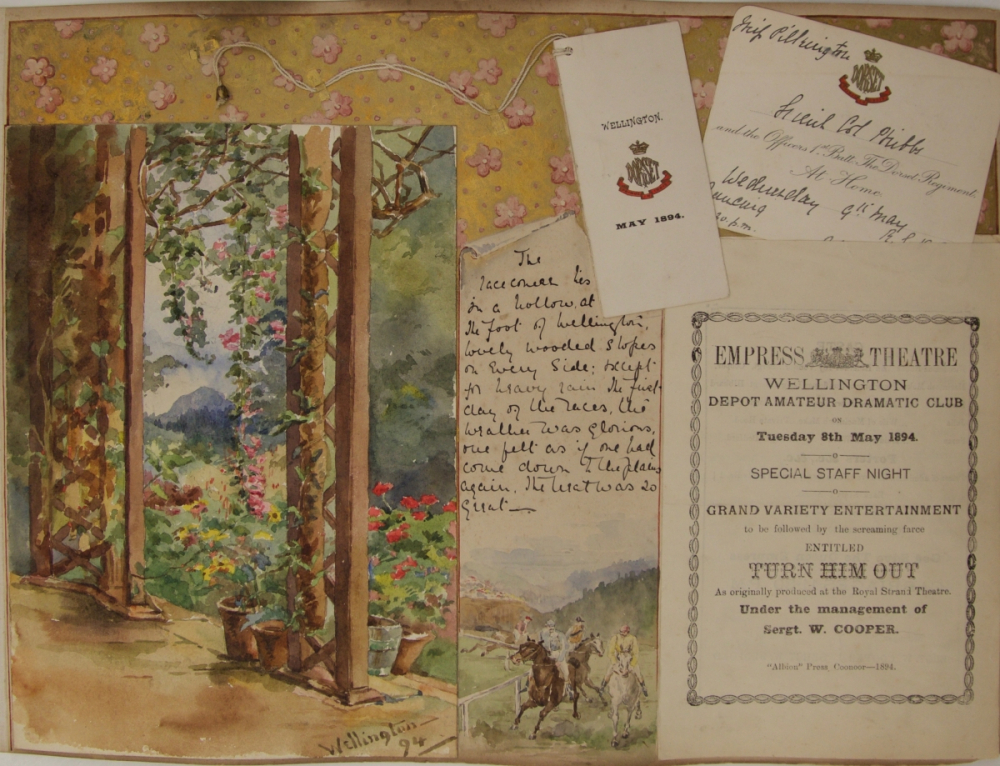

The page facing this one is a perfect example of a typical commonplace book:

Fig 11: Illustrated page from the Pilkington album (Pilkington/Phelps: Album 1)

It has on it a watercolour of the verandah at the hotel, a miniature painting depicting horse racing at Wellington, with a brief description of the races[iii]. The page has an illustrated background in gold paint, and has the programme from a variety performance and a play that followed it. The programme opens out, so you can read what entertainment was laid on for the night. There is also an invitation to an ‘At home’, which promises ‘Dancing’. Next to this is a dance card, which Miss Pilkington would have worn on her wrist at the dances, jotting the names of her partners into it as they invited her to dance. This also opens out, revealing how many of the dances she was asked to join in. Interestingly, at this event, she kept the first and last dances free: a clear indication to all there that she was available to a potential suitor.

One of the most striking features of this beautiful book is the skill and delicacy which she displays when decorating the smaller spaces of the book with tiny ink drawings. For example, the following three images depict a game of golf, an elephant and a polo player. Each of these images is no more than 4 centimetres high.

Fig 12–14: Detail from the Pilkington commonplace book

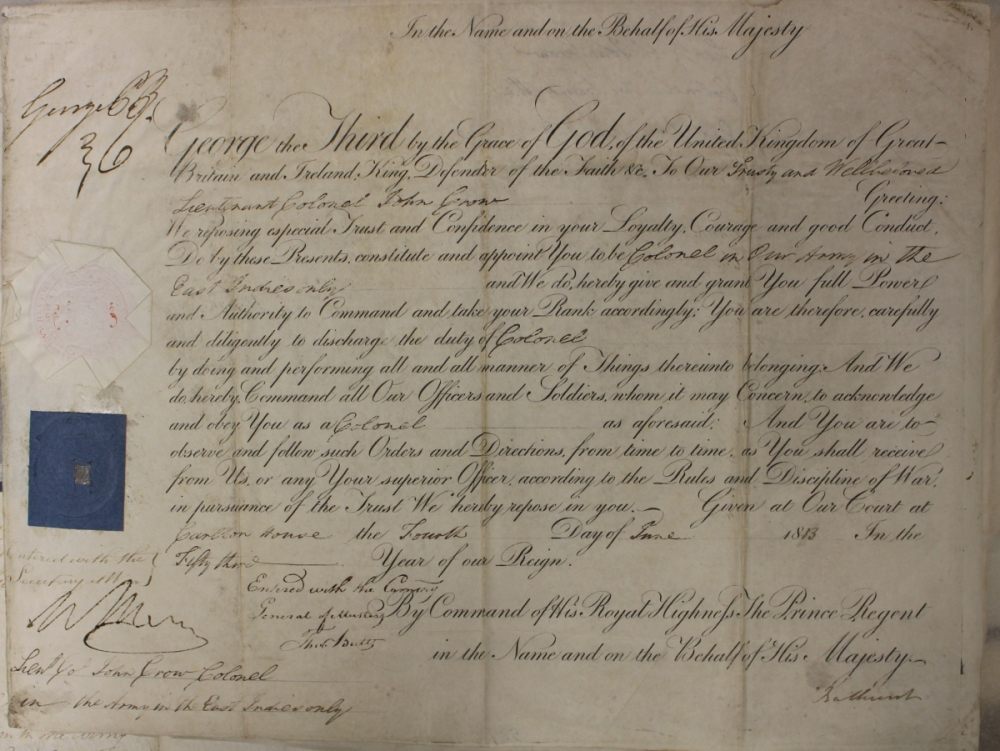

As well as diaries and letters, the Centre’s paper archive also includes official documents, some of which detail the careers of the donors and their families, such as this royal commission promoting Lt. John Crow to the post of colonel. Signed by George III, it is one of a large collection giving full information of the progress of this officer’s career.

Fig 15: Royal commission to the rank of colonel (Crow: Box 1)

We also hold a large number of papers relating to the process resulting in independence for India and Pakistan. Many donors kept newspapers or government missives detailing developments, and many of them were directly involved in negotiations, or in putting down resistance in their part of the country: the Tegart collection, describing the suppression of the Chittagong Rebellion is a good example. Sir Charles Tegart was brought in to the Bengal Police specifically to quash the rebellion, which he did with great vigour. The paper collection is accompanied by a very grisly photograph collection, showing the gruesome aftermath of jungle battles (Tegart: Boxes 1–4, Photo box 52).

2: Photographs

The photographic collection is the least well-catalogued part of the archive. The only full listing of the images is hand-written in pencil. When I became the Archivist, I was told that there were 1,40,000 images in the collection. I doubt this figure—I suspect the real figure is closer to 90,000.

Fig 16: Aerial view of New Delhi, circa 1930

As the video montage in this module shows, there is a vast range in the collection. Similar to the papers collection, the holding is eclectic and varied. Highlights include the Tegart collection mentioned above, images showing the Black Watch, the last British army unit to depart South Asia after Independence, leaving Pakistan. We also have pictures of royal tours, spectacular views of the 1911 Delhi Durbar, rare and detailed images of the building of New Delhi and many domestic and personal collections as well.

The images are being digitised by a team of volunteers from the National Association of Decorative and Fine Arts Societies (NADFAS), soon to be re-named The Arts Society. The process is slow, but we hope to have the first batch of about 15,000 images available on our website during 2018. We are developing a system which will allow images to be added directly to the website as they are digitised, so the number of images should increase gradually after the initial launch.

3: Films

When Mary Thatcher was collecting material for the archive, one of the donors wrote to her saying that he had been going through more of his papers and had come across an old collection of 16mm cinefilms which his father had made during his time in India. He explained in his letter that he did not have the means to play the films, so he had no idea what was in them, nor what condition they were in. He offered the films to Mary, adding that if she did not want them, she should ‘consign them to the flames’.

From this point onwards, Mary began asking new donors if they also had films that they would like to donate. Not surprisingly, given the relative wealth of the British population in India, many of them had owned what was, in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, the latest gadget. A cine camera was an expensive piece of equipment, and the cost of developing the films was even more prohibitive.

They used their cameras to document their lives, to show their workplaces, and also to capture images of what they would have viewed as ‘exotic’ about the country in which they were living. This very orientalist way of recording their lives was not unique to the films: they were very much like the letters that were being sent home as well.

The films were digitised in 1999–2000. We held viewing copies of them on DVD which could be accessed at the Centre. As technology has changed over the last two decades, the way in which we present the films has moved on as well. We believe we were the first repository to put our entire collection of films online and make them freely available. The films on the website are deliberately of poor quality. Keeping them at a low resolution serves two purposes. Firstly, and most importantly, it means that they can be viewed on even the most low-quality internet connection. Secondly, it makes it impossible for them to be used in broadcasts without our knowledge. The archive has no funding at all, so the films are a very important source of revenue: we license their use by documentary makers, which pays for all the activities in the archive.

We do not charge for the use of the material in teaching or academic environments, and will not charge for use in a not-for-profit lecturing setting. If higher resolution copies are required for any such use, please contact the Archivist and arrangement will be made to supply your requirements.

The films cover many aspects of life in British India. The earliest film we hold is from the early 1920s, and the collection continues until the mid-1950s, although recently received films which will soon be added to the website do stretch into the 1960s. The whole collection can be viewed online at http://www.s-asian.cam.ac.uk/archive/films/

The montage film gives a taste of the breadth of the collection. The second film shows our two film collections which deal with Partition. One of them shows refugees arriving in Lahore Cantonment, the other is a collection of films made by the captain of an army rescue team undertaking relief work on the Indian side of the border in Punjab.

4: Audio

In 1974, the Centre’s Committee of Management decided that there was a need to make the archive collections a bit more diverse. Especially in light of trends in Western societies and universities which were portraying Empire as an increasingly negative phenomenon, it was felt that an archive focused so strongly on the Empire which contained very few critical voices was a potential source of embarrassment. It was neither possible nor ethical to collect materials from South Asia, so it was decided instead that an element of balance could be gained by establishing an oral history project in the subcontinent.

An interviewer was employed and the project initiated. Initially, its scope was to collect testimonies about the processes leading to Independence and the early years of independent India. The first interviewer employed was Arun Gandhi, who was very well connected in political circles, and so, in contrast to the rest of the archive collection, the oral history section had at its core material from high-ranking officials, and from those who were at the very centre of the events they describe.

Other interviewers followed, and so the oral history collection has many different areas of focus. There are interviewers with politicians and freedom fighters (from a range of different organisations), with journalists, artists, religious figures, activists, playwrights and actors. It is a fascinating sample of views of the nature of the Independence and nation-building process.

Others have added to this collection in the intervening years: we have Raj Chandavarkar’s interviews with Bombay millworkers, for example. This has given the collection a greater depth and relevance.

Mary Thatcher did not approve of this development, however. She felt that she had been employed to create an archive of the British in India and that this project undermined her mission to do just that. So she established a parallel programme, interviewing more Britons about their time in India.

The resulting collection, therefore, while predominantly South Asian in terms of the interviewees, has a light sprinkling of British subjects as well—quite a few of them people of whom we already have the papers, photographs and films elsewhere in the archive. One very positive aspect of this additional material, though, is that there is an interview with Mary Thatcher herself about the history of the archive and the oral history collection, which is an invaluable piece of institutional history.

In 2004, the whole collection was digitised with aid of a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The work was undertaken with great diligence and technical ability by Mr Ivan Coleby, who had worked at the Centre as a volunteer for a number of years prior to this project. He transferred the interviews to digital files in a number of formats, while creating a database of keywords for each page of transcript. As a result there is a searchable keyword database for the whole collection.

All of the interviews (with the exception of a small number still awaiting transcription) are available on our website (http://www.s-asian.cam.ac.uk/archive/audio/), where the audio file of the interview can be listened to and the transcript read. There are some 300 interviews available on the site which together last approximately 1,200 hours and have just over 10,000 pages of transcripts.

As a bit of a taste of the audio collection, we have an excerpt from an interview with V.B. Gogate, a lawyer and disciple of Savarkar, who gives detailed accounts of the background, the event, and the aftermath of his failed attempt to assassinate Sir Ernest Hotson, 22 July 1931. In this section he describes the assassination attempt itself (the transcript and audio have been edited here from two sections of the interview).

Fig 17: Image of the transcript of the interview with V.B. Gogate

Concluding remarks:

The archive collections of the Centre of South Asian Studies represent a unique and invaluable resource for scholars. This overview has merely scratched the surface of what we hold—there has been no mention of the great number of newspapers, official documents and other resources we are able to offer.

The archive is open to all and there are very few formalities to complete: just fill in the registration form on the library pages of the website (http://www.s-asian.cam.ac.uk/library/register/). Once in the Centre, it only takes a couple of minutes to fetch the papers you want to consult.

For those of you not fortunate enough to be able to visit the Centre in person, there is still a wealth of material available on our website, all of which is free to use. We hope you will find it interesting and useful.

Notes

[i] When it was decided that the Centre also needed an oral history archive, someone had the excellent idea that it would be a good idea to interview Mary Thatcher about the Centre’s archives. This interview is available on the Centre’s website: http://www.s-asian.cam.ac.uk/audio/

[ii] I would like to make a note about references here. Almost all of what I have related up to this point comes from my own knowledge, accumulated from reading the internal filing system at the Centre of South Asian Studies, and from conversations with Mary Thatcher. This article is the first citable source for this information. When I give an example from one of our collections, I will give the collection name and the box number in which it is found. Therefore (Campbell/Metcalfe: Box 1) will refer to Box 1 of the Campbell/Metcalfe collection in the papers, (Thatcher: Interview 1a) will be from Mary Thatcher’s interview, tape 1 side a, (Kendall: Film 3) to the 3rd film in the Kendall film collection.

[iii] The description reads, ‘The racecourse lies in a hollow at the foot of Wellington, lovely wooded slopes on every side; except for heavy rain the first day of the races, the weather was glorious. One felt as if one had come down to the plains again, the heat was so great.’