B.V. Karanth, a name synonymous with Indian repertory theatre, established Rangayana—the first professional repertory in South India. A professional drama repertory with permanent artistes and technicians, Rangayana turns 32 on January 14, 2021. With more than a hundred plays under its banner, it has been spearheaded, after Karanth, by eminent theatre giants: C. Basavalingaiah, Prasanna, Chidambararao Jambe, B. Jayashree, Lingadevaru Halemane, B.V. Rajaram, H. Janardhana, Bhagirathi Bai Kadam, and (presently) Addanda Cariappa. The success of Rangayana is also the result of the government’s support, which has now sponsored branches of the repertory at four corners of the state. Rangayana continues to grow as a dedicated theatre plant, sprouting, as Girish Karnad put it, ‘some of the best plays produced in India’.[1]

Genesis

Vijay Tendulkar describes Karanth as a ‘restless, creative genius’ who always housed a longing for the theatre in his eyes.[2] A 2017 play about his theatre sensibilities is titled Rangajangama (Vagrant of Theatre). Karanth was that: he recognised in theatre a home very early in his life, and ran away from Babukodi, his hometown, to join the Gubbi Veeranna company.[3]

With the fundamental knowledge of folk theatre and music, and aided by Gubbi Veeranna, Karanth pursued an MA (Hindi) and Diploma in Hindustani music at Benaras University. His tidings took him to the National School of Drama (NSD), Delhi, where he graduated in 1962 under Ebrahim Alkazi. Karanth used the rigourous training he had received to teach children at Sardar Patel Vidyalaya in Delhi, only to return to Karnataka after three years. There, he directed (and co-directed with Girish Karnad) stellar works of parallel cinema like Chomana Dudi and Vamsha Vriksha. The first bloom of his theatrical vision remains the troupe he founded with his wife, Prema Karanth—Benaka (Bengaluru Nagara Kalavidaru). His directions of Hayavadana, Sankranti and Jokumaraswamy were critically acclaimed for their innovations.[4]

In 1977, he returned to NSD as director. He was responsible in bringing NSD workshops to non-metro cities in India.[5] While his creativity found an outlet there, administrative responsibilities taxed his brain-force. He accepted the Madhya Pradesh government’s invitation to set up a repertory in Bhopal—Rangamadal. Tendulkar, though, dubs Rangamandal’s productions as mere imitations of Karanth’s earlier productions.[6]

When he returned to Karnataka, the then chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde and his fellows M.P. Prakash and Vittal Murthy—who were ambitious to promote a professional theatre culture in the state—offered a space for the dream Karanth had long fostered in his mind: to guide a group of students into a discipline of theatre.

At Nataka Karnataka Rangayana—the official name of Rangayana in 1989—Karanth did what he did best: dream, train and perform theatre. The 1970s was also a time when contemporary theatre in Karnataka (adhunika rangabhoomi) was undergoing different phases of development. It simultaneously borrowed and strayed from traditional art forms, classical and folk. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, company troupes that only staged mythological narratives interwove social themes into their performances, even as their style remained melodramatic. The royal courts of Mysore patronised many troupes, while villages and tribes had their own touring companies.[7]

From the early twentieth century onwards, the Navya and Navodaya movements (modernist) erupted, combining mysticism, traditional art forms and Western influences that had, in fact, percolated into the lifestyles of the common folk.[8] T.P. Kailasam, educated in Mysore and London, steered a steep turn, using spoken Kannada and realistic set pieces, both a diversion from the grandeur of company prosceniums. His famous plays—Poly Kitty and Tollu Gatti—critiqued with wry humour, and he earned the title ‘Prahasana Prapitamaha’.[9] There was also the influence of Adya Rangacharya (Sriranga). He wrote numerous plays on independence and social revolution, weaving it with everyday life and myths of the community.[10] K. V. Subbanna founded Neenasam in Heggodu and published Sriranga’s translation of Natyashastra. He also set up Tirugata, Neenasam’s performance wing, which, true to its name, performed at different places. This was the background into which Karanth ventured with the idea of Rangayana.

The Foundations

Mysore, the cultural capital of Karnataka, struck the government as a suitable site for Karanth’s theatrical gestation. Moreover, Mysore had a history of theatre. Under the sponsorship of the Wodeyars, who ruled Mysore from 1399 to 1950, several theatre companies had established their nerve centres in Mysore.[11]

Years before the idea of Rangayana, B. V. Karanth had organised a theatre workshop on King Lear for lecturers in a field behind the Kukkarahalli Lake. This was the backyard of the Karnataka Kalamandira, the go-to auditorium for all cultural performances.[12] Although a secondary auditorium had been engineered in the plans, it was never built and it was walled shut as a godown. Discovering this in the layout stone, the founders of Rangayana decided to begin Rangayana there. The wall was demolished, the godown was cleared, and the stretching space became the breeding ground for the repertory.

The functions of Rangayana are divided into three wings today: the professional repertory (including the mini repertory), a training institute, and a documentation centre. This branching happened in 2001. When Rangayana was ideated, Karanth only wanted to begin a full-fledged repertory, first in Mysore, and through its example, in other towns in Karnataka. His experience at Rangamandal had taught him that actors had to thoroughly train before churning out any productions. There, a lack of focused education meant an impoverished team that had no patience to meditate on a production.[13] Here, Karanth rounded up a team of teachers and dramatists, most of them his students—Jayateertha Joshi, C. Basavalingaiah, Raghunandana—to help him build the repertory.

The concept of repertory was new to Mysore, even Karnataka. Indeed, there were many relentless amateur groups like Samudaya and Tirugata, but a repertory was a disciplined space where dedicated members convened every day to hone their skills. S. Ramanatha, a senior artiste at Rangayana, chants the repertory’s eternal law: read a play in the morning, rehearse their incoming production in the afternoon, and perform their present production in the evening.[14]

The Training Period

By the end of 1987, a press notice was circulated to the masses calling interested and experienced youth for auditions. The interviews were conducted in three towns, Mysore, Dharwad and Kondaji in Davanagere, by a panel of noted dramatists—Jayateertha Joshi, Malathi, H. Janardhana—led by Karanth. The audition considered every aspect of an actor—their walk, their diction, their ability to speak different dialects, their training, experience, proficiency in company theatre, knowledge of music and dance, and improvisation techniques. Finally, 19 male artists and six female artistes were selected for training: Arun Sagar, Basavaraj Kodage, Geetha M. S., Hulgappa Kattimani, Jagadish Manavarte, Krishnakumar Narnakaje, M. C. Krishnaprasad, Mahadev, Mandya Ramesh, Mangala, Manjunath Belakere, Mime Ramesh, Nandini K. R., Noor Ahmed Shaikh, Pichalli Srinivas, Pramila Bengre, Prashanth Hiremath, Rangayana Raghu, S. Ramanath, S. Ramu, Santoshkumar Kusanur, Saroja Hegde, B. N. Shashikala, and Vinayak Bhat Hasangi. Jagadish Manavarte, another senior artiste, recalls that a handbook of theatre—Nataka Karnataka Rangakaipidi—was prepared for the auditions, and later went on to become an anthological guide for contemporary theatre in Karnataka. Although a lookout for talent was implicit, the panel relied on the raw energy and undying passion for theatre that these artistes had brought with them.[15]

Rangayana was inaugurated on January 14, 1989. Jagadish Manavarte remembers every line of the song their music teacher, Yoganarasimha, taught them: ‘Sankranthi Sarali Rangakranti’ (May this Sankranthi (the harvest festival celebrated on 14/15 January) bring about a revolution in theatre). This was not simply an ideal taught as a song, Karanth ensured adequate subsistence to prepare for a revolution. He believed that theatre had a distinct voice of its own—it relied on literature, music, dance, theory, etc., but it wasn’t limited by them. Ramanatha suggests: ‘A play isn’t theatre’, meaning that a written play isn’t necessarily theatre, only when refracted through the creative field of the players does the play become theatre.[16] The visual, aural aspects of a performance, the spontaneity of a performance is different from the material, two-dimensional space the play forecloses on paper.

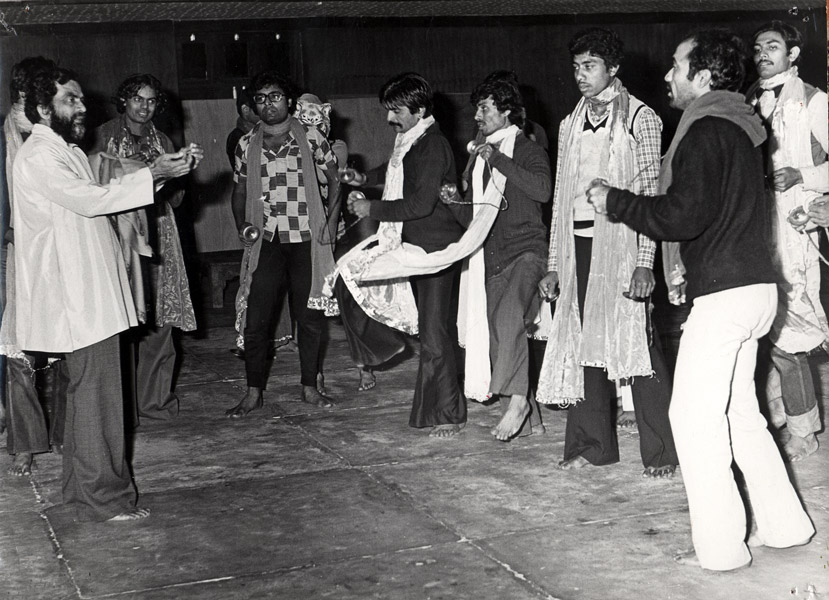

Consequently, Karanth proposed that theatre wasn’t necessarily a written, predetermined play. Manavarte recalls that in the training period the members were taken out of the campus every Monday to observe and experiment in different spaces. He remembers being taken even to a graveyard, where everyone had to create an improvised piece. They had to then write and share their experience. Karanth deemed this informal, experiential training crucial: one had to remain in touch with nature and with society to be able to balance voices and resonate thought in productions.[17]

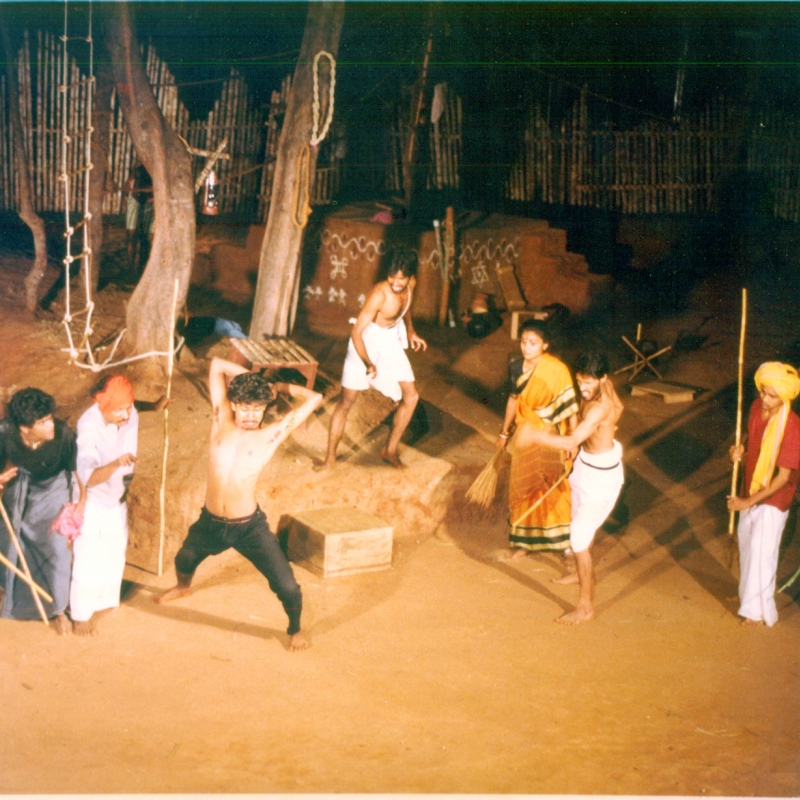

To put together the organising components of theatre, and to acclimatise artistes to the mental frequency of practicing theatre every day, the training extended up to five years. Not only were the artistes trained in acting—by Raghunandana, C. Basavalingaiah, P. Gangadharaswamy, Enagi Nataraj, and Jayateertha Joshi—they also learnt every aspect of a production—blocking, lighting, costume, setting, designing (H.K. Dwarkanath from Rangayana is one of the most qualified set designers of India), and directing. Manavarte speaks about another challenge Karanth would throw at them: memorising entire plays, including stage directions. ‘We presented—singularly—plays like Samsara Birudentembara Ganda and Gandasu Katri,’ he beams.[18] Apart from this, they were trained in music—by H. K. Yoganarasimha, Karanth, Bhushan, and, later, Srinivas Bhat (Cheeni); in yoga—by Shankaranarayana Jois; in martial arts—by Anju Singh.

When asked whether general fitness necessitated martial arts, Anju Singh disagrees, and describes the reason behind this training. ‘Take a play like Romeo and Juliet,’ he begins. These plays have duel sequences, and so do Indian mythological plays. Sometimes, there are stunt sequences. Without training in martial arts, verisimilitude seldom takes place. ‘Especially in the age of TV and cinema, where stunts are greatly detailed, theatre also begs truer performances. We’re the equivalent of stunt directors,’ he adds.[19] It was a hard but fruitful journey for Anju Singh, a martial-arts specialist. He had to learn the ways of adapting his skill for theatre, along with the artistes. Every teacher at Rangayana grew as much as the artistes.

Apart from the permanent faculty, Karanth invited eminent directors from both India and abroad for workshops such as John Martin, Vashilios Kalitsys, Kamsale Mahadevaiah, Iliana Citaritsi, to name a few.

The Curtains Rise

At Rangayana theatre is a community activity. The audience is as important as the artiste. So, not only were there staged productions in the very first year, even their training was presented to the crowd. Shantamudre was a yoga performance. Veera Varase Samarakale used a combination of martial arts. These performances came under purvaranga, literally ‘before the stage is set’. There were ten purvaranga shows. Govina Hadu was a stage rendition of a Kannada folk song about a cow Punyakoti’s honesty. This first production faced two challenges—portraying animals and staging a song. But the exercise proved beneficial to the artistes and crew, since they explored difference ways of staging songs. The actors did not merely sing songs but translated them visually on the stage. Kindari Jogi, a song by Kuvempu after Pied Piper, was the next show. For this performance, the Vanaranga stage, first used by Karanth for King Lear, was remade to create the atmosphere of an amphitheatre. A year later the troupe played Tirukana Kanasu, based G. P. Rajaratnam’s song of the same name.

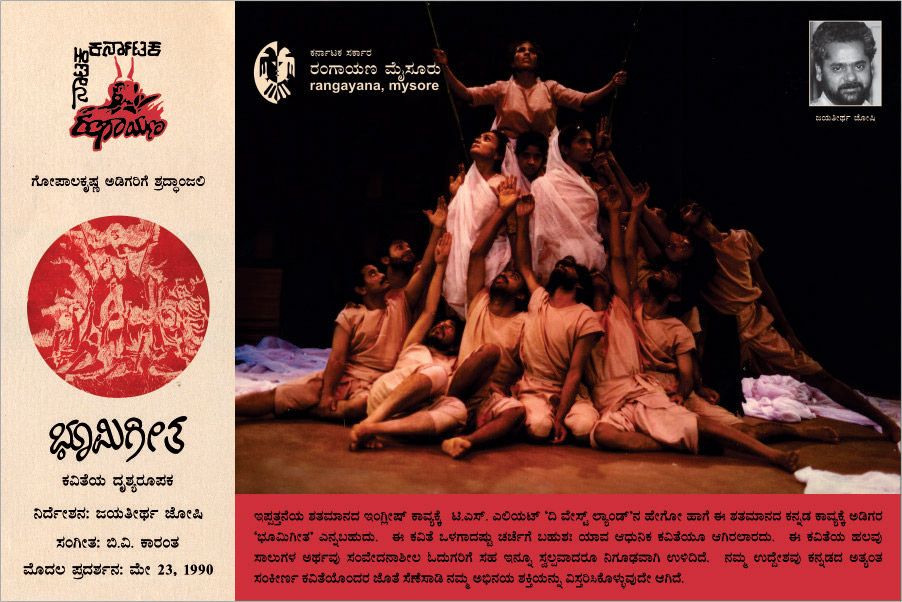

The zenith of song adaptations was Jayateertha Joshi’s experimental production Bhoomigeeta (May 1990). This poem by Gopalakrishna Adiga is a cultural adaptation of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. While Govina Hadu, Kindari Jogi, etc., were all narrative poetry, Bhoomigeeta is a thought—the song of the earth, it’s lamentation at human unproductivity—distilled in poetic images. The poem does not move in time. How, then, can it be staged? Ramanatha says that it was developed during the training sessions, in a span of eight months. The artistes selected four to eight lines in a session and improvised it on stage. No protagonists, no characters, no sets. A coming together of actors and their skills to produce rich visuals that supplemented the poem recital in the background. He explains one line from the poem: ‘Tottilangadiyalli bombu tumba hagga,’ which hints at the discovery of birth in death, and vice-versa.[20] This one-and-a-half-hour production dispelled the popular notions of theatre as a performative narrative based in a story. So acclaimed was Bhoomigeeta that it lends its name to the main theatre of Rangayana today. The weekend productions of Rangayana continue to be performed at Bhoomigeeta.

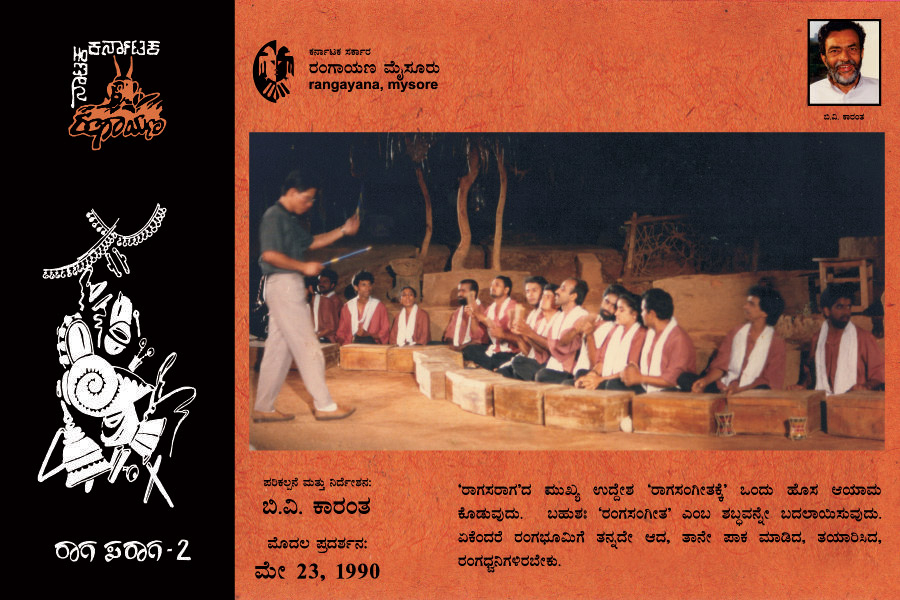

Karanth’s theatre was musical. He was responsible for inculcating music on the stage organically rather than as interventions.[21] In Rangayana, he extended the meaning of music from the supplementary to the natural. Some of the purvarangas were episodes of this experiment, such as Raga Saraga performances—an exploration of the sound of theatre, the rhythm of its world. The artistes examined the voice, the beat, the note, the noise, chaos, tempo, all with coconut shells, stones, soil, bamboo, etc.[22] These performances were also presented to audiences in Delhi and Bombay.

In their second year, Vashilios Kalitsys was sought to direct Euripides’ Hippolytus. A Greek play with Greek music, the play was transported to an Indian context, thus necessitating Kannada songs. Although this show was received much applause abroad, at New York and Germany, it was most exciting in the Rangayana premises. In adherence to Karanth’s vision of ‘bayale rangamandira’, open fields became performing spaces. One cannot miss the excitement in Manavarte’s eyes as he recounts the play: ‘The hunters would run from two furlongs away through the path adjoining Kukkarahalli Lake. The Goddess descended on a ramp from the trees further inside the campus. Fire-torches flanked the path through which characters appeared. It was Greece, but it was also India.’[23]

One can feel a similar energy when artistes peak about Belekalina Prasanga. The storyline aside, this was the first experiment in Karnataka that primarily dealt with masks. Not only were huge masks prepared and used in the production, but it simultaneously thought about the aesthetic, technical and philosophical meaning behind the usage of masks: did masks hide or reveal, add or delete?[24] The lawns of the campus were moved to create a temporary hillock on which the artistes climbed, first revealing their giant masks to imprint an exaggerated character in the imagination of their audience.

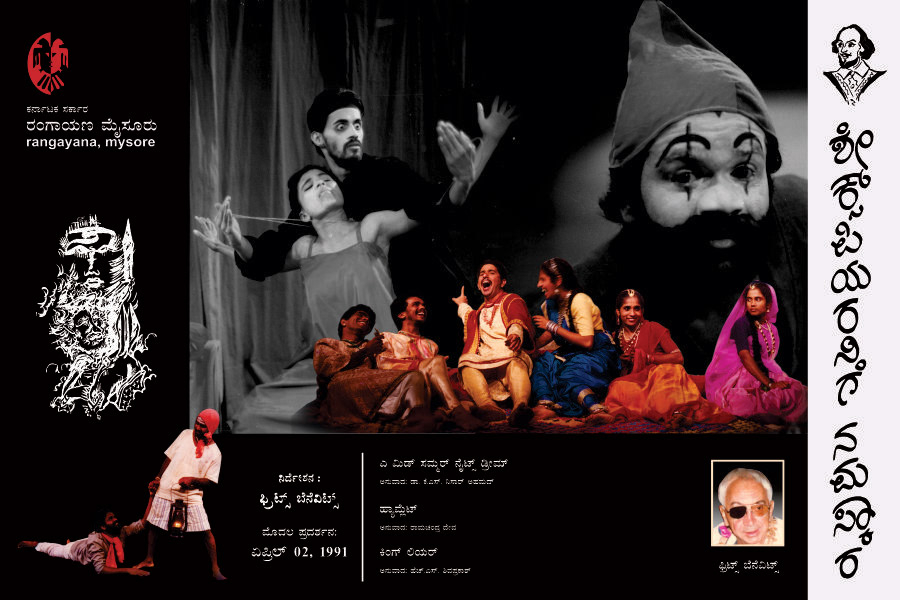

Rangayana also hosted Fritz Bennewitz. The East-German Brechtian first directed a collage of Shakespearean plays Shakespearege Namaskara in April 1991, thus initiating the artistes to Shakespeare. An exacting and dedicated director, he later came back in December 1991 to commit to another playwright from another era and location: Chekhov. The Cherry Orchard was staged to the Mysore audience on December 28, 1991. In testimonials printed in the brochures, the artistes write about the deep influence Bennewitz had on them. ‘He had no knowledge of Kannada. But he knew the language of theatre—and he’d spot our flaws, even in our pronunciation,’ Ramanatha says.[25] Indeed, his contribution has impacted not only Rangayana but the face of Indian theatre itself.[26]

Bennewitz was impressed with the institution. In his own words, working in Rangayana was ‘dare-devilish mountaineering – and the training camp [was] in the steep slopes of the Himalayas of Drama.’[27] His friend Rustom Barucha was skeptical about The Cherry Orchard production. Expressing his concern, he informed Bennewitz in a letter that Chekhov was a test to Indian performers who weren’t trained to work from within.[28] But the artistes proved that Chekhov was as close to them as a Kalidasa or a Kuvempu. Rangayana had found the spiritual experience of acting that Barucha was searching for in Indian theatre circles.

In 1995, Barucha himself landed in Rangayana to direct Gundegowdana Charitre, an adaptation of Peer Gynt. This lengthy Danish play by Henrik Ibsen is a blend of Norwegian folklore, legend and realism. It was adapted to Kannada by Raghunandana, who translocated the entire play into Karnataka. Since the Norwegian source texts were not accessible, they had to consult multiple English translated texts: this allowed an adaptation from ‘more than one English to more than one Kannada.’[29] ‘God, the Father’ and ‘Saint Peter’ became Maleya Mahadeshwara Madanna and Basavanna—folk deities of the Mysore culture; ‘Solveig’ became the Tulu-speaking Gulabi. The production was an exploration of intercultural and intracultural negotiations of theatrical adaptations.[30] This academic approach to theatre, harmonious with artistic sensibilities, is the hallmark of Rangayana. Their performance remains to be, as of 1996, the only adaptation of Peer Gynt in an Indian language.

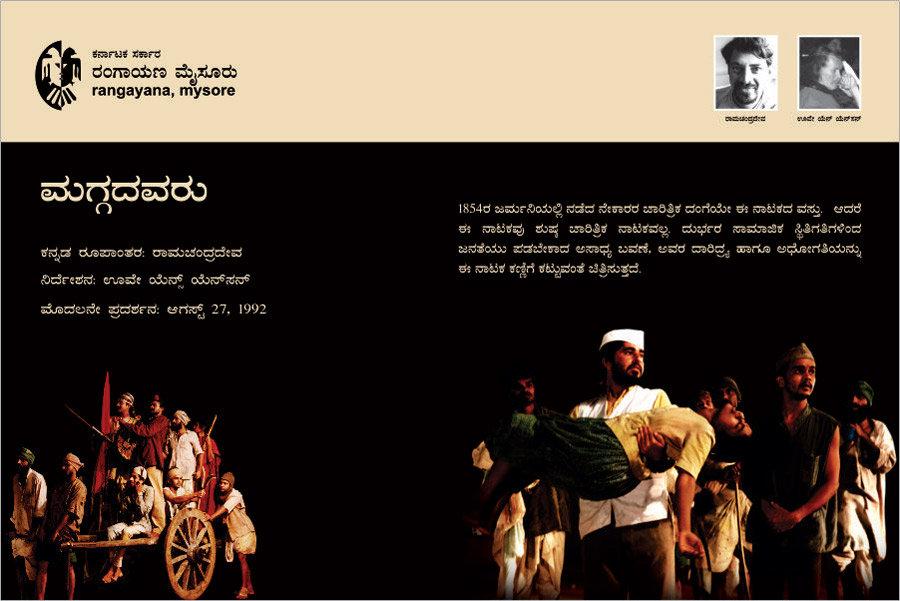

Another cross-cultural adaptation at Rangayana was a collaboration with the Max Mueller Bhavan for the play Maggadavaru, in 1992. Originally The Weavers by Gerhart Haupmann, the play chronicles the life and uprising of weavers in Germany in 1845. The directors—Uwe Jens Jensen and Heide Brambach—considered the Indian adaptation important since it was a reflection of a class of society being oppressed under structures of social life.[31]

For Maggadavaru, the cast and crew decided to change the spatial positions of actors and audience: the audience sat in the middle with the stage all around them. The intention was to have a stage on all four sides of the audience, one stage connected to the other. The play on weavers was thus woven around the audience, to give a sense of locational change from scene to scene.

Karanth was never an advocate of the proscenium. Manavarte, speaking about the informal training sessions, recalls how his mentor was never keen on having a permanent stage. ‘Bayale satya’ was Karanth’s phrase: the truth is in the open field. Bhoomigeeta and Vanaranga referred to locations more than completely built stages. Since there were no periodical performances to put up, the stage was designed differently for each play. Elevated platforms were built, chairs arranged as it suited, slotted angles placed differently. Bhoomigeeta was a thotti mane—lending itself to be altered as required. Once set, the set would remain until the play closed. For A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by German director Christian Stuckl in 1994, the entrance of the present Bhoomigeeta became the dais, the audience facing the opposite direction. While that explains why the repertory did not outline a permanent setting for their performances well until 2002, Manavarte or Ramanatha do not consider the lack of infrastructure a liability. ‘Every production was a festival to Karanth. In each house, the festival is different. Each year, it’s different. Each production is different,’ Manavarte says.[32] His lines find resonance with the general ethos of Karanth’s theatre: ‘less famous for design…but for colour, music, dance, narrative and intellectual content’. The constructed stage didn’t matter since his was ‘total theatre…infused with joie de vivre.’[33]

These experiments with form have been complemented by the wide range of themes Rangayana has touched. Raghunandana wrote and directed, in 1993, Etta Haride Hamsa, which inspected the paucity of Gandhivada in the society. Raghunandana asks if we are now a world without values, and Gandhi just an effigy for veneration.[34] This isn’t the stance of the repertory. Rangayana’s ideology is fine theatre. Their activity ends in generating a dialogue; meaning is for the audience to construe. Years later, in 1998, the same troupe performed Ajit Dalawi’s Gandhi vs. Gandhi, which investigated the ideals of truth and honesty espoused by Gandhi by delving into Gandhi’s relationship with his son.

In 1993, after directing Sriranga’s Kattale Belaku, Karanth felt the need to organise a seminar on Sriranga. True to his name, Adya Rangacharya, Sriranga is considered the ‘first teacher of theatre,’ for having translated the Natyashastra into Kannada, and forever probing the meaning of theatre.[35] Indian theatre circles were well-versed with Sriranga’s works since translations of his plays were available. In September 1993, from 24 to 26, a formal podium was set up under Sriranga Namana Natakotasava. Playwrights and theatre scholars from all over India were invited: Mohan Maharshi graced the occasion too. The highlight of this festival was Swagata Sambhashane, performed by Karanth himself. Rangayana has harkened to Sriranga once again in 2008, when Kelu Janamejaya was directed by Ramanatha.

As director, the last play Karanth prepared was Chandrahasa. Written by Kuvempu, the play traverses orthodox religion and its offspring—the caste system—together with the spiritual endeavour of the Bhakti tradition. The narration has to do with Chandrahasa, the emperor of Kuntala from Mahabharata. Although the production was heavily based on Kuvempu’s play, Karanth’s influences included Jaimini Bharata by Lakshmeesha and countless Yakshagana performances.[36]

Karanth Leaves, his Dream Continues

The repertory remained an orphan with the sustenance of one play, Siri Sampige, when Karanth left Rangayana in 1995, stating health reasons. Government funding was draining, and there was even a point of time when the government suggested complete dismantling.[37] Due to efforts by writers and playwrights, led by Girish Karnad and Devanur Mahadevappa, the repertory survived. They demanded conceptual and financial autonomy for the institution. C. Basavalingaiah, Karanth’s student and the troupe’s mentor, finally took over as director.

During this time, events led to the formation of Rangasamaja—the executive administrative body of Rangayana. The Minister of Kannada and Culture de facto chairs the body, with fourteen other members. Rangasamaja is a body that deliberates between the government and the repertory, treading the balance between artistic autonomy, financial support and practical constraints.[38]

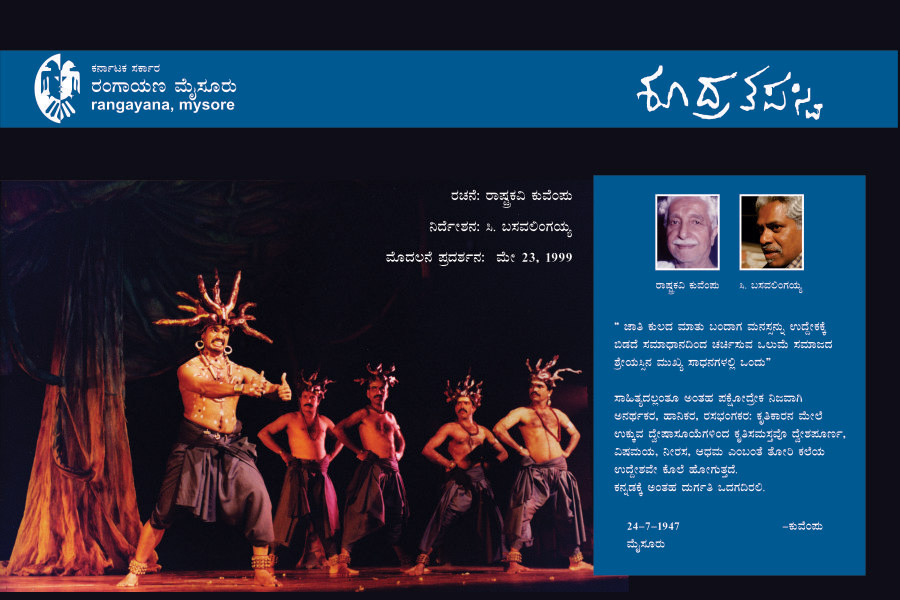

Within a year, Basavalingaiah brought Karanth back to the institution to direct a classical play: Kalidasa’s Agnivarna in Kannada. Basavalingaiah himself directed Gandhi vs. Gandhi, Tippuvina Kanasugalu, and Shudra Tapaswi. Shudra Tapaswi was critically acclaimed literature, since it brought to focus a passing character of Ramayana—Shambuka, a shudra ascetic. In the Sanskrit version, Rama slays Shambuka because shudras should not perform ascetic duties, while in Kuvempu’s version, Rama chooses to protect him, and the play indirectly critiques the system of caste oppression. But it was the first time the play was designed, directed and performed—well enough to inspire more performances.

Ramanatha extends the point to claim that Kuvempu was a widely read playwright, but it was Rangayana that unveiled the performability of his plays.[39] Rangayana’s invocation of Kuvempu time and again—from Kindari Jogi, Chandrahasa, Shudra Tapaswi, Malegalalli Madhumagalu to their magnum opus Sri Ramayana Darshanam has immortalised the giant of Kannada literature on stage.

New Beginnings: Turn of the Century

Prasanna was appointed as director in 2001 after Basavalingaiah retired. Having immense experience with the theatre repertory Samudaya, Prasanna came to Rangayana with a vision. Although his tenure lasted only two years, his contribution is second to Karanth in expanding the scope of the institution. Apart from directing Pugalendi Prahasana, an inventive adaptation of The Servant of Two Masters, Prasanna was determined to plug the holes in the logistics and organisation of the repertory, which he deemed as important.

Although Prasanna’s inspiration to theatre was Karanth and his madness, his style was a departure from his teacher. It was important, Prasanna believed, to have a permanent stage to ensure regular performances. Having to build a stage for every production also meant that productions could not be repeated as and when required. Assisted by the central and state governments, Prasanna proposed the renovation of Bhoomigeeta and Vanaranga. He also set up a new auditorium, Sriranga, for rehearsals, one-man shows and seminars. All these spaces were designed by architect Dr Shashibhushan, and were ready by the end of 2011.[40]

With a permanent theatre to house public, Prasanna ratified the varantya pradarshanas or the weekend performances, a tradition that had travelled unbroken until the pandemic broke out in 2020. Initially on every Saturday and Sunday, and currently only on Sundays, the repertory presents a play at Bhoomigeeta.[41] Whenever the repertory is unable to come onstage, other troupes are invited to present their play in this slot. Unique to Rangayana, a production every weekend led to better engagement with the community. To compensate for this loss during the pandemic, Rangayana produced YouTube play readings from Bhoomigeeta.

Prasanna also established the Bharathiya Ranga Shikshana Kendra, a national-level theatre school that offers a year-long diploma course with a stipend for 25 selected students.[42] The training aims to cover every facet of theatre as Karanth envisioned it, and as Rangayana artistes have themselves visualised. Students are trained in music, dance, martial arts, acting, directing and theory, with the opportunity to produce an annual performance. Some of these students are also offered to join the mini repertory, the secondary troupe of Rangayana, whose members are taken on a contractual basis. Apart from the artistes themselves, teachers and resource people are also inducted from outside the institution.

Prasanna channelled the documentation centre that housed literature, plays, scripts and archives of the institution, and named it Sriranga Ranga Mahiti Samshodhana Kendra. In this well-equipped library, one can explore the entire trajectory of Rangayana.

The inauguration of Bhoomigeeta happened during the first national-level theatre festival, Akka, from November 18 to 25, 2001. A tribute to the spirit of Indian womanhood, the festival included plays, seminars, street theatre and photo exhibitions. The term akka was chosen because it is a term of addressal, even though it immediately refers to the elder sister. Akka also echoes the persona of Akkamahadevi, a twelfth-century vachana poet who wrote unabashedly about social reform and practiced her preach.[43] Bhagirathi Bai Kadam was invited to direct Sarasammana Samadhi for the repertory; the mini repertory visualised vachanas of Mahadevi on stage; troupes from all over India were hosted to perform their shows.

Following the success of Akka, Rangayana hosted another national-level theatre festival, Bahuroopi, with the theme of social justice in mind. Named after Bahuroopi Chowdiah, a contemporary of Basavanna, the festival focused on ‘marginalisation and [the way] social abberations could be corrected through theatre.’[44] There were various troupes from all over India performing in different languages and theatrical forms. One of the aims, for Prasanna, was to put folk theatre and contemporary theatre on the same pedestal, since he believed that folk theatre developed as organically, and was mostly the voice of the ‘have-nots.’ Bahuroopi also means ‘multiple forms’, illustrating the diversity of the festival: Kavyabhinaya of Bahuroopi, directed by Mudnakudu Chinnaswamy, performed by Rangayana; seminars on folk narratives and modern theatre in collaboration with Central Institute for Indian Langauges (CIIL); Rajasthani folk, Burra Katha, and Kalaripayattu; film screenings, book exhibitions, and a photography expo.

These two festivals prompted Rangayana to consider an annual national theatre festival. Held every year in December–January, the fest continues to be called Bahuroopi, and deals with a different theme every year: children’s theatre, desi culture, agriculture, Shakespeare, migration, etc.[45]

The Decade of Innovation

During the decade 2001–2010, under the stewardship of Prasanna, Chidambararao Jambe (2004–08), B. Jayashree (2009), and Lingadevaru Halemane (2010–11), Rangayana produced eclectic plays: Katharanga recorded four partition stories by Manto, Ibne Insha, Lalithambika, and Duggal. R. Nagesh directed Krishnegowdana Ane, based on Poornachandra Tejaswi’s story—the task of the artistes here was to persuade the audience on the physically non-existent elephant on the stage. Comedies rolled in: there was Heegondu Pranaya Prasanga in 2004; Beechi Bullets based on Beechi’s work in 2006. Contemporary playwrights were also given their due: Vijay Tendulkar’s Saddu Vicharane Nadeyuttide, a meta-drama exposing the hypocrisy of patriarchy and foeticide, was directed by Manjunath Belakere; Lankesh’s Police Iddare Eccharike was directed by Jagadish Manavarte; and Mahesh Elkunchwar’s Chirebandi Wade directed by Pramila Bengre. The play was so celebrated by the audience that Prashanth Hiremath and Nandini K. R. went on to translate to Kannada the entire trilogy. Shakespeare found a stage again: Prasanna returned to direct Hamlet; Jambe directed O... Lear, which began with madmen on stage—the essence of the play was the madness in all of us.

In 2010, Rangayana pursued a herculean task: to stage Kuvempu’s 750-page novel Malegalalli Madumagalu. This had been Karanth’s dream project: to present a nine-hour play on an expansive novel. Malegalalli Madumagalu is not plot-driven. There are no dramatic conflicts, no protagonists, but it is a magnificent cultural document of a village, their lives and lifestyle, amidst which a lad wants to marry through mischief. Using K. Y. Narayanaswamy’s adaptation, the artistes, from Rangayana and outside, worked by improvisation again, on four different stages designed by the director Basavalingaiah and H. K. Dwarkanath. Ramanatha recalls: ‘Basavalingaiah is a great scenic designer. He said there shouldn’t be constraints of a single stage. We moved from the doors of the campus to the pitch behind Kukkarahalli Lake and so on. Began at nine in the night, and performed upto five in the morning. It was a break from convention…’[46] This remains a grand success of Rangayana—every show summoning more people, from as far as Bidar and Gulbarga.

Recent Years: Post 2011

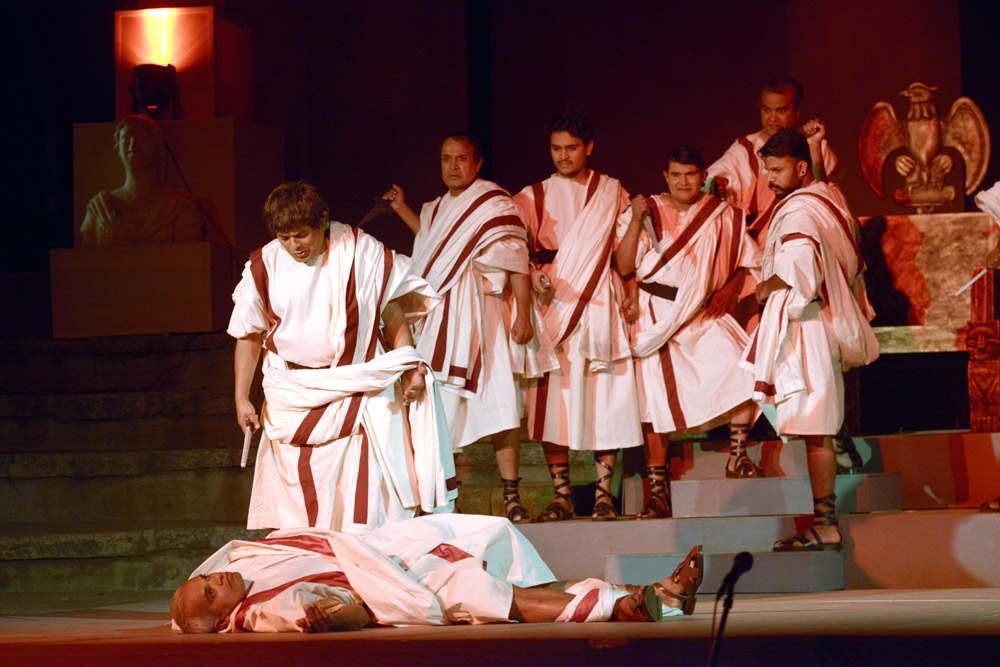

Rangayana revived Sadarama Natakam, the famed company musical, under the helm of Y.M. Puttannayya from the Gubbi Company. As director of the institute, B.V. Rajaram directed an adaptation of Chandrashekhar Kambar’s novel Shikharasurya. The same trend followed when H. Janardhana, in 2015, directed U. R. Ananthamurthy’s novel Samskara, changing the actors midway to portray the transformation in Praneshacharya. In 2017, another novel was staged, Shikari by Yashwanth Chittal. Prakash Belawadi brought alive not only the cacophony of Mumbai on stage but also the cacophony of the mind—the conflict of being a prisoner of the selfish interests of others. Shakespeare made his presence again with Julius Caesar—for which the setting of Vanaranga was inverted. The steps of the amphitheatre became the Roman galleries, and on the dais sat the audience. G.K. Govindarao, Kannada professor and dramatist, directed the play.

2018 was a year of ups. Along with Chekhov’s Moovaru Akka Tangiyaru and a revival of Chirebandi Wade, the repertory presented another company play under Y.M. Puttannayya—Giribhatta Tammayya’s Manmatha Vijaya. The last play was a commercial success, filling every seat and more from the end of July until December 2018.[47] In parallel, Rangayana began its taleem on Sri Ramayana Darshanam, the epic work that earned Kuvempu the Jnanapitha award. The play was a grand success all over Karnataka, and its focus on Manthara, Sugriva, Ravana and Maricha received critical attention.[48] In 2019, Rangayana staged its first all-women play The House of Bernarda Alba under Bhagirathi Bai Kadam’s direction, along with a folkish fable, Pushpa Parijata.[49]

Other Activities

In sync with Karanth’s vision, branches of Rangayana have been set up in Shimoga, Dharwad and Kalburgi. Talks of another branch is underway.

Besides its productions and training, Rangayana is involved in a lot of activities to bridge gap between the theatre community and the public, the professional and the amateur. Chinnara Mela is held every year in the summer for children. Rangayana artistes organise workshops to develop a child’s interest in theatre. Each child is a part of a performance at the end of the programme. A collection of poems, penned by the children, is published by the institution. When it was initiated by Basavalingaiah, it was confined to the campus in Mysore.[50] With each director the scope has expanded. Under Bhagirathi Bai Kadam, the summer camp was organised in villages with a mid-day-meal scheme.

While the artistes go on a month-long vacation, amateur troupes are invited to perform for the weekend performances. This happens during the spring and is called the Greeshma Rangotsava. Similar fests happen during Dasara, where performances are sponsored on every day of Navaratri. In the B.V. Karanth College Rangotsava, Rangayana artistes and technicians direct plays for interested college students.

Legacy

Rangayana has created a benchmark for quality theatre in India. People who have closely worked with Rangayana have voiced praise on the discipline and dedication of the repertory, despite the many odds they have had to face in building the institution. In fact, when Rangashanakara was inaugurated in Bangalore, Rangayana was invited to perform Mayaseeta Prasanga as the invocation. Rangayana has influenced a number of amateur troupes to strive for professionalism in their work. Some artistes have branched out of Rangayana, while some have expanded their base: Mandya Ramesh has begun a theatre institute in Mysore called Natana; Mime Ramesh also set up his own troupe GPIER; Ramanatha is a well-known scholar and playwright, with plays like Carbon Cake, Pugalendi Prahasana to his credit; Prashanth and Nandini advise the Rangavalli troupe in Mysore, directing and designing plays; Pramila Bengre and Hulgappa Kattimani work with jail inmates and produce theatre. Each artiste is a tall resource person, an asset of the Kannada theatre world. But most importantly, Rangayana’s forte has been in experimenting and succeeding each time—be it Bhoomigeeta or Malegalalli Madumagalu, Rangayana has worked, in the era of the television and cinema, out of the box, redrawing the boundaries of theatre time and again. Rangayana has sketched the infinite possibilities of theatre: expression and catharsis, justice and provocation, education and entertainment.

Notes

[1] Rangayana. Reports on Bahuroopi 2018.

[2] Tendulkar, ‘The Genius of Karnath.’

[3] Riti, ‘End of an Era.’

[4] Menon, ‘A Genius of Theatre.’

[5] Riti, ‘End of an Era.’

[6] Rangayana, Reports on Bahuroopi 2018.

[7] Swamy, ‘Actor Training: Contexts, Methods and Practices in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.’

[8] Shivaprakash, ‘The Evolution of Modern Indian Theatre.’

[9] The Hindu. ‘Kannada’s Only Kailasam.’

[10] Shivaprakash, ‘The Evolution of Modern Indian Theatre.’

[11] Swamy, ‘Actor Training: Contexts, Methods and Practices in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.’

[12] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

[13] Tendulkar, ‘The Genius of Karnath.’

[14] Ramanatha S. in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[15] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

[16] Ramanatha in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[17] Manavarte in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[18] Manavarte in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[19] Singh in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[20] Ramanatha, in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[21] Tendulkar, ‘The Genius of Karnath.’

[22] Rangayana, Raga Saraga.

[23] Manavarte in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[24] Rangayana, Cherry Thota and Belekalina Prasanga.

[25] Ramanatha in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[26] Esleben, ‘The Late 1980s and Early 1990s.’

[27] Rangayana, Cherry Thota and Belekalina Prasanga.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Barucha, ‘Under the Sign of the Onion: Intracultural Negotiations in Theatre.’

[30] Ibid.

[31] Rangayana. Maggadavaru.

[32] Manavarte in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[33] Menon, ‘A Genius of Theatre.’

[34] Rangayana, Etta Haride Hamsa.

[35] Rangayana, Kelu Janamejaya.

[36] Rangayana, Chandrahasa.

[37] Davis, ‘Karnataka's state theatre repertory staggers towards closure due to lack of Govt support.’

[38] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

[39] Ramanatha in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[40] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

[41] The Hindu, ‘Weekend theatre will be one-day affair.’

[42] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

[43] Mehu, ‘Akkas thangis invited to Rangayana’s theatre festival.’

[44] Naganna, ‘A Festival of Multiple Forms.’

[45] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

[46] Ramanatha in conversation with Vighnesh Hampapura.

[47] Hampapura, ‘The Vijaya is Rangayana’s.’

[48] The Hindu, ‘Kuvempu’s ‘Ramayana Darshanam’ is now a play.’

[49] Star of Mysore, ‘Rangayana To Stage ‘The House Of Bernarda Alba’ From July 21.’

[50] Rangayana, A Brief Introduction to Rangayana.

Bibliography

Barucha, Rustom. ‘Under the Sign of the Onion: Intracultural Negotiations in Theatre.’ New Theatre Quarterly 12 (46): 116–28.

Davis, Stephen. ‘Karnataka's state theatre repertory staggers towards closure due to lack of Govt support.’ India Today, Noida, February 29 1996. Accessed July 30, 2018. https://www.indiatoday.in/magazine/indiascope/story/19960229-karnatakas-state-theatre-repertory-staggers-towards-closure-due-to-lack-of-govt-support-835183-1996-02-29.

Esleben, Joerg. ‘The Late 1980s and Early 1990s.’ In Fritz Bennewitz in India: Intercultural Theatre with Brecht and Shakespeare, 224–26. London: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

Hampapura, Vighnesh. ‘The Vijaya is Rangayana’s.’ Star of Mysore, Mysore, August 31 2018. Accessed September 3, 2018. https://starofmysore.com/the-vijaya-is-rangayanas/https://starofmysore.com/the-vijaya-is-rangayanas/.

Mehu, Sowmya Aji. ‘Akkas thangis invited to Rangayana’s theatre festival.’ Times of India, Bangalore, October 11, 2001. Accessed July 23, 2018. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/Akkas-thangis-invited-to-Rangayanas-theatre-festival/articleshow/1161849327.cms.

Menon, Parvathi. ‘A Genius of Theatre.’ Frontline 19 (20), New Delhi, October 12–25 2002. Accesssed August 8, 2018. https://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl1920/stories/20021011005912100.htm.

Naganna, C. ‘A Festival of Multiple Forms.’ Frontline 20 (04), New Delhi, February 15–18 2003. Accessed July 23, 2018. https://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2004/stories/20030228002108200.htm.

Rangayana. Raga Saraga. Mysore: Rangayana, 1990.

Rangayana. Cherry Thota and Belekalina Prasanga. Mysore: Rangayana, 1991.

Rangayana. Maggadavaru. Mysore: Rangayana, 1992.

Rangayana. Etta Haride Hamsa. Mysore: Rangayana, 1993.

Rangayana. Chandrahasa. Mysore: Rangayana, 1994.

Rangayana. Kelu Janamejaya. Mysore: Rangayana.

Rangayana. A Brief Introduction to Rangayana. Mysore: Rangayana, 2013.

Rangayana. Reports on Bahuroopi 2018. Mysore: Rangayana, 2018.

Riti, M. D. ‘End of an Era.’ Rediff News, 2002. Accessed August 8, 2018. http://www.rediff.com/news/2002/sep/03spec.htm.

Shivaprakash, H S. ‘The Evolution of Modern Indian Theatre.’ News18, May 22, 2012. Accessed August 8, 2018. https://www.news18.com/blogs/india/h-s-shivaprakash/the-evolution-of-modern-indian-theatre-14277-746839.html.

Swamy, G Kumara. ‘Actor Training: Contexts, Methods and Practices in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka.’ In Theatre teaching and training in South India with a special focus on actor training contexts, 154–230. PhD thesis, Department of Theatre Arts, University of Hyderabad, 2011.

Star of Mysore. ‘Rangayana To Stage ‘The House of Bernarda Alba’ From July 21.’ SoM, Mysore, 20 Jul 2019.

Tendulkar, Vijay. ‘The Genius of Karnath.’ The Hindu, Magazine, New Delhi, September 15, 2002. Accessed August 8, 2018. https://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-features/tp-sundaymagazine/the-genius-of-karanth/article28517885.ece

The Hindu. ‘Kannada’s Only Kailasam.’ The Hindu, Bangalore, July 29, 2005.

The Hindu. ‘Weekend theatre will be one-day affair.’ The Hindu, Bangalore, May 13, 2006.

The Hindu. ‘Kuvempu’s ‘Ramayana Darshanam’ is now a play.’ The Hindu, Bangalore, Nov 19, 2018.