The ‘novel’ is usually regarded as a Western genre of literature that found its way into South Asian literary culture during the nineteenth century as a by-product of colonialism. However, it can be argued that it was assimilated into modern Indian languages not in its original name of ‘novel’ but in native nomenclatures, such as kadambari in Marathi and Kannada, upanyas in Bangla and Hindi, and naval katha in Gujarati, which connotes the process of indigenisation that the genre of novel underwent in Indian languages. In its early days, literary criticism in modern Indian languages evaluated these new narratives in prose ‘in terms of their closeness to the Western models.’[1] This resulted in realism and mimesis becoming the touchstone in literary evaluation of the novel in modern Indian literatures, a practice that reflects in the subsequent processes of canonisation where the ‘real’ is always preferred over the ‘fabulous’ and the ‘marvellous’. Nonetheless, the realistic novel did not immediately take hold of the South Asian consciousness. The ‘fabulous’ and the ‘marvellous’ modes in the pre-print manuscripts and oral traditions also coexisted within the emerging network of print and exerted their own ‘volatile influence and claims upon the consumers of the print.’[2]

The Mechanics of Magic: The World of Chandrakanta

After a sketchy beginning, the novel in Hindi really took off in the 1890s with the runaway success of Devkinandan Khatri’s (1861–1913) Chandrakanta (1888). Khatri did not replicate ‘the realism of British Victorian fiction’ that had emerged as a ‘universal paradigm of writing novel’[3] in colonial India. On the contrary, he remodelled the ‘ruzm, buzm, husn, and aiyaari’[4] of the Persian dastan[5] world and naturalised it in a visibly Hindu milieu, whereby it celebrated the Hindu martial and moral values. Set in an abstract Indian past, the narrative of Chandrakanta traverses narrow, contorted and rugged terrains, and takes the reader through mysterious forts and magical forests, full of miraculous illusions and memorable incidents. The novel, in the author’s own confession, is about the aiyaars who served in the courts of kings as spies and resolved conflicts between warring kingdoms with their slyness without shedding a single drop of blood. As masters of disguise, the aiyaar literally carried a bag of tricks to outsmart their enemies and, in the process, displayed admirable ethical values as well as outstanding courage and impeccable intelligence.

Khatri not only gave a visibly Hindu outlook to the Persian dastan, but also transformed the tilism of dastan in the spirit of modernity. He gave it an ‘imprint of the new mechanical age’,[6] whereby he sought to provide scientific explanations for the magical marvels of his stories. The story is told mimetically as it begins with two characters conversing, instead of the narrator providing an exposition to either the characters or the story. It is from this conversation that the context of the story is revealed to the readers. The reader must pay attention to these dialogues, which are abundant throughout the novel, to understand the story. Diegesis is used most notably to resolve any confusion accruing in the narrative. This mimetic element is crucial, for it establishes a mystery that binds the reader’s interest in the narrative. Previous works in Hindi that fashioned themselves as upanyas (novel) also valued the dramatic representation of events or mimesis over straightforward recounting of the story or diegesis, which is a dominant characteristic of the pre-print tradition. However, Khatri’s genius lay not just in using a consistent mix of mimetic and diegetic representation but also in the ingenuity of this usage.

Khatri’s fictions provided wholesome entertainment through marvellous adventures full of unforeseen twists and turns. Intricately entwined around a cogent conflict, the narrative progresses swiftly by weaving situations hinged upon surprise and suspense that entertain the readers with their ensuing enigma. Although the narrator illuminates this enigma in the following chapters, he does so only for constructing another enigmatic episode. The simple syntax and colloquial vocabulary ensured easy accessibility for the neo-literate readership of the turn-of-the-century Hindi literary system, which combined with the novel’s unique narration of a familiar story in a sensational structure to make it the earliest commercial success in Hindi.

Written in four parts, Chandrakanta’s instant success prompted Khatri to take up novel-writing as a full-time career, which he did by writing Chandrakanta Santati in 24 parts, apart from Bhootnath, which his son, Durga Prasad, finished after Khatri’s untimely death in 1913. Noted Hindi critic Rajendra Yadav calls these three books different parts of a single novel, the Chandrakanta phenomena that gripped generations of Hindi readers.[7] Khatri brought out the Upanyas Lahiri periodical in 1894 for serialising his subsequent novels before publishing them in book form. He did so under the imprint of Lahiri Press, which he founded in 1898 in Banaras, although he often printed his novels at other presses.[8] In doing so, he became what Jennifer Dubrow has called a ‘print entrepreneur’[9] in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Hindi literary system.

Narrating History: The Origin of a Genre

Hindi literary critic Gopal Rai has noted the 29 years between 1890 and 1919 as the time when novels flooded the literary market.[10] In this period, several writers tried their hand at novel writing, and a few went on to establish subgenres of the novel in Hindi. Among these, the historical and the detective varieties gained significant popularity. While Khatri’s objective behind writing novels was merely wholesome entertainment, the writers who took up novel-writing as a full-time career, following Khatri’s resounding success, were also conscious of the secondary status of Hindi compared to Urdu in colonial North India.[11] For this, these writers envisioned a new variety of the novel that could be edifyingly entertaining for the readers. Writing novels for these Hindi-hitaishis[12] was as much a way to make money as to serve the cause of popularising Hindi as a language of national significance. Kishorilal Goswami (1864–1932) was one such influential actor who used the genre of novel to mediate history, and after his example in the 1890s, several writers like Ganga Prasad Gupt and Jairamdas Gupt followed suit in the 1900s. In this sense, the genre of historical novel or aitihasik upanyas[13], as these writers called it, was a 'genre introduced' in Hindi, a typological category used by literary scholar Francesca Orsini to classify the early publishing activities in Hindi.[14]

Since a genre ‘does not exist independently but arises to compete or to contrast’[15] with existing genres, the introduction of historical novel must be seen in terms of two interrelated characteristics of the turn-of-century Hindi literary system. Firstly, during the 1880s, the enthusiasm of Hindi writers for writing the Hindu past prompted them to seek inspiration from comparatively developed literary systems, for which Bengal, where the genre of historical novel was already established, captivated their imagination.[16] Secondly, the Hindi socio-semiotic entrepreneurs[17] in the 1890s and 1900s were coming to terms with the fact that Hindi needed a comprehensive body of literature in several subjects for becoming a language of national significance.[18] History was of special importance among these subjects.[19] These actors were also critical of the abundance of low-quality novels in Hindi that they thought had adverse moral effects on the reading public.[20] It is this opportunity that the actors who were active in the commercial publishing industry seized. They solved both these problems at once by envisioning the aitihasik upanyas as a means of providing ‘edifying entertainment’ to the reading public in the commercial publishing industry of turn-of-the-twentieth-century Hindi literary system, which Orsini has otherwise explained as the ‘field of action’ where books were produced both to entertain and instruct.[21]

The Architect of a Genre

Kishorilal Goswami was the grandson of Goswami Kedarnath, the chief priest of Vrindavan’s Atalbihari Ji Temple. He was proficient in Sanskrit and knew Persian, Bangla and Urdu as well. His maternal grandfather, Goswami Krishna Chaitanya Dev, was the literary mentor of Bhartendu Harishchandra (1850–1885), whose literary gatherings Goswami frequented as a child. Goswami started writing at a time when Hindi literature was in its formative phase, after a few luminaries under the tutelage of Harishchandra had lent considerable impetus to the formation of modern literature in Hindi. The novel had hardly shown signs of novelty, other than few stray examples including Khatri’s Chandrakanta, while play and poetry mostly comprised of derivative works from Bangla or Marathi. Both Khatri and Goswami played an important role in the Hindi literary system towards the development of the novel. Apart from 65 novels and novelettes, of which around 11 were historical, Goswami also published[22] original works of poetry, alongside what has been recognised as the first short story in Hindi, ‘Indumati’.[23]

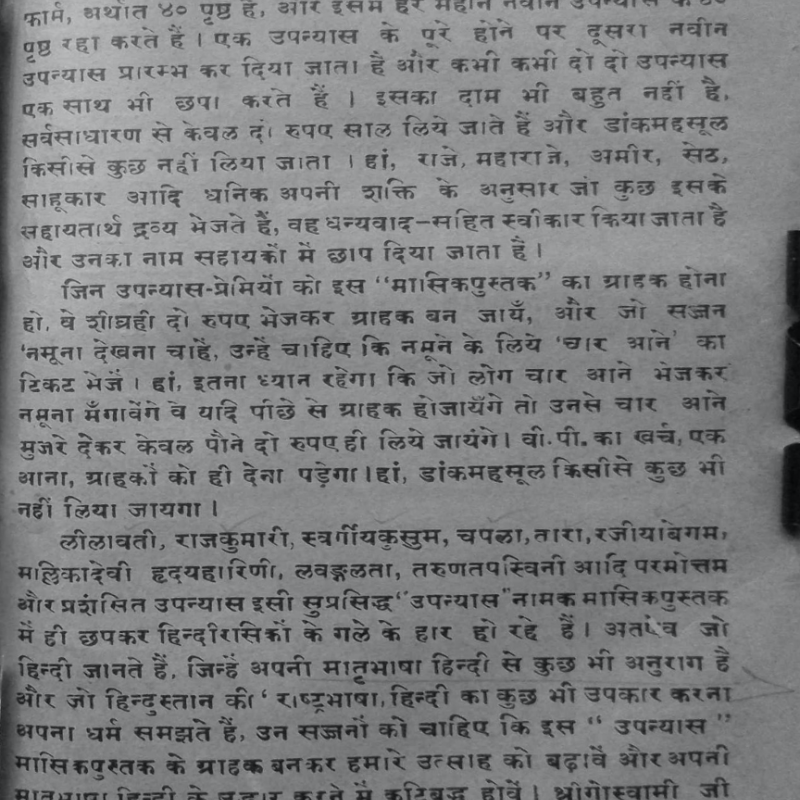

In the 1890s, Goswami left Vrindavan and made Banaras (now Varanasi) his home, where he published his first novel Pranayini Parinay in 1890 from the Bharat Jivan Press, although it was written three years ago in 1887. In 1890, Goswami also serialised his first historical novel Hridayiharini wah Adarsh Ramini in the Hindi daily Hindustan under the editorship of his friend Pratapnarayan Mishra (1856–1894). After working in centres of erstwhile Hindi literary systems, he returned to Vrindavan to partake in the emerging commercial publishing industry. It was to this end that he set up a 40-page monthly periodical called Upanyas in 1898, which he not only published from his Sudarshan Press in Vrindavan but also distributed himself, making him a print entrepreneur in colonial North India.

The monthly issue of Upanyas, where most of his novels were first serialised, often carried its own advertisements, which testify the kind of fiction that appeared in its pages:

रंगीले, सजीले, भड़कीले, चटकीले, अनूठे, अनोखे, जानदार और शानदार बेजोड़ उपन्यासों की यह बहुत पुरानी और बढ़िया मासिक पुस्तक है जो लगभग पिछले सोलह बरसों से निकल रही है। इस मासिक पुस्तक में हर महीने चुहचुहाते और फड़कते हुए चित्र-विचित्र घटनाओं से भरे हुए नए-नए उपन्यास छपा करते है जिनका हर पेज दिलचिस्प, तर्बियतदारी, रोचकता और मनोहरता से लबालब भरा रहता है।[24]

(This is an old and outstanding monthly book of colourful, ornate, rousing, enticing, uncommon, unconventional, lively and splendidly unmatched novels that have been coming out for the last sixteen years. Every month, new novels full of sensational, zestful, and outlandish events, are published in this monthly whose every page is enthralling, edifying, exhilarating, and exciting.)

Indeed, entertainment is the most important function of these novels, which Goswami achieves by building on Khatri’s example. He, however, was not blind to contemporary social issues and incorporated them into the narrative to serve as a commentary on the ideal moral conduct in society. Goswami’s historical novels are essentially romances that take for their plot the resolution of a conflict, usually arising from the antagonist’s sexual aggression on the protagonist or his kin. This aggression also has political dimensions, for it threatens the protagonist’s political sovereignty, who, in most cases, governs a kingdom peripheral to the antagonist’s area of rule. As the narrative progresses towards the resolution of this conflict, the protagonist displays exemplary signs of courage, intellect, moral conduct and resistance whereas the antagonist reveals his immoral, cowardly tactics. The author exemplifies the ideal moral conduct for his readers by contrasting the behaviour of the protagonist with that of the antagonist, through the rhetorical device of juxtaposition, a recurring feature of these novels. In doing so, Goswami not only historicises these values as intrinsic to Indian civilisation but also presents them as exemplary qualities worthy of emulation in the colonial present.

Suspense and Surprise: The Building Blocks of the Story

Suspense is a major ingredient of the early novel in Hindi, and Goswami’s historical novels are no different. The dependence on suspense and mystery, alongside erotic titillation in the form of romance, fulfils early Hindi novels’ objective of providing wholesome entertainment. This serves the interest of the neo-literate readership of the erstwhile Hindi region, a characteristic that Orsini has explained in terms of cultural critic Ermanno Detti’s thesis of ‘sensuous reading’,[25] where a strong emphasis on pleasure is necessary to build a taste for reading. The reliance of the early Hindi novels on suspense could also be attributed to the fact that these novels were serialised in periodicals before their publication in book form, because of which they had to keep the readers at tenterhooks so that they eagerly await the publication of the next issue.

Goswami builds suspense using a variety of techniques, among which partial viewpoint and the controlled release of information are the most common, the widespread use of which has been noted by Orsini in the early detective novels of Hindi.[26] The plot progresses as a mystery that must be slowly revealed to the reader in order to sustain the thrill of reading until the very last page. Twists and turns constantly betide the story and the plot comprises of several connecting stories, all of which converge towards a fulfilling end.

Disguise, mostly in the form of cross-dressing, is another recurring motif that these novels borrow from previous works like Chandrakanta, and here too it serves to build intrigue and mystery. While in Chandrakanta, it is the aiyaar who specialises in disguise, Goswami’s historical novels completely remove this deceptive spy-like figure, albeit retaining its characteristics such as intelligence, agility and courage for the hero or the heroine. Like Jit Singh in Chandrakanta, Goswami’s historical novels introduce a character early on in the narrative who aids the protagonist countless times in his/her quest. The readers are left guessing the true identity and motivations of this mysterious character, which the author reveals only towards the end in a manner reminiscent of Chandrakanta. This intensifies the suspense and surprises the readers when the secret is finally given away.

The mysterious tunnels, secret passageways, and enigmatic prisons of Chandrakanta are not entirely missing from Goswami’s historical novels, even though they are not as commonplace. However, in putting these within the walls of historical forts, the novelist not only uses these motifs for surprising the reader, but also suggests the past glory of the rulers, mostly Hindus, who built them. Tilism is not as extensive in these novels as it is in Chandrakanta for such descriptions runs the risk of giving away the veracity of the narrative, even though it remains latent enough to keep the readers engaged.

Fashioning Hindi: Language in Goswami’s Historical Novels

Goswami started his literary journey at a time when the Hindi-Urdu language debate in colonial North India was brewing intensely. While several Hindi literary actors favoured a Sanskritised Hindi, markedly distinct from Urdu, such an artificial diction hardly had any takers among the neo-literate consumers of print, who otherwise used entirely different linguistic registers in their everyday life. Chandrakanta’s success owed as much to its use of everyday vocabulary, drawing unhesitatingly from Urdu and other speech varieties prevalent in North India, as to its simple syntax that complements its swift narrative speed. Goswami, who was more sympathetic to the cause of the Hindi movement than Khatri, resolved this issue by choosing the middle path. He fashioned a Hindi in his novels that was as easy to understand for a diverse readership as it was agreeable to the ongoing struggle of the formation of Hindi language.

Goswami’s literary language varies from situation to situation as he meanders between Sanskritised Hindi and Perso-Arabic Hindustani, according to the context of his characters. This is not unlike the rules of appropriate speech in Sanskrit poetics. While his Muslim characters use Perso-Arabic vocabulary and draw from the poetic tradition of Persian, his Hindu characters use ornate speech in Sanskritised Hindi, revealing a Sanskrit heritage. Although this should be read alongside the debate around ‘identity and language’ in the erstwhile Hindi public sphere, literary historian Ramchandra Shukla, who favours a sharper distinction between Urdu and Hindi, has taken Goswami to task for his use of ‘Urdu-e-Mualla’ by asserting that this use of a mixed language has diminished the ‘literariness’ of Goswami’s novels.[27] On the contrary, Rai has lamented the use of context-specific language in Goswami’s prose as a characteristic that betrays realism.[28] He does so while pointing out a transition in the use of language in Goswami’s novels where his later work shows a more democratic diction in comparison of his earlier novels, which employ a more Sanskritised vocabulary.[29]

Historical Memory: Inventing a Tradition of Antagonism

Goswami’s historical novels can be seen as part of the larger tradition of early historical novels in Indian languages that derive their material from colonial historiography and indulge in Muslim bashing by portraying the Muslim rule in India in negative light. In contrast to this portrayal of Muslims, these novels exemplify the moral conduct of Hindus in the past for negating the colonial difference, which could be defined as a web of power relations that helped the British colonisers maintain their control over the colonised population.[30] Muslim characters in Goswami’s novels appear as lascivious, cruel, and power-hungry caricatures who indulge in all sorts of debaucheries and oppress their subjects for fun. Their rule is cruel and oppressive for the Hindus, which the author explains, in line with most contemporary Hindi literary actor, as the genesis of every problem faced by the Hindus in the present. However, not all Muslim characters are bad in Goswami’s fictional world, and there are shades of good Muslims who are depicted as righteous, composed, learned and skilled.

The point to note about Goswami’s historical novels is the theme of resistance against foreign rule. These foreigners are not British but Muslims who have come to rule India from outside and must be thrown out. The Hindus, as in the figure of Swami Brahmanand in Sultana Razia Begum (1904), dream of establishing Hindu rule one day by ending the tyranny of the Muslim rulers. This oppression under foreign rule parallels the contemporary realities of the British rule, but the author chooses not to explicitly show the British in bad light. Along with the historical memory of oppression under the Muslim rule, it is the memory of a utopian Hindu rule that these novels manufacture for the contemporary readership. In reminding their readers the ‘real glory of Aryans’[31] in the past, where they valiantly resisted foreign oppression, these novels suggest the need for a similar resistance in the present.

By emblematising the actions of real and fictional characters as either moral or immoral, Goswami’s historical novels use the past to delimitate a moral universe for the Hindu community that could contribute towards the making of the nation in the present. In historicising these values, they not only displace the colonial charge against the Indian civilisation of lacking moral and heroic values,[32] but also invent a tradition for the present. The past in these novels thereby becomes a site of exemplarity—Hindu exemplarity—with which the readers in the present are persuaded to associate. However, this is established at the cost of stereotyping the Muslim, the consequences of which continue to reverberate in North Indian cultural politics.

Fabricated Facts: The Question of Historical Authenticity

Goswami’s historical novels use history only as a backdrop and do not care much about the historicity of the events they recount. While there is a conscious attempt to make the characterisation of the past believable, historical authenticity is compromised to serve the primary goal of the narrative: extolling Hindu exemplarity. Historical truth and facticity are secondary in these novels, and there is widespread use of creative license, to an extent where the stories become anachronistic and historically inauthentic. Goswami had been reprimanded for the historical flaw of his novels even by his contemporaries. However, the historical inauthenticity of these novels hardly diminished their popularity and they continued to command a considerable readership during his lifetime. This supports the claim that historical authenticity, just as it is for other early writers of historical novels in India,[33] is not important for Goswami. It is for the wider goal of exemplifying a certain conduct in contemporary society that he explores the past, which albeit concocted, constantly legitimises itself as valid and authentic through a series of narratological moves.

The Function of the Genre

Goswami and other writers of the historical novel were indeed Hindu chauvinists concerned with upholding the ‘superior moral values of the Hindus.’[34] However, this only bids a deeper engagement with these novels, because they are implicated in shaping the emerging Hindi public sphere debates on the formation of the community around the markers of religion, language, and nation. In uttering ‘history’s hidden discourse’ where an ‘imaginary subject’ takes upon ‘real predicates’, these fictions pursue the ‘counterfactuals’ to recorded history, whereby they seek to ‘shift and displace’ the historical record.[35] Moreover, they also contrive a historical memory for a society desperate for a sense of collective identity, stripped of all signs of excess, inferiority, and humiliation, upon which the ideals of nation would be erected. If on one hand, these past-based novels exhibit different facets of individual improvement in the turn-of-the-century Hindi public sphere, they also reveal the Other against whom the Hindi literary actors shaped the identity of their Self. More than that, the aitihasik upanyas offers an alternative genealogy of the Hindi novel that moves beyond hierarchising realism as the central characteristic of the novel. Within the structural complexities of these novels lie the efforts of a generation in shaping the literary tastes of another.

Notes

[1] Mukherjee, ‘Epic and Novel,’ 596–631.

[2] Joshi, In Another Country: Colonialism, Culture, and the English Novel in India, 39.

[3] Mukherjee, Introduction to Early Novels in India, vii.

[4] Orsini, Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaining Fictions in Colonial North India, 206.

[5] The Hindi renditions of Urdu dastans were extremely popular during the 1860 and 70s. Among these Rajab Ali Beg Saroor’s Fasana-e-Ajaayab (1832–42) is notable. A monumental prose work running into seven volumes and 7,500 pages, Tilism-e-Hoshruba, which was a part of Dastan-e-Aamir Hamza also gained popularity among the readers during this period. See Gopal Rai. Hindi Upanyas ka Itihas, 71–72.

[6] Rai, Hindi Upanyas, 72–73, quoted in Orsini, Print and Pleasure, 210.

[7] Rajendra Yadav, ‘Dayaniye Mahanta ki Dilchasp Dastan’ in Devkinandan Khatri’s Chandrakanta. (New Delhi: Radhakrishna Paperbacks, 2012), p. iii.

[8] Orsini, Print and Pleasure, 201.

[9] Dubrow, Cosmopolitan Dreams: The Making of Modern Urdu Literary Culture in Colonial South Asia, 15–22.

[10] Rai, Upanyas Kosh, Vol. 1, 43.

[11] The Hindi-Nagari movement defined much of the late-nineteenth-century- and early-twentieth-century Hindi literary system in colonial North India. For an overview see Rai, Hindi Nationalism. Also see Dalmia, The Nationalization of Hindu Traditions, 146–221; King, One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. Read here: courtesy of Columbia University through the generous permission of the author.

[12] The Hindi literary actors used this term for ‘self-fashioning’, often on the title page of their books. Hitaishi refers to the semantic field associated with words like sympathizer or well-wisher, but the term in turn of the twentieth century Hindi literary system denotes a person who serves the cause of Hindi.

[13] These writers categorised their narrative as aitihasik upanyas on the title page, although it is pertinent to point out that they also referred to their narrative with several traditional appellations like akhyayika or akhayaan, katha, and qissah within the body of the text.

[14] Orsini, Print and Pleasure, 226.

[15] Cohen, ‘History and Genre,’ 206.

[16] Durgeshnandini was translated between 1882–1884 by Gadadhar Sinha and in 1894 by Radhakrishna Das. Harishchandra and Pratapnarayan Mishra brought out separate translations of Rajsingh in 1894, the former posthumously. Romesh Chandra Dutt was translated first in 1889. See Rai, Hindi Upanyas Kosh, Vol I. Also see Bhattacharya, ‘Bankimchandra’s Influence on Indian Literature’, 359–381.

[17] Itamar Even-Zohar uses socio-semiotic entrepreneurs for a group of people like poets, writers, critics, philosophers among others who compose a vast corpus of texts in order to “justify, sanction, and substantiate the existence, or the desirability and pertinence” of nations. See Itamar Even-Zohar, ‘The Role of Literature in the Making of the Nations of Europe’ in Papers in Culture Research, ed. Itamar Even-Zohar, 107–128.

[18] While Sujata Mody has shown such concerns in a 1911 essay by Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, such issues appear in the Hindi public sphere much earlier, most notably in a 1902 essay by Sakal Narayan Pandey. See Pandey, ‘Hindi Sahitya ki Vartaman Dasha.’ For Mody’s reading of Dwivedi’s essay, see Mody, The Making of Modern Hindi: Literary Authority in Colonial North India, 108–117.

[19] Radhakrishna Das in an essay entitled ‘Puratatva’ (1897) speaks of the lack of history in Hindi and encourages Hindi writers to take up history writing before supplying a brief module on the methods of history writing. See Das, ‘Puratatva’ in Radhakrishan Granthavali, 143–153.

[20] Mody’s assessment of the ‘Sahitya Samachar’ series cartoons by Dwivedi right after taking over the editorship of Saraswati points out such attitude towards the contemporary novel. See Modi, The Making of Modern Hindi, 54–55.

[21] Orsini, Print and Pleasure, 226.

[22] For a broader overview of Goswami’s publishing activities, an historical account of which is still wanting, see Srivastava, Kishorilal Goswami: Bhartiya Sahitya ke Nirmata.

[23] For a brief overview of the story, see Schokker, ‘Kishorilal Goswami’s Indumati.’

[24] Srivastava, Kishorilal Goswami: Bhartiya Sahitya ke Nirmata, 38. All Hindi translations are by the author of this essay.

[25] Orsini, Print and Pleasure, 22 and 182.

[26] Orsini, Print and Pleasure, 42.

[27] Shukla, Hindi Sahitya ka Itihas, 402.

[28] Rai, Upanyas ki Sanranchna, 60.

[29] Rai, Hindi Upanyas, 91–92.

[30] See Guha, Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India; Chatterjee, The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial History in Partha Chatterjee Omnibus.

[31] Chug, Aitihasik Upanyas, 53.

[32] See Guha, Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India.

[33] For a similar exposition in Marathi, see Deshpande, Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700–1960, 154–157.

[34] Mukherjee, Realism and Reality: The Novel and Society in India, 61.

[35] Kaviraj, The Unhappy Consciousness: Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay and the Making of the Nationalist Discourse in India, 112–134.

Bibliography

Bhattacharya, Vishnupada. ‘Bankimchandra’s Influence on Indian Literature.’ In Bankim Chandra: Essays in Perspective, edited by Bhabatosh Chatterjee, 359–381. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1994.

Chatterjee, Partha. The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial History in the Partha Chatterjee Omnibus. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Chug, Satyapal. Aitihasik Upanyas. New Delhi: Rajkamal Press, 1974.

Cohen, Ralph. ‘History and Genre.’ New Literary History 17, no. 2 (Winter: 1986): 203–18. Accessed January 20, 2019. doi:10.2307/468885.

Dalmia, Vasudha. The Nationalization of Hindu Traditions. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Das, Radhakrishan. ‘Puratatva.’ In Radhakrishan Granthavali, edited by Babu Shayamsundar Das, 143–153. Allahabad: Indian Press, 1930.

Deshpande, Prachi. Creative Pasts: Historical Memory and Identity in Western India, 1700–1960. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2013.

Dubrow, Jennifer. Cosmopolitan Dreams: The Making of Modern Urdu Literary Culture in Colonial South Asia. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2018.

Even-Zohar, Itamar. ‘The Role of Literature in the Making of the Nations of Europe.’ In Papers in Culture Research, edited by Itamar Even-Zohar, 107–128. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University, 2010.

Guha, Ranjit. Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Joshi, Priya. In Another Country: Colonialism, Culture, and the English Novel in India. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Kaviraj, Sudipta. The Unhappy Consciousness: Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay and the Making of the Nationalist Discourse in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995.

King, Christopher. One Language, Two Scripts: The Hindi Movement in Nineteenth Century North India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Mody, Sujata. The Making of Modern Hindi: Literary Authority in Colonial North India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Mukherjee, Meenakshi. ‘Epic and Novel.’ In The Novel: History, Geography, and Culture - Volume 1, edited by Franco Moretti, 596-631. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

———. Introduction to Early Novels in India, by Meenakshi Mukherjee, vii-xix. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2002.

————. Realism and Reality: The Novel and Society in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Orsini, Francesca. Print and Pleasure: Popular Literature and Entertaining Fictions in Colonial North India. New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2009.

Pandey, Sakal Narayan. ‘Hindi Sahitya ki Vartaman Dasha,’ Samalochak 1, no.2 (1902): 3-18.

Rai, Gopal. Hindi Upanyas ka Itihas. New Delhi: Rajkamal Prakashan, 2005.

———. Upanyas Kosh – Vol 1. Patna: Grantha Publication, 1968.

———. Upanyas ki Sanranchna. New Delhi: Rajkamal Prakashan, 2006.

Schokker, G.H. ‘Kishorilal Goswami’s Indumati.’ In Imagining Indianness: Cultural Identity and Literature, edited by Diana Dimitrova and Thomas de Bruijn, 111-130. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Srivastava, Garima. Kishorilal Goswami: Bhartiya Sahitya ke Nirmata. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. 2017.

Shukla, Ramchandra. Hindi Sahitya ka Itihas. New Delhi: Vani Prakashan, 2018.

Yadav, Rajendra. ‘Dayaniye Mahanta ki Dilchasp Dastan.’ In Devkinandan Khatri’s Chandrakanta. i-xxxix. New Delhi: Radhakrishna Paperbacks, 2012.