Once the novel arrived on the Hindi literary scene in the late nineteenth century, several eminent Hindi hitaishis[1] (benefactors) realised its scope for familiarising the emerging readership with the Indian past, which usually meant an exaggerated Hindu past resisting the cruelty of the Muslim rule. Most reviewers regarded the historical novel as a socially useful form of literature, hence more respectful, primarily because of its pedagogical value. This not only added to its popularity but also prompted almost every prominent person of letters who fancied himself as a novelist to try their hands at the historical novel. Here, we look at some of the main Hindi historical novelists from the first two decades of the twentieth century.

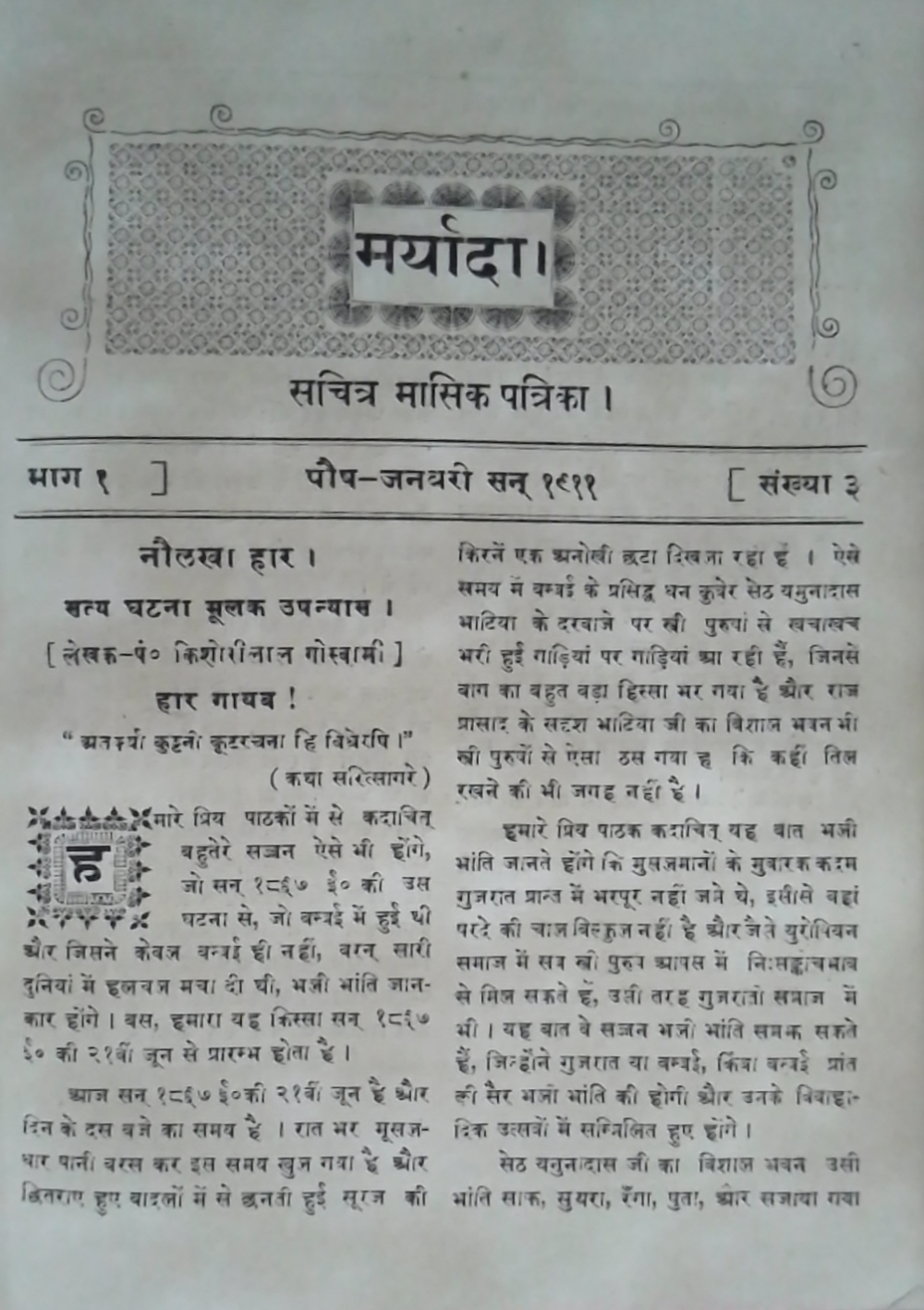

Kishorilal Goswami

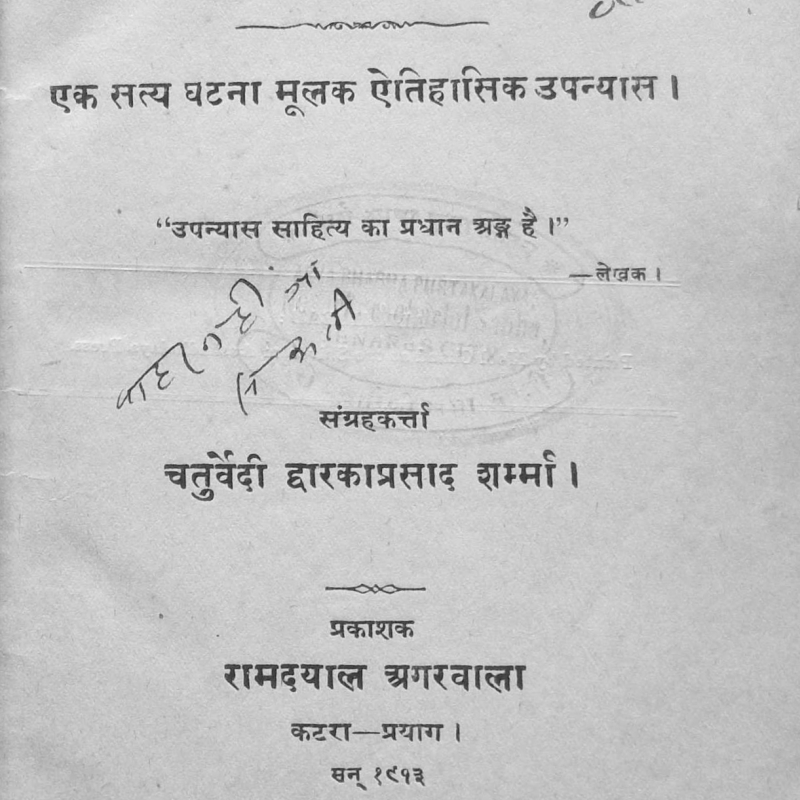

Born in a family of Vaishnava priests from Vrindavan, Kishorilal Goswami (1865–1932) was a scholar of Sanskrit and knew Persian, Bangla and Urdu well. As a child, he frequented the literary gatherings of the famous Hindi writer Bhartendu Harishchandra (1850–1885), where he might have found the inspiration to take up novel writing in Hindi. Goswami is mostly known today as the writer of the first ever short story in Hindi, titled ‘Indumati’. Originally published in 1902, ‘Indumati’ localises Shakespeare’s The Tempest in the Vindhya hills to tell the tale of a Hindu king usurped by Ibrahim Lodhi in the sixteenth century.

Goswami played an important role alongside Devaki Nandan Khatri (1861–1913) towards the development of the Hindi novel in the last decade of the nineteenth and first two decades of the twentieth century. He wrote around 65 novels, few among which were also adaptations from Bangla. (Fig. 1)

After working in erstwhile centres of the Hindi publishing industry, primarily Varanasi, Goswami returned to Vrindavan to partake in the emerging commercial fiction publishing industry. For this, he established a 40-page monthly periodical, Upanyas Masik Pustak, in 1898, which he published intermittently for the next several years from various presses before establishing his own publishing house, Sri Sudarshan Press, in 1913 in Vrindavan. Most of Goswami’s works appeared in the pages of Upanyas Masik Pustak which reached a circulation of about 500.

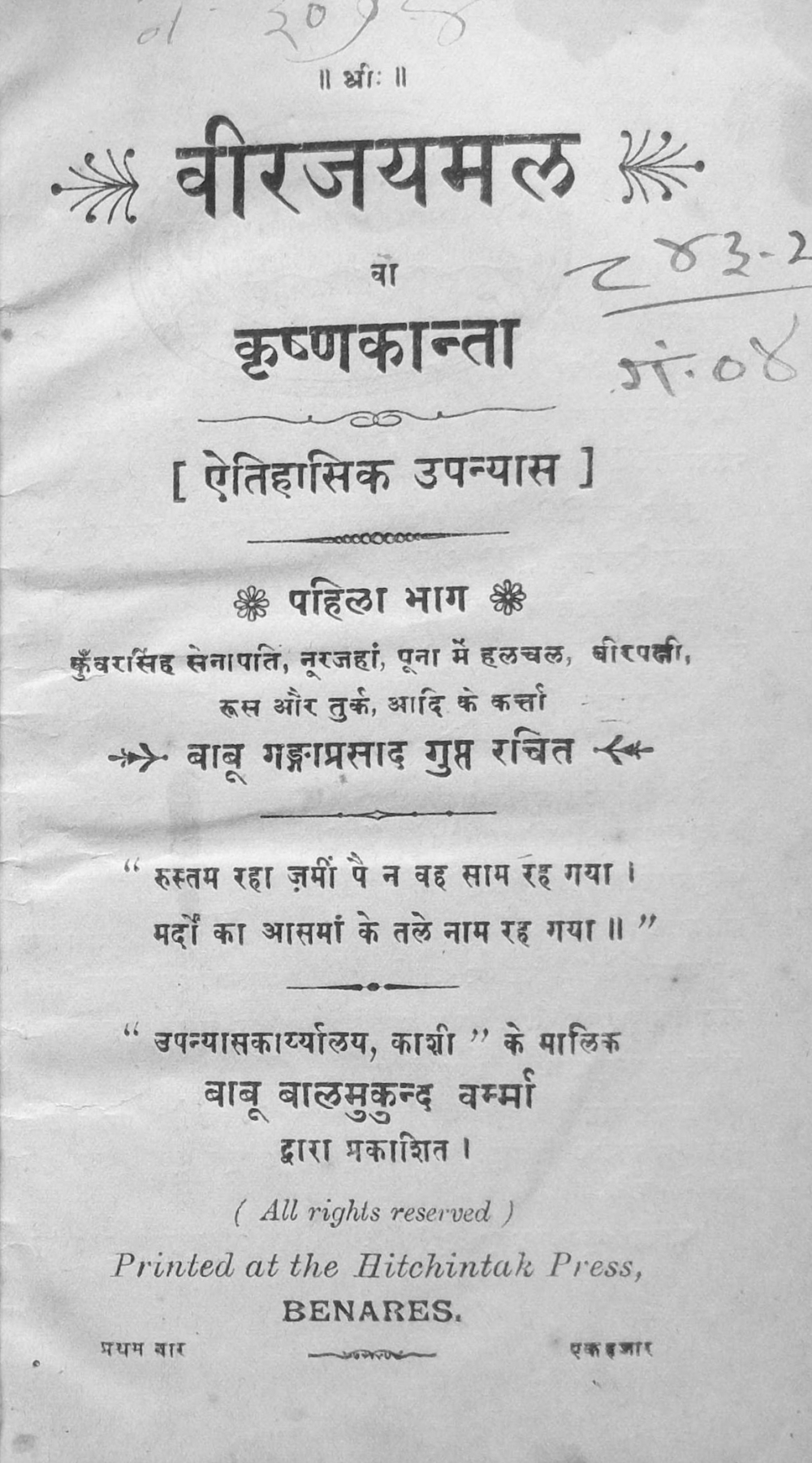

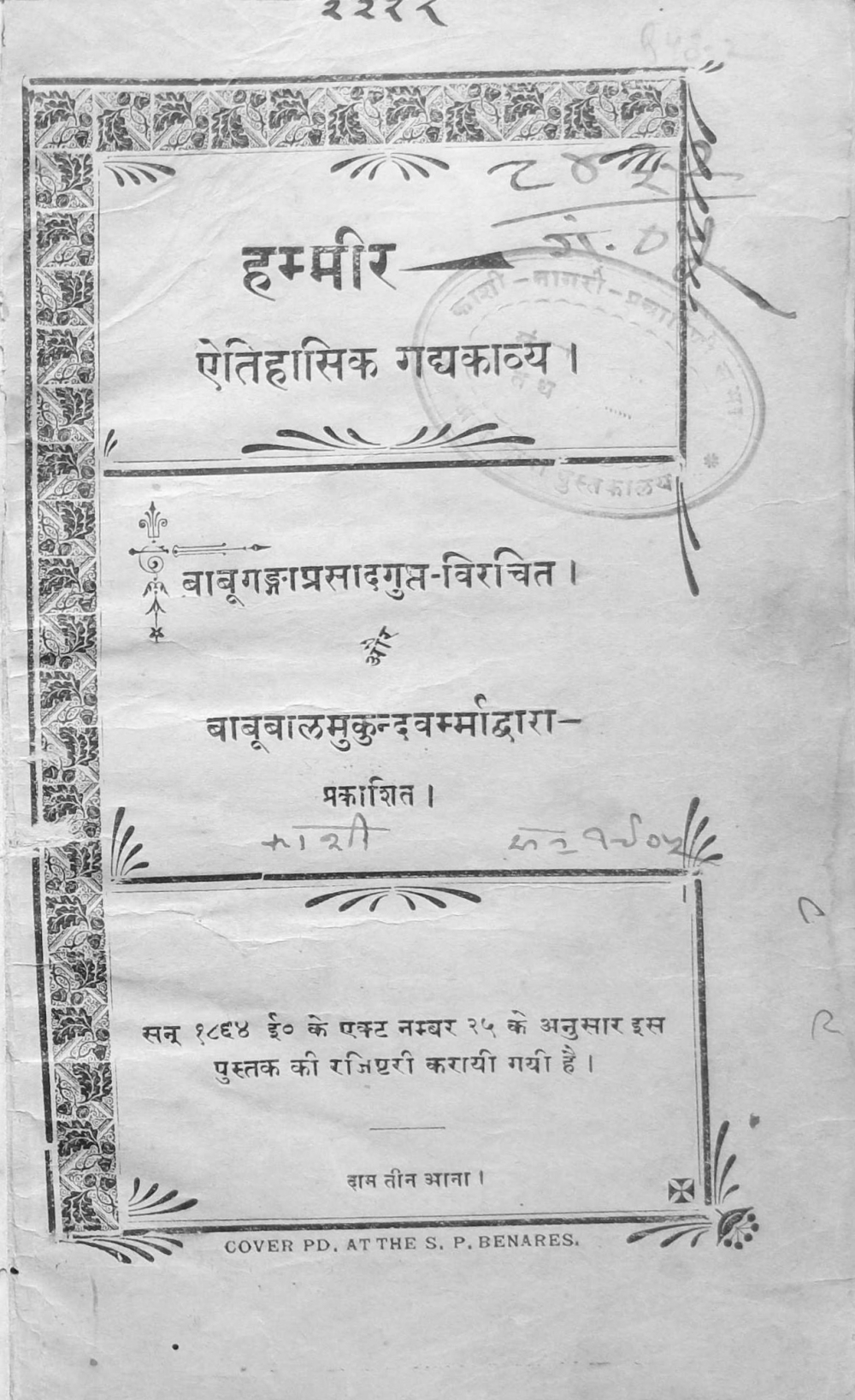

Ganga Prasad Gupt

Ganga Prasad Gupt (1885–?) is another major writer of historical novels from this period. Almost all his novels were originally published by the Bharatjeevan Press, Varanasi, from where he also edited the weekly Bharatjeevan. In a review from the Pustak-Pariksha series in the monthly Saraswati, January 1905, writer and editor Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi hails Ganga Prasad as a prolific writer with an unmatched knack for turning out one book after another.[2] He also translated profusely into Hindi from English and Bengali. Among his historical novels, Veer Jaimal (1903) and Hammir (1905) are noteworthy.

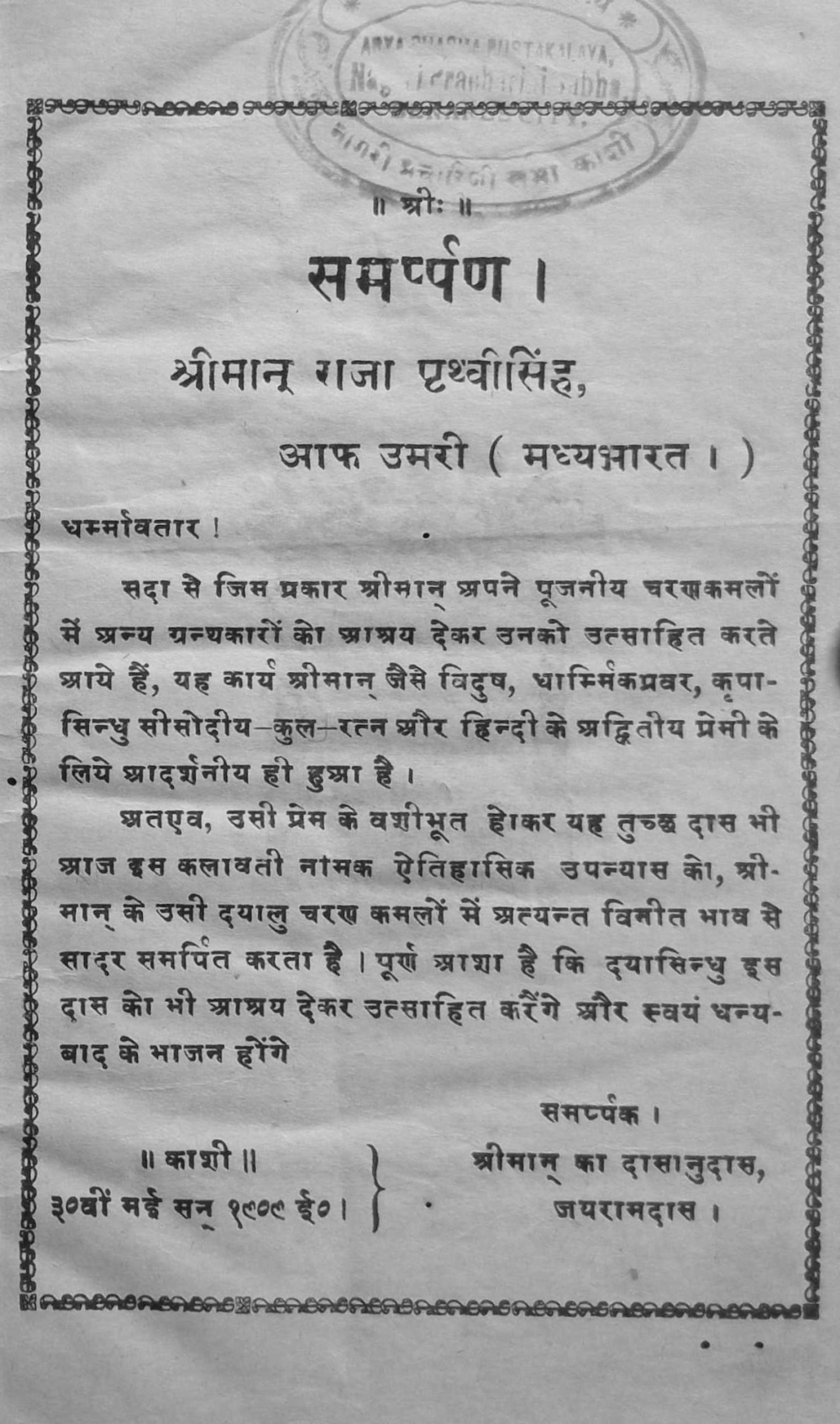

Jairam Das Gupt

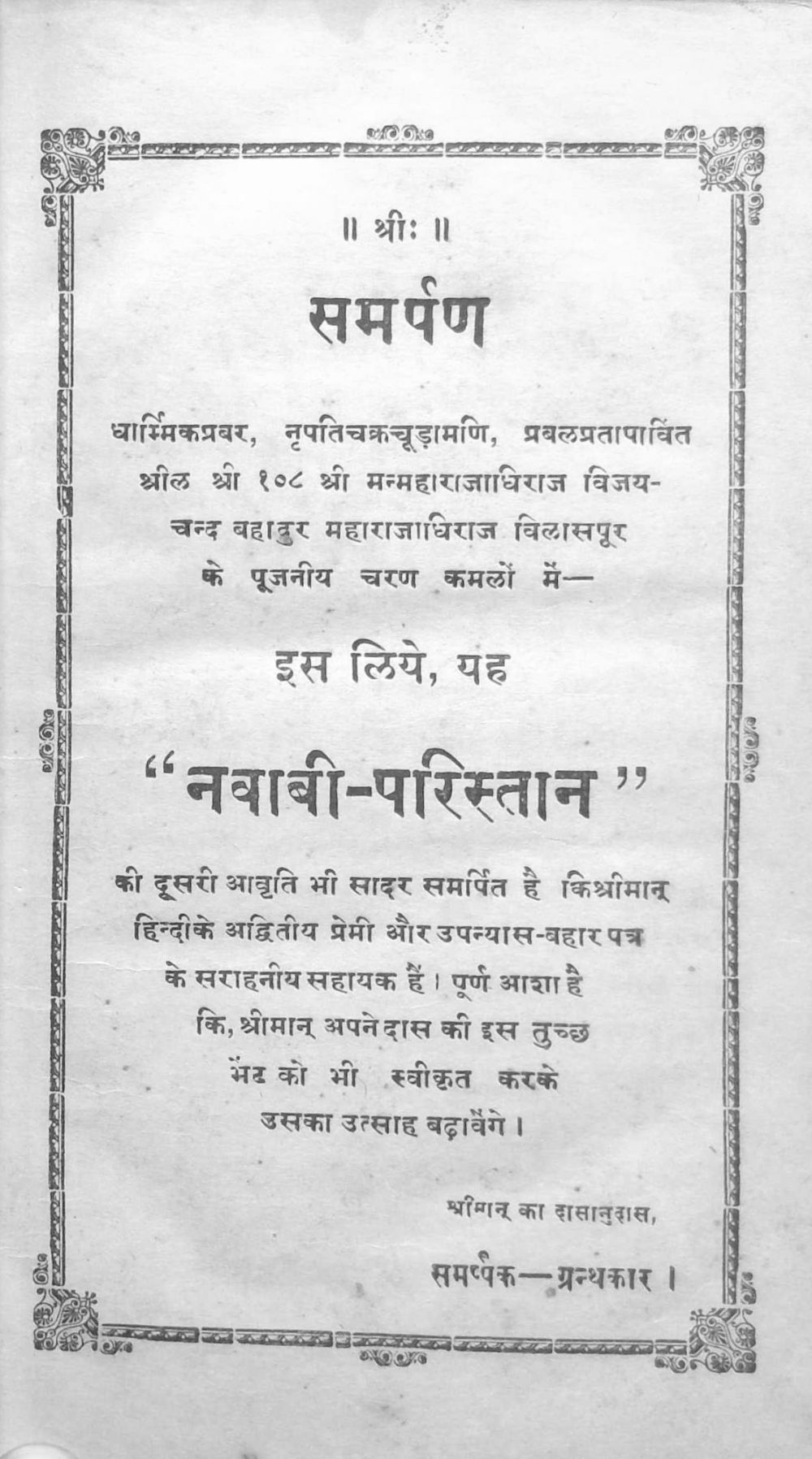

Jairam Das Gupt is another prominent historical novelist from this period who ran the Upanyas Bahar Office, a major publishing house in Varanasi. He wrote at least 11 historical novels, among which Kashmir Patan (1907) and Nawabi Paristan (1908) are the most notable. Like his contemporaries, he also translated works from other languages into Hindi, and in this regard his translation of Philip Meadows Taylor’s A Noble Queen as Chandbibi wah Veer Mani (1909) is significant.

Lajjaram Mehta:

As the editor of Venkateshwara Samachar, a Mumbai based daily, Mehta Lajjaram Sharma’s (1863–1931) contribution to Hindi is primarily in the field of journalism. However, he also wrote a small book called Jujhar Teja (1910), which he describes in its preface as ‘not novel’ but a story with ‘foundations in people’s memory’ that he made ‘intriguing’ by ‘adding some colours’.[3] Jujhar Teja recounts an oral legend from Rajasthan for the benefit of the emerging Hindi readership. This novel is not only an example of orality interacting with print, but perhaps one of the few non-sectarian historical novels from this period.

Brajnandan Sahay

Brajnandan Sahay (1874–?) was a lawyer by training and edited the Naagri Hiteshi Patrika from Arrah, Bihar. He also published an anthology of Vidyapati’s verses along with commentary and a short biography of the poet. Sahay mostly wrote social novels, but his Laalcheen (1916) is a noted historical novel from this period. It narrates the power struggle between Gyasuddin Bahmani of the Bahmani Sultanate in the Deccan and his Turkish slave Laalcheen. This novel is an important milestone in Hindi for it shows signs of innovation as it moves away from the magical world of historical novels that preceded it, focusses on character development instead of plot, and emphasises less on romance and sensuality.

These are some of the leading historical novelists in Hindi who dominated the Hindi literary scene in its early phase before a new generation of writers, such as Vrindavan Lal Verma and Acharya Chatursen Shastri, emerged in the 1930s. Translation and adaption from other literary traditions such as Bengali, Marathi and English evidently played an important role in the emergence of the historical novel in Hindi. However, an even more important role was played by literary monthlies and weeklies where these novels were published. As we have seen, writing for the early novelists in Hindi was not only a creative activity but also an entrepreneurial venture that aligned with serving the cause of the Modern Standard Hindi in the Khariboli dialect.

Notes

[1] The Hindi literary actors used this term for ‘self-fashioning’ often on the title page of their books. Hitaishi refers to the semantic field associated with words such as sympathiser or well-wisher, however, here it denotes a person who serves the cause of Hindi.

[2] See Dwivedi, ‘Pustak-Pariksha,’ 38–39.

[3] See Sharma, Jujhar Teja.

Bibliography

Sharma, Metha Lajjaram. Jujhar Teja. Lucknow: Ganga Pustakmala, 1928.

Dwivedi, Mahavir Prasad. ‘Pustak-Pariksha.’ Saraswati (January 1905): 38–39.