Introduction

The basis of the documentation of the Dalapathi system and insights into it have largely been through the experiences people have generously shared. In order to stay true to the source and provide context to insights, these photo narratives aim to offer an open interpretation of the memories they represent. The physicality or ‘materiality’ of photographs also translates the abstract representation of photographs as objects that exist in space and time (Batchens et al 2004a). The way these photographs are distributed, preserved or displayed, stresses on the object as a social and cultural artefact. Photographs become more than just their image content; they are social and cultural artefacts that create a view of a historical past.

Fig. 1: The original letter submitted to the DySP and found in the possession of Narsappa Dalapathi. The letter was laminated and kept with other personal documents relating to his work as a Dalapathi.

Letter to DySP

The letter was drafted by Narsappa Dalapathi in 1999, on behalf of the larger community of Dalapathis. A loose translation of the letter reads as:

'Because of the monsoon, there has been an increase in thefts in the villages. The Dalapathis feel helpless and scared for their life. Through this letter we are requesting provisions for a torch, raincoat and a small weapon. Since I (Narsappa) have been working for 24 years without any pay, some kind of salary be arranged for myself.'

This document not only speaks of a sense of community and unity among the Dalapathis but also about the leadership undertaken by Narsappa in a collective. He recounts being called to the SP office with 50–60 Dalapathis, before handing over the letter. Dalapathis were often called into the SP office, to be trained, for dissemination of information, to commend them for their work or just to make sure things were okay.

In 1999, the Dalapathis requested for a weapon to carry with them which they could use for their self defense as well as a torch battery. The SP asked them to hand over a letter to the DySP with the same requests. So they gave the request letter the next day and the police got back to them five to six days later with another meeting. On the sixth day, 30- 40 Dalapathis went to the SP office, but only 5-6 were given laathis and battery torches. The police said to the five Dalapathis who were given the laathis, ‘You are doing good work so take these two things.’ They also told the others who did not get the laathi and the battery, 'It's not that we don’t want to give it to you. But you should work like the other five, our police personnels have given us a report on these 5-6 Dalapathis. Our officers have seen them going on beats at 2-3 am. Even if it is dark, they still go, even if there are dogs chasing them. We have made a list of how all of you are doing your work, these 5-6 Dalapathis will be given this short laathi.'

Narsappa Dalapathi was one of the Dalapathis who received a battery torch and a laathi (a strong stick used as a walking stick). Below is a picture of a torch still in possession of the Dalapathi of Mallgapur village, Bidar.

Fig. 2: The battery torch found in possession of the Dalapathi of Mallgapur village, Bidar District

Panchayat election card

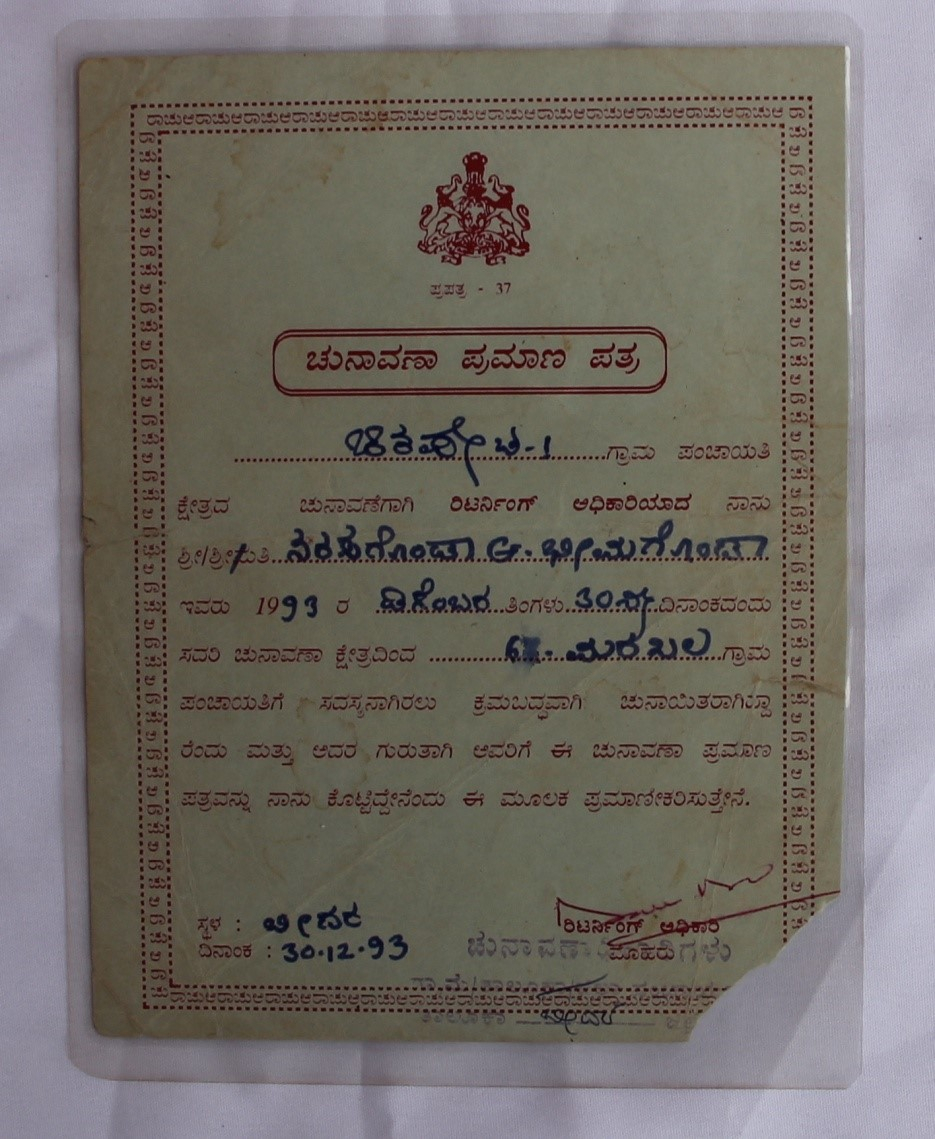

Fig. 3: Narsappa’s Panchayat membership ID, laminated

Under the Zila Panchayat Act, 1983, a panchayat was set up in Markhal which was an intermediate-level panchayat, called the Mandal panchayat. Gram panchayats at village level were introduced through the amendment of the act in 1993. The Mandal panchayat included panchayats of surrounding villages, one of which was Chikpet.

Narsappa Dalapathi doesn’t remember when he became member of the panchayat but says he had been a member for around 25 years. Since he had gained a lot of experience working with people in different villages and through his own his work as Dalapathi, the Panchayat asked him to become a member. They ensured votes and support, and encouraged him to stand for the elections. Narsappa recounts other incidents during the elections, giving insight into the political awareness and the development carried out in the village through his membership.

Narsappa was elected as representative of Chikpet in the Panchayat. He used his new position of authority towards the betterment of the village and people. He says he wanted to get the same kind of recognition he got as Dalapathi, for his new role as a panchayat member. He proactively advised the Gram panchayat on housing schemes, ensuring that these programs benefited the poor and was not misused. He also had street lights installed in the village. He provides an interesting account of how he got that done, laying emphasis on the confidence and privilege he gained through his role as Dalapathi. It started with him and possibly with the help of others picking up 40 steel poles lying in another village, waiting for installation. Following this he recalls:

'An officer from the Karnataka Electricity Board came one day, and he was having lunch, he said he asked him what the poles were doing in the village. I told him I took them and when threatened by him that he will take action against me, I told him to go book a case. I was confident because the SP supported me. Even the clerk in the KEB office told the officer he cannot book me in the case because I was close to the SP. So then they had to leave. They sat in the jeep and left.'

The next day, the light poles were installed by the KEB and the villagers. Narsappa describes the lamp poles with pride, 'You won’t find these kind of poles in the surrounding villages, its only in Chikpet. Heavy duty poles, very good quality.'

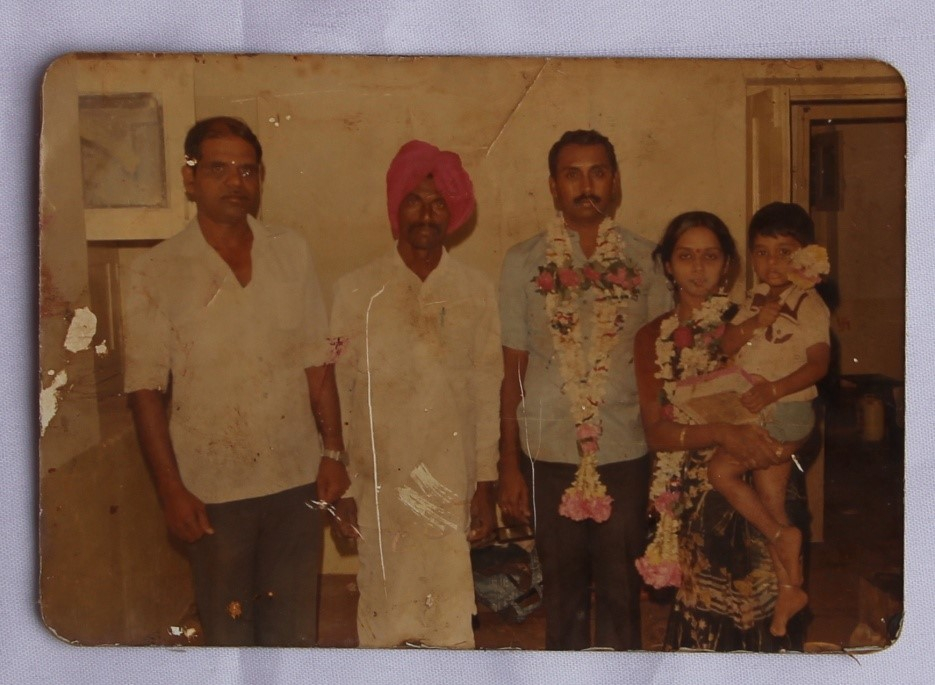

But Narsappa’s ambitions for street lights in Chikpet did not stop there. He ensured they had tubelights installed instead of bulbs, and for this he went to Veer Shetty Kushnoor, a minister of state for cooperatives in the Devraj Urs cabinet in 1978. He was successful in doing so and says, ‘people who would pass by, either by bus or other ways, they would look at the village and wonder how they have so many street lamps and they would compliment the people who got that done.’

Fig. 4: A framed picture of Narsappa (man in turban on the right) and Veershetty Kushnoor (centre with garlands around his neck) this picture was taken when Veershetty Kushnoor came to Bidar and was most likely being honored for being elected as the president of the All India State Cooperatives Bank Federation in 1976. The photo is not dated. This picture was found in possession of Narsappa Dalapathi.

He also emphasises on his principles while implementing these roles of leadership. He portrays an image of honesty, service and generosity. He also shows characteristics of ambition and strong leadership. Despite being uneducated, Narsappa was pragmatic and tactful, who did not shy away from taking bold steps that would improve the condition of his village and the villagers. The motivation for his service was in the form of respect from everyone around him.

Some of the other development works he lists out as part of his self-narrated legacy—the construction of an overhead water tank and borewell to resolve the water issues in the village. Also proposing to the District Commissioner to have a Ring Road being built around the city, and be also made to run adjacent to Chikpet. This helped drive up the prices of land situated near the Ring Road.

Fig. 5: The overhead water tank in Chickpet. Picture taken by author.

Photo with Chickpet Development Commission

Fig. 6

The State Bank of Hyderabad adopted Chikpet village and under this programme, a school was built in the village. The move was initiated by a college professor in Bidar and the State Bank of Hyderabad, to provide accessible schooling to the children of the village. Narsappa says that the school started with one room, and has now grown to 1000 rooms (figuratively speaking). This photograph is the last photograph attached inside the hard shell of a photo album of different public events Narsappa has been a part of. This picture is not dated and the only photograph in the album that is not contained in a plastic sleeve. In the photograph, Narsappa is on the extreme right, wearing a pink turban. The group of men in the centre of the photograph are the officials from the State Bank of Hyderabad. The board behind them reads ‘Chickpet adopted by State Bank of Hyderabad’.

Photograph with S.K. Venugopal and B.M. Padmanainah

Narsappa’s photo album also consists of many photographs of him shaking hands with, or standing next to, various officials and members of the Police. These photos range from the 1970s to nearly present-day, with the most recent one being from 2016. He speaks of these men and women with a note of admiration and pride, and also speaks of how the same was reciprocated by the officials towards him. These pictures also imply the presence and importance of social connections made through the ‘Dalapathi’ title. It opened up opportunities for negotiation between institutional authority and personal goodwill. These negotiations eventually helped build a legacy of his own.

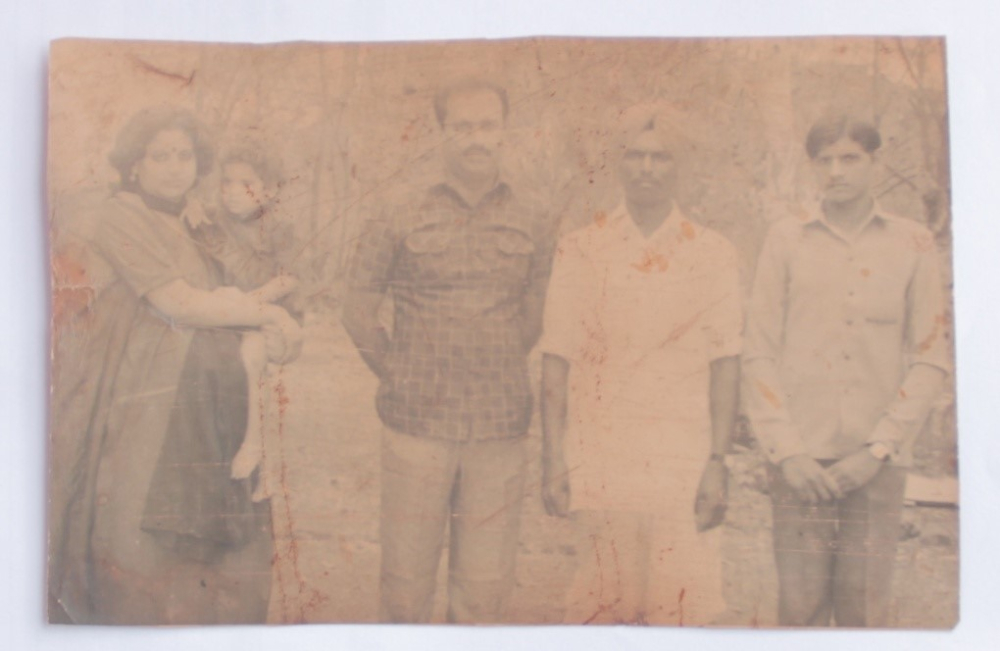

Fig. 7: Narsappa Dalapathi (2nd from right) with DySP S.K Venugopal (3rd from right) and S.K Venugopal’s wife and daughter. The person on the extreme right was a police press photographer

The narrative that emerged from the photograph of Narsappa with S.K. Venugopal and his family, spoke of trust and co-dependency between the police and Narsappa Dalapathi.

Once, there was a thief named Muriki Madale who had stolen guns from a court. There was a rumour that the thieves and the police were helping each other and that is how crimes like guns getting stolen from the court were taking place and everyone would question, that such crimes cannot happen without the involvement of the police. It was not good for the police departmen, they were feeling insulted, and everyone was talking about that.

The police had become cautious and approached Dalapathi, asking him to keep a watch for unusual activity, or for anyone carrying arms. Narsappa found the thieves in a nearby village called Maski by chance, and immediately went to the Police headquarters to report them.

'I went in to the headquarters and S.K, Venugopal called me into his office. There was a gunman there. I looked at the gunman and was wondering if I should tell in front of him because there is a possibility that he is involved with the thieves. So S.K. Venugopal saw my face and understood what was going on in my mind. He asked the gunman to fetch a file and sent him out of the office.'

The police took action on Narsappa’s word and the gang of robbers were caught. Narsappa reinforces his motivations and ideals of service in his own words:

"M.K. Srivastav and Venugopal respect me a lot. I did not just do Dalapathis work, I worked for the village, was a member of the panchayat for 5 years, and did not take money from anyone. I am a man of principles and do not do things for my own benefit. My aim was that my name should be known to everyone in Bidar zilla. If you want recognition you have to do good work, not get greedy and not do it for money, even today I do things the same way".

Narsappa also used these connections to build a rapport of trust and dependability with the villagers, his friends and anybody who approached him for help. As a Dalapathi he often resolved disputes between villagers fighting over land and also intervened in cases of domestic violence. The presence of societal norms and beliefs influence his decisions, and also tell us the impact of this system on the culturally vulnerable in the village. Narsappa’s son, Mallapa, speaks of these principles present in Narsappa, and his role in cases of domestic violence.

"If there was violence in the house, the lady just had to come to my father. He would tell the husband just once, that if you don’t correct your ways now, and if I get another complaint, I will make sure to leave you in a condition that you will never be able to raise your hand! Until now, no one in the village gets drunk and beats their wife. Until now. My father really controlled these cases very well."

He remembers one such case when a friend approached him with the disturbing and unfortunate news that his daughter had been burnt alive by her in-laws in Gulbarga. Narsappa says that his friend would often come to him and worry about his daughter in Gulbarga, because he knew that they were torturing her. Narsappa wanted to help his friend, and in this case, he took advantage of his strong network and presence in the police and approached the SP in Gulbarga.

Fig. 8: Narsappa (in pink turban) with the then DySP of Bidar, B.M. Padmanaiah on the right, along with his wife and child. Identity of man on left is unknown.

One of the finest officers who was in Bidar, Padmanaiah was transferred to Bangalore from Bidar. Later, Narsappa found out he was posted in Gulbarga. When he got to know DSP Padmanaiah was in Gulbarga, Narsappa wanted to visit him.

Narsappa took his friend to Gulbarga, and successfully met the DSP. Narsappa once again negotiated with institutional authority, and used his connections towards ensuring justice for his friend and his daughter. This is the manner in which he narrates highlights this incident:

'We went to the DSP’s office, where there was a lady who asked where we were from. We said we were from Bidar and had to meet the DSP regarding the case. So she wrote my name on a piece of paper and told us that only one person can go inside and talk. But I insisted that all 4 -5 members be let in as they all needed to talk to him. She said that as per the rules they could allow only one person at a time. I told her to tell the SP, that the Dalapathi of Chikpet has come with a few other people. If he says he can’t meet with all of us then we will go back. We meet him as a group or we will go back to Bidar.' Then she asked me if I know the DSP personally. I said yes. She asked me the SP’s name and I told her. ‘You know him personally?’ ‘Yes I know him personally.’ So I had to wait for a couple of hours before I finally got to meet him. When we met, he asked me what the meeting was about. I said, ‘How could such a thing happen in your jurisdiction?’ ‘What are you talking about?’ After I told him what happened, he asked me to wait for 5 minutes, called the Sub Inspector and Circle Inspector and, with them, immediately went and arrested the deceased girl’s husband and his family.'

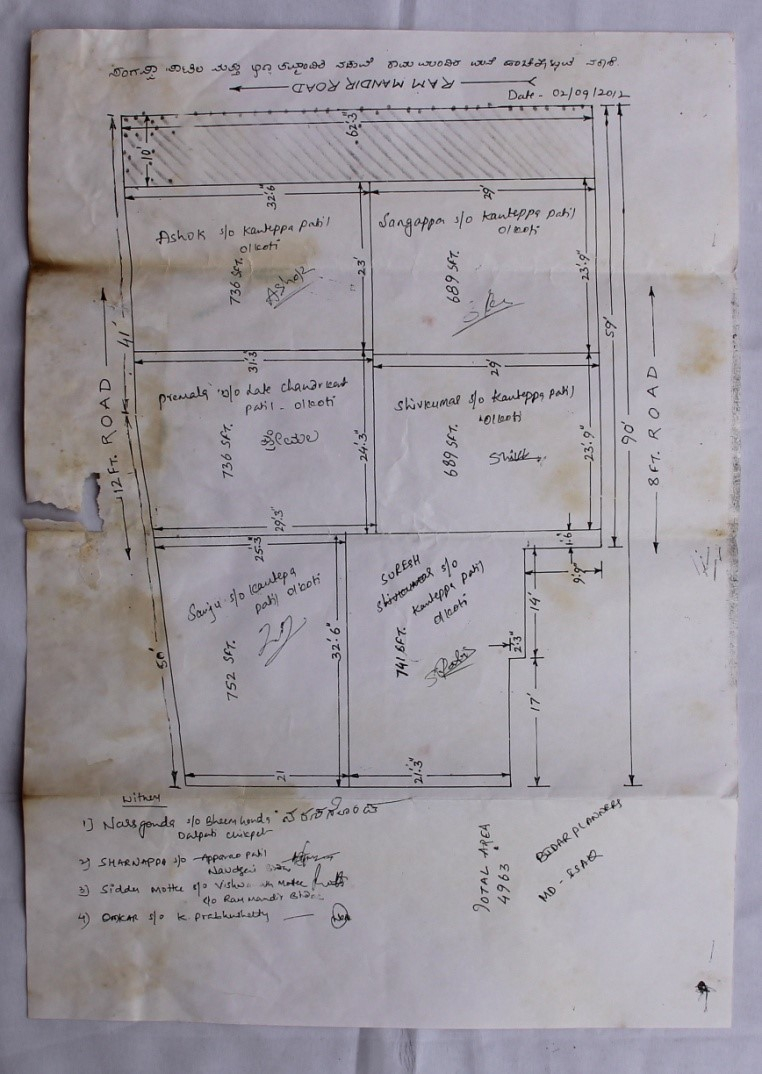

Hand drawn map for a land dispute case

There are some documents that are literal representations of the work he has done, and the kind of disputes he has helped resolve. Land disputes and land grabbing cases are common occurrences in villages, where land is a major asset. The villagers would often prefer to come to the Dalapathi, rather than go to the police. The police also encouraged villagers to go to the Dalapathi in such matters and advise them against legal action. Narsappa shares one such dispute through a hand drawn map he preserved as evidence of the decision made and agreed upon.

Fig. 9: Map drawn out by a lawyer that helped Narsappa section the property between the conflicting parties.

Once there was a dispute between Sangappa Walkoti and his Patil brothers. They were 6-7 brothers. Their house was in Ram Mandir. They had had 3-4 Panchayat hearings earlier in the presence of people from surrounding villages. Every time it would end in a fist fight and people who were present to resolve the issue would leave because of the fights. Someone recommended Narsappa's name, trusting him to resolve the dispute. Narsappa says, 'They called me and announced a date. I don’t remember the date. I went to Walkoti to look at the house and the property. They asked me to distribute the property among the six brothers. Again the quarrel began I asked the youngest brother to sit next to the door in a corner and said why have you called us if you had to start a fight over the issue. After warning them we got them to sit separately at different places in the house. Then I asked where is their father. They replied saying he was in the agricultural field I asked them to bring him. How can the property be distributed in absence of the elder of the family. Tomorrow if he disagrees the issue will persist. He was brought home. I asked him, 'Patil Sahib, your sons have approached us to resolve the dispute over the share in this property. I am here with 5-6 elders to look into the dispute. What do you think?' He said, 'Please split the property, we are fed up of the quarrel between the brothers.' I told the brothers not to fight with each other and taking the issue to the court would be of no use. We split the property in two large chunks.Three shares in one part and three in the other.'

Shailendra Dalapathi’s newspaper clippings

Public memory also becomes an artefact of personal history. Storing newspaper clippings becomes a subversive act of removing an event and a piece of writing from the larger narrative of a newspaper and associating one’s own personal values to it. Shailendra Dalapathi of Chitguppa Taluk, shares a couple of newspaper clippings about Police Patels and the Dalapathi Union. Once clipped, these clippings do not present any information about when it was written and for which publication, but only the article itself. When asked why he keeps these newspaper clippings, he says,

'There is a lot of respect for Dalapathi and Police Patels...whatever is written in the paper. If I am here tomorrow or not, the newspaper cuttings will help keep the memory alive for the next person who comes along. Like you came today, so I could show you. I can’t remember everything anymore, but at least this writing will remain after I am gone. Keeping this in mind I kept all these cuttings.'

Fig. 10: The newspaper article is about the Police Patels being sanctioned pensions of Rs 300, for their service during the freedom struggle. The headline reads ‘Pension for Patils and Patels who were part of the freedom movement.'

Conclusion

These photo narratives provide a small glimpse of the lived experiences of Narsappa Dalapathi. Certain actions, decisions and statements hint towards his personal capacities and cultural beliefs.

Material memory is also used to elicit interviews surrounding photographs and artefacts. Although Narsappa’s memory fails to provide information that conventionally authenticates an event, such as date, time etc, his material memory constructs a reality experienced by him, and further corroborates the presence of subjective nuances in the Dalapathi system. Narsappa Dalapathi used this position of authority to break caste and class barriers, which were also catalysed by the political and social reforms of the 70s. Narsappa continues to be called Narsappa Dalapathi, and despite the repeal of the act in 2004, the respect, goodwill and recognition he gained, he has retained his title of the Dalapathi in the village. Now, as Narsappa narrates his own legacy, it would be interesting to inquire into the longevity of this legacy in modern India, with its ever changing forms of storytelling and collective memory.

References

Batchen, Geoffrey. 2004. Ere the substance fade: photography and hair jewellery. In Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, edited by Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart, 32-47. London: Routledge Press.

Bate, David. 2010. The Memory of Photography. Photographies 3(2):243–257.

Further readings

Banks, Vokes. Introduction: Anthropology, Photography and the Archive, History and Anthropology, Vol. 21, no. 4 (December 2010):337–49.

Becker, Howard S. ‘Visual sociology, documentary photography, and photojournalism: It's (almost) all a matter of Context.’ Visual Sociology 10(2008):1–2, 5–14.

Keightley, Pickering. ‘Technologies of memory: Practices of remembering in analogue and digital photography.’ New Media Society 16 (2014): 576