Nuances of the system

Since there is little documentation available on the Dalapathi system as well as the people and communities involved, the act of collecting memories becomes a way to reconstruct a sense of the past and its relationship with the present. These memories serve as personal legacies of pivotal events, influenced by the political and social climate of the time. Memories, both collective and personal, resist correction by others. Everyone who shares a communal legacy must accept some agreed upon notion of its nature. But each one treats that corporate bequest as his own. Like personal memory, it is valued for being opaque to outsiders (Lowenthal 1997). Personal legacies take shape through the individual’s sense of morality, truth and ethics, which in turn are shaped by one’s own lived experiences. Using personal narratives to build an objective picture of the past becomes challenging, but it must be remembered that the personal experience is also anchored to a collective truth. The creation of these legacies comprises actions rooted in the desire for social upliftment, honour and public memory. Furthermore, in the absence of documentation, the narration and form of these legacies also provide insight into the very act and rationale of preserving memories themselves.

To understand the social implications of a title of authority such as the Dalapathi, it helps to understand the social and economic elements that influence the village community. ‘...[A] village is never socially isolated, its ties are coextensive with its caste relationships (Srinivasan 1956).' Despite the cultural differences of caste and religion, there is a sense of shared community feeling in the village that has always allowed for cooperation and administration of local affairs. Post-Independence, the Indian village was also no longer politically isolated; this subsequently influenced the social structures present in villages.

Karnataka was under the leadership of Chief Minister Devaraj Urs between 1972 and 1980. He nominated many individuals from backward castes, tribes and other minorities, to contest for the elections in 1972; Urs' party swept the polls, and he became Chief Minister. In the formation of his ministry, Urs was careful to choose as many as he could from the non-dominant castes (Srinivas 1984). The socialist agenda of the ruling Congress government had an effect on the social mobility in rural Karnataka, and it led to the upliftment of certain non-dominant castes, the dominant castes being the vokkaligas (peasants) and the Lingayat community (Srinivas 1959). There was still some criticism over the actual impact of these reforms on the stronghold of dominant communities.

There is an opinion harboured by some well-known scholars that the Devaraj Urs' regime in the 1970s was conspicuous for its most effective assault on the Lingayat-Vokkaliga dominance, and more important, for the ascendancy of the numerically minor, and socially and economically disadvantaged communities in Karnataka. This requires a critical review. As our data show, the non-dominant communities made some gains during Urs' regime. More important was their acquisition at the level of consciousness and confidence (Ray 1987).

Many programmes were implemented by the government for the eradication of poverty and for the upliftment of the backward castes. A debt relief act was passed which at one stroke liquidated the debts of those earning less than Rs. 4,800 per year; a housing programme styled the People's Housing Scheme was started which enabled individuals to build their own 'pucca', though simple, houses with the aid of a government subsidy: a pension scheme of Rs. 40 per month for those above 60 years of age, and the destitute, was initiated and proved popular, an Employment Assurance Scheme was begun under which landless labourers and others were assured paid employment for 10 days during slack periods in agriculture; and finally, co-operative societies were restructured with a view to benefiting poorer members (Srinivas 1984).

The critique that the economic conditions of non-dominant communities did not change radically despite the attempts at reformation through policies still stands; however, there has been some impact and it ‘helped the new entrants from the non-dominant communities to leadership roles in the Karnataka politics to acquire new heights of power and privilege.' (Ray 1987).

The Dalapathi—Individual and the community

The title of the Dalapathi was one of these leadership roles that was offered under the Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act, 1964. The implications of the ongoing social reformations were also seen in Chikpet[i], a small village/hamlet situated 3 km from the outskirts of Bidar. Narsa Gonda was born in 1936 and brought up in Chikpet, one of the 699 villages of Bidar. Orphaned at the age of three, he was raised by his grandmother, Shivamma, as the only child. Narsappa quit his education after 4th standard, as they could no longer afford it, and helped his grandmother in their fields. Narsappa, like his family members, was an agriculturist, belonging to the ‘Gonda’ or ‘Kurbur’ community, traditionally a community of goat herders from Rampura. According to Narsappa, at the time of his appointment as Dalapathi, Chikpet consisted mostly of Dalits with a few houses belonging to families from the Muslim, Christian and Lingayat communities.

Looking at M.N. Srinivas’s study of dominant caste systems in a village in Rampur, a comparison can be made to briefly understand the workings of caste and other social factors that influenced the impact of the local authority in the village. ‘A study of the locally dominant caste and the kind of dominance it enjoys is essential to the understanding of rural society in India. Numerical strength, economic and political power, ritual status, and Western education and occupations, are the most important elements of dominance (Srinivas 1959). The dominance of a certain caste or community dictates the extent and nature of compliance of the village community towards the decision of an individual representing authority. Crime was also dependent on the economic conditions and the scale of poverty present in the particular village and in neighbouring villages as well.

'Here in Chikpet, the Dalit community has the largest number of residents, followed by Christians. There were 8-10 houses of the Lingayat community and only one house was ours i.e. of Gonda (kurbur) community. During that time there were no concrete homes, only huts, and later concrete houses were built. Everyone was poor back then. During that time, the monsoon rain was heavy and the crops would get destroyed and there was the menace of thieves too. They would even steal oxen from outside the villagers’ houses and everyone was scared of thieves. They would not venture out of their homes; this was the situation back then.' (Narsappa Dalapathi, pers. comm. 2017)

Communities and villages also share a sense of ethics that are rooted in their shared cultural beliefs. These ethics become the basis of decision-making and of the acceptance of these decisions. Narsappa shares many anecdotes where he was called in by villagers to resolve land disputes, inside and outside the village. Villagers would prefer to come to him rather than go to the police directly. In most cases, the parties involved would heed his advice and the dispute would be resolved without it ever reaching the police headquarters. Drawing another comparison from M.N. Srinivas’s study of dominant castes in Rampura, he too writes about the tendency of villagers to avoid the court of law.

It may be mentioned that a good deal of what goes on in a law court does not make sense to villagers; they know that a clever lawyer has to be hired and that when a man loses in a lower court he can make an appeal to a higher court. When a man loses in a government law court, it does not mean that he has done wrong or that he loses face with his fellow villagers, but only that his lawyer is not clever enough or that he is not lucky. Villagers know that a man who has a right to a thing, may lose it in a law court and that a man who has no right to it may win it. This contrasts with the decisions of a village court, which have an ethical connotation (Srinivas 1959).

The selection of a Dalapathi

The Dalapathi literally translates to ‘dal’ meaning community, and ‘pathi’ or head in Kannada. The Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act infers power to the superintendent of police (SP) to appoint a member of the Village Defence Party as he deems fit. Narsappa Dalapathi recalls his selection as a democratic leader by the villagers but under the supervision of the deputy superintendent of police (DSP).

'An announcement was made in the village regarding this, to assemble at 9 am in the village. The next morning, the villagers were asked about Police Patel Sharanppa Gundappa. And in front of everyone, the DSP asked them who was to be made the next Dalapati. And then the villagers suggested my name saying that only Narsappa can be the one as he is fearless and roams around at night too. Even the Police Patel agreed to my becoming a Dalapathi saying I am a good man and DSP sir asked his opinion about me. Then the DSP told me to take care of the village and to avoid any fights that might happen. He also told me that there will be thieves and advised me not to roam alone but take a few men along with me on my nightly trips. This is how I was made Dalapati.' (Narsappa Dalapathi, pers. comm. 2017)

Although the powers of the Police Patel were officially dissolved in 1963, their position and privilege still remained. There was no immediate replacement for the Police Patel until the appointment of the Dalapathis in the mid-1970s, and most often the Police Patels continued to provide consultation to villagers in the cases of disputes and petty matters. With the formal appointment of Dalapathis in the mid-1970s, Police Patels were also selected, albeit maintaining the democratic nature of the selection. In some cases, Police Patels were intentionally not considered, despite their interest.

But overall, the transition into the Dalapathi system is so far known to be without any conflicts between the Dalapathi and the Police Patel in the same village. Apart from being a police informant, the Dalapathi was expected to provide lodging and food to constables visiting on their weekly/fortnightly beats, maintain a record of the births and deaths in the village, and also maintain order during public programmes and elections. There was also a relationship of respect between the police and the Dalapathis.[ii] Gurusidappa, a retired assistant sub-inspector, was appointed as village beat constable in 1977. He shares an anecdote that exhibits the cooperation and trust between him and the Dalapathi of Asthur village in Bidar, as well as the particular tensions that existed in different villages:

'To ensure there are no thefts in our beat was our responsibility; that there be no communal fights, and if anything looks suspicious, we have to report it in advance. To send for the police, and call for officers, it was like that. During that time, in Ashtur village there used to be more of communal disturbances, including those between Dalits and non-Dalits and between upper castes and non-Dalits. So we used to camp in the village, sleep in the Dalit homes, become friends with them, try to resolve their problems and discourage fighting.

During Ughadi, there would be a procession, and both the communities used to cross paths and cause a violent disruption. So what I did to control was this: in the evening around 4 o'clock, we got the carpenter in the village to make a ‘Gilli Danda’ with wood. We would then identify the troublemakers, who would throw stones and cause fights. We did not let them know that we were doing this to distract them. There is a Dargah of Allamprabhu, where both Hindu and Muslims would come for pilgrimage once a year. There is a big field in front of it. We organised a game there and made sure it went on for 3-4 hours. Lots of people came to see us play since we were also in uniform. People liked to see policemen in uniform during those days. So then we told the Dalapathi to begin the procession, while we continue to play here, you go. The Dalapathi was my ally. So this is how we used to avoid communal problems.

They respected us a lot during that time, till 1980–82, the villagers respected the police a lot. Mostly till 1985. Then later people started leaving the village and went to the city and the town, and the town culture crept into the village. So the village culture came down.' (Gurusidappa, pers. comm. 2017)

This change in the attitude of the village residents may be attributed to the increasing urbanisation and politicisation of villages. As 1983 saw the introduction of the Zilla Panchayat Act, it resulted in a decentralised local government, with a District Panchayat at the district level and in their 1993 amendment, also Gram Panchayats at local levels. Under the 1983 Act, the parishad has extensive planning, administering and monitoring powers in development. The most important is its planning authority. It was not uncommon to find Dalapathis with experience to become members of the Gram Panchayat, presidents of the village cooperative bank, members of Land Tribunals, etc.

Powers, duties and rights of the Dalapathi

In Chikpet, Narsappa Dalapathi became a Panchayat member and was the single most member representing the Gram Panchayat in Markhal village for 25 years. The goodwill he collected due to his work as a Dalapathi also helped further his political standing and involvement in the development activities of the village, through the Panchayat. The Panchayat assured support and votes if he stood for the elections, and he says that it was because the Panchayat knew that he had a lot of experience working with people in different villages and his own. However, retired DGP and ex-SP, M.K. Srivastav, also points to the increased politicisation of the village as a reason for the eventual dissolution of the Dalapathi system. ‘Villages were already divided on the basis of caste, class, religion and now also political affiliations.’

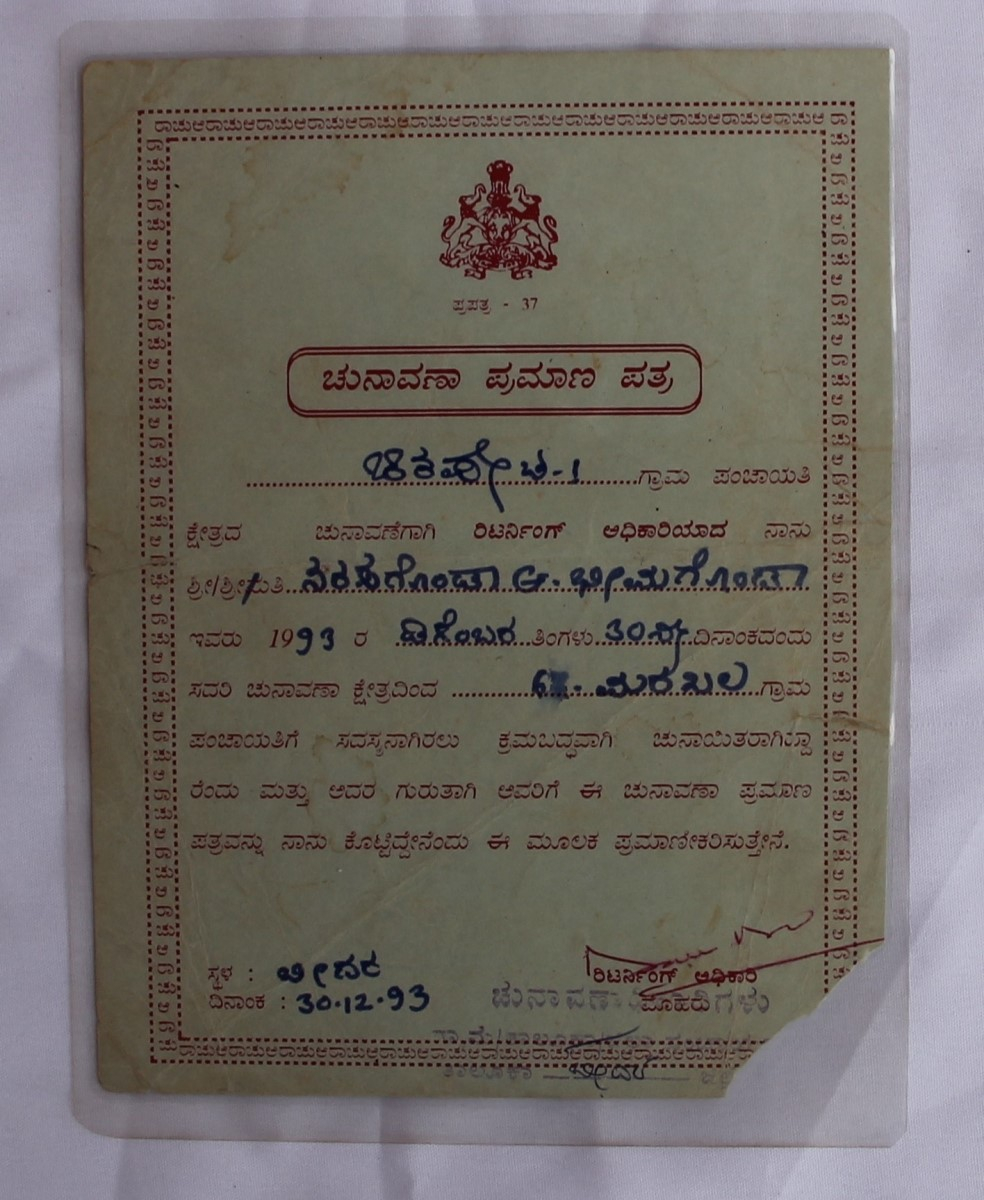

Fig 1. Narsappa’s Panchayat membership ID

Unlike the Dalapathi, Police Patels were paid public servants that received a monthly stipend for their ‘services’. With the transition into the Village Defence Party system, its members perhaps felt a sense of apathy towards their function as Dalapathi, because they never saw the role as that solely of goodwill and community service. Reciprocity was expected in the form of remuneration. Annarao Patil of Chitta village, located approximately 5 km from the city centre, was appointed as Dalapathi in 1978.

'My name is Annarao Tande Basappa Patil of Chitta, Bidar Taluk. I was selected as Dalapathi in 1978. Before me, my father used to do this. After he died, I continued in his footsteps. After that, there was no help from the police, they just came to us to get their work done. We are like ‘use and throw’...basically nothing. There was no help from the police, they just took advantage of us when there was a murder…if there was an accident or a murder, they came to do their investigation, took our signature and that’s it.' (Annarao Patil, pers. comm. 2017)

His resentment for not being compensated for his Dalapathi status was shared by many and the increased political awareness resulted in them congregating to form the ‘Dalapathi Union’ in various districts and taluks. Several writ petitions were filed by the Dalapathi Union to the High Court for an honorarium to be offered. Judgements were passed in their favour but the compensation is yet to reach many. The Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act, 1964, also lists the powers, liabilities, protection and privileges of the Village Defence Party as the same as those of a police officer.[iii] These rights and duties were disseminated to the Dalapathis through a booklet called the ‘Dalapathi Rule Book’ published by the Bidar police department, in Kannada. Their rights and duties were also understood to be the same as those of Police Patels who were paid public servants, and of the police themselves. This was also the basis on which they justified their demand for remuneration and subsequently formed the Dalapathi Union.

In an interview with Vijay Kumar Dalapathi of Chitguppa, he mentions the same and elaborates on his understanding of the Dalapathi and Police Patel role.

'The Dalapathis told the government that you should give the same compensation to us as you give to the police constables. We have also worked night and day, so you should give us the same payment, but instead, the government banned it. There are cases still going on, there is a Dalapathi Union, there is a case from the union still ongoing. If there is a fight in the village, we try to convince them to abide by the law, you are not going to get anything out of fighting; try to settle the matter between yourselves, but of course with the advice of the police… so this helps stop any cases from being filed, and if there can be a settlement made where everyone is happy then there is no need to make it into a case and get into legal procedures.' (Vijay Kumar Dalapathi, Chitguppa, pers. comm. 2017)

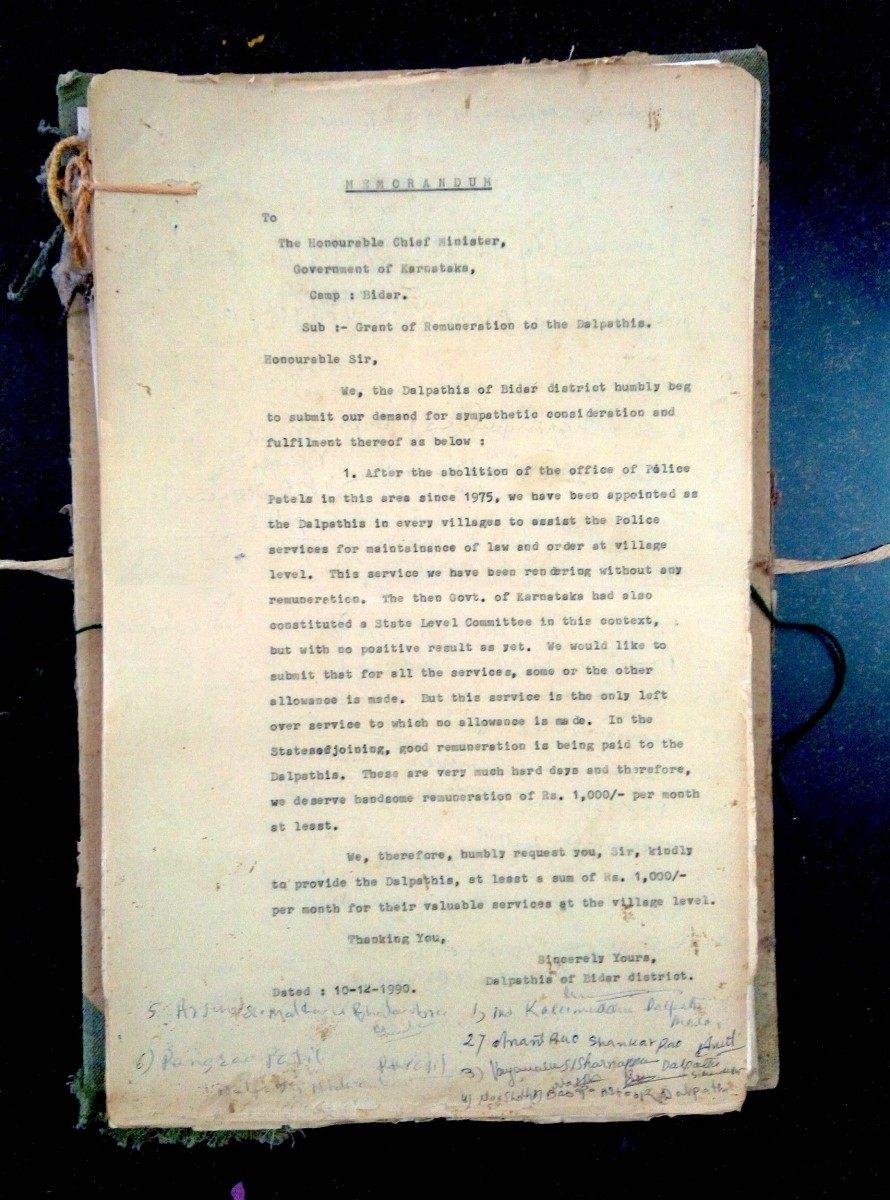

Fig 2. A Memorandum typed and sent to the Chief Minister in 1990 on behalf of the Dalapathis of Bidar, requesting a fair honorarium for their services. A mention of the abolishment of the Police Patel is made perhaps because the roles of the Police Patel and that of a Dalapathi are seen as the same, but remuneration and pension were offered only to the former.

The presence of women is also minimal in the system; there have so far been no instances of women being appointed as Dalapathis. Perhaps this is also reflective of the non-involvement of women in the Zilla Panchayat, despite a 33.3 per cent reservation for women. Further inquiry is required to understand the impact of the Dalapathi system on women, especially in cases of resolving domestic disputes and gender-based violence.

Although the Dalapathi system was implemented through a legal act, there was also a creation of values through the system. Social connections were made at the village and institutional-levels. These relationships remained despite the repeal of the act and the dissolution of their powers. In Chitguppa, previously a village under Humnabad Taluk in Bidar, Vijay Kumar Dalapathi was appointed as Dalapathi in 2004. His case is unique as he was appointed Dalapathi after the repealing of the Village Defence Parties Act. His retelling also gives insight into the involvement and motivations of other village authorities in the selection of a Dalapathi.

'My name is Vijay Kumar, my father’s name is Chandrappa, surname Patankar, I live in Chitguppa, Taluk Humnabad, district Bidar. I am 41 years old. My work is social work, meaning that I work as a Dalapathi selected by the town, which was banned by the government. In 2004, I was appointed the Dalapathi, and I have been in service for almost 14–15 years. So the Dalapathi is like the Police Patel, a friend of the police, someone who works in favour of the law. If any criminal is on the run, and I have any information about him, I have to tell the police There are also times when there is no information....Before me, the Dalapathi was Raju Padma, he was given a government certificate; so when he died, the police department told me—the then officer-in-charge, about 15 years ago—he told me the Dalapathi seat is empty, you work well with the police, the work is good, you have knowledge, so you take this up.

I asked what the procedure was. They said that the important people of the village such as the TMC members, all members from different communities, two people from each community, you have to get their signature and seal, declaring that they approve of me and that I should take up the role. So accordingly I prepared the documents, I gave all the required documents to the SP office, got the signature of the circle inspector, the DSP and got this done myself. So the SP of the time, I don’t remember who, he told me that now there is a ban, so I cannot give you a certificate, you would have to continue to work without it. When the government lifts the ban, I will give you the certificate. So I said okay, and since then whenever the police ask for a favour, I do it.' (Vijay Kumar Dalapathi, Chitguppa, pers. comm. 2017)

Personal narratives in a formal system

It may seem that the Dalapathis were only driven by reciprocity in remuneration but that is not entirely true. The recognition, honour and pride that came with the respect of the villagers were sources of motivation for Dalapathis to continue their service towards the police and the village community. Many awards were also handed out to Dalapathis, and they were frequently recognized for their work through various rallies. As each village existed in varied socio-economic conditions, the Dalapathi system was openly interpreted and implemented by the individual in authority. Personal histories, experiences and capacities also dictated how and why the role was taken on. For example, upon knowing that Narsappa Dalapathi’s father was killed by a group of robbers when he was three years old, a connection can be made to his personal aspirations of making the village a safer place.

'No, I did not get scared! I was selected by all the villagers because of that. I took it very seriously. Other villagers also said, don’t go outside, someone might attack you with stones. Why are you going? There are too many thieves. But I was not scared. I was stubborn, I wanted to catch thieves. To take them to town and send them to jail and not let this happen in the village.' (Narsappa Dalapathi, pers. comm. 2017)

Examining these personal narratives also becomes a subjective exercise. Each village presents a unique case; hence the success, failure or workings of the system cannot be documented as a single narrative. Decisions made over disputes, their reasoning and the retelling of these incidents provide insight into the spiritual leanings and ideologies of an individual and the influence it has on their sense of morality. As official documentation available is minimal, examining personal narratives help derive a more nuanced understanding of a formal system. Oral histories and memories give insight into the people involved and prevent a homogenised view of the past.

Notes

[i] According to the 2011 census, the current population of Chikpet is 1275. It is located 3 km from the outskirts of the city and falls under the Bidar Taluk jurisdiction.

[ii] Information gathered from interviews with Dalapathis in Bidar district.

[iii] The KVDP Act, 1964, lists the below as the powers, protection and control of VDP members: (1) Every member of the Village Defence Party shall, when called out for duty have the same powers, liabilities, privileges and protection as the police officers appointed under the [Karnataka Police Act, 1964]. (2) No prosecution shall be instituted against a member of the Village Defence Party in respect of anything done or purporting to be done in the exercise of his power or the discharge of his functions or duties as such member, except with the previous sanction of the superintendent.

References

Lowenthal, David. 1997. ‘History and Memory.’ In The Public Historian 19(2).

Ray, Kumpatla. 1987. ‘Zilla Parishad Presidents in Karnataka: Their Social Background and Implications for Development.’ In Economic and Political Weekly 22(42/43).

Srinivasan, M.N. 1956. ‘Village Government in India.’ In The Far Eastern Quarterly Vol. XV.

———. 1959. ‘The Dominant Caste in Rampura.’ In The American Anthropologist 61(1):1-16.

Srinivas, Panini. 1984. ‘Politics and Society in Karnataka.’ Economic and Political Weekly 19 (2).

Further readings

Atal, Y. ‘A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of Caste.’ Sociological Bulletin 16, no. 2 (September 1967):20–38