This article attempts to follow the timeline and origins of the 'Police Patel system' and trace its transition to the Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act, 1964. It also tries to place the system in context of the changing political and social climate in South India and Karnataka from pre-independent to post-independent India. The study is situated in Bidar, North Karnataka, as part of the Bidar Police Museum and Heritage Museum.[i] The paper also, based on a study of personal and public artefacts and interviews, aims to understand the implications of the 'Dalapathi system' (dalapathi meaning village headman) from the community’s perspective, its effects on village society and the extent of social mobility it provided to non-dominant and underprivileged communities.

The police and the village administration

The creation of police forces in colonial India was to exercise control over the state, to become the eyes and ears of the regime and to suppress disturbances. The police in independent India is a product of the police in the colonial state, and is based on the same rationale as that of the colonial police. Bayley (1971) critiques the police in ‘contemporary’ India on the persistence of certain behaviour patterns and philosophy; he says, 'the primary function of the police continues to be containment of trouble once it occurs whether it be mob violence or individual criminal activity...from the citizen's point of view, the police are largely a passive force, difficult to energise, bureaucratic in working, impersonal and offhanded in operations.'

With a history of traditional and community-oriented police practices in India, the police in modern India has had different implications in rural India. Understanding the basic structure of village administration as well as the nature of life in villages becomes pertinent to understanding the history and context of its policing system. The Indian village can be broadly explained as settlements or scattered homes with socially and culturally diverse communities, largely characterised by agrarian economies. Before the creation of the Indian union, the revenue village or administration differed from the residential one, which comprised 'a central residential village, a few adjacent hamlets and constitutes the basic territorial unit for the administration of the country. Its officials -- a headman, an accountant and a watchman -- formed the lowest rung in the state bureaucracy' (Srinivasan 1956). These offices were held by the same families from generation to generation, and they were appointed and held responsible to the Nizam.

The village headman, official or watchman can also be traced back to pre-colonial India. Prior to British colonisation, 'Feudal society did not need a police constabulary. Towns were small and the manorial system closely regulated the life of the serf. Though the king exercised little direct control over his subjects, the feudal lord, acting through his personal retainers and village officials, held the reins of social control in his locality' (Arnold 1976).

Under the control of these feudal lords, villages in India were self-sufficient and this included independence in managing and preventing crime. Since ancient times, in India, village officers have been appointed for the purpose of preventing crime. Anupam Sharma (2004) talks about the different police roles present during the Mauryan period in 310 BCE as well as the influence of the Arthashastra of Kautilya on modern policing.

Village officers have had their own colloquial names such as police patel, maali patel, patwari, talaiyari, etc. The police patels and machkuris under them were appointed under the jagir and paiyga administration and were grassroots village officers, their function evolving from supervising tax collection to maintaining law and order in the villages. Whereas mali patels and patwaris maintained land records and collected land revenue; they were appointed to serve the best interests of the zamindars and jagirdars, as their bounty was also dependent on their loyalty and obedience towards them. These jagirdars and paiygas were large landholders and ultimate sources of power in the village, and the origins of village officers can be traced back to the origins of these feudal administrative systems (Eashvaraiah 1985).

Village policing before and after Independence

As the Deccan was a subsidiary alliance of the British, and the Nizam continued to hold control over the princely state of Hyderabad, a separate state police was appointed under the Nizam regime. This force was called the Nizam police and was expected to control law and order situations in areas directly under the Nizam’s rule. The police patels also acted as informants to the Nizam State Police, and were expected to send daily reports to the nearest police outpost of the village. There was also a lack of intervention from the British administration in these grassroots systems, although attempts had been made to control these forces. 'The Madras police failed to live up to the expectations of its founders. The attempt to interlock the constabulary with the villages through village inspectors was soon abandoned as impractical and it proved impossible to maintain the constables' (Arnold 1976).

One of the major setbacks for the colonial police was the lack of a sizeable police force as compared to the rural population. This implied the lack of interest on part of the colonial regime in village society and 'policemen were unwelcome strangers and frequently their intervention was at the request of a local landlord, who used the police to collect his rent or opposition to his supremacy' (Arnold 1976). The local landlord was represented by the maali patel and police patel; consequently, fear and intimidation were the general attitude towards the police, despite the Deccan being a subsidiary British alliance.

The Police Patel/Patwari system was also ridden with atrocities and deemed ‘inappropriate’ for new democratic India. The receiving end of this corruption and abuse of power would be the people living in the villages under the surveillance of the police patels. With the Hyderabad Abolition Act, 1950, the jagirdari tenures were abolished but with no change in its administrative set up at the village level. All the reform did was transfer revenue rights to the government.

Similarly, with the Land Tenancy Act, 1956, the preparation of land records remained in the hands of the patwaris and maali patels. No new village officials were hired to carry out the redistribution since the maali patels and patwaris were 'sources of authenticity for identifying the potential beneficiaries of programmes or certifying the eligibility of small or marginal farmers to get subsidised loans on mortgages...etc.' (Eashvaraiah 1985). This was used as a source of bribes which consisted of percentages of subsidies or commissions for these village officials.

Similarly, the police patel also found ways of making money:

In all the villages, which are situated in the midst of forests or in the vicinity of forests villagers habitually indulge in illegal cutting of wood and do petty business. Whenever the forest officials catch them red-handed the Police Patel of the village has to deal with the case. It has become habitual for both the forest and village officials that they deal with all such cases in a manner which neither benefits the government (by filing a case) nor does it help in curbing the social evil. (Eashvaraiah 1985)

In Hyderabad, the Telugu Desam Party ousted the stronghold of these part-time village officers in 1963, calling it an age-old system of casteism and corruption. Mysore state (changed to Karnataka in 1973) followed suit and the Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act was passed in 1964.

Transition to village defence parties

Under the State Reorganisation Act, 1956, villages and districts in Karnataka were redistributed on a linguistic basis. Bidar district fell under Mysore State (later renamed Karnataka in 1973) and was positioned at the cusp of the Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka border. This resulted in a unique cultural composition, with diverse communities and cultures that had settled generations earlier, continuing to coexist with one another. This shift also affected grassroots administrations in these communities and villages, as the role of the village patel slowly began to dissolve.

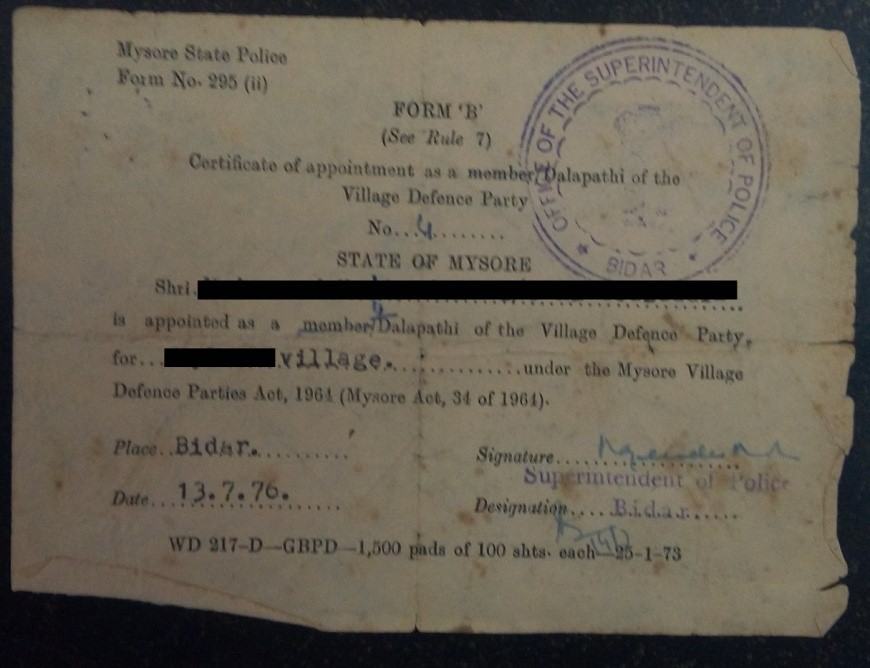

The Patel/Patwari system was formally abolished in 1963, and in 1964, each village was appointed a dalapathi through the Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act, 1964. The Gram Rakshak Dal or Village Defence Party (VDP) was the earliest known community policing program established in villages in the States of Maharashtra and Gujarat. The Bombay Police Act, 1961, empowered the Superintendent of Police to select VDP members as they deemed fit to support the police officers in patrolling, resolving minor disputes among neighbours, and informing the police of bootlegging, gambling, drug peddling and other crimes. A separate act called The Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act (KVDP Act), was passed in Karnataka in 1964. It became fully operational in 1975 and also empowered the district superintendent of police to constitute dalapathis or village heads who were supported by the VDP members (Nalla and Newman 2013).

The KVDP Act, can be looked at as a community policing model, with the VDP members appointed as providers of a community service and the dalapathi as their single representative. As per the 1964 Act, 'For every Village Defence Party, the Superintendent shall appoint one of its members as Dalapathi whose powers and duties shall be such as may be prescribed.' These prescriptions are also mentioned in the dalapathi rule book issued by the Karnataka State Police, in Kannada. This book contained the rights, duties and responsibilities of a dalapathi and was used to disseminate the act to them. The dalapathi rule book was published in 1965 and still acts as a physical artefact representing the purpose and function of the dalapathi.

Village defence parties and community service

In the context of policing, it is also important to clarify the definitions of community and community policing. ‘Community’ here refers to villages, people of diverse cultural backgrounds sharing common perspectives and needs on safety and security within the same geographical location. Drawing from Tapan Chakraborty’s (2003:251–62) explanation of the nature of community policing, 'the first key characteristic of Community Policing should be geographically, and demographically, a foot-patrolman to know all and everyone in a span of time and in turn, be himself known.' These characteristics remained true to the description of the dalapathi’s role as inferred from their experiences as well as from the KVDP Act. The dalapathi was also responsible for maintaining a thorough knowledge of the community and its members and for being proactive in maintaining order and preventing crime.[ii] The dalapathi was also assisted by the VDP members, which made it a more inclusive system, contrary to the previous village police system.

Community policing programmes initiated in various urban and rural settings can be understood as attempts to bridge the gap between the police and villages. Community involvement in law and order became important to reconcile the grassroot communities with the formally oppressive institutions of police. Due to its colonial history and seen as a tool of foreign power, people never considered the police as protectors or as a friendly force (Pujar 2015). The increased political awareness of Indians post-Independence also meant that it was in the government's favour to rid the police of its negative connotations and help it build a positive relationship with the community. Independence also brought politics and a people’s government to a neglected rural India. The villager was becoming politically aware and began to see the government as his own, present for his welfare. Whereas, before the nationalist movement, the villager perceived the government as 'a tax collector, a system of courts and an oppressive police force' (Srinivasan 1956).

The role of the police patel was strongly felt in the rural parts of Bidar district before their dissolution, but they were quickly replaced by the dalapathi post-Independence. The shift from a deep-rooted hereditary and hierarchy-based village administration came to its formal end, and the introduction of a community-centered programme of village policing resulted in a shift in the social dynamics of the village. The Devraj Urs government also initiated social reformation through various development programmes, aimed towards the upliftment of the backward classes. The implementation of the KVDP Act, 1964, and the appointment of the dalapathi timed well with the ongoing social shifts catalysed by the politics in the state.[iii]

The Dalapathi system in Bidar

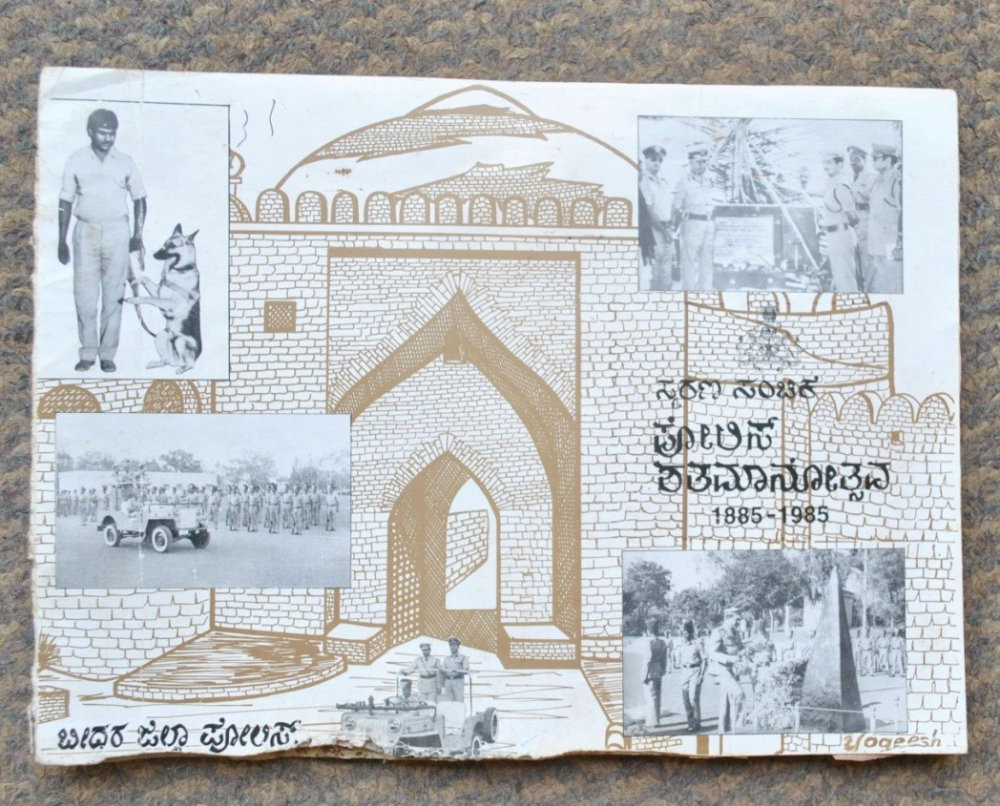

Due to the minimal documentation available about the Dalapathi system itself, artefacts, documents and photographs become useful tools of memory, and also provide insight into the workings of the system. A centenary volume published by the Bidar District Police in 1985 provides a glimpse into the transitions experienced by the Bidar Police, post-Independence and till 1985. The first article in the volume titled ‘Some Transitional Aspects of Policing in Bidar District’, by M.K. Srivastav, the SP at the time, gives an introduction to the feudal system of administration and policing in the region, its transition to the Hyderabad state and the eventual organisational set-up of the Bidar Police. He makes a short mention of the administrative systems under the Nizam’s rule, i.e., Jagir Police, Paiyga Police and Sarf-e-Khas police, which were abolished under the Hyderabad Jagir abolition Act, 1950, and taken over by the Diwani police.[iv] He writes:

The present police administration is one of the transition from diwani and jagir systems of Nizam’s regime. Bidar district was unfortunately a neglected District. Literacy was hardly 4-5 per cent. Except for a road from Hyderabad to Osmanbad via Bidar and Udgir, there was no other means of communication. The backwardness of the area, inefficient management of the paiyaga and jagir administration had resulted in a situation where the anti-social elements had the upper hand. There are legends about dacoits Narsayya Mang, Chanveer, Akbar Khan and Razak who used to loot the rich...during the last days of the Nizam, the communal harmony was at the lowest ebb, law and order situation had worsened. (Srivastav 1985)

The curation of articles within the centenary volume also signifies their new position on community involvement as well as the image they would like to build within these communities. 'The highlights of change of Police set up after reorganisation is that the role of Police force has changed...In the Nizam’s dominion, a Police Constable was representative of king, his word was law and unlimited powers were vested in him. In a democratic set up a complete and different image had to be built up. A Policeman has now to perform and conduct himself as a Public servant' (Srivastav 1985).

Fig. 1: 100-year centenary volume published by the Bidar District Police Department in 1985 under the supervision of M.K Srivastav, SP of the District and Chairman of District Committee at the time. Published for the purpose of ‘Shatha Manotsava’ in 1985 to celebrate and commemorate the completion of 100 years of the Mysore State Police, which later became the Karnataka State Police. Every District Police department in the state published their own centenary volume for this event.

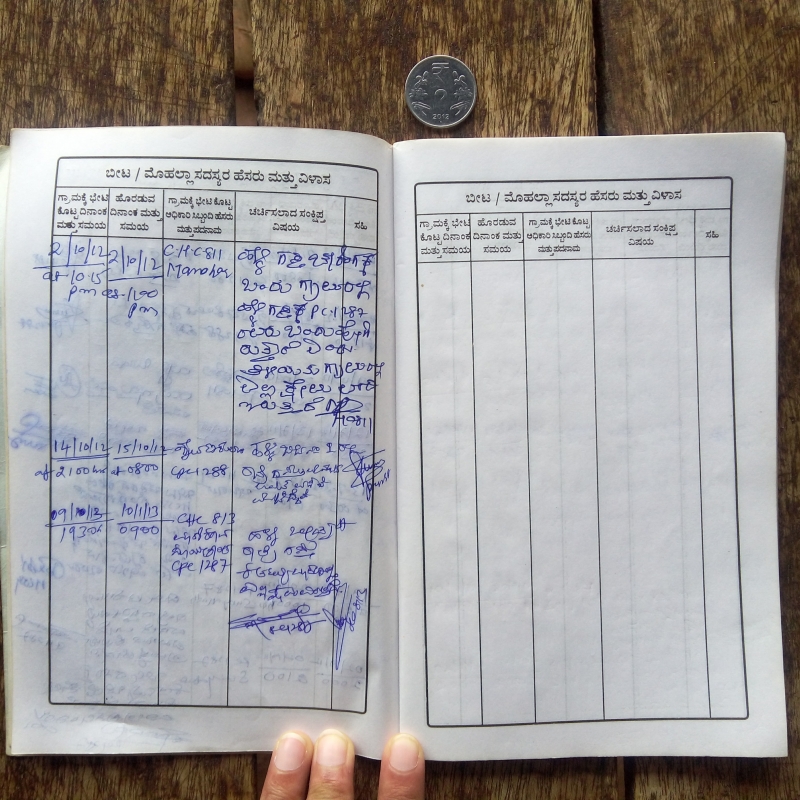

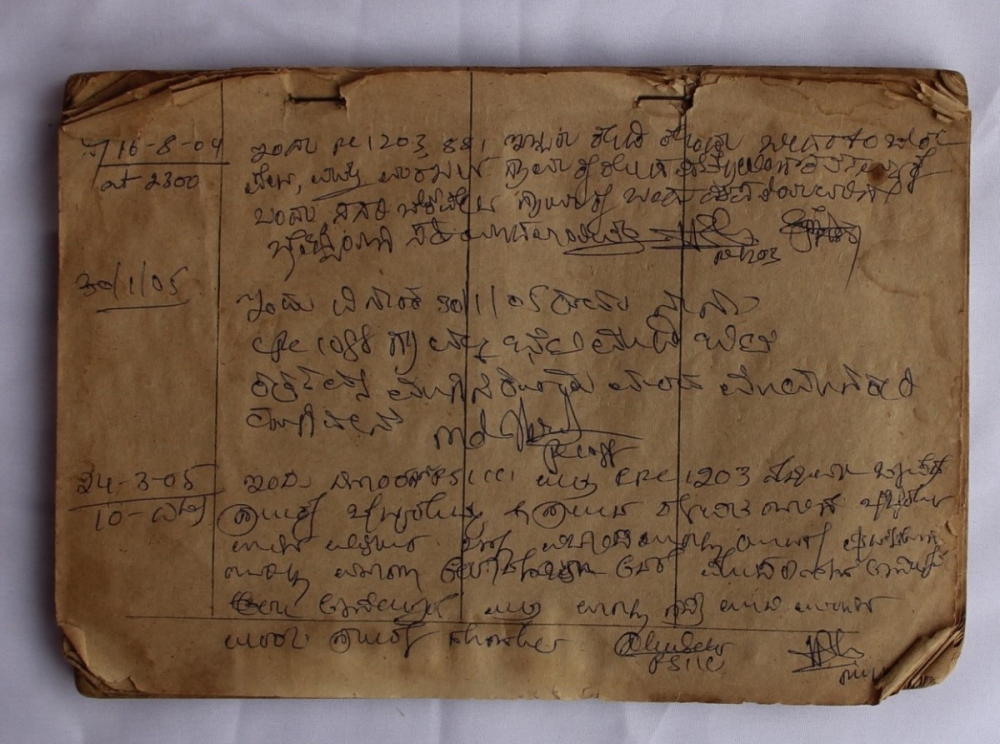

Some of the documents owned and found in possession of dalapathis was the Beat Report or Point Book. The dalapathi maintained a Beat Report that was signed by the appointed Beat Constable of his village, once in every 8–10 days. If any fights, disputes, thefts or suspicious activity was noticed by the dalapathi, it was mentioned in the Beat Report and the Beat Constable would sign across the statement acknowledging that he had looked into the matter during his village beat. In case the village atmosphere was peaceful, the same would be recorded and signed in the Beat Report.

Fig. 2: Narsappa Dalapathi’s Point Book or Beat Report maintained since his appointment in 1976. ‘I cannot read and write. The entries are not written by me, police write it. They come on the beat and write down the date and time of the visit,’ says Narsappa Dalapathi.

Fig. 3: Appointment certificate given to dalapathis in 1976.

Sri Narsa Gonda, son of Bhima Gonda of Chikpet, was appointed dalapathi in 1975 and it is through his personal accounts that one can imagine and understand the implications of the Karnataka Village Defence Parties Act in rural Bidar. Although the dalapathi is described as a police informant by police officials, individuals such as Narsappa Dalapathi helped break the notion of it being a single-function role, as dictated by government-laid rules and procedures. The title was often influenced by the individual holding it, his values and experiences shaping the position he represented and the level of his pro-action. Narsappa (pers. comm., 2017) recounts an incident at the beginning of his appointment, i.e. around 1975, when poverty and robberies were rampant in Chikpet, with livestock being stolen frequently:

The thieves used to come during the rains because there was rain and there was no electricity. They used to push the door. If they hit the door, I would come and quietly sit in front of the door with a stick and battery torch. If they pushed again, I would shout out and they would run away. Sometimes, I would put a steel plate on the door handle. So if the thief pushed the door the plate would fall on the floor and make a loud sound and they would run away. If I heard a loud sound outside, then I would take my torch and go outside.

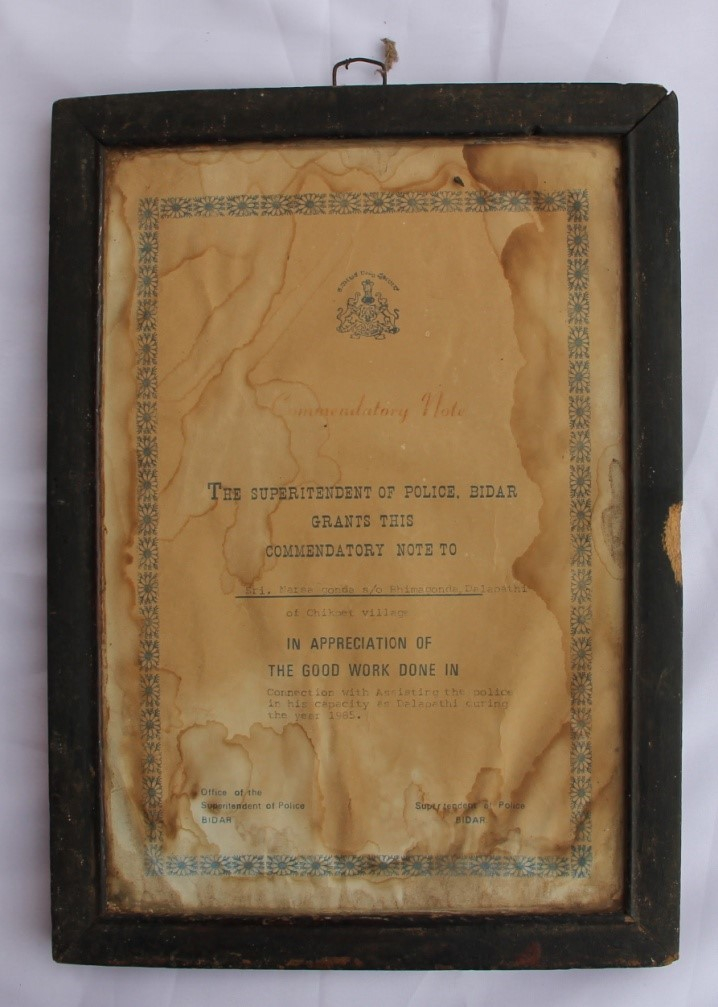

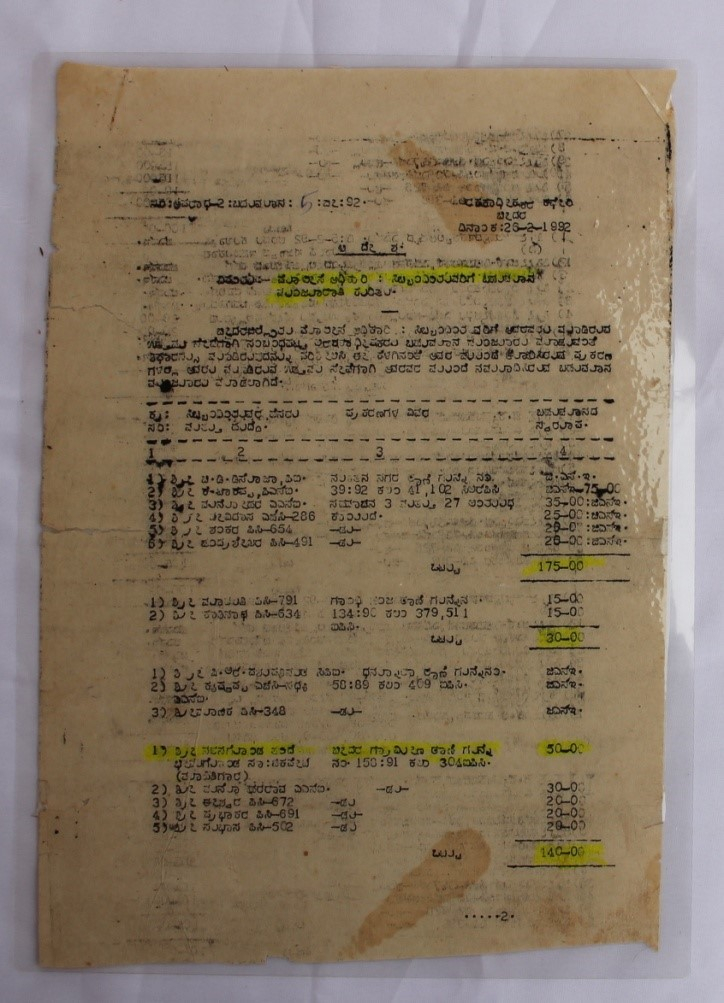

A Dalapathi Union was created in the 1980s for the purpose of petitioning for monetary compensation. Writ petitions were filed by all the Dalapathi Union members in the High Court. Many still await a compensation they feel is rightly due for the costs incurred and the risks they took to keep their respective villages safe and provide necessary intelligence to the police when required. However, there were several rallies organised by the Bidar District Police, where selected dalapathis were commended for their work and given certificates with small cash prizes. The intention of these rallies was to keep their morale high and encourage dalapathis to continue their good service towards the police and their communities.

Fig. 4: Certificate of Commendation awarded to Narsappa Dalapati for his contributions in the year 1985.

Fig. 5: Cash prize awarded to Narsappa Dalapati in 1992 for his services.

Gurusidappa, a retired assistant sub-inspector, in an informal conversation about his service in Bidar, also mentioned how the dynamic environment of the villages, with constant migration between cities and rural areas, affected people’s attitudes towards the appointed dalapathis.[v] With blurring boundaries between urban and rural India, the perceived role of the dalapathi slowly became irrelevant, as people preferred to go directly to the police instead of through the dalapathi. With the introduction of the Panchayat Act in 1983, villages were said to have become highly politicised. Soon, the Dalapathi System, which began as a community policing initiative, a voluntary service, developed political overtones, with political parties pushing for their own supporters to be selected as dalapathis in their villages. ‘Villages were already divided on the basis of caste, class, religion and now also political affiliations,’ said retired DGP and ex- SP, M.K. Srivastav. This eventually led to the dissolution of the Village Defence Party system, and the act was formally repealed in 2004.

Conclusion

Community policing in the Indian context is unique because of the presence of resilient social and economic hierarchies in Indian communities. The police patels from the Jagir administration to the Dalapathi system of contemporary India, both titles created social value in the form of community and institutional relations between villagers, the police and the VDP. The transitioning out of a hereditary and hierarchical system at the village administration level changed the social dynamics in villages as power structures were shuffled. Social mobility is also dependent on the individual’s own capacities and tendencies. This, coupled with the narrative of their own community histories, brought open interpretation to a formal system. Due to the informal nature of its interpretation, not much has been documented about the work of the VDP members. Therefore, memory supported by personal and public artefacts provide a subjective view of the past. Variables of morality and ethics, cultural and social background of the individual also provide a more nuanced understanding of the Dalapathi system and the KVDP Act, 1964. The introduction of the Dalapathi system had its own social implications, and the personal stories and experiences of the people involved, provide valuable insight into the system itself.

Notes

[i] The Bidar Police History Museum and Heritage Centre project proposes to connect cities residents with their inherited legacies and sensitise people to police history and procedures in Bidar.

[ii] Information gathered from interviews with dalapathis in Bidar District.

[iii] Refer to the article titled ‘The Dalapathi System, Individual and Community’.

[iv] Derived from the Bidar Police Department Centenary 1885–1985.

[v] Refer to the article titled ‘Dalapathi system, the Individual and Community’ for Gurusidappa’s extended quote.

References

Arnold, David. 1976. ‘The Police and Colonial Control in South India.’ Social Scientist 4 (12).

Bayley, David. 1971. ‘The Police in India.’ Economic and Political Weekly 6 (45).

Chakraborty, Tapan. 2003. ‘Prospect of community policing: An Indian approach.’ The Indian Journal of Political Science 64 (3/4):251–62

Eashvaraiah, P. 1985. ‘Abolition of Village Officers: Revolutionary on the Surface.’ Economic and Political Weekly 20 (10).

Nalla, Mahesh K., and Graeme Newman. 2013. Community Policing in indigenous communities. CRC Press.

Pujar, Mangoli. 2015. ‘The Emergence of Community Policing in Karnataka: An Analysis.’ Forensic Research Journal 6 (4).

Sharma, Anupam. 2004. ‘Police in ancient India.’ The Indian Journal of Political Science 65 (1).

Srinivasan, N. 1956. ‘Village Government in India.’ The Far Eastern Quarterly 15 (2).

Srivastav, M.K. 1985. ‘Some Transitional aspects of policing in Bidar’. In Police Centenary 1885–1895: A commemoration Issue. The Bidar District Police.

Further readings

Nalla, Mahesh and Manish Madan. ‘Determinants of Citizens’ Perceptions of Police–Community Cooperation in India: Implications for Community Policing.’ Asian Criminology 7, no.4 (2012): 277–94.

Kahan, D. ’Reciprocity, Collective Action, and Community Policing.’ California Law Review 90, no. 5 (Oct. 2002):1513–39.