The different phases of Ajanta paintings

Dieter Schlingloff

The Paintings of the Second Century B.C.

2. The Buddha in Previous Existences

3. The Superhuman Events in the Buddha’s Life

The Paintings of the Fifth Century A.D. 6

2. The Buddha in Previous Existences

3. The Birth and Youth of the Bodhisatva

4. Episodes from the Life of the Buddha

Introduction

The wall paintings in the Buddhist cave monasteries of Ajanta are of equal significance for the history of ancient Indian culture as the frescos of Pompeii for Greco-Roman antiquity: they are almost the sole preserved records of an art which belonged to the greatest achievements of its time. The Ajanta paintings are not just a milestone in the history of the development of world art, they also convey unique insights into the life of the ancient Indians and their culture. The painted Buddhist legends proclaim ethics, in which help for beings in distress is valued higher than one’s own personal welfare, and is often even worth more than one’s own life.

If the Ajanta paintings until now have not received the attention that they deserve, then this is very much due to their poor state of preservation and the resulting unsatisfactory publications.

About two thousand years have passed since the creation of the oldest wall paintings and about fifteen hundred years of the more recent ones, and the ravages of time have left their scars on the pictures. Many paintings have fallen off the walls with the layer of plaster on which they were painted and have thus been irretrievably lost; parts that are preserved are often faded or worn off, darkened by soot from lamps or washed out by bats’ urine, badly scratched by visitors’ graffiti or discoloured by amateur attempts at restoration. This is the reason why the books representing Ajanta paintings almost always reproduce the same excerpts from the pictures, which purely by chance happened to be better preserved. It is as impossible to do justice to the character and quality of the paintings with such reproductions of details, as it would be if one were to extract one single small figure from a huge Baroque painting on canvas and reproduce it as a full-page picture plate. In Ajanta too, it is not small, isolated genre pictures which form the contents of the paintings’ depictions, but extensive narrative representations which are composed of numerous individual scenes and interwoven. A comprehension of the contents and appreciation of their artistic merit is only possible if the extensive compositions can be viewed in their entirety. The eye of the beholder first takes in the scenery of the town and country landscapes in their harmonious alternation, and then proceeds, step by step, to recognize the narrative actions imbedded in these landscapes – an aesthetic and intellectual sensation which can never be conveyed by photographs of details.

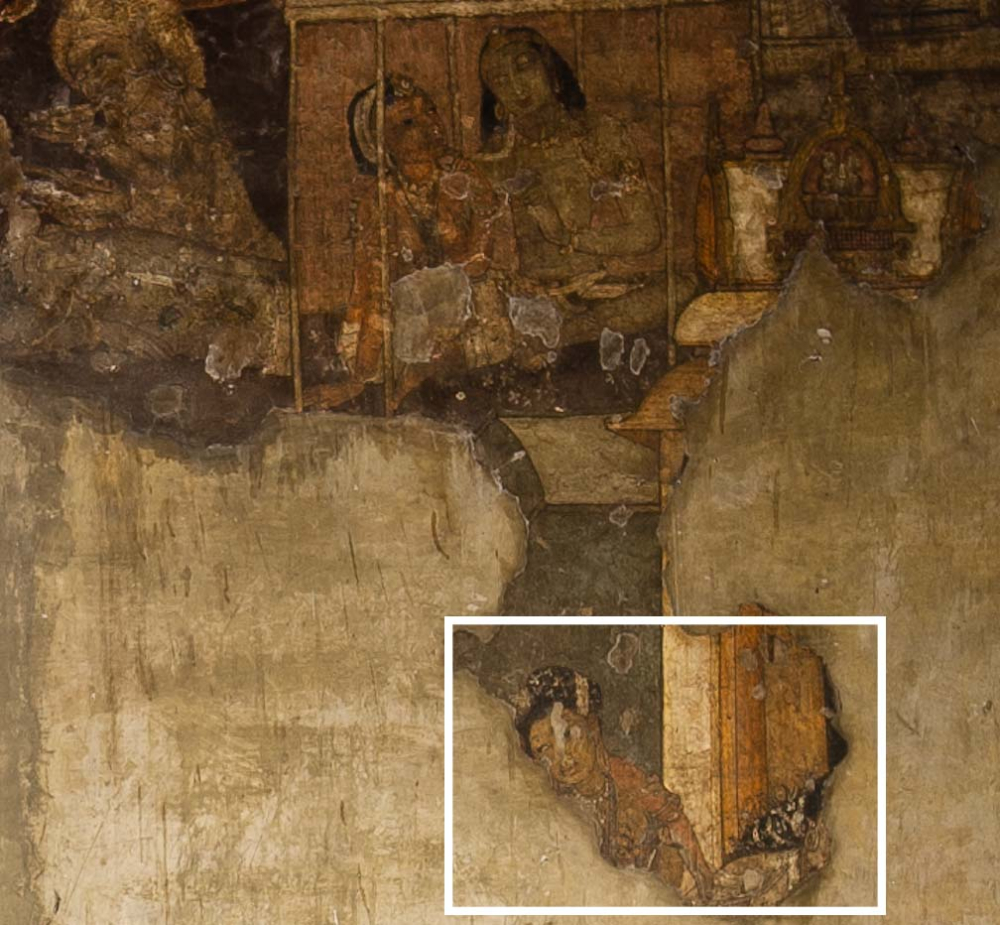

Fig.1. "The lover's arm", Ajanta cave 17

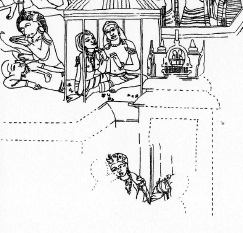

The emphasis on details which are mostly of little significance for the contents and often of inferior quality not only impedes an adequate artistic assessment, it can sometimes lead to grotesque misinterpretations. Thus, for example, in one frequently published painting fragment a woman is depicted, behind whose left arm a man’s arm can be discerned. The usual interpretation of this picture as a loving caress appears to be impossible for the mere reason that this arm reaches so far down, that the whole weight of the man’s body is on the woman’s shoulders. A study of the picture in its context reveals unambiguously that this arm does not belong to a lover, but to a shipwrecked man, close to death from exhaustion, who is being dragged by the woman from the coast of the island through the city gate to her house. In the houses inside the city the shipwrecked merchants really do sit together in cosy companionship with the charming island women, who are in reality man-eating witches (Figures 1-3: “The lover’s arm” (No. 58 (2))[1].

Fig.2. "The lover's arm", Ajanta cave 17

Fig.3. "The lover's arm", Ajanta cave 17

The narrative materials on which the paintings are based belong, in a slightly Buddhist variation, to many different literary genres. We find hunting adventures, (No. 6, No. 7, No. 16, No. 19, No. 20, No. 23, No. 31, No. 53, No. 57) as well as travel adventures (No. 40, No. 41, No. 58) and even romances (No. 5, No. 40), also stories giving examples for both clever and ethical behaviour in general (No.1, No.3, No.4, No.21), but especially in the affairs of state (No. 2, No. 35, No. 37, No. 38, No. 42, No. 43, No. 57, No. 58, No. 61), and last but not the least comical tales about stupid ascetics and Brahmins (No. 32, No. 33, No. 34, No. 38). Just as in the art of poetry, in the wall paintings too these narrative materials were artistically arranged and, just like in the art of poetry, the art of painting created certain clichés on which the individual designs of each artist are based. The pictorial design of the paintings needs just a few clichés which explain the places of action and the events taking place in them straight away to anyone familiar with this pictorial language; it is only the uninitiated person who requires a written or verbal interpretation, just as someone unfamiliar with the language of poetry requires a commentary.

There is, however, a fundamental difference between the works of poetry that have been handed down and the paintings that have been preserved: whereas of the countless works of poetry once composed, those that are preserved are the ones which were considered to be most deserving of preservation by repeated copying, it is pure chance that of the uncounted wall paintings which once decorated the walls of many buildings, only those on the walls in Ajanta and some other few monastery caves are preserved; with the lost cities, the painted walls of the palaces and residences were also irretrievably lost. The highlights of the art of painting were surely to be found in the royal palaces, and the paintings in the cave monasteries are only a pale reflection of their beauty which allows us to guess at the artistic quality of the masterpieces. The dark cave monasteries are most unsuitable for the presentation of the pictures, because the paintings are only clearly discernible in the evening, when sunlight penetrates into the caves for a short time. The fact that such caves were painted at all is only due to the circumstance that sponsors who were favourably disposed to Buddhism wished to give the monks the opportunity to impart their teachings to the numerous monastery visitors through pictures as well as through words.

However, this also means that the themes of the preserved paintings were rearranged in the Buddhist spirit, and, in some few cases, were invented by the monks themselves. Thus the wall paintings are pictorial sermons which were supposed to impart two fundamental teachings of Buddhism: firstly, they are supposed to show that the Buddha, master and example for monks and lay-people, is at the same time a being who is exalted above all people and whose periodical appearance reroutes the course of world affairs; secondly, they are supposed to render visible that this being, before he became the Buddha, sacrificed himself for others in countless existences as the Bodhisatva, thus pointing out to an unkind, cold and egotistical world the one way in which the existence as a human being can be brought to perfection.

The Paintings of the Second Century B.C.

1. General observations

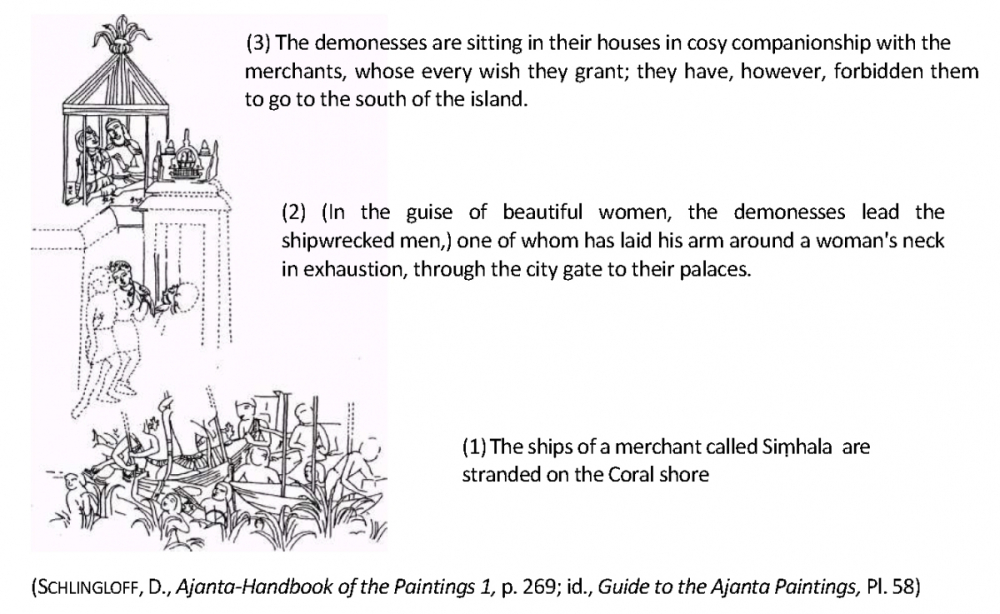

The halls of worship have preserved the oldest Indian narrative wall paintings in picture strips, which escaped being repainted in Ajanta’s later art period. In spite of their poor state of preservation, these remains of pictures, with their perfected lines, coloration and scene design, reveal a developed state of pictorial art, the beginnings of which are shrouded in darkness. Members of the ruling class and the prosperous middle class, who were well disposed to Buddhism, saw to it that the monastery complexes built on their command were decorated with paintings, whose contents the monks could determine, but whose design was certainly in keeping with contemporary secular painting. Like the royal palaces and town houses, the free standing Buddhist monastery complexes are no longer preserved. Old Indian painting has been much attested to in literature, but we owe the possibility of studying it from actual examples to the fact that the cave monasteries, designed analogous to the free standing buildings, were also decorated with paintings, although the darkness of the caves was a rather unfavourable precondition for the decoration with paintings. The Ajanta caves are only lit by sunlight for a short time in the evening; apart from this, however, the walls must be illuminated in order to render the pictures visible. It is only in the artificial light of oil lamps or candles that the later paintings also display their characteristic plastic vividness and brightness, whereas they appear disappointingly cold in daylight, neon lighting or flashlight. The lighting by open lamps for centuries may be responsible for the fact that the preserved remains of the oldest paintings are so dark that not just the coloration, but even the outlines are hardly discernible; the paintings in later caves, which apparently were abandoned not very long after their completion, show no such darkening caused by soot. According to Lüders' ascertainment of the date of an inscription written on one of the paintings (Figure 4: The oldest painted inscription (No. 8(2); p.50), the old paintings in Cave X date from the middle of the second century B.C.; Cave IX is considered for architectonic reasons to be somewhat older than Cave X.

Fig.4. The oldest painted inscription, Cave 10

2. The Buddha in Previous Existences

The Buddha of our epoch, like all living beings, was reincarnated countless times before he attained enlightenment, founded his community and entered into Nirvāṇa. As an Enlightened One the Buddha was omniscient and was able to remember all his previous existences as the Bodhisatva. Therefore he could draw upon this knowledge for his sermons and relate events which had occurred in earlier times when he had been reincarnated as an animal, a human or a deity.

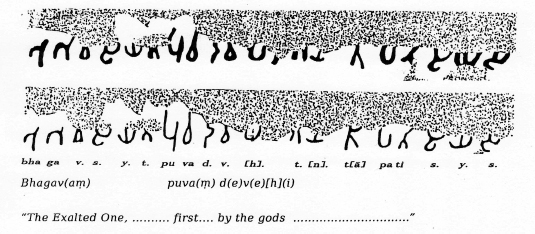

The Buddhist monks who thought up the Buddha’s life and sermons did not have to invent these kind of stories of previous existences themselves. They were able to select suitable topics from the extensive wealth of tales handed down orally from time immemorial, and declare them to be experiences of the Bodhisatva. In this way they created a literary genre called ‘Reincarnations’ (Jātaka), which, as an old list of texts shows, belongs to the oldest stock of Buddhist literature. Over five hundred verse narratives assembled in the Jātaka collection tell of events in the world of animals and humans. They reflect a view of life which is simple but realistic for the ideas of the time, and in which mythological speculations play only a minor role in contrast to the epic poems. The gods in the heavenly spheres, which are arranged one above the other, have hardly any contact with the world of the humans and animals on the surface of the earth. The only ones who occasionally show an interest in earthly affairs are God Indra, usually in his own interest, and, more rarely, God Brahma, ruling in an even higher heavenly sphere. In contrast, certain beings, half god and half man, such as the geniuses (yakṣas) and demons (rākṣasas) and other beings, half god and half animal, such as the birds of prey deities (garuḍas) and, above all, the cobra deities (nāgas) appear relatively frequently (Figure 5: Nāga and Garuḍa (No.1(3)). These beings live on the earth, not in the celestial worlds, but they have the godlike ability to change their true form as they wish. They can also communicate verbally with people and animals, just as verbal communication between people and animals is unreflectedly assumed to be possible.

Fig.5. Nāga and Garuḍa, Ajanta Cave 9

Although such ideas probably already belonged to the stories in their pre-Buddhist form, the Buddhists placed new emphases by identifying the protagonist in each case whenever possible with the Bodhisatva and, in conjunction with this, they elaborated those situations in which the Bodhisatva could put one of the cardinal virtues of Buddhism – generosity, morality, renunciation, steadfastness, goodness or composure – to the test.

In both old caves, the Jātakas are painted as picture strips with narrative scenes. As far as it is discernible, in Cave IX portrayals of short stories in only one or a few successive scenes seem to have been placed beside each other. The question whether this arrangement is purely coincidental or based on an overall concept, must remain open. However, it is conspicuous that celestial beings are involved in all narrative stories preserved in Cave IX: In the Paṇḍara tale (No. 1) a Nāga and a Garuḍa, the implacable enemies are coming together, – in the story of Mahāgovinda (No. 2), god Brahma comes flying down to Mahāgovinda from his hovering heavenly palace, – in the story of the self-sacrifice of the hare (No. 3: Śaśa), a deity comes flying to the scene of the Bodhisatva’s self-sacrifice, – in the Kuṇāla story (No. 4), the divine sage Nārada and his followers are standing around Kuṇālas stone seat while Kuṇāla, the king of glossy cuckoos is preaching, – and in the story of Udaya (No. 5), Udaya, reborn as a Yakṣa, is flying to his former wife in her palace. Perhaps the aim was to make the visitors of this cave aware of the influence of the deities on earthly events by the arrangement of just such stories.

In Cave X, as in the reliefs on the architraves in Sanchi, large narrative complexes were arranged in a large number of individual scenes. The arrangement of the individual scenes does not follow the narrative action; instead, they are allocated to the places where the actions take place, irrespective of their chronological sequence. In harmony with the function of this cave as a worship room for the solemn transformation of the Stupa, these paintings show the beholder following the path of the procession, first the Buddha’s life until the distribution of his relics (No. 8), then two famous episodes of his life-time (No. 9; No. 10), and then two of the best known legends from his previous incarnations, first as a human, the story of Śyāma (No. 6), the pious son of his blind old parents, deadly wounded by the arrow of a hunting king, then as an animal, Ṣaḍdanta (No. 7), the king of a herd of elephants, brought to death by his former wife reincarnated as a human princess.

3. The Superhuman Events in the Buddha’s Life

At the time when the oldest Buddhist paintings were made, there was still no Buddha biography in the sense of a continuous account of the life of the legendary founder of the order. Occasionally sermons and rules of the order were elaborated with biographical information, in order to give them a location in real life; the main motive for the conception of a Buddha’s life was not, however, the intention of giving the didactic speeches an attractive local colour, but one of backing up the dogma that the appearance of a Buddha as the climax and turning point of world affairs was a miraculous event, unlike any other earthly life. The driving forces of the Buddha biography were the ‘Miraculous Iron Laws’ (adbhuta-dharma) of the birth of a Buddha, which belong to the oldest stock of Buddhist literature. Just as the oldest literature wishes to express but the one thing with regard to the life of the Buddha, namely, that this life transcends all human experience, the oldest art always shows the Buddha as an abstract symbol, and never as a person of flesh and blood. Both the literary accounts and the artistic portrayals of the greatest occasions in the life of a Buddha were enriched with details from the human sphere of life. Thus the accounts of these miraculous apparitions became biographical episodes, the oldest ones represented in the reliefs of Bharhut, Sanchi, (old) Amaravati and, last not least, in the paintings on the left wall in Cave X of Ajanta. Here, the main events of the Buddha’s life are depicted in the following scenes:

(1) On the right edge of the ‘Heaven of the Blessed’ are standing a number of deities and a female whisk-bearer, who are looking to the left, i.e., the centre of the painting (where a symbol alludes to the Bodhisatva’s presence, who had chosen this heaven as his temporary abode and, who now decides to descend to earth for his final rebirth).

(2) The grove of the birth, bordering a building on the left and a ceremonial gate (toraṇa) on the right, is marked, in the right half of the painting, by a forest complete with an aśoka tree, a pāṭali, a kadalī and another pāṭalī tree. In the centre of the painting stands the mother of the Bodhisatva who, during child-birth, is clinging with both hands to the branches of a blooming śāla tree and slightly leaning her head to the left, where a woman stands with a whisk of peacock feathers; a drum above her indicates the celestial music accompanying the miraculous event. In the left half of the painting five deities are standing in a lower, three more in an upper tier; the former, in the lower tier, are pointing their index fingers at the event, the latter, in the upper tier, are hurling their shawls up in the air; the one in the middle, moreover, touches his lip with his index finger, to lend expression to his amazement at the miraculous event.

(3) The seven steps of the new-born Bodhisatva are accompanied by a deity with a parasol on the left and two deities on the right, the one in front with a whisk. Here too, a drum hovering above the symbol to indicate the Bodhisatva points at the celestial music during this event.

(4) The ‘First Meditation’ is symbolised by a rose-apple tree around which the king’s warriors have assembled: on the right, armoured bearers of swords with a horse and others with halberds behind them; and bearers of swords and spears on the left. On the extreme left, behind a tree, the king, astride an elephant, is arriving with his retinue to fetch the Bodhisatva.

(5) The Bodhisatva’s presence in the period he reaches enlightenment and becomes the Buddha is symbolised by a pipal (fig-) tree and, at its foot, a stone seat on which stands a nandyāvarta as an auspicious symbol, flanked by two parasols. Beside the tree, on the right, celestial nymphs perform dances to celebrate the enlightenment, the dancers are accompanied by female musicians on flutes and zithers and with rhythmic hand-clapping. To the left of the tree, together with his daughters, stands Māra, ruler of the world of sensuality, pointing at the tree of the enlightenment and, thereby, urging them to try to prevent the enlightenment by their seductive tricks. Frightened at the imminent enlightenment, Māra has placed his left arm on the shoulder of one of his daughters, holding in his right hand the little stick with which he will later scratch the earth in despair over his total failure.

(6) The Buddha’s First Sermon in the Deer Park near Benares, by which he set in motion the Wheel of the Doctrine, is symbolised in the centre by a parasoled wheel flanked with four flying genii. The presence of numerous deities, standing on either side of the wheel in reverence of the preaching Buddha, point at the event’s cosmic importance.

(7) The death of the Buddha in a park bounded on the right by a ceremonial gate is symbolised (by a reliquary) (?) on a parasoled throne, which is flanked by the two śāla trees, blossoming out of season. Beside the śāla tree on the left are standing the Mallas of Kuśinagara, armed and equipped as members of the military nobility, who have come to receive the urns containing the relics allotted by the brahmin.

(8) To claim the Buddha’s relics, the seven kings of the surrounding countries have come to Kuśinagara on their royal elephants and are pleading with the armed Mallas, who are in position behind the city walls. After an amicable settlement, they have turned their elephants around and are carrying the relics away to their princely states on the heads of the elephants.

The Paintings of the Fifth Century A.D.

1. General remarks

After the construction work in Ajanta had ceased for more than half a millennium, in the second half of the fifth century A.D. further halls of worship and dwelling caves were dug into the rocks around the core of the two halls of worship IX and X, so that in its present state the whole complex consists of four halls of worship and twenty-six dwelling caves. Now however, they did not just paint the new halls of worship or paint over the paintings of the old halls – all bare surfaces of the dwelling caves with the exception of the monks’ cells were covered with a layer of plaster and painted step by step. As an unfinished cave shows, sometimes the painting began before the excavation work was completed. The presence of various different styles of painting indicates that the artists were from different regions. The painters were contracted by employers, who, as inscriptions indicate, were often monks. The fact that the dwelling caves got painted as well as the halls of worship is due to the ritualistic function which the dwelling caves now acquired by virtue of their structure. One of the monks’ cells, the most prominent one in the centre, had a portico added on to it and a statue of the Buddha was placed inside; in this way the Buddha sojourns as a monk among the monks and, simultaneously, elevated above all heavenly and earthly beings, as a majestic proclaimer of the way to salvation, in the midst of his monastic community. It was not just the devotional statue, the whole decoration scheme of the cave paintings was meant to give expression to the Buddha's majesty. Bodhisatvas as celestial kings in mythical mountain landscapes flank the doorways of the veranda, the ante-cell and the cell, in other words, of the way along which the believer can walk in a straight line in order to bow at the feet of the Buddha statue. The figures of these celestial kings, who serve the Buddha, king of all kings, as door guards, tower above the other figures, which are painted on the walls to the same scale. In the midst of this stylised mountain world with mysterious magical beings, these Bodhisatvas in their majestic appearances belong to the greatest achievements of the Ajanta paintings.

The narrative paintings on the cave walls reveal a programme of pictures, consisting of a harmonious alternation of episodes from the Buddha’s life (veranda and main hall) with stories from his previous existences (portico and main hall) and devotional pictures of the central events of the Buddha’s life (rear wall of the main hall and ante-cell). However, with the possible exception of Cave XVI, this programme of pictures was not always followed through consistently. These inconsistencies can probably be put down to the fact that the painting was not carried out in one go; when painting work which had been temporarily abandoned was later taken up again, other standards of decoration, possibly corresponding to the ideas of the contractor of the time, dominated. Apart from the harmonious alternation of stories from the previous lives with legends from the Buddha’s life, which was originally intended, the paintings of the individual caves show no signs of a programme of pictures which could be attributed to a certain work of literature or a certain ideological concept. The literary topics which were represented as pictures, originate for the most part from the large Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādin School (MSV), as well as from the verses of the Ārya Śūra (ĀJM) and Aśvaghoṣa (Saund.). All the works of literature connected with the paintings belong to the “Hīnayāna” and accordingly, themes that are particularly “Mahāyānistic”, with the possible exception of the Avalokiteśvara devotional pictures, were not portrayed. The term “Mahāyāna caves” for the later caves, which originates from the time when the literary background to the paintings was still unknown, can therefore only be used as a label; it would be a mistake to form conclusions about the ideology behind the paintings on the basis of this term.

As in the pictorial art of the oldest period, here too the literary contents were visualized in such a way that the narrative action was divided into individual episodes, each of which was staged individually; the only difference being that here the pictures were not lined up beside each other, but were distributed around the available wall space in accordance with the spatial principle of order. Thus a scenery filled with the eventful life of royal palaces, cities, parks, wildernesses, lakes and seas, was created, mostly without regard to the chronological order, which presents the visitor with an impressive picture of the scenes of action, where the individual episodes take place, but which at the same time requires him to find these episodes in the scenes of action and to place them in time.

2. The Buddha in Previous Existences

Whereas the paintings of the Buddha in previous existences in the old Caves IX and X are based solely on the verses of the Jātaka Collection (J.v.), the Sanskrit versions of the “northern” schools of Buddhism were definitive for the later paintings in Caves I, II, XVI, and XVII. In these schools the ancient scripts of the teachings and discipline of the order were translated into Sanskrit, and in addition to this, of the stories that had been passed down, some were transformed into works of poetry, while others were integrated into the scripts of the teachings, especially into the scripts on the discipline of the order, in order to illustrate the theoretical discussion with practical examples. In doing so, some of the old verses were given a free rendering in Sanskrit, most of them, however, were substituted and added to by a prose text, which did not recount the plot in excerpts or merely in passing, but in extenso. In addition to this, other narrative materials, which are not to be found in the old Jātaka collection, were revised in the sense of the monastic ideology and incorporated into the Buddhist writings, in the same way as had been done before with the narrative materials on which the Jātakas themselves were based. The stories the painters transformed into pictures have many different origins; their original genre is still visible through the Buddhist revision. The topics being secular in origin, the painters could design their pictures in accordance with the clichés they were familiar with from painting palaces and citizens’ houses; at the same time, the Buddhist revision of these stories gave the monks an opportunity of proclaiming the Bodhisatva ideal, which culminates in the goal of equalling the Buddha, who has worked for the salvation of all beings in countless reincarnations, by means of their pictures. Even as an animal the Bodhisatva proved his virtue. He remained loyal to his parents (No. 27) and his friend (No. 13), as king of the animals he protected his herd (No. 11), sometimes sacrificing his own life (No. 19, No. 30). Most of all, however, he sacrificed himself for people (No. 15, No. 16, No. 20, No. 23, No. 24, No. 25, No. 29), who often repaid his act of rescue with ingratitude. In his human incarnations, the Bodhisatva as a Brahmin ascetic did not curse those who did him harm (No. 31, No. 33, No. 34, No. 35) and sacrificed his life to save animals (No. 36). As a minister, he proved his cleverness (No. 38) and loyalty (No. 37); as a king or prince he gave away everything belonging to him (No. 42), rescued people from dangerous situations (No. 56, No. 58) and sacrificed himself to save others (No. 46, No. 48, No. 49, No. 50). The pictures of the wall paintings were even more appropriate than the words of the poems and sermons to inspire both monks and lay-people with this Bodhisatva ideal.

3. The Birth and Youth of the Bodhisatva

Even in the paintings of the 2nd century B.C. the central events in the life of a Buddha, designed as miraculous events, were being enriched with episodes which imbedded these miracles in a quasi-historical context. The Mahāvadānasūtra, which arose from the account of the “Miraculous Iron Laws” (adbhuta-dharma; cf. above), was later extended to a biographical account of the life of the Buddha up to his enlightenment by supplementing it with events with motives originating in the world of epic heroes, the main message of which is that the future Buddha is far superior to all his contemporaries in everything. This biography of his youth constitutes the literary background of our paintings; here, in contrast to most of the other stories from the previous incarnations of the Buddha, the artists were not forced to divide the continuous action into individual episodes, because these episodes had, for the most part, already been pictorially formed as independent units before they were composed to a sequential narrative action in the biographies. Therefore, the artists used the older pictorial depictions of these episodes, especially in the relief art, as examples, in addition to the literary sources. The question whether, and why, the painters accorded priority to the textual source or to the pictorial tradition in their depiction of the scenes, must be examined for each scene individually. The most elaborated of the paintings of the ‘Life of the Buddha’ beginning with his last existence in the Tuṣita heaven and ending with the first event after his enlightenment is depicted on the left wall of Cave XVI. The 31 scenes of this composition, based on the text in the Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādins may be labelled as follows:

(1) The Bodhisatva in the Tuṣita heaven; (2) The Bodhisatva’s entering into his mother’s womb; (3) The interpretation of Māyā’s dream; (4) Māyā’s desire to visit a grove; (5) Māyā’s journey to the Lumbinī grove; (6) Birth of the Bodhisatva; (7) The Bodhisatva’s seven steps; (8) The Bodhisatva’s ablution; (9) Śuddhodana’s reverence to his son; (10) The cleansing of Māyā; (11) Concurrent births; (12) Return to Kapilavastu; (13) Presentation of the Bodhisatva in the temple; (14) The intrusting of a nurse; (15) Summon of the readers of portents; (16) The visit of the sage Asita; (17) The Bodhisatva going to school; (18) The Bodhisatva’s physical education; (19) The archery competition; (20) The Bodhisatva choosing a bride; (21) The four encounters; (22) The meditation under the rose apple tree; (23) Śuddhodana’s brothers; (24) The Great Renunciation; (25) The encounter with Bhārgava; (26) The visit to Rājagṛha; (27) King Bimbisāra’s visit; (28) The meeting with five Ṛṣis; (29) The molestation of the Bodhisatva by village youths; (30) The offering of milk-cream; (31) The meeting with the ascetic Upaga.

4. Episodes from the Life of the Buddha

The Buddha biography contains a number of episodes in which the Buddha is not in the centre, but people who had a fateful encounter with the Buddha: members of his family (No. 68: Śuddhodana, No. 69: Udāyin, No. 70: Rāhula, No. 73: Nanda), kings (No. 75 Udrāyaṇa), Brahmins (No. 67: Kāśyapa, No.72 Sumati, No. 78 Indrabrāhmaṇa), merchants (No. 79 Pūrṇa), women (No. 74: Sumagadha) and even animals (No. 77: Elephant Dhanapāla). The conversion of these people is usually the goal and climax of each episode. The figure of the Buddha is not put into the centre as in a devotional picture; it is integrated into the depictions of the course of events; it is only by means of his size, which surpasses everyone else, that the dominating role of the Buddha is visibly brought to expression.

Captions

Figure 1 “The lover’s arm”, Ajanta Cave 17, Simhala Avadana, #58(2). Photo: R.K. Singh courtesy of ASI

Figure 2 “The lover’s arm”, Ajanta Cave 17, Simhala Avadana. Source: (#58(2), Schlingloff 2013, vol. I, 269)

Figure 3 “The lover’s arm”, Ajanta Cave 17, Simhala Avadana. Source: (#58(2), Schlingloff, 'Memorandum,' unpublished)

Figure 4 The oldest painted inscription, Ajanta Cave 10. Source: (#8(2), Schlingloff 2013, vol. I, 50)

Figure 5 Nāga and Garuḍa, Ajanta Cave 9. Source: (#1(3) Schlingloff 2013, vol. I, 19)

References

Schlingloff, Dieter. 2013. Ajanta: Handbook of the Paintings. III vols. New Delhi: IGNCA and Aryan Books International.

—. 1999. Guide to the Ajanta Paintings: Narrative Wall Paintings. Vol. I. II vols. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd.

[1] These are narrative index numbers whose details can be found in (Schlingloff, Guide to the Ajanta Paintings: Narrative Wall Paintings 1999) and (Schlingloff, Ajanta: Handbook of the Paintings 2013).