A Study of Ajanta Paintings

Prosperity in this World Instead of Nirvāṇa?

Understanding the Arrangement of the Paintings in the Caves of Ajanta and Their Comparative Soteriological Significance in Terms of Relevance or Irrelevance for Enlightenment

Monika Zin

It is a matter of common knowledge to all students of Buddhism that the old cults of yakṣas, nāgas, and other “low-grade” divinities were incorporated into Buddhism’s religious beliefs, scriptures, imagery, and art. How, though, did this process work? Is it possible to isolate “low-grade” representations from the others? And, most importantly, were the yakṣas and the other divinities really understood by believers of the time to be “low-grade”?

Ajanta is the single location where not only the representations, reliefs, and paintings have been preserved on such a great scale but where we are still able to view them in situ, still in their original architectural setting, revealing contrasting associations. In addition, Spink’s differentiation of the elements of decoration into “program” and “intrusions” (e.g. in Spink 2009: 82f) provides us with a means of isolating these “intrusions” and ascertaining the contents of the programmes of the caves’ decorations as they were originally intended. Imagining how the caves would appear without these intrusions leads us to a revelation which can only astonish a visitor to the caves: The Buddhas, visible today throughout the caves, were not in the original decoration – the figures were added at a later date. The yakṣas and the nāgas, however, were present in the original design. What was their function in the Buddhist monument? Were they there to exalt the Buddha, or for the protection of the visitors?

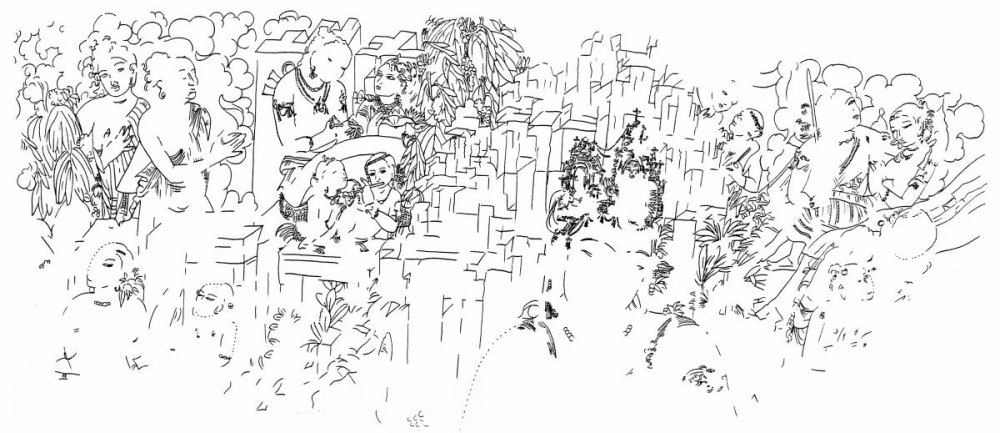

Fig.1

Fig.2

Let us look, for example, at the façade of the Cave XIX (Fig. 1).[1] Here, we see two standing yakṣas with round bellies who dominate the composition (Fig. 2); they are standing on sturdy, slightly-too-short legs in poses that are mirror images of each other, flanking the window opening. They hold money bags and are accompanied by dwarves; one of them is pouring coins from a sack (Fig. 3).

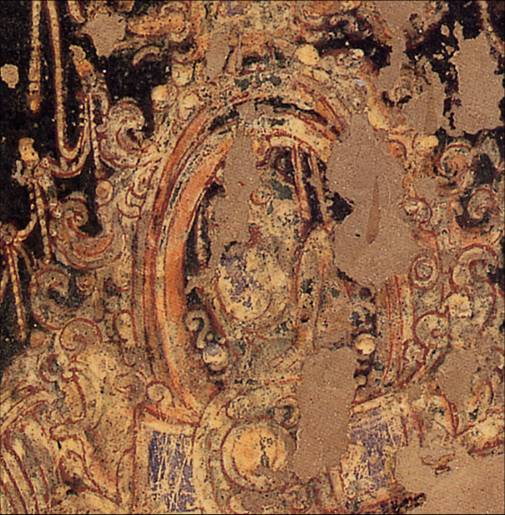

Fig.3

Conch-shells spilling out coins appear in the ornaments of the façade just to the side of this image. All that we see here is of auspicious character, and symbolizes richness and opulence – in fact, it is not a painting that properly prepares the visitor for his or her entrance into the sanctuary of the Buddha, or to concentrate on enlightenment, nirvāṇa, or his or her own Buddhahood. When one looks closely at the turbans of both yakṣas, it is possible to discern something quite astonishing (Figs. 4-5) in the opulent decorations on the turban.

Fig.4

Fig.5

Located on the sides of the turban, hardly visible for the viewer and as if they were of no relevance, Buddhist emblems appear. One yakṣa bears a Buddha and another a stūpa; i.e. symbols which the art historian connects with two important Bodhisatvas, Avalokiteśvara and Maitreya. Are we wrong here in understanding the deities on the façade to be yakṣas? Or we are perhaps wrong in our interpretation of deities having such attributes as Bodhisatvas? We can go still further, and ask if, perhaps, our perception of the distinction between Bodhisatvas that protect and yakṣas that bring luck is merely a manifestation our own need for an unambiguous explanation, a label which was simply not important – or perhaps even non-existent – in early times.

The façade of the Cave XIX is representative. The yakṣas, with their imagery of material wealth and these barely-discernible Buddhist aspects, dominate the representation. On the sides of the entrance door, figures of standing Buddhas appear; these are however not really objects of worship, and are also mirror-inverted, rather flanking the way in the interior of the image. The representations around the Buddhas reveal their narrative character. One is Dīpaṅkara with Sumāti (Schlingloff 2000/2013: No. 72), another our Buddha Śākyamuni with Rāhula (ibid.: Nos. 70-71) – two pictures, which appear to be connected both in the Ajanta paintings and several times in the Gandhara reliefs (cf. Taddei 1992; Vasant 1991 and 1992; Cohen 1995: 240f), and were certainly, in one way or another, jointly carrying a distinct message. In the original design, there were probably no additional Buddhas on the façade.

There were two unexpected observations that became apparent while working on Ajanta’s “devotional and ornamental paintings”:[2] first, that the representations of the Buddhas appear in the painted caves in very limited spaces only; second, that the non-narrative representations concentrate on auspicious pictures promising worldly prosperity – good fortune in business, money, and healthy children – and not on the Buddha or nirvāṇa.

The decoration of the caves illustrates two different complexes of themes. One of these is clearly Buddhist and is oriented towards the perfection of moral qualities, future lives, nirvāṇa or the Buddhahood; the second shows the mostly pan-Indian world of the genii and is oriented towards material prosperity in this life.

It is, of course, a doctrinal contradiction which characterizes both parts of the imagery; simply speaking, one who aims for nirvāṇa should not seek material wealth or bring children forth into the world. However, human nature wins over doctrine and does not care for religious justification. In the caves of the Buddha the yakṣas bestow rolling coins and frolicking children. This part of the caves’ decoration was certainly of no lesser importance then the visualisation of Buddhist dogma, and because of this should by no means achieve less attention. It is not easy to find a proper denotation for these two kinds of representations. It would be not proper to label all of the representations connected with material wealth as “profane” because the yakṣas and Kubera granting wealth are deities; that is, they are divine. They are, however, certainly less “divine” than representations of the Buddha and of all of the topics connected with his teaching.

It appears to the present author that the best way to differentiate between these two kinds of representations is to define the various characteristics of the divergence between the two categories from a soteriological perspective and to label them as either “relevant for enlightenment” or “irrelevant for enlightenment” (Zin 2015).

It is no deviation from the entirety of Buddhist art that, in the representations in Ajanta, both what is relevant and what is irrelevant for enlightenment have been placed directly alongside one another. As we are still able to view these representations in situ, their differences are at times quite striking – the best example being the yakṣas’ shrines on both sides of the Buddha’s cella in Cave II. What is also remarkable is that these yakṣas – like the pair discussed earlier on the façade of Cave XIX – are equipped with features that are, in fact, “relevant for enlightenment”. As one can see, the differences seem to melt away.

It appears that it is indeed possible to reveal the intended programme of Ajanta’s painted monastery caves, even when bearing in mind that not a single cave is wholly preserved, and that no such thing as a “typical cave” exists today or likely ever existed.

We should take note of the fact that the paintings in the old caves even now exhibit an order to the topics depicted. In Cave IX, the traces of the narrative paintings are unfortunately preserved only in the front section of the interior (Schlingloff 2000/2013: Nos. 1-5, 10). The preserved section displays jātakas on the left side wall, and a story which takes place during the life-time of the Buddha, the narrative about the nāga Erakapatta, on the right. The front wall of the cave with the entrance door displays the narrative of Paṇḍara – a jātaka about the nāga, as if bridging the transition between the jātakas on the left and the nāga story on the right. The importance of the Paṇḍara narrative, which tells about the nāgarāja protecting himself and his people against the garuḍa, or perhaps of Paṇḍara as a protective snake deity, is not understood, but it should be noted that the same nāga (inscribed: nāgarāyā paḍarako, cf. Nakanishi / von Hinüber 2014, II.8,1, pl. 28, p. 82), represented in zoomorphic form (Poonacha 2011: pl. 118), was placed in front of the northern entrance to the stūpa enclosure at Kanaganahalli. The sequence of the massive slabs which covered the dome of the Kanaganahalli stūpa makes it evident that the slabs were grouped thematically – there are groups with the jātakas, with scenes from the life-story of the Buddha, and with narratives about the Buddha’s contemporaries, playing out during his life-time. The Kanaganahalli slabs, which can not only be dated ca. contemporarily with the old Ajanta paintings, but which also display several thematic and formal similarities to the paintings, are begging for comparison. The pictorial programme of the paintings in Cave X in Ajanta (Schlingloff 2000/2013: Nos. 6-9), especially, reveals parallels with Kanaganahalli, as the thematic groups of the paintings are clearly visible here, with the right side wall being used for jātakas, the left for scenes from the life-story of the Buddha, and the wall in the apex behind the stūpa for the story of King Udayana and his wife Śyāmavatī, the pious follower of the Buddha. The narrative of Udayana and Śyāmavatī is represented in Kanaganahalli as well (Poonacha 2011: pl. 72-73; Zin 2011, figs. 7-8).

While the fragmentary paintings in Ajanta that were only preserved in caitya caves do not allow for general conclusions about their ordered programme, they make evident that a grouping of the represented topics was intended.

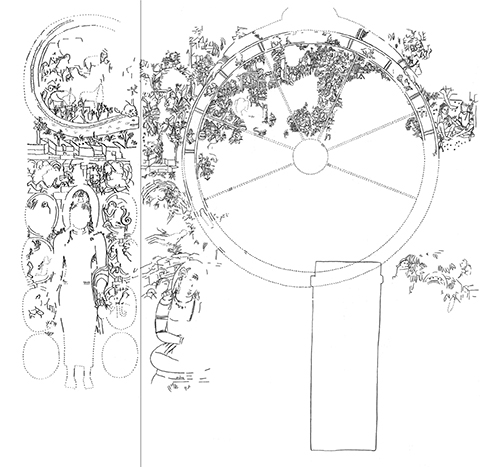

Concerning the painted caves from the 5th century (here, we can only examine what are known as the vihāras) the order of the depictions was intended as follows: The walls on both sides of the entrance to the cave, and of the entrance to the antechamber of the sanctuary and to the sanctuary with the Buddha were covered with depictions of rocky landscapes, populated by different genii with a dominating figure of a king, usually understood to be a Bodhisatva (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): Nos. 42-43). Together with the pair of the sculptured Bodhisatvas attending the Buddha in the sanctuary, there were eight kings in the Buddha’s entourage, six of them painted surrounded by genies on the walls parallel to the façade. The axial-symmetrical placing of these paintings and their mirror-inverted composition manifest the thought-out design of the entire decoration of the caves.

The multiscenic jātakas, scenes from the Buddha’s life-story and narratives of his contemporaries, were placed on the front-, side-, and rear-walls of the veranda and the main hall (Schlingloff 2000/2013: Nos. 11-79). When the person of the Buddha appears in this part of the cave decoration it is within the narrative representations.

A particular mode of representations, as if making a path between the narrative paintings in the hall and the main image of the Buddha in the sanctuary, are paintings on the side-walls of the antechamber. As the still-preserved walls in Caves I, VI, and XVII show, the paintings – the Māravijaya, the Descent from the Trāyastṛṃśa, and the Miracle of Śrāvastī (Schlingloff 2000/2013: Nos. 80, 86, 88, 90, 92) – are of a narrative character, but of an axial-symmetrical composition and a conflated manner of representation. The Buddha in the middle transforms the character of the pictures from the narrative to the devotional.

The special character of such scenes and the importance of their placement in the area of the sanctuary manifests itself in the representation of the Buddha’s life-story in Cave XVI (Schlingloff 2000/2013: No. 64). The painting shows the events over more then 30 episodes, beginning with the sojourn of the Bodhisatva in the Tuṣita Heaven, before he was born as Siddhārtha, and leading up to the First Sermon. However, the two most important scenes, the Enlightenment – i.e. the Māravijaya – and the First Sermon, are not (and never were) there. The visitor of the caves must have known that such main events were not to be expected in the hall, among the narrative representations, but rather in the nearest vicinity of the sanctuary, or even in the sanctuary itself. The question must namely also be raised as to whether the main Buddha of the sanctuary should not also be understood in a particular narrative context – the representations of many Buddhas on the walls of the cellas or of the mango tree above the Buddha in Cave XX (Fig. 6) suggest that, at least in these cases, the central Buddha might be read as performing the Miracle of Śrāvastī. But these Buddhas are first of all objects of devotion, symbols of the presence – hic et nunc – of the Buddha with his teachings and his blessings.

Fig.6

Comprehending the premeditated placements of the paintings in the caves can help to understand them and also to recognize the continuation of the earlier pictorial tradition, with its groupings of topics. Of special importance in this matter are the paintings of the rocky landscapes with the kings, flanking the entrances.

Fig.7

Fig.8

The tradition of depicting mountains at the entrances is an old one and is not limited to the Buddhist temples (Fig. 7);[3] the most beautiful example has been preserved at the toraṇa architrave in Stūpa III in Sanchi (Fig. 8),[4] where a god holding a vajra (in Sanchi, it is not necessarily Indra) is represented surrounded by different genii, nāgas, composite creatures, half-human, half-bird, horse-headed women, musicians with vīṇās, what are likely gandharvas, wild hunters (the only representatives of humans here), and a pair of yakṣas, the male with a money bag and the female with a child. The representations of the romantic, mysterious landscapes correspond with the topoi of Indian imagery as a whole; e.g. the description of the slopes of Himālaya in the opening section of the Kumārasaṃbhava with mysterious Śabaras and different kinds of hybrid beings such as kinnaras, half-human, half-bird, or women with horse heads – being the most charming example.

To the present author, the paintings of the romantic rocky landscapes at the entrances in Ajanta caves represent a continuation of the old tradition and have much to do with the old pan-Indian belief that if someone wants to reach heaven, he must cross the Himālayas, the passage between the world of humans and that of the gods. Such imagery corresponds directly with an understanding of the Four Great Kings (Catur-Mahārāja) whom the Buddhist tradition understands as commanders of different genii.

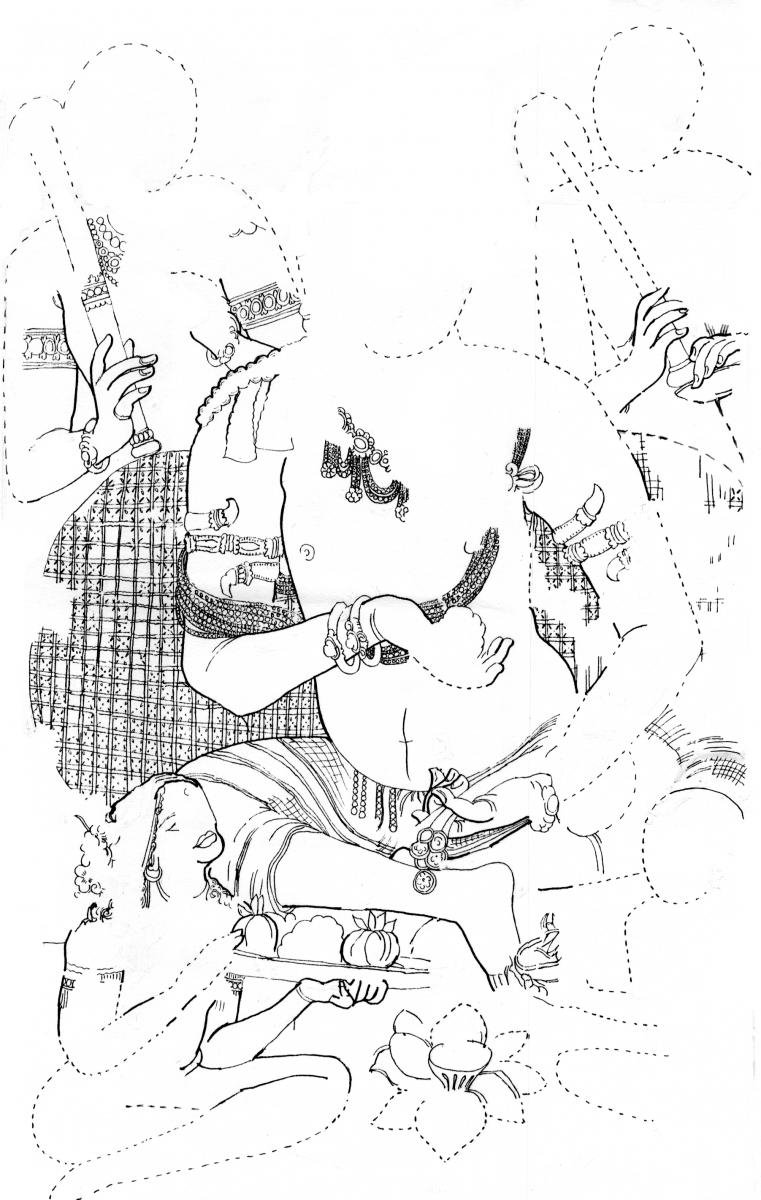

Fig.9a

Fig.9b

The oversized kings in the rocky landscapes in Ajanta (Fig. 9 a-b)[5] are usually explained as Bodhisatvas. This can not be denied even if they are, first and foremost, imbued with the earlier imagery of the leaders of the genii. It is worthwhile to stress that the kings dominating the landscapes do not exhibit the iconography of the Bodhisatvas, such as Avalokiteśvara, which was well known in the Ajanta caves, but instead demonstrate some features which are not to be met again: The most famous of the “Bodhisatva Kings”, located on the right side of the entrance to the antechamber in Cave I, bears a little figure without a head on the front of his crown (Fig. 10 a-b).

Fig.10a

Fig.10b

One could imagine a broken model which the painter might perhaps have carelessly copied; this is, however, not the case, as the crown of one Bodhisatva King in Cave II (who is, in fact, standing in the same position to the right of the entrance to the antechamber) likewise displays a strange, squatting person, apparently without a head (Fig. 11 a-b-c).

Fig.11a

Fig.11b

Fig.11c

Fig.12

This little figure calls to mind pictures of the yakṣas from the same cave (Fig. 12).[6] At the present state of knowledge, an explanation for this peculiar representations cannot be given – this is no different from the elusive unambiguous explanation for the “Bodhisatva Kings”. It appears to the present author that research should lead in the direction of the yakṣas rather than the Bodhisatvas; after all, it must be always remembered that the vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādins which, as Schlingloff has shown, was the literary basis for a great part of the narrative paintings, speaks about painting a yakṣa image at the entrances to the monasteries and of a yakṣas holding a garland at the entrances to the gandhakuṭīs, i.e. Buddha’s cells.[7]

Nāgas play an important role in Ajanta, possibly due to the location of the caves in the river ravine. It is, of course, merely speculation, but it is easily imaginable that the nāgas were present earlier, and that the site was a sanctuary of the snake deities before Buddhist monks were settled here. Unfortunately we do not know the personal name of the nāga of the site. As for the yakṣas, they were, of course, very important as well; it is of course very possible that the local beliefs were manifested in the decoration of the caves. The special role of Hārītī in Ajanta may have been overestimated (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 25); the narrative of the conversion of the murderous, child-thieving yakṣiṇī who turns into a protector of children, is in fact depicted here – in the upper part of the back wall in the Hārītī chapel in Cave II – as the story is rendered in the literary tradition of the Mūlasarvāstivādin and is also represented several times in the paintings of Central Asian Kucha, where the same Buddhist school was also present (Zin 2006: No. 2). Representations of Hārītī – or rather a goddess surrounded by children that we usually label with her name – were popular in entirety of India, so it would be strange if she were not represented here. It is not easy to ascertain who the partner of Hārītī might be; the texts tell us of a general of the yakṣas by the name of Pañcika, but there is nothing in his appearance in Ajanta that distinguishes him from Kubera.

Fig.13a

Fig.13b

Kubera is present in Ajanta (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 30). The most beautiful painting of a yakṣa (Cave XVI, front aisle, right side) shows Kubera (Fig. 13 a-b)[8] which we know because there is – or at least was when a copy was made in the 19th century[9] – a big lotus flower in front of him, as well as the padma together with the śaṅkha (conch-shell), belong to Kubera’s important attributes; they are his “treasures”, or nidhis. The painting might be exceptionally beautiful but the iconography is not exceptional, and does not differ from imagery used in various other locations in India.

Fig.14

Much more interesting are two male yakṣas in the shrine to the viewer’s left in the sanctuary in Cave II (Fig. 14). The explanation, that the yakṣas are Padmanidhi and Śaṅkhanidhi, is not a suitable one. Kubera’s nidhis (“treasures”) are often shown as personifications, but they never take the form of adult deities enthroned and adorned with nimbi. Padmanidhi and Śaṅkhanidhi were popular in Andhra – the most beautiful representations of them were found in Nagarjunakonda (Figs. 15-16)[10] – and they appear in Ajanta ceiling paintings as well (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 22).

Fig.15

Fig.16

The two yakṣas sitting at a height level to each other appear in Ajanta – excepting the chapel in Cave II and in reliefs in Caves I and XXIII – and in Cave III in Aurangabad. It seems that the worship of the two yakṣas, apparently brothers (since they are sitting at an equal height one cannot be subordinated to the other), was exclusive for the area. The present author gave the tentative explanation of the yakṣas as brothers Māṇibhadra and Pūrṇabhadra (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 29), who are often mentioned in literary works together. About Māṇibhadra it is said that he looks like Kubera – which quite exactly corresponds with the representations in Ajanta and Auragabad, as one of the yakṣas is always represented with a money bag from which coins are rolling. The interpretation of both yakṣas as brothers Māṇibhadra and Pūrṇabhadra is quite possible, although far from certain.

Since the representation of the two yakṣa brothers is nonparallel, could a scrutiny of the texts (Purāṇas?), which call on two yakṣas in connection with a particular geographical place, perhaps be the key to ascertaining the historical name of Ajanta? The Mahāmāyurī connects Maṇibhadra and Pūrṇabhadra with the town Brahmāvatī, which was, however, connected to Gandhara.

Fig.17

Fig.18

Of the yakṣa Māṇibhadra in Ajanta a certain depiction is given (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 28). He is represented (Fig. 17) on the left side wall of the veranda in Cave XVII, underneath the Wheel of Rebirth (Saṃsāracakra) and clearly inscribed: Māṇibhadra. The Saṃsāracakra (Fig. 18) is certainly among the most impressive paintings of the site, but no less attention should be given to its surroundings, which correspond quite precisely with a description, a sort of set of instructions on how to paint the Wheel, which survived in a Sanskrit manuscript found in Central Asia (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 46; Zin/Schlingloff 2007). The right side of the Wheel’s surroundings which represent the fourfold Māra matches precisely with this text.

The left side of the Wheel, together with the painting on the veranda’s front wall which continues into the Wheel, directly connecting with it on the left, works more by means of an associative visual language as an illustration of the text (even though one of the physicians mentioned in the text appears here, depicted seated over the corpse of a person he could not cure) and represents different aspects of the human wandering – which should certainly underline the essential wandering through different rebirths inside of the Wheel. It is interesting to focus on the elements of the depiction in order to understand of the role of the yakṣa Māṇibhadra in this context.

Fig.19

The arrangement of the paintings is, namely, meaningful: The upper part of the front wall shows a jātaka story (Fig. 19).[11] It is the Siṃhāvadāna (Schlingloff 2000/2013: No. 24), the narrative about a lion who helped a group of merchants to escape from being killed by a giant snake.

Fig.20

Below, Avalokiteśvara the Saviour (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 44.4) is shown, surrounded by scenes of eight different perils (Fig. 20), signalizing that one can call him for help when one falls on hard times. The representations of perils primarily concern dangers in the wildness and on the sea, i.e. perils which are encountered by the wandering traders.

Fig.21

The painting continues on the side wall (Fig. 21), stretching out towards the Wheel of Rebirths: The wandering merchants appear to be the same as those who escaped from death by giant snake, and Māṇibhadra to the right of Avalokiteśvara, who aids at times of peril, must be seen as the guardian of the wanderers – which, in fact, he truly is (references in Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 28): The yakṣa Māṇibhadra (Maṇibhadra or Māṇicara) was a powerful deity of Old India, and the inscriptions allow us to recognise him in several sculptures, as in the famous yakṣas from Parkham and from Pavaya. There are other inscriptions which refer to him as “caravan leader”, and still others providing information about donors who gave to Māṇibhadra; they belonged to the merchants’ guilds. Finally, there are different statements which can be found in literary sources, among others in the Mahābhārata (III.61.122-123), which allow us to recognize Māṇibhadra as the protector of the traders.

In this part of the pictorial decoration of Cave XVII (Fig. 21) we meet with the fourfold imagery, with each part of it a very different type and all illustrating the same topic. There is a jātaka story from the Buddha’s former life about saving wandering merchants from deadly peril, and there is a Buddhist deity incorporated into Mahāyāna pantheon – the saviour Bodhisatva coming in the hour of need to the wandering traders. There is the visualisation of the Buddhist doctrine with the wandering of beings through all realms of existence in the Wheel of Rebirths (according to a Hīnayāna manuscript), and there is a pan-Indian yakṣa Māṇibhadra, the protector of the traders.

It may well be that the significance of the painting was different for different visitors of the caves: the merchant would understand that Avalokiteśvara and Māṇibhadra would help him on the road, while the monk, familiar with the texts, would conclude that Avalokiteśvara, who liberates one from passion (rāga), hate (dveṣa), and stupidity (mohā) (Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra, ch. 24, prose), could help to stop the turning Wheel, as the description directs the painting (… madhye rāga-dveṣa-mohāḥ kartavyā rāgaḥ pārāvatākāreṇa dveṣo bhujaṅgākāreṇa mohaḥ sūkarākāreṇa … cf. Zin/Schlingloff 2007: 92) of the symbols of the capital sins of the mankind – pigeon (passion), snake (hate), and pig (stupidity) – which keep the Wheel turning in the wheel-hub. The centre of the painting of the Wheel of Rebirth has been damaged but the three symbols must have been present there, as they are always repeated in the Tibetan, Mongolian, Chinese, and Japanese representations.

The fourfold imagery flows together and any differentiation of the topics into those that are relevant and those that are irrelevant for enlightenment vanishes.

In some other places in the paintings of Ajanta we can see that the yakṣa topics complete or conflate representations relevant for enlightenment; such as the abovementioned Kubera in Cave XVI (Fig. 13), who is surrounded by the representations of jātakas (Schlingloff 2000/2013: Nos. 12, 17, 21, 36), which all take place in the mountains (or at least in the landscape) – the imagery which corresponds closely with Kubera, as ruler of the northern side of the world, and as spokesman of the Four Great Kings on the slopes of Sumeru.

Generally, however, the representations of the world of the yakṣas and other genii are set apart from the other paintings because of the fact that they are represented in different places; as stated earlier, they can be found on the sides of the entrances, as well as on the ceilings, pilasters, and pillars.

In the rocky landscapes at the entrances, beautiful yakṣas, dwarves, gajakarṇas (dwarves with elephant ears), kinnaras (half-human, half-bird), sword-carrying vidyādharas, music-playing gandharvas, and indigenous wild hunters (as the only representatives of humans) appear (Zin 2003a/(in preparation): Nos. 27, 17, 20, 19, 16, 15, 21) – all these are present in pairs, while brahmakāyikas (ibid.: No. 33), the deities of the body of Brahma, are only male. In the decorative paintings on the ceilings, the same kind of yakṣas, dwarves, gajakarṇas, kinnaras, vidyādharas, gandharvas, and brahmakāyikas appear on pilasters and pillars, as well as nāgas, “northern” clad drinkers, sadāmatta (“always-drunk”) and karoṭapāṇis (“jar-in-hand”), dwarves with a second face on their stomachs, a woman with a horse’s head, aśvamukhī, and dwarves pouring out coins from sacks they carry or from their own heads (ibid.: Nos. 12, 31, 18, 24, 22).

While beholding the romantic rocky landscapes, it might appear that the genii are there to praise the Buddha – most of the genii pay attention to their consorts only, but they are, at the very least, grouped around the Bodhisatva Kings who are flanking the way to the Buddha’s shrine. The genii on the ceilings are more often seen in close vicinity to coins being poured out by dwarves, or different sorts of symbolical representations of fertility and opulence – such as Kubera’s treasures padma- and śaṅhka-nidhis or the vases of abundance (pūrṇakalaśas) – so that their role might rather be better defined as suppliers of luck and wealth to the visitors of the caves. Interestingly, the message of fertility and the auspicious symbols have made their way into even the tiniest elements of the ornamental decoration. Minute conch-shells appear in the in the geometrically ornamented panels. Sometimes a flower with four petals bears the semblance of being somehow asymmetrical – which is extremely unusual in these perfectly painted caves! Yet when we look closer, it becomes clear that this is not a flower, after all, but rather a composition composed of four minute conch-shells (Fig. 22).

Fig.22

Were the visitors of the caves interested only in attaining happiness in life, and not in the Buddha and nirvāṇa? This is certainly not so. They were coming to the caves to see the illuminating and edifying paintings, to hear the sermons of the wise monks and to pay homage to and to donate to the Buddha, the dharma, and the monastic order. Nevertheless, these were people from worldly walks of life, certainly often pilgrims, but mostly merchants on their trading routes, who were and would be exposed to all sorts of perils, and who sought the blessing of both Buddha and yakṣas for their onward journey and in order to attain economic rewards in return for their efforts. Who conceptualized the programmes of the paintings in the cave? We can only conclude that it was somebody familiar with the narrative tradition of the Mūlasarvāstivādins. He created interiors covered with illustrations of the compelling stories, making sure that the pictures changed from the narrative in the hall to the devotional as they approached the sanctuary, preparing the visitors to meet the Buddha in the gandhakuṭī. He was quite aware that the visitors would expect deities whom they could call on for help while they were on the road.

The “intrusive” paintings and reliefs, added to the “program” by the individual donors wherever space was still available on the walls, destroyed the order originally intended in the initial design. However, these pictures reveal a thought-provoking fact: there is neither a single yakṣa or nāga among them, nor a single jātaka; the intrusions depict solely Bodhisatvas and Buddhas. There are adorations of the Buddhas, rows of the Buddhas, series of rows of the Buddhas, and onward and onward; the Buddhas continue in rows and series, and what we are presented with is only that which is relevant for enlightenment.

Bibliography:

Cohen, R.C., 1995, Setting the Three Jewels: The Complex Culture of Buddhism at the Ajaṇṭā Caves, Diss. University of Michigan.

Nakanishi, M. / von Hinüber, O., 2014, Kanaganahalli Inscriptions = Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University for the Academic Year 2013, vol. 17, Suplement, Tokyo.

Poonacha, K.P., 2011, Excavations at Kanaganahalli (Sannati, Dist. Gulbarga, Karnataka) = Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India 106, Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Schlingloff, D., 2000, Ajanta – Handbuch der Malereien / Handbook of the Paintings 1. Erzählende Wandmalereien / Narrative Wall-paintings, Wiesbaden.

Schlingloff, D., 2013, Ajanta – Handbook of the Paintings 1. Narrative Wall-paintings, New Delhi: IGNCA.

Soper, A., 1950, Early Buddhist Attitudes toward the Art of Painting, in: Art Bulletin, 32, New York: 147-51.

Spink, Walter M., 2009, Ajanta: History of Development, Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Year by Year, HDO series, Brill: Leiden and Boston, vol. 4.

Taddei, M., 1992, The Dīpaṃkara-jātaka and Siddhārtha’s Meeting with Rāhula, How are they Linked to the Flaming Buddha?, in: Annali dell’ Istituto Universitario Orientale 52: 109-11.

Vasant, S., 1991, The Cult of Dīpaṅkara Buddha at Ajanta, in: The Art of Ajanta, New Perspectives, ed. R. Parimo (et al.), New Delhi: 151-55.

Vasant, S., 1992, Dīpaṅkara Buddha at Ajanta, in: The Age of the Vākāṭakas, ed. Ajay Mitra Shastri, Delhi: 209-18.

Yazdani, Ghulam, 1930-55, Ajanta, The Colour and Monochrome Reproductions of the Ajanta Frescoes Based on Photography, 1-4, Oxford (repr. New Delhi, 1983).

Zin, M., 2003a, Ajanta – Handbuch der Malereien / Handbook of the Paintings 2: Devotionale und ornamentale Malereien, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Zin, M., (in preparation), Ajanta – Handbook of the Paintings 2: Devotional and Ornamental Paintings, New Delhi: IGNCA.

Zin, M., 2003b, Guide to the Ajanta Paintings, 2, Devotional and Ornamental Paintings, New Delhi.

Zin, M., 2006, Mitleid und Wunderkraft. Schwierige Bekehrungen und ihre Ikonographie im indischen Buddhismus, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Zin, M., 2011, Narrative Reliefs in Kanaganahalli – A Short Outline of Their Importance for Buddhist Studies, in: Marg 63.1: 12-21.

Zin, M., 2015, Pictures of paradise for good luck and prosperity: Depictions of themes irrelevant for enlightenment in the older Buddhist tradition (with special reference to the paintings of Ajanta), in: Mani-Sushma, Archaeology and Heritage (Dr. B.R. Mani Festschrift), ed. V. Kumar, B. Rawat, Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation, 1-3, vol. 1: 125-47, pls.: 49-56.

Zin, M. / Schlingloff, D., 2007, Saṃsāracakra, Das Rad der Wiedergeburten in der indischen Überlieferung, Düsseldorf: Haus der Japanischen Kultur (EKŌ).

[1] If not otherwise noted, the photographs from Ajanta caves in this paper stem from Andreas Stellmacher, and were taken with the kind permission of the Archaeological Survey of India; drawings by the present author were published in Zin 2003a and 2003b. References to Ajanta – Handbook of the Paintings (I, Schlingloff 2000/2013 and II, Zin 2003a/(in preparation)) lead to comprehensive literary and pictorial representations, comparative material, and previous research.

[2] Zin 2003a, the book is currently in the process of being translated into English. The translation is financed by the IGNCA and shall appear as its publication in the nearest future.

[3] Udayagiri (Orissa), Ranigumpha, photograph by Caren Dreyer.

[4] Sanchi III, lowest architrave of gateway, photograph by Gudrun Melzer.

[5] Cave II, veranda, left from the entrance door.

[6] After Yazdani 1930-55, 2: pl. 48d.

[7] Analysis in Soper 1950: 149; Zin 2003a/(in preparation): No. 27, fn. 1, with quotation.

[8] Drawing by Matthias Helmdach.

[9] Copy by Griffiths 16g India Office London, vol. 72, no. 6026[3679].

[10] Nagarjunakonda, Archaeological Site Museum, Nos. 11-12, photographs by Wojtek Oczkowski with the kind permission of the ASI.

[11] Copy by Griffiths 17a, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, Indian Section, Mo. 136-1885; photograph in Institut für Indologie und Tibetologie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich.