The Ajanta cave paintings are admired all over the world. Recently, UNESCO declared the caves a World Heritage Site. Scholars like Ananda Coomaraswamy, A. Foucher, J. Griffith, G. Yazdani, M.N. Deshpande, D. Schlingloff, Karl Khandalawala, M.K. Dhavalikar and Walter Spink have devoted their lives to writing volumes on the Ajanta cave paintings, and this research has been made available to researchers, students and art lovers. Personally, I am grateful to all of them. However, while studying their works, I realised that most of these scholars have analysed these paintings from the viewpoint of art, history or religion, and have very rarely identified the paintings.

As a professor of Pali, I have been studying the Ajanta cave paintings for more than three decades. My approach has been threefold: identify the paintings; rectify misinterpretations; and observe the theological progress of Buddhism. I reviewed all the paintings1 and identified the paintings that had not been identified previously. Some paintings had been misinterpreted earlier; I interpreted them correctly. Though all these paintings are believed to be based on the Pali jātakas, I have found that some are based on the Avadāna—or texts written in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit (BHS), such as Mahāvastu Avadāna and Divyāvadāna—and on pure Sanskrit texts such as Ārya Śura’s Jātakamāla and Aśvaghośa’s Sundarananda Kāvya and Buddhacaritam. But scholars have not considered these sources.

The Ajanta caves were established between the second century BCE and about the eighth century ACE; so, the books of the Mahayana or the Vajrayana traditions, which were written later, are not relevant to our study. By the eighth century ACE, the Ajanta Caves were cut off from main society; only tribal dwellers (Ādivāsi) visited them regularly on certain festival days2. They did not, unfortunately, pay attention to the wall paintings of the Ajanta Caves, and developed their own tradition of painting—Warli— which has become popular across the world.

Who painted the panels of the caves at Ajanta? Though some believe that Buddhist monks or householders made the paintings, these were painted by guilds of painters from Maharashtra and, especially, Aurangabad. The members of these guilds were not necessarily Buddhist; they were also Hindus and Jains. Religion was not a criterion for appointment as a painter; preference was given to families that had been painters for generations. The minute details in the paintings, such as in the painting of a Brahmin performing pujā for the statue of the Buddha, in cave number 6, prove this.

The Mahāvagga (Vinaya Pìtaka) informs us that Theravādin monks would visit caves in different regions and tell the chief of the guild which Jataka Kathā to paint, but leave it to the chief to decide which events in the tale the painters should paint. The painters were free to paint as they liked. This is one of the reasons why the Ajanta paintings look alive, attractive and appealing. Some monks would supervise the job and pay the chief of the guild; the chief would distribute the money among the painters. Theravādin monks not only supervised the painting of the Ajanta caves but also contributed financially towards it. We, therefore notice that the paintings and sculptures in the caves at Ajanta, Pitalakhore, Bhājā, Beds and Karle are similar.

Paintings based on texts written in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit and pure Sanskrit can be observed in cave numbers 1, 2, 6, 7, 10, 11, 16, 17, 19 and 26. There are 18 such paintings; these are listed below, along with their sources.

Cave no. 1

- A lady reclining on a couch Sundarananda Kāvya

- Princess Mālini and Buddha Mahāvastu Avadāna

- King Śibi Mahābhārata

Cave no. 2

- The mythical world of Nāgas Mahāvastu Avadāna

- Purna Avadāna Divyāvadāna

Cave no. 6

- A bhikshu (?) A Brahmin Upāsaka

- Buddha figures Mahayana tradition

Cave no. 10

- Arrival of the king (Aśoka) to worship the Bodhi tree Edicts of King Aśoka

- Elephant with six tusks Chaddanta-jātaka, Mahāvastu Avadāna

Cave no. 16

- Hasti Jātakam Jātakamālā (a text written in pure Sanskrit)

- A dying princess Sundarananda Kāvya

- Conversion of Sundarananda Sundārananda Kāvya

Cave no. 17

- Group of six heretics Divyāvadāna

- A toilet scene, Princess Sundari Sundarananda Kāvya

- Prince Sundarananda, bewildered Sundarananda Kāvya

- The Buddha with Yaśodharā and Rāhula Mahāvastu Avadāna

- Sinhala Avadāna Divyāvadāna

- Enigma of flying horse Valāhaka jātaka, Mahāvastu Avadāna

We will study a few of these paintings.

Cave no. 1: Mālinīvastu -Māhavastu Avadāna (Baghchi, 2003)

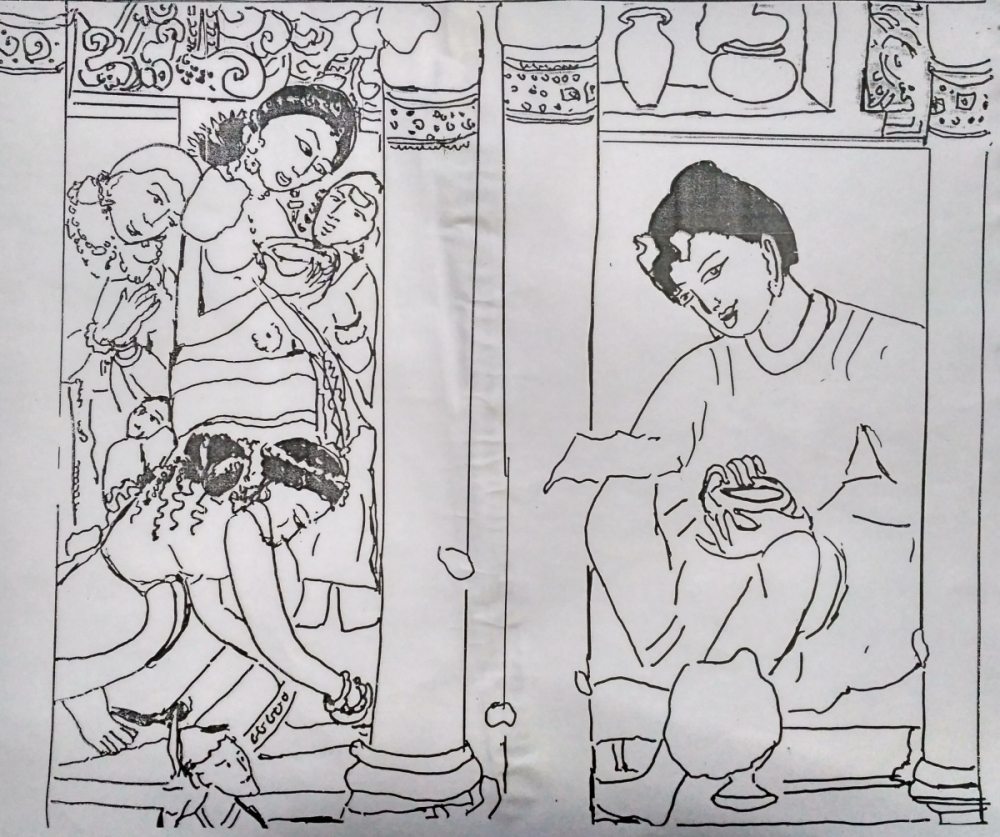

On the right side of the cave, on the back aisle, a scene of Princess Mālinī and the Buddha is painted on the wall above the door of the second cell (Fig. 1). There is a pillared hall divided into three sections. In the first section, a lady is seated on a couch. Her mood is pensive; two maids stand beside her. In the next section, the same lady kneels at the feet of the Buddha. He is seated; there is an alms bowl in his hands. The Buddha is shown in the third section. A maid, standing close to the lady, holds a pot in her hands. Another maid, standing behind her, clasps her palms in reverence. A third lady stands close to the secondmaid. Mālinī has placed her hands on the ground in reverence to the Buddha. She is well ornamented, and her coiffure is very beautifully decorated with flower garlands and beads. In the last section, the Buddha is seated on a stool; his feet are on the ground. He wears a samghāti and holds an alms bowl in both hands. He is looking at Mālini with compassion.

Fig. 1. Princess Malini paying homage to the Buddha

M.N. Deshpande (Ghosh, 1967) identifies this mural as a scene from the Mahājanaka Jātaka and the monk as Mahājanaka himself. Dr D. Schlingloff identifies the lady as Sumagadha (Schlingloff, 1999). I do not agree with either.

In the Pali jātaka, Mahājanaka renounced the world. His wife Sivali tried to dissuade him in many ways, but was not successful. She followed him until the forest, but owing to exhaustion, she fainted. Mahājanaka entered the forest, led a celibate life and reached the world of Brahma.

This scene is based on the Mahāvastu Avadāna. Mālini was the daughter of King Kruki of Banaras. She was very beautiful and dear to the king. He gave her the job of serving Brahmins. When she grew up, she realised that the Brahmins who came to the palace were full of lust (rāgagrāsticittassa), and not worthy of alms (Mālini samvicineti no time dakshinārah) (Bagchi, 2003). She started giving alms to Buddhist monks – Kāshyapa, Tishya and Bhāradwaja. Once, she requested them to invite the Buddha on her behalf. Buddha accepted her invitation and went to her palace along with his retinue of monks. After the meals, he admonished her and gave a religious sermon. This is the event described in this mural.

Cave no. 2: Purna Avadāna- Divyāvadāna

This scene is painted on the wall above the second and third doors in cave no 2 (Fig. 2). It is one of the popular Avadānas of the Divyāvadāna. The mural depicts various events from the life of Purna, a devotee of the Buddha. He had made six sea voyages; hence, the artists delineated seafaring scenes very vividly. It includes a sea storm, sea monsters, huge fish, sinking boats, Nagas and spirits. It is damaged and faded and almost invisible. On the third cell door, on the right, one can see the Buddha descending from heaven along with Arahanta. On the left, Purna, the merchant, bestows his wealth to the Buddha. This horizontal panel represents Dāna-pārami.

Fig. 2. Purna Avadana

This line drawing is based on G. Yazdani’s work. It is dim, indistinct and almost invisible. Yazdani is the only scholar who has studied the depiction.

Cave no. 10: Arrival of the king to worship the Bodhi tree - Edicts of King Aśoka

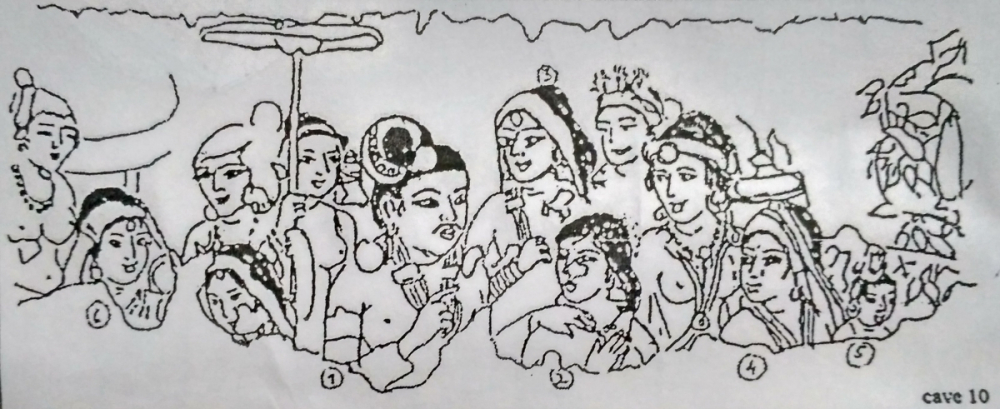

This painting is on the wall of the left aisle, behind pillar numbers 3 to 9 in cave 10 (Fig. 3). This is a very long panel. It depicts the arrival of a king with a group of soldiers and a group of women. In the midst of the panel, we observe that the king is accompanied by 10 ladies and two children. Then, we see a well decorated Bodhi tree. At the extreme right, near the Bodhi tree, another group of 16 ladies are standing. We will concentrate only on the middle portion of the panel, where the king is portrayed along with his retinue. The king is not wearing an elaborate crown, but a jeweled pin is fixed in his hair, and he wears a stringed pearl necklace that resembles the early sculptures at Sanchi and Bharhut. He has a moustache and is bare up to the waist. He seems to be saying something to a young boy, who is standing in front of him; the boy is looking at him attentively. Behind them, a lady is standing and looking at the king. Her head is covered with an upper garment that has a thick border, and a thick ring is peeping out on her forehead. Her ornaments are in the style of those at Sanchi and Bharhut. Beside her stands a lady, ornamented but not covering her head; she holds a pot in her hand. Below her and near the boy stands a lady looking at the queen. Her clothes and ornaments are similar to that of the lady standing between the king and the boy. Next to her is a small child wearing earrings and a hairpin.

Fig. 3. Arrival of king to worship Bodhi tree

I presume that this painting is based on the edicts3 of King Aśoka, which mention his visit to Bodh Gaya. This mural depicts King Aśoka with his queens and his retinue of female attendants and soldiers. The young boy listening to King Aśoka is Prince Kunāla, and the child at the other side is Prince Tivara. It is evident from King Aśoka’s rock and pillar edicts that he had visited Bodh Gaya to pay homage to the Bodhi tree. As it was a religious tour, the artists have not shown Aśoka with his crown. This mural depicts Aśoka saying something to Prince Kunāla, his favourite son. The woman standing between them is Queen Padumāvati, Prince Kunāla’s mother. The lady holding a pot in her hand may be the maid-in-chief. Next to her stands Queen Kāruvāki, also known as Tivaramātā. The child standing beside her is Prince Tivara. The two ladies in queen-like costume could be the queens of King Aśoka, and the one at the extreme right of the king could be Asandhimittā4.

According to M.N. Deshpande (Ghosh, 1967), caves 9 and 10 belong to the early middle second century BCE, close to King Aśoka’s reign (third century BCE). Buddhist devotees painted this panel as a token of gratitude to King Aśoka, who was a great patron of Buddhism. Besides, the costumes and jewellery of all the characters resemble the styles in Sanchi, Kausāmbi, Bharhut and Bodh Gaya. This helps us date this mural and cofddnfirm that the members of the Samgha might have taken the initiative of painting it.

Cave no. 16: The Dying Princess- Sundarananda Kāvya (Aśvaghośha)

This mural is painted in the left corridor near the pilaster and the front door (Fig. 4). It is based on Aśvaghośa’s Sundarananda Kāvya. Prince Sundarananda renounced the world. Saddened, his wife Sundari fainted when one of her maids showed her the crown on the day her husband was to be anointed king, and was laid on the bed. This event is depicted in the painting. She has lost vigour, and is being helped by her maids. One of them is holding her shoulders with both her hands; another maid is fanning her and one is holding a crown before her. A man, probably a physician, is giving her medicine to revive her strength. Two ladies in the backyard, standing near a banana tree, are bringing water in a pot. The artist has done justice to the situation, especially to the chapter Bhavyā Vilāpikā. Yazdani has aptly quoted J. Griffith: “For pathos and sentiment and unmistakable way of telling the story, this picture, I consider, cannot be surpassed in the history of art” (Yazdani, 1930-1955). It is laudable that poet and artist are at par – both have splendidly represented Sundari’s feelings. Truly, instead of “Dying Princess”, the painting should have been titled “Lovelorn Princess”.

Fig. 4. Dying princess

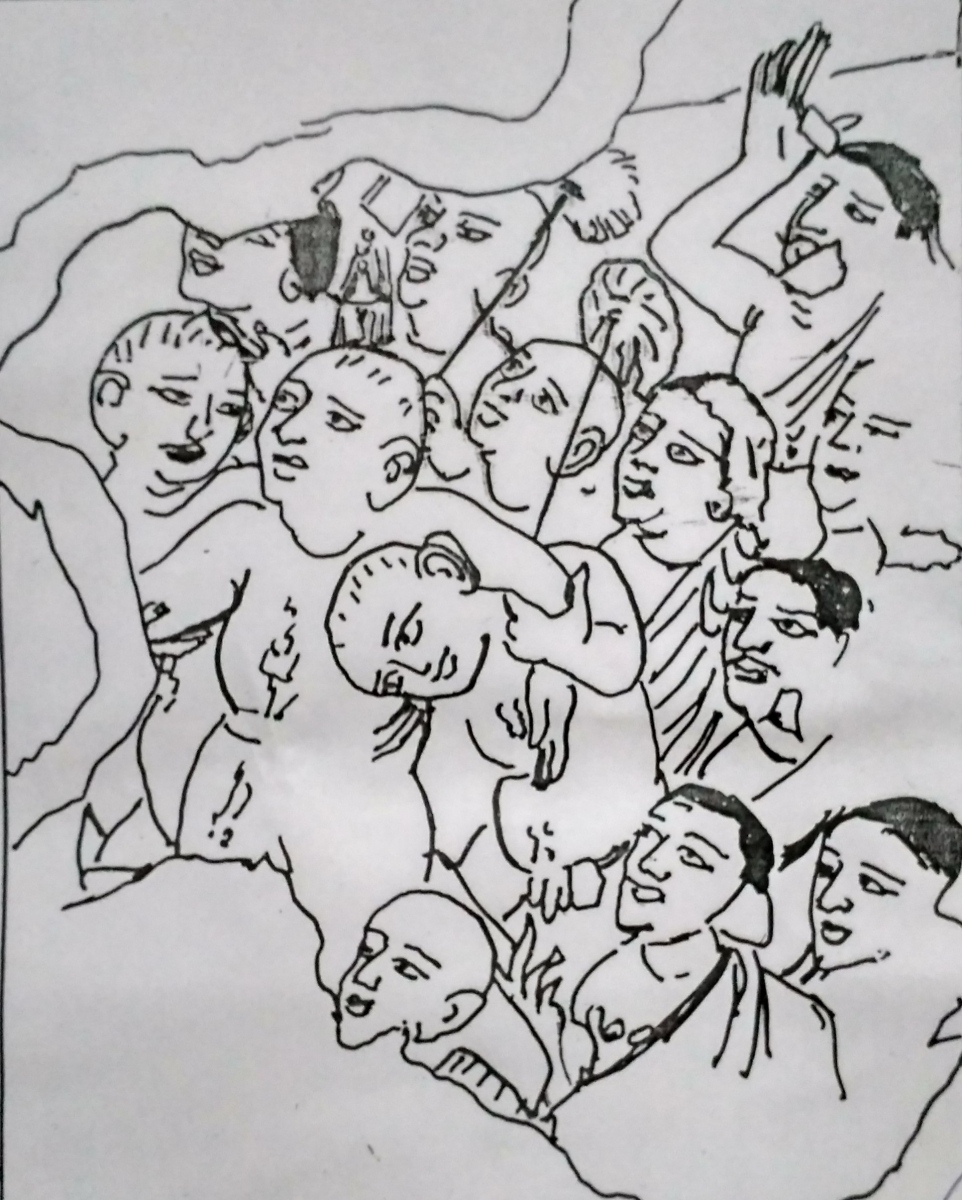

Cave no. 17: A Group of Heretics - Divyāvadāna

This painting is on the right wall of the antechamber in cave no. 17 (Fig. 5). There are thirteen figures of ascetics; four of these figures are naked. Behind them, two monks are holding chauris and bells in their hands. Next to them is a monk with a coarse cloth covering his left shoulder. Above him are two men; one with moustache, and the other has his right hand raised. The remaining three wear their shoulders bare; one of them has raised his fingers in an enquiring attitude. In his description of this mural, Foucher said “Some ascetics who were unfriendly to the Buddha wanted to challenge him” (Foucher, 1919-20).

The Divyāvadāna (Cowell and Neil, 1987) narrates: “At that time, six heretical teachers, being jealous of [the] Buddha and his popularity, challenged him, saying, ‘If monk Gotama performs one miracle (pratihāram) then we will make two, and if he performs two we will make four’ and extended the number to trible.” According to Pali texts, these six heretical teachers were Purana Kassapa, Makkhali Gośala, Ajita Kesakambali, Pakúddha Kaccāyana, Sanjaya Belatthi and Niganthanātaputta.

Fig. 5. A group of heretics

This mural is much damaged, and it is difficult to identify the six ascetics. In the first two, a fat man is naked, and is being helped by the other two naked monks. They seem to be marching in a procession. They may be Ājivaka monks who were as popular as the Buddha in the sixth century BCE. A similarly tonsured head of a monk, and part of his body, can be seen below them; he is looking towards the front. Beside him is a monk who wears his hair cropped; his right shoulder is bare, and his upper garment is on his left shoulder. He is looking towards the front and is making an enquiring gesture with his right hand. Near him stands a similarly dressed monk; they could be novice monks. Behind these two novice monks is a row of five monks. The first one, on the right, wears a moustache and cropped hair; his right shoulder is bare. The moustache indicates that he is not a Buddhist or Jain monk. Beside him stands a monk wearing a coarse upper garment that has a check pattern on his left shoulder; his right shoulder is bare. He wears his hair long, down to his neck, and is looking upwards. He may belong to the group of Ajita Kesakambali. Next to him stand two monks with tonsured heads; they are holding chauris in the hands. One of them is also holding a bell. They could be disciples of Niganthanātaputta (Jain monks). Beside them stands a monk whose face can be seen partially. He wears his hair long, down to his neck, and is holding something in his hand, but what he is holding is not clear. In the last row stands a monk, wearing hair and moustache, and raising his right hand in protest. His upper garment is on his left shoulder. Below him stands another monk wearing hair and looking upwards.

It is clear that all these monks are looking upwards at an object or person and are marching in procession. They look agitated. This is the only mural of heretics found anywhere. What could have been the motive for painting a group of heretics? W. Spink (Spink, 2009) claims it was painted in a single year, 471 AD, when the Mahayāna tradition held a powerful influence in the caves of Ajanta.

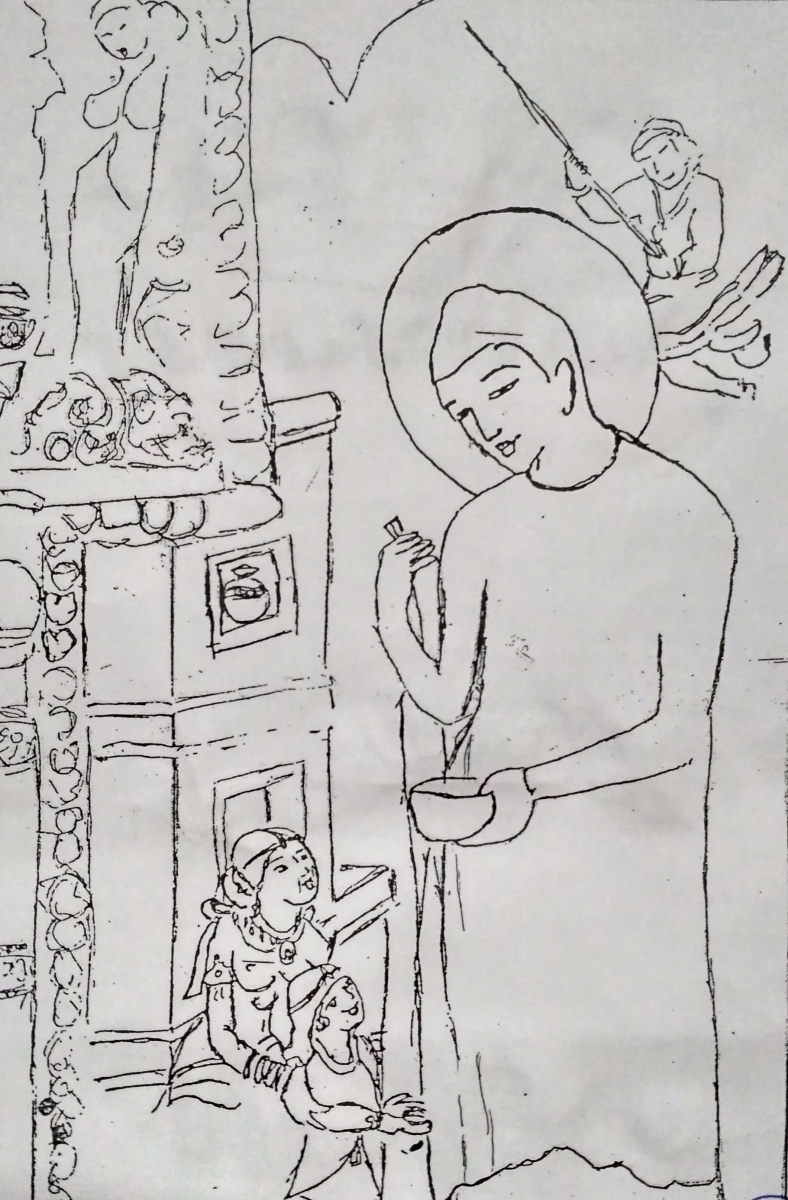

Cave no. 17: Buddha, Yaśodharā and Rāhula - Mahāvastu Avadāna

This mural is on the wall of the antechamber of cave no. 17, to the left of the shrine (Fig. 6).The Mahāvastu Avadāna narrates that King Śuddhodhana had decreed that no one should disclose the identity of the Buddha to Rāhula; anyone who did so would be put to death. But when the Buddha went to the palace, his shadow fell on Rāhula, who experienced a feeling of tranquility, and he asked Yaśodharā, “Oh, mother, can this recluse be any relative of mine?” (Baghchi, 2003) Moved, Yaśodharā decided “I will tell him even if they hack me with a sword.” She replied, “My son, he is your father.” Rāhula exclaimed, “Oh, mother, this one is my father!” Holding the corner of the Buddha’s garb tightly, Rāhula said, “Oh, mother, if he is my father then I shall follow the path of my father.” (Bhagavato civarakonake slista āha, “Ambe, yadi sea mama pitā bhavanti pitrukam mārgam anvesyām.”) (Basak, 2004).The artist captured this exact moment and painted it skillfully in this mural. This topic is a favourite of texts in both Pali and Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. At Ajanta, we notice two murals on this topic, in cave numbers 16 and 17, and as a sculpture in cave no. 19. The artists have drawn the figure of Buddha larger than those of Yaśodharā and Rāhula, to reveal his spiritual greatness.

Fig. 6. Buddha, Yashodhara and Rahul

This description solves the riddle of the child touching the corner of the samghāti of the Buddha. Yaśodharā, standing in front of the Buddha, is holding Rāhula with both hands, as if presenting him to the Buddha. She is delineated so beautifully that Yazdani writes, “This fresco is one of the finest portrayals of feminine elegance and emotions peculiar to the sex” (Yazdani, 1930-1955). Most scholars, like Deshpande, Griffith and Dhawalikar, say that this mural is based on the Pali Nidānakathā. I do not agree. In the Nidākanakathā, Yaśodharā tells her son Rāhula to follow the Buddha, who was going begging for alms in the streets of Kapilavatthu, and ask for his inheritance. Rāhula runs after the Buddha, saying “Give me my inheritance” (Dāyajja mam dehī). But this painting describes an entirely different situation. Second, Yaśodharā’s expression is serene, calm and pleasant, and not sad or reluctant (as per the Nidānakathā). Yazdani says that “Yasodharā has been shown in an appealing manner in which she is looking towards the Buddha with feeling of love first and reverence afterwards” (Yazdani, 1930-1955).Thirdly, the Mahāvastu Avadāna describes the child’s touching of the Buddha’s robe. That is the scene painted in this mural.

The paintings at Ajanta are based on texts datable to the 2nd century ACE; therefore, earlier Mahayānist trends can be observed in the murals of Ajanta.

Concluding reflections

Historical, archaeological and aesthetic aspects are important in research, but as guiding factors. These Above, we saw that six murals in five different caves are based on texts in Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit (Mahāvastu Avadāna and Divyāvadāna) and in pure Sanskrit (Jatakamālā and Aśvaghośha’s works).

Notes

1. See Ajanta Paintings Unidentified and Misinterpreted, Buddhist World Press, Delhi, 2013.

2. Shrikant Dabhade has worked on this topic for many years and has made great strides.

3. Aśoka’s edicts are mainly in Pali language.

4. For more details, see The Queens of King Aśoka, Indica, 1969.

Bibliography

Aall, Deshpande, Lall, and A. Ghosh, eds. 1967. Ajanta Murals: An album of eighty-five reproductions in color. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Baghchi, S. 2003. Mahāvastu Avadāna, vol. I. Darbhanga: Mithila Research.

Basak, R. 2004. Mahāvastu Avadāna, vol. III. Mithila Research Institute.

Foucher, A. 1919-20. ‘Preliminary Report on the Interpretation of the Paintings and Sculptures of Ajanta’, Journal of the Hyderabad Archaeological Society.

Neil, Robert Alexander and E. B. Cowell, eds. 1886. The Divyavadana: A Collection of Early Buddhist Legends. Cambridge University Press.

Schlingloff, Dieter. 1999. Guide to the Ajanta Paintings: Narrative Wall Paintings. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Spink, Walter. 2009. Ajanta: History and Development, vol. IV. Boston.

Yazdani, Ghulam. 1930-55. The Colour and Monochrome Reproductions to the Ajanta Frescoes based on Photographs and Explanatory Text (4 vols). London: Oxford University Press.