The meaning of mudra (gesture) in Sanskrit is mudam anandang rati dadati (‘that which gives ultimate joy’). Mudra has been an integral part of Indian heritage and culture since the Vedic period. It has been a part of rituals, dance and drama in India. Mudra, in itself, is a medium of practical knowledge. In every corner of the world, those engaged in Indian dance, yoga or Indian studies are fascinated by mudras and their use. Dancers are particularly inquisitive about mudras. In the Vedic period, while performing yagnas (sacrificial rites), priests and religious masters created mudras for ahuti (offerings), they also used mudras as an element of worship while reciting mantras.

Mythological sources say that the Natya Veda (the book on Dramaturgy) was created by Lord Brahma. According to these sources, Brahma gave the knowledge of the Natya Veda to Bharata Muni (or Bharata). Then, Bharata Muni, along with his 100 sons, performed three types of dramatic actions—verbal, grand, and energetic. Brahma also asked Bharata Muni to incorporate grace into this performance, for which it was necessary to include Nataraja’s style of dance. In fact, the use of dance is explained thus: ‘...it adds beauty and grace’ (Tarlekar 1999). This graceful recital gave birth to the sentiment of love. In order to incorporate erotic and romantic subjects, women and apsaras (celestial dancers) were included in the performance. It must be admitted that the mere enactment of heroic emotions and tales makes performances flat and bland. Therefore, mudras were used to portray erotic emotions, according to the traditional account of the Natyashastra.

According to another account, Shiva taught dance and performance to Nandikeshvara, the great theorist of Indian music and dance and the author of Abhinaya Darpana. Nataraja’s dance, known as tandava and sometimes considered a masculine form of dance, also involved mudras. Nandikeshvara gave this knowledge to Brahma, who asked Bharata to write the Natyashastra. Thus, according to the Natyashastra, Brahma is the source of natya (dance-theatre), Vishnu is the source of vritti (the constituent elements of drama), and Nataraja is the source of nritya (dance). Traditional sources say that Shiva requested Parvati to teach the soft and feminine form of dance to Usha, the daughter of the sage Vana. This form, known as lasya, also uses mudra.

Gesture or mudra is considered the soul of Indian classical dance. According to the Natyashastra, ‘the experts are to use the mudras according to the popular practice and in this matter, they should have an eye on their movement, objects, sphere, quantity, appropriateness and mode’ (Bharata 1995). The palm of the hand is a centre of expression. Showing the palm with various positions of the fingers is characteristic of classical dance. The wrist is the pivot for movement of the hands in any direction. The language of mudra is based on 24 mudras enumerated in the Natyashastra and 28 in the Abhinaya Darpana. Single-handed gestures are called asamyukta, and those that use both hands are called samyukta. Each mudra is described in these texts, with information on how the fingers should be extended, separated, or bent to form the specific mudra. In this context, it must be remembered that the synonym for mudra is hastavedah.

Theoreticians, scholars, critics and artists from Bharata Muni’s time to the present age have described mudras as the language of dance. Indeed, commentators like Nrityabaridhi Bela Arnab (1992), Anup Shankar Adhikari (1973), Nilratan Bandyopadhyay (1972), Gayatri Chattopadhyay (1995) and Krishna Acharya (1990) have chosen one simple statement—‘mudra is the language of dance’—to underline the indispensable significance of mudras. We can claim that the Indian classical dances—Bharatanatyam, Kathakali, Kathak, Manipuri, Odissi, Mohiniyattam, Sattriya and Kuchipudi—are repositories of mudras that invoke emotions and objects. An essential component of the Indian heritage of classical dances, mudras have been depicted with fervour in all ages of our creative history, telling and retelling stories through dance.

Nrityabaridhi Bela Arnab (1992) has also woven an umbilical link between Kathak and mudras to dispel the prevalent notion that mudras do not occur frequently in Kathak recitals. Questioning the conclusions of Krishna Acharya (1990) and Anup Shankar Adhikari (1973), she has argued that mudras and Kathak are inseparably bound and merge into each other when the kathak (storytelling) begins in the right sense of the term—that is, after the footwork and turns have been executed. We must recall what Bela Arnab has said in this regard, ‘Various gestures of the hand that express human emotions or depict objects are known as mudras. The dance artistes embody their 'bhavas' or feelings with the help of these tutored gestures. In short, mudras constitute the language or vocabulary of dance (Devi 1972:43).'

There is no disagreement among scholars on the use and application of mudras, although records of their numbers vary in the hands of different aestheticians. According to Bharata Muni, considered the founder of Indian aesthetics, there are 13 samyukta mudras (made with two hands) and 24 asamyukta mudras (made with one hand). Bharata Muni is quite categorical about this numerical division in the Natyashastra. However, Nandikeshvara, who came after Bharata Muni, states that there are 51 mudras in the dancer’s rich repertoire—28 of these are asamyukta mudras and the remaining are samyukta mudras.

The samyukta mudras in Bharata Muni’s Natyashastra are anjali (salutation), kapota (dove), karkata (crab), swastika, pushpaputa (flower basket), khatva (bed), bardhaman (crescent), utsanga (embrace), nishad (ending point), dola (swinging arms), makar (sea creature), gajadanta (tooth of elephant), and avhiksha (beyond sky); the 24 asamyukta mudras are pataka (banner), tripataka (triple banner), kartarimukha (scissor mouth), arala (bent), suktundo (parrot beak), musti (fist), shikhar (peak, crest), kapitha (wood apple), katakamukha (link), suchimukh (needle face), padmakosa (lotus bud), sarpasirsha (snake head), mrigosirsha (deer head), kangul (tail), alapadma (fully bloomed lotus), chatura (clever), bhramara (bee), hamsasya (swan face), hamsapaksa (swan wing), samdamsa (pincers), mukul (flower bud), urnanabha (spider), and tamrachuda (cock). Nandikeshvara’s additions to the asamyukta repertoire include simhamukha (lion face), chandrakala (crescent moon) among others. A popular mudra that is constructed and used frequently is pataka, which belongs to the asamyukta category; it invokes rivers, clouds, etc.

Following are the English translations of some more mudras -

Asamyukta mudras:

ardhapataka: half flag

mayura: peacock

ardhachandra: half moon

trisula: trident

bana: arrow

ardhasuchi: half needle

silimukha: crab face, female frog

Samyukta mudras:

Shivalinga: phallus

kartari swastika: crossed scissors

sankha: conch shell

chakra: discus

pasa: noose

kilaka: bond

matsya: fish

kurma: tortoise

varaha: boar

garuda: eagle god

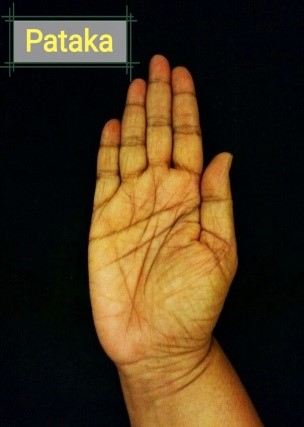

Following are images of a few asamyukta mudras:

Fig. 1: Pataka - All five fingers are held together without any gaps between the fingers. It is used to portray the action of blessing, to depict the air, sky, or water, to beckon another by waving the hand, to represent a plate, to indicate a stop, or to slap.

Fig. 2: Tripataka - Beginning with pataka, the ring finger is then bent. The other fingers should be straight and upright. It is used to depict the king and anything royal (like the crown), to show a bindi or tilak, or to draw a line.

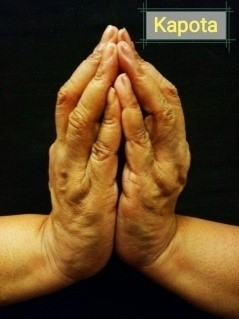

Following are images of some samyukta mudras:

Fig. 3: Shankha - Conch

Fig. 4: Kapota

According to Subhankara Kavi, who wrote Hastamuktabali, there is a distinction between ‘mudra’ and ‘hastakarama’ (Bela 1992:35–36). Mudra belongs to the tantras and tantric sculptures, while hastakarama belongs to the art of dance and drama. In Assam, the Vaishnavashastra circles use the Assamese word hat (hasta) in place of ‘mudra’. However, those who belong to the tantric tradition, like the Oja-Pali school of dance, regard the gesture as mudra. This community performs a dance representing the serpent goddess Manasa, and the worship of the eight-armed, white-complexioned Vishnu. Thus, there are three classes of hand gestures or mudras—Vedic, tantric, and histrionic.

According to Buddhist ritual, there are a number of tantric, ritualistic mudras associated with mystic formulae. They represent such holy objects as pasa, pushpa (flower), ankusa (elephant god), naivedya (offering), and dhup (incense sticks), and were used during tantric rituals. They include netra (eye), musti, pushpa, ghanta (bell), vajra (thunderbolt), naraca (iron arrow), tritattva (the three reels), and svikarana (acceptance).

The Sakta tantric text, Kalikapurana, written at Kamarupa in the 11th or 12th century AD, mentions 108 mudras—dhenu (cow), samputa (bowl), pranjali (joint palms), bilva (wood apple), padmaka (lotus), naraca, munda (head), danda (stick), yoni (female organ), vandani (supplicating), mahamudra (great mudra), mahayoni (great or holy yoni), bhaga (female organ), putaka (funnel-like leaf bag), nisanga (variant: nihsanga or accompaniment), ardhachandraka (half-moon), anga (limb), dvimukha (the two-faced), sankha (conch), musti, vajra (thunder-bolt), randhra (hole), satyoni (yoni), vimala (the pure), ghata (pitcher), sikharini (Goddess of Power), tunga (the elevated), urdhuapundra (upright mark on the forehead), sammilani (closing), kunda (pot-hole), chakra (discus), sula (javelin), simhamukha (lion’s mouth), gomukha (bull’s mouth), pronnama (the high-rising), unnamana (getting up), bimba (disc, orb), pashupata (Shiva’s bow), Suddha (the pure), tyaga (sacrifice), sarini (the moving), prasarini (the extending), ugra (the terrible), kundaliyyatha (spiral formation), trimukha (three-mouthed), asiualli (sword’s blade), yoga bheda (cleaving), mohana (the enchanting), vana (arrow), dhanu (bow), and tunira (quiver) (Neog 1991).

According to tantra, Brahma has especially praised these 108 mudras; rituals like japa (holy counting), pranayama, worship of god, yoga, dhyana (meditation), and asanas are fruitless without mudras. Among these mudras, only pranjali, padmaka, ardhachandraka, and musti are familiar as names of hastas (mudras) in histrionics, but other names from the list might also appear in the course of the viniyoga (application) of other hastas. It would perhaps be interesting to know the forms of these mudras.

Let us define the four mudras: pranjali, padmaka, ardhachandraka, and musti (Kalikapurana 1909). When the palms of the two hands are joined to make the shape of a trough (droni), and held as a cavity, the mudra is called pranjali. When the karabha (edges) of the two hands, beginning from the manibandha (wrist), the two thumbs, and the two little fingers are brought together, while keeping the other three fingers of each hand extended and free from each other, it is known as padma mudra, which can yield the fruits of the quadruple varga—dharma or piety, artha or material wealth, kama or desires, and moksha or liberation. The mudra formed by slightly bending the little finger, ring finger, and middle finger of the right hand and by extending the tarjani (forefinger) and the thumb of the same hand, as in ardhachandra, can propitiate the graha (planets).

Musti or mustika is one of the nine varieties of anga mudras. It is produced by keeping the thumb of the right hand upright and enclosing it in the fist of the left hand, whose thumb is also kept upright. In this mudra, if the fingers are released one at a time beginning with the little finger, eight different mudras are produced. Their names are dvimukha, musti, vajra, abaddha (bound), vimala, ghata (small pot), tunga, and pundra (king Pundra). With anga, the number becomes nine, which is associated with the nine mudras of Vishnu icons and their nayikas (heroines).

In Nritya, anjali is the placing together of two pataka hands (straight, with the fingers and thumb close together) on the sides, according to the Hastamuktavali. In the Natyashastra, the placing is not confined to the sides—the Abhinavabharati commentary is very clear on this point. Additionally, the Sangitaratnakara and the Abhinaya Darpana corroborate this point. However, the Kalikapurana mudra pranjali needs to be distinguished from the nrityaanjali (offering through dance).

There are two forms of ardhachandra in nritya. In one form, the four fingers are bent; the thumb is also bent separately, making the shape of a bow. This definition is similar in the Natyashastra and the Hastamuktavali, while the Abhinaya Darpana and Sangitaratnakara do not require a bending of the fingers or the thumb. According to the Hastamuktavali, the middle, ring, and little fingers are closed into a fist; the forefinger and thumb are separated slightly. This hasta is called chandrakala in the Abhinaya Darpana.

Musti is an asamyukta hasta mudra formed by closing the fingers into a fist with the thumb pressing on them. Its description remains the same in the Natyashastra and the Hastamuktavali, while in the Abhinaya Darpana, the thumb is placed only upon the middle finger. Nritya involves the use of the single-handed padmakosa, with all the fingers and the thumb separated and bent towards the palm, and the alapadma or alapallava (bloomed flower) with the digits looser than in padmakosa.

From a comparison, it is evident that the hastas and mudras have two clear lines of development—while the former are simple and objective gesticulations, the latter follow an intricate pattern, signifying the esoteric character of the rituals in which they are employed.

The application of mudras to invoke emotions, nature and reality is not limited to dance. In fact, mudras cross the boundary of dance and enter the world of abhinaya (acting), where they perform crucial symbolic, interpretative and poetic functions. At this point we may turn to the aesthete Ananda Coomaraswamy, who has shown how the symbolic turns pictorial on the dramatic stage. He writes, ‘Let us take a few episodes from the “Sakuntala” of Kalidasa and see how they are presented. The watering of a tree is to be acted according to the following direction. First show Nalini-Padmakosa hands and palms downward, then raise them to the shoulder, incline the head, somewhat bending the slender body, and pour out. Nalini-Padmakosa hands are as follows. Sakuntala’s hands are crossed palms down, but not touching, twined a little backward, and made padmakosa (Chottopadhaya 2008:64).' This account indicates that, following the rules of Bharata Muni’s Natyashastra, mudras—both samyukta and asamyukta—travel fluently and ceaselessly from one creative form to another. In other words, mudras play an overarching role, straddling drama and dance.

It is, therefore, not surprising that this unique form of communication finds mention in other texts, both religious and aesthetic. In the third section of Narada Pancharatra, we come across 24 different mudras, which are mentioned in Vedic and post-Vedic literature. They are even invoked to elaborate on Panini’s teaching.

As Bajsaneyo Pratisakhya, a worthy commentator, has said, ‘Going back to the Vedic times however, one finds the word and the gesture on one plane, and it is given the same magical or religious importance’ (cited in Chottopadhyay 2008:59–60). Mudras are also closely related to tantric practices prevalent in Hinduism and Buddhism. Western critic Dr Jean Przyluski has also dwelt on this relationship: ‘The study of the word Mudra, in fact, shows the pre-eminence of the tendencies which have ruled the first manifestation of Buddhist art, and through it the political economic and religious life of India may be linked together (cited in Chottopadhyay 2008:59–60).' Five examples and interpretations of Buddhist mudras are offered below to illustrate the creative process.

Fig. 5: Abhay (fearlessness): The abhay mudra is made with the open palm of the right hand extending outwards at chest level or slightly higher. It is performed to show fearlessness.

Fig. 6: Karana (powerful energy): This is made by raising the index and little fingers and folding the other fingers. The thumb does not touch the middle and ring fingers. This mudra is performed to expel negative energy and remove obstacles such as sickness or negative thoughts.

Fig. 7: Vajra mudra: This mudra is formed by enclosing the erect thumb of the left hand in the right fist with the tip of the right forefinger circling around the tip of the left forefinger. This is known as the six elements mudra and symbolises the unity of the five worldly elements—earth, water, fire and air—with spiritual consciousness.

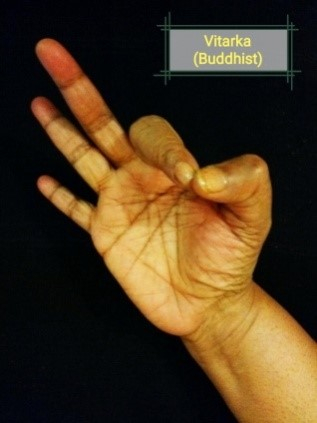

Fig. 8: Vitarka (teaching transmission): This mudra is made by touching the tips of the thumb and the index finger to form a circle, which represents the wheel of law. The middle, ring and little fingers point upwards. This is a mudra of discussion, intellectual argument, and transmission of Buddhist teaching.

Fig. 9: Dharmachakra (cosmic order): The hands are placed at the heart level, with the thumbs and index fingers forming circles in a manner similar to vitarka mudra. The right palm faces outwards and the left faces the heart. This mudra expresses the continuous energy of the cosmic order and is symbolised by a wheel or chakra.

We need not confine ourselves to the past. Mudra, gesture or geste (as it is called in German) has crossed centuries and continents to inspire the plays of German dramatist Bertolt Brecht. In a succinct interview, noted poet and Brecht expert Alokeranjan Dasgupta said to me, ‘Brecht’s epic theatre is based on gestures and expressive movements. There is no doubt that he imbibed the praxis of gestures from Oriental aesthetic, the Mudra-system in particular.’ When one reads or witnesses a Brechtian production, one is struck by the similarity between gestural work in his plays and in Indian dance histories. Like dance artists who create their own worlds of Kathak or Bharatanatyam with mudras, Brecht’s characters also convey emotions with the help of objective gestures, in order to focus on a separate, alienated world. Mudras, then, have come a long way from the ancient world of Indian classical dances to the revolutionary world of Brecht’s theatre.

We can now pose a rhetorical question: Is mudra an integral part of dance, or is dance an integral part of mudra? The answer is that both are interdependent and equally important. However, mudra crosses the limits of dance and establishes a creative relationship with abhinaya. Mudra, therefore, enjoys an overarching significance, while dance, within its self-regulated boundaries, encourages mudra to be deep and pervasive. The famous critic and theorist Curt Sachs (n.d.:58) places dance above all other expressive art forms and mudra contributes to its elevated singularity. In other words, if mudra is the language of dance, then dance, considered the ‘mother of art forms’, comes to depend on mudra for its intense and variegated expressiveness. Thus, a dialectical relationship blooms between dance and mudra, and the desired synthesis is attained by the exquisite combination of both.

In his book World History of Dance, Curt Sachs explains why he considers dance to be the mother of all arts. He writes, ‘Dance is the mother of all arts. Music and poetry exist in time; painting and architecture in space. The creator and the thing created, the artiste and the work are still one and the same thing. Rhythmical patterns of movement, the plastic sense of space, the vivid representation of a world seen and imagined – these things man creates in his own body in the dance before he uses substance and stone and word to give expression to his inner experience’ (cited in Chottopadhaya 2008:58). What must be noted at this juncture is that the autonomous associate—the mudra—enters the body of the dancer and the dance form and creates a compelling movement, which encases the rhythmic body and the demonstrative mudra. This is a simultaneous process of togetherness, which demonstrates that the confluence cannot be separated.

The epistemological aspect of mudra lies in the fact that this confluence leaves its traces in the socio-economic world as well. In this developed sense, mudra becomes a part of the social, human world. Dr Jean Przyluski emphasises, ‘The study of the word, Mudra, in fact, shows the permanence of tendencies which have ruled the first manifestations of Buddhist art, and through it the political and economic and religious life of India may be linked together’ (cited in Chottopadhaya 2008:60). Its entrance into the tantric world of Buddhism and Hinduism deserves a special mention. Elaborating on this intimate connection between religion and mudra, Ananda Coomaraswamy has observed, ‘The symbolism of gesture includes the various positions of the hand known as mudras; of physical peculiarities – the third eye of the Shiva or the elephant head of Ganesha are appropriate instances’ (cited in Chottopadhaya 2008:60).

This paper emphasises three different aspects of mudra and their applications. These are:

1. The history of mudra, highlighting the relationship between dance and mudra.

2. The importance of mudra in the tantric sphere of art and worship; and

3. The pervasive influence of mudra on Buddhism.

Note: The photographs of the mudras included in the text were clicked by Steve Albert Michael and performed by Surangama Lala Dasgupta.

References

Acharya, Krishna. 1990. Nritya Darpan. Kolkata: Ratna Devi.

Adhikary, Arup Shankar. 1973. Nritya Bitan. Kolkata: Sangit Prakashan.

Arnab, Bela. 1992. Kathak, Swarup O Bibartan. Kolkata: Pandulipi.

Bandyopadhyay, Nilratan. 1972. Hindusthani Nrityasaili Kathak. Kolkata: Sangit Prakashan.

Bharata Muni. 1980, 1982, 1982, 1995. Bharat Natya Shastra Volume 2, trans. Sureshchandra Bandyopadhyay and Chanda Chakravarti. Kolkata: Nabapatra Prakashan.

Chatterjee, Gayatri. 1985. Bharater Nrityakala. Kolkata: Karuna Prakashani.

Deshpande, G.T. 1975. Nandikesvara’s Abhinaya Darpana – A Manual of Gesture and Posture used in Ancient Indian Dance and Drama. Kolkata: Satya Bhattacharjee for Manisha Granthalaya.

Devi, Ragini. 2002. Dance Dialects of India. Delhi: Motilal Banrasidass.

Markandeya, Maharshi. 1909. Kalikapurana, A Compilation, edited nu Avharya Panchanan Tarkaratna. Kolkata: Naba Bharat Publishers.

Mansingh, Sonal. 2007. Incredible India Classical Dances. New Delhi: Wisdom Tree.

Neog, Maheshwar. 1999. Srihastamuktabali. In Kalamulsastra Series (3), edited by Kapila Vatsyayan. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts in association with Motilal Banarasidass.

Tarlekar, G.H. 1999. Studies in the Natyashastra. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass.