Although closely associated with principles of asceticism and renunciation, Jainism, for the last two millennia, has been a religion of temples and temple worship. Jain temples, with the diverse ritual implements of sculpted and adorned jina (enlightened and liberated teachers) images, monastic robes, meditational aids, books, manuscripts and a myriad other objects, have created a rich material culture that has dispensed specific ritualistic functions of interaction between Jain monks and the laity. (Fig. 1)

Major duties of worship (deva puja) in the life of a Jain murtipujak (idol worshipper) comprise dedication of jina images, donation of sacred books, building temple libraries and constructing temples. Jnan (salvific knowledge) plays a crucial role in Jain philosophy, and the worship of books of wisdom (jnan puja) is a central activity in the Jain temple ritual. Eminent Jain scholar John E. Cort points out that according to the Jain cosmological doctrines, in the absence of any living enlightened teacher after the liberation of Mahavira over 2,500 years ago, the texts containing the teachings of Mahavira are essential for the guidance of the Jain community.[1] Hence, written copies of manuscripts and books in Jainism are material objects that have taken on a ritual and symbolic life of their own. From as early as the sixth century, a growing concern about preserving the faith’s written authority as well as this Jain tradition of textual knowledge led to the building of bhandars (monastic libraries) that formed an integral part of temple complexes.[2] Great depositories of Jain textual knowledge, these temple bhandars in places like Jaisalmer and Patan actually contributed as the most invaluable source of reconstruction of the history of Jain religion, its social institutions, philosophy and art.

Nestled in the small hamlet of Azimganj, approximately an hour’s journey from Murshidabad on the far side of the Bhagirathi River, are a cluster of seven Jain temples. Shri Shri Neminathji Maharaj Temple, established in 1887, is the central ‘panchayati’ temple today, around which the other Jain temples in Azimganj are located. Under the trusteeship of and maintained by Azimganj Jain Svetambar Sangh, this temple is dedicated to the 22nd tirthankar, Neminathji. As early as the eighteenth century, prosperous Svetambara Jain merchants, traders and financers settled in the Murshidabad–Azimganj–Jiaganj area fulfilled their religious obligation of charity and public service to the temples by donating and dedicating sacred texts of handwritten manuscripts and books creating a depository of the temple bhandar that still exists, currently concentrated in only one of the 14 temples of the area. What we find today in the Shri Neminathji Bhandar temple of Azimganj is probably a remnant of a vast collection that is damaged, lost, dispersed or stolen over time, making it imperative to document and record what exists of this invaluable piece of history.

As the Jain monks were peripatetic and the temples repositories of the faith’s knowledge system, the temple libraries played a crucial role for the Jain laity to improve both their worldly and spiritual lot by managing, donating, dedicating and collecting books for the jnan bhandar. The temple libraries are run mostly by the congregation of laymen of the community. The management works at different levels—at city or neighbourhood levels or hereditarily managed by a single family.

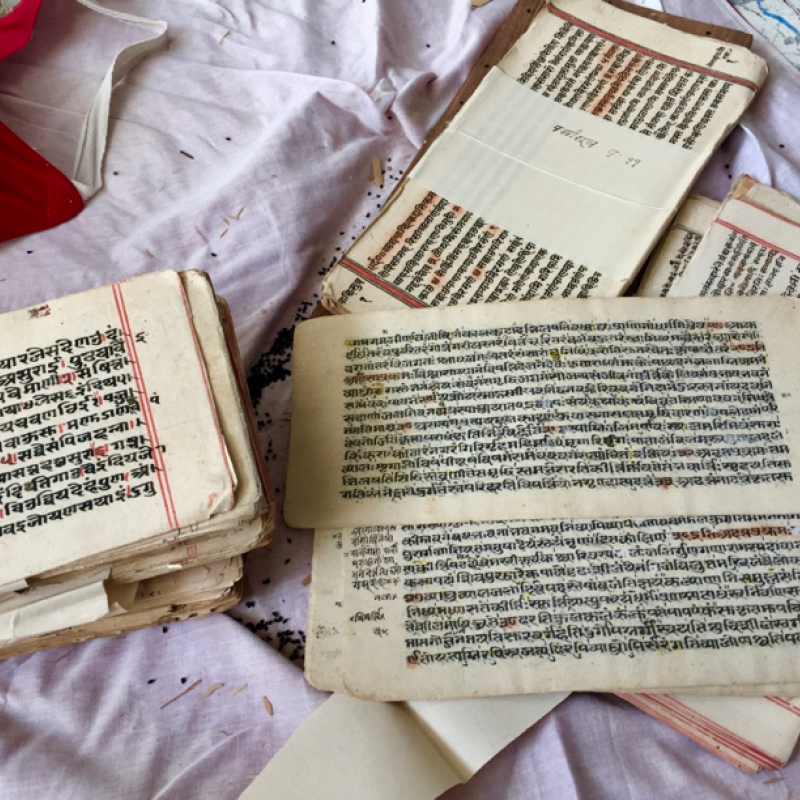

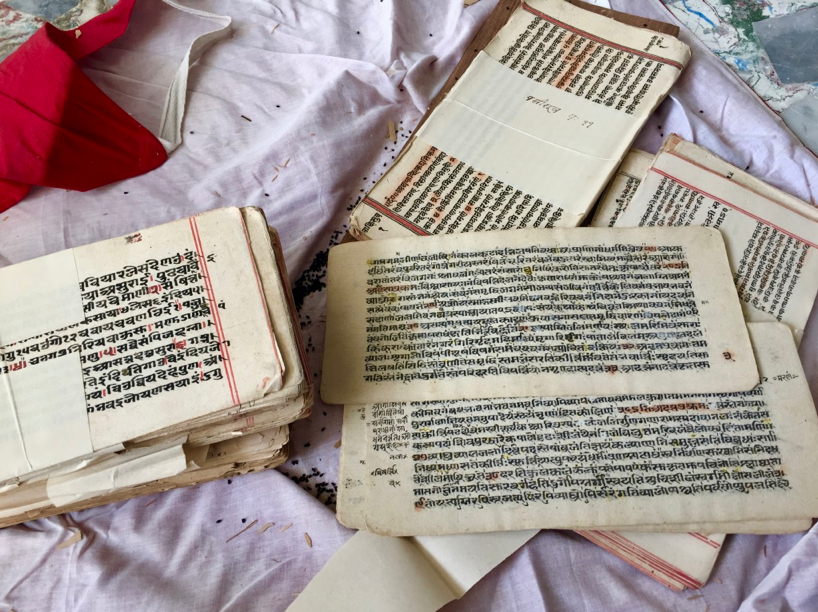

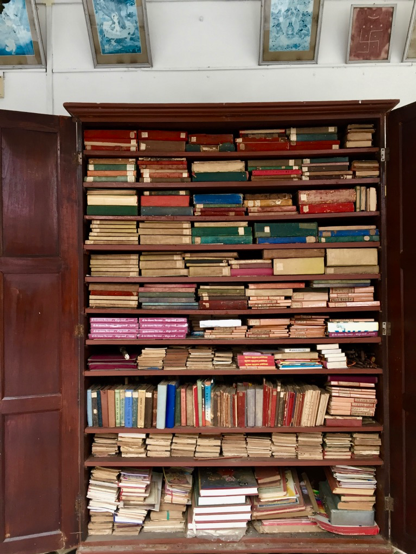

Azimganj Jain Svetambara Shree Sangh is the body entrusted with the management of the temple library collection that is today concentrated in a cupboard of Shri Neminathji Bhandar Temple of Azimganj. (Fig. 2) The sacred texts in this cupboard, recently organised thematically during the charmasa (monsoon stay of the Jain monk Sri Sashiprabhasriji), consists of both handwritten manuscripts as well as printed books.

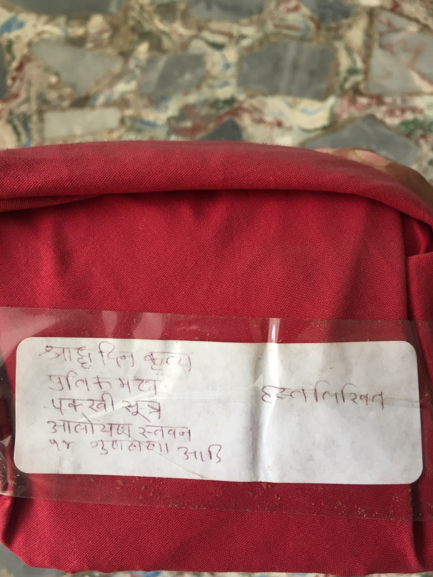

Established in the early modern period, roughly in the last quarter of the nineteenth century—unlike most of the traditional Jain jnan bhandars—Shri Neminathji Bhandar Temple complex and its library do not have any manuscripts on palm leaves. A perusal of the handwritten manuscripts on paper indicates that they date mainly between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and some of the titles have multiple copies. Since the manuscripts are a part of the religious complex as indicated by the worship of books of wisdom as a central activity of temple rituals, their arrangement and organisation evoke particular interest. The paper folios of the textual manuscripts, after being thematically arranged, are carefully placed between two patlis (wooden covers) which are then placed inside a red cloth and made into a bundle. Indigenous methods of paper preservation can be noted on opening the bundle—kalonji (nigella seeds), which is a natural absorbent of moisture, and dried red chilies, which keep away moths and bookworms, have been carefully placed in every bundle, ensuring the physical preservation of the manuscripts. (Fig. 3).

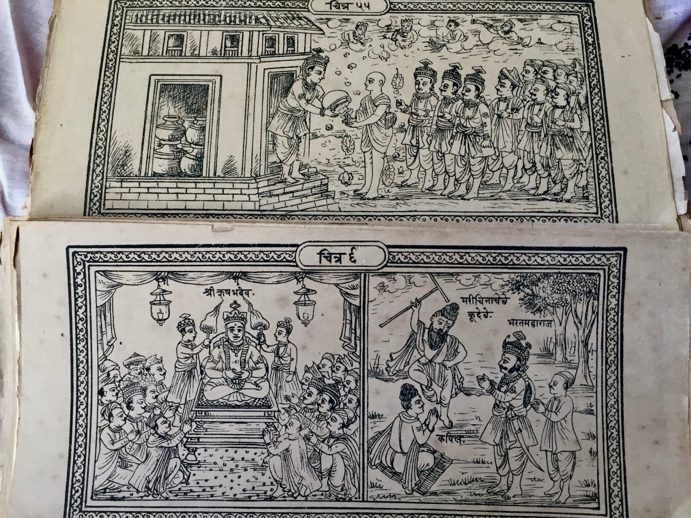

A preliminary investigation of some of these texts reveal the script to be either Prakrit or Sanskrit while the dialect in which they are written varies. Further inspection into the titles of the manuscripts reveal multiple copies of texts belonging to the Svetambara canon, devotional texts used in community rituals and narrative texts used by monks for basic sermons, while texts on complex Jain philosophy, cosmology and high theology are fewer in number. Not surprisingly, the maximum number of copies are made of the Kalpasutra manuscripts (the most frequently illustrated text of the Svetambara sect). The Kalpasutra deals with the lives of the jinas, especially of Mahavira, Parsva, Nemi and Rsabha. Some of the other important titles that deserves mention are the Jambudvipa Sutra, Navkar Bal Bodh, Dravya Gupt Paryay and Pakhi Sutra. (Fig. 4) As John E. Cort points out, the pragmatic choice of which manuscript to copy was directly related to the manuscript’s ritualistic usages for which the Kalpasutra manuscript remained oft copied while more technical and philosophical works were copied less frequently.[3]

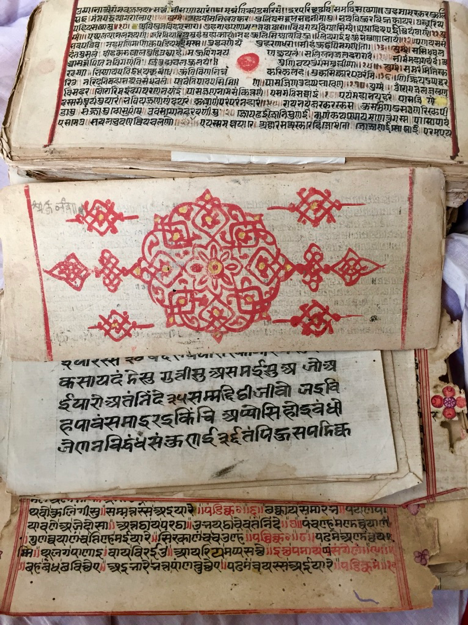

In most Jain temple libraries in west India, the wooden cover of the patli and the manuscripts are richly decorated and illustrated as both are considered highly portable objects of veneration. A rudimentary inspection of the manuscripts in the Azimganj temple collection did not result in finding either any decorated patli or any illustrated manuscript of historical value. The only example of visual aesthetics in the manuscripts that can be traced is confined to a few lightly decorated flyleaf pages, one of which is incomplete. (Figs 5 and 6) However, it is known that a few European library collections, like that of the British Library, houses Jain illustrated manuscripts whose provenance have been attributed to eighteenth-century Murshidabad in Bengal, confirming the testament of the Azimganj temple’s current manager who holds that decorated, painted and illustrated manuscripts of considerable value have got dispersed and cannot be located within this temple’s library collection. Whether they have made their way into Western libraries, museums and research institutes, have been transferred to contemporary depositaries of Jain manuscripts like Koba in Ahmedabad or remain with the Svetambara congregation and its trustees is yet to be charted out.

The advent of the printing press and publishing has transformed the nature of these traditional Jain temple libraries, as the requirement for multiple copies of handwritten manuscripts for ritual purpose have been replaced by printed versions. The published editions follow the earlier manuscripts in form and content as is evident in figure 7, which is a printed illustrated copy of Kalpasutra manuscript. Closer observation of the folio shows that it is regularly used in ritual purposes as against the handwritten manuscripts that have moved away from playing an active part in ritual traditions and remain locked up in an isolated cupboard of the temple. This, however, has led to the demise of the devotional practice among the Jain laity as for them copying manuscripts for religious merit has been replaced by donating published books of different ritual and educational purposes to the temple, bringing about a transformation in the nature of the dana (charity)-dharma itself. As is evident from figure 8, not just the books but the cupboard to keep the books has also been donated by an individual donor of the sangh (community of the pious), which fulfils the transformed nature of the dana and public service along with improving the donor’s worldly and spiritual merit by jnan puja.

The evolution in the nature of the dana-dharma has created a marked distance between the common laity and traditional jnan bhandar by which manuscripts have ceased to be an essential and everyday part in the Jain ritual traditions and remain in isolation, relegated to being of remote antiquarian value. In the absence of any cataloguing or proper documentation whatsoever, this immense repository of knowledge has failed to attract the scholarly and academic attention it demands. Therefore, placing this rich, valuable and unexplored traditional Jain temple library of Azimganj in the cultural and historical map of Bengal will hopefully open up the possibility of its further investigation and exploration before the manuscripts are lost forever.

Notes

[1] Cort, ‘The Jain Knowledge Warehouses,’ 77.

[2] Guy, ‘Jain Manuscript Painting,’ 92.

[3] Cort, ‘The Jain Knowledge Warehouses,’ 79.

Bibliography

Cort, John E. ‘The Jain Knowledge Warehouses: Traditional Libraries in India.’ The Journal of American Oriental Society 115, no. 1 (1995): 77–87.

———. ‘Art, Religion and Material Culture: Some Reflections on Method.’ Journal of the American Academy of Religion 64, no. 3 (1996): 613–32.

———. Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain history. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Johnson, David Clay. ‘The Western Discovery of Jain Temple Libraries.’ Libraries & Culture 28, no. 2 (1993): 189–203.

Guy, John. ‘Jain Manuscript Painting.’ In The Peaceful Liberator: Jain Art from India, edited by Pratapaditya Pal. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994.