The emergence of the Jain community in the Murshidabad area of Bengal was the result of two distinct waves of migration. Between 1700 and 1765, the dominant Jain actors were the Jagat Seths (banker of the world), a line of merchant-bankers who had migrated to this region from Marwar in Rajasthan. They trace their ancestry to Hiranand Gailara, member of one of the most illustrious Oswal Jain families of the Gailara gotra.

Hiranand Gailara migrated from Nagaur (in Marwar)[1] to Patna in the sixteenth century and became a successful banker and saltpetre merchant.[2] One of his six sons, Manikchand, who moved from Patna to Dacca, played a principle role in advocating the transfer of the capital of Bengal from Dacca to the town of Maksudabad on the east bank of the river Bhagirathi.

Under the new nawab of Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan, the new capital was renamed Murshidabad, and it saw the appointment of Manikchand as the deputy diwan tasked with the organisation and supervision of revenue collection and management of the treasury of Bengal. Manikchand was also the personal banker to the nawab, with whom he is jointly credited to having invested heavily for the development of Murshidabad and its surrounding environs. Functioning in a cash-strapped economy, Manikchand’s banking network functioned seamlessly to facilitate the Mughal emperor in Delhi, the Bengal nawab, the English East India Company and other high-level imperial aristocrats and bureaucrats to whom he operated as a personal financier. His services earned him the title of Jagat Seth; this family title was reconferred upon every head of the family succeeding Manikchand by the later Mughal emperors and the Bengal nawabs until the British abolished the nawab’s position in the late nineteenth century.[3]

Wielding considerable political power in Bengal because of their combined responsibilities of revenue collection and financing the nawab and the Mughal emperor made the Jagat Seths important players in the turbulent political landscape of eighteenth-century Bengal. Management of revenue administration required a considerable workforce and the Jain community ethos saw the Jagat Seths recruiting trusted agents from the Jain community operating in key positions, both locally and elsewhere in Bengal and beyond. This led to a steady influx of the Jains from western India and Rajasthan to Bengal, marking the second wave of Jain migration in the province.

The period after 1765 saw a rise in the influx of Rajput Kshatriya Jains, who initially followed the footsteps of the Jagat Seths and eventually formed banking and financial setups independent of them. They came to be known as the Sheherwali (urban) Jain community of Murshidabad, and quickly went on to become zamindars in Azimganj and Jiaganj, areas adjoining Murshidabad. During the nineteenth century, with a steady decline in status of the Jagat Seths, the Sheherwali Jain community went on to become icons of wealth and pomp in Murshidabad, playing a prominent role in the political, economic, social, cultural and religious life of the area ever since.

Even though not homogenous in character, the Jains of early modern Bengal (seventeenth to nineteenth century) had one thing in common—a strong sense of community, harnessed on religious lines, which got particularly amplified because of Murshidabad’s proximity to Mount Pareshnath, one of the principle Jain pilgrimage sites which is believed to have been the place where 20 of the 24 Jain tirthankaras (ford makers) had attained moksha.

Being staunch practising Svetambara (literally, white-clad) Jains, the Jagat Seths acted as true leaders of the Jain community in early modern Bengal and not only initiated construction of Jain temples in and around Murshidabad but also contributed to the religious welfare of the community by obtaining revenue-free lands surrounding Mount Pareshnath from the Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah.[4] The extensive temple-building in Murshidabad and Pareshnath, organised pilgrimages led by the Jagat Seths, their lavish religious donations and patronage set a standard of religious service that was respected and eventually emulated by the Sheherwali Jains, thereby establishing a strong Jain presence in the religious landscape of early modern Murshidabad.

Tracing its roots back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the areas of Azimganj–Jiaganj–Murshidabad today forms a cluster of 13 active Jain Svetambara temples, which by Jain religious standards entitles the location of the temples to be called a tirtha (pilgrimage site). It is around these tirthas that a lesser-known Jain visual culture developed, influencing the evolution of Jain identity in the last 250 years in the province of Bengal.

Jain Visual Culture in Bengal

Jainism has, for two millennia, been a religion of temples and temple worshippers. At the centre of the Jain culture of temples and images are the jinas (enlightened and liberated teachers). The word jaina (from which comes Jain) is derived from Sanskrit jina (conqueror). According to Jain theology, each jina has attained the state of a pure soul, devoid of all karmic bondages, and marked by the four infinitudes of perception, knowledge, potential and bliss. It is also a state that is completely devoid of contact with the material world, as the liberated soul resides in the highest realm of the cosmos.[5] The temples thus are regarded as elaborate and ornate configurations of samavasarana (celestial assembly halls) of the jinas. Thus, in the arts of the Jain temple architecture, sculpture, paintings and the material objects, aesthetic values have generally been subordinate to religious ones, whose main function has been to communicate core religious values largely designed to serve ritual functions.

The prosperous mercantile-banking Jain community of the Murshidabad area as a major duty of their devapuja (worship of the jina) took up extensive temple-building projects not only to fulfil the obligation of charity and public service but also to satisfy the individual’s need for achieving the proper mental attitude for spiritual guidance. The Murshidabad Jain Tirtha thus, today, claims a conglomerate of a dozen active Jain temples forming a triangle between the towns of Azimganj (seven temples), Jiaganj (three temples), with its apex at the Kathgola Nashipur and Mahimapur temples in the town of Murshidabad.

Visualising the Jina Icons

The Shri Shri Neminathji Maharaj Temple established in 1887 is the central panchayati temple today around which the other Jain temples in Azimganj are located. Under the trusteeship of and maintained by the Azimganj Jain Svetambara Sangh this temple is dedicated to the 22nd tirthankara Neminathji.

The principal deity of Shri Neminathji, made of marble gilded with silver and gold plates, is placed on an illustrated pedestal. (Fig. 1) The central figure of the Neminathji appears between the figures of Krishna and Balarama, considered his cousins. This conforms to the traditional iconography of Neminathji which shows a mutuality between the Brahminical and Jain pantheon. Through the depiction of the jina images there is constant effort at upholding an aesthetics of symmetry in Jainism, which further conveys the stability and perfection of the Jain cosmos.

The Jain pantheon comprises numerous yaksha-yakshis (benevolent, sometimes capricious nature spirits), upadevatas (minor deities) and divinities such as Saraswati, Lakshmi and Ganesha in addition to the 24 tirthankaras. This temple too is lined with numerous shrines of different jinas such as Adinathji, Neminathji and Parsvanath.

The chaumukhi (four-faced) jina icons (Fig. 2) signify the auspiciousness of the jina icon on all sides. While the jinas retain their primacy in ritual practice and devotion, modelled on these are later shrines dedicated to Jain acharyas (Fig. 3)—monks, miracle workers, reformers and creators of new Jains—conceptualised in the form of meditating ascetics to be venerated and worshipped. The dvitirthi, tritirthi or chaumukhi Jina images that represent two, three or four different jinas together have played a significant role in exploring the dynamic tension between singularity and multiplicity, and between monotheism and polytheism inherent in Jainism.[6]

While the highest ideal in Jainism is asceticism, the jinas were also modelled on kings, which showed characteristics of ascetics as well as of kings. Drawing on the kingly kshatriya origin of the tirthankaras, the concept of the tirthankaras as models of human victory over the attachments and aversions of the soul’s bondage upheld them as spiritual victors, i.e, jinas.[7] The visual imagery of the tirthankaras embedded in this philosophy thus rendered the icon of the jina in either of these two models. (Figs 4 and 5)

The jina altarpieces in the Sawonliya Pareshnath temple in the Rambagh area of Azimganj is the most suitable example of this dual characteristic; Figure 4, depicting an altarpiece of jina chaturvimshatika or jina chauvisi, represents 24 jinas carved together. The Parsvanatha icon on the top of the octagonal step is the mulanayaka (main idol), while the figures of the other 23 jinas are depicted in the parikara (surrounded) manner in diminutive forms. Carved out of simple marble, this unadorned altarpiece highlights the renunciatory and ascetic aesthetics associated with the faith. Figure 5, however, depicts the jina figures made on marble, enthroned and adorned in a regal manner. With parasols above their head and a halo behind, the kingly divinity of the icons is enhanced with jewellery.

Figure 6, a photograph of a display cabinet of the Sambhavnath Bhagwan Temple in Jiaganj, represents with its seemingly identical dozens of jina icons from the eighteenth to the twenty-first century, a sense of the Jain understanding and representation of a cosmos, filled with perfect and undifferentiated jina images.

Jain Temples of Murshidabad Tirtha: A Brief Architectural Survey

The first and second waves of Jain migration in Bengal saw a transmission of architectural form, mode and style carried forward from the classical temple-building traditions of early medieval Rajputana. Jain temples displayed the architectural format of flat-roof temples—distinct from the regional temple architectural style concurrent in Bengal—with shikharas (articulated curved spires). Although the Jain temples of Murshidabad date back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, their present structures are the result of vigorous renovation works continually undertaken by devotees as prosperous Jains, familially and congregationally, continue to renovate old temples. The Chintamani Parsvanatha Temple in Azimganj is the oldest existing temple structure among the conglomerate of these Jain temples, dating back to the late nineteenth century. (Fig. 7)

The temple has a simple layout, with an inner sanctum, ambulatory and mandapa (colonnaded hall) overlooking a courtyard. (Fig. 8) The architectural features of the articulate and lofty shikharas adorning the roof of the mulaprasada (main shrine), the cusped arches of the colonnaded veranda, and the kalasha (pitcher)-shaped angashikharas are western Indian temple features transmitted to Bengal that make Jain temples distinguishable from other Hindu temples.

A regional peculiarity of these Jain temples of Bengal is observed in the materials used in construction. While either stone or marble was used in construction in western India, the absence of both these in early modern Bengal resulted in the use of locally available lime and mortar. The exterior was adorned with decorative elements like haveli-style windows or motifs resembling lattice screens (Fig. 9), which stylistically brings them closer to the western Indian Jain temples of Gujarat and Rajasthan, albeit much simpler in decoration and scale.

Instead of the intricately carved marble interiors associated with the typical western Jain temples such as Ranakpur Temple or Dilwara Temple in Mt Abu, the temples in Bengal just use marble in the flooring and marble plaques are sometimes installed on the walls for decorative purposes—which have in recent times after renovation been coloured golden to give them a more embellished look. (Fig. 10) The closest resemblance to the ornamental richly carved marble interiors of the western Jain temples can be witnessed in the replication of similar motifs and designs with stucco work called pankha in some of the larger Jain temples such as the Adinathji Bhagwan Temple of Kathgola Palace. (Fig. 11) Superior artisanal skill in stucco work has been a feature of Murshidabadi architecture since the Nizamat period which was carried over well into the twentieth century in these Jain temples as well.

Older temples, done on a limited budget, extensively used tiles found in abundance in the area for the interior decoration. The interesting observation here, however, is that the majority of the tiles are Delftware tiles, of Dutch origin, used extensively in several Jain temples in Azimganj-Jiaganj. (Fig. 12) Murshidabad displayed an interesting rubric of cultures due to the prolonged mercantile presence of different European companies in the medieval and early modern period, and this had its particular influence on Jain temples as well.

The most enduring legacy of the Jains that still has a distinctive physical footprint in the architectural development of the temples of this region can be observed in the continuous renovation work (Fig. 13) undertaken by the sangh (congregation), which in turn reaffirms the social and cultural self-image that the Jains want to project as a social and religious community wielding considerable importance in this part of the region.

In Jainism, the temple is a symbol of the universe conceived in the form of the param purusha/vastu purusha (cosmic man). Paying attention to the architectural details and the regional peculiarities of the Jain temples of the Murshidabad Tirtha thus gives us an interesting insight into the constantly evolving Jain visual culture that was adapted and adopted in Bengal around the temple of the jina.

Situating the Jina in the Visual Culture of the Jain Temples

The ritualistic requirements of the veneration of the jina images created a full material culture of books, monastic robes and illustrated manuscripts while the temples have incense, jars, garlands, bells, banners, umbrellas, etc., to aid in meditation and veneration. An overview of the visual and material culture in these temples indicates the underlying fundamentally materialistic aspect of Jainism, which also explains the identity formation of the emigre Jains as a mercantile community tracing their roots to medieval Rajputana.

Amidst the many ritual objects, old and new, is the architectural remnant of what can be understood as a section of an archway. (Fig. 14)

Lying beside a home shrine of an old Jain family, this intricately carved torana (archway) once formed a part of a gateway. The carved panels do not indicate a strictly Jain subject matter—a variety of human, animal and mythical figures are depicted converging towards the top of the archway to venerate or worship. In the absence of knowledge of the place or time of its origin, this archway stands as a witness to the highly expressive devotional intensity associated with Jainism and its ritual and visual culture. The ayagapatas (copper votive tablets) in square, rectangular or circular format typically decorated with etched images of the jinas, the Jain cosmos and mandalas that represent different auspicious symbols to suggest the prevalence of symbol worship in Jainism in the Shri Shambhavnath Temple in Jiaganj, provide insight into the devout patrons of the faith. (Fig. 15) The inscriptions on the tablets reveal details of the donor that help chart a pattern of patronage of the temples, along with the construction, reconstruction and renovation work taken up as a form of deva puja.

The narrative of these jina icons, understood to be eternal, is found in Jain cosmology, which has been the central subject matter of a great corpus of canonical Jain treatises that have also found visual representation in a dense repository of illustrations. With the vision of a universe extending indefinitely in both space and time, Jain authors from ancient times lavished great efforts in providing details of this eternal, infinite universe that found expression in exquisite painted descriptions of illustrated cosmological manuscripts and detailed illustrated diagrams.[8]

The representation of the world that the Jains elaborate in the visual culture conceptualised around the temple permits them to show in a condensed way the myriads of destinies through which one will transmigrate in the course of the eternity.[9] Dominated by circles, which have always been abundantly used in Jain illustrations, the complex and essentially symmetrical composition deployed to construct the Jain cosmos gives it the architecture of a mandala—useful for depicting in an abstract form the ultimate order of the cosmos.[10] The centre of a yantra (mystical diagram) at Shri Neminathji Temple, Azimganj, depicts the jinas, and the circle immediately surrounding the icons also represents four Svetambara monks. (Fig. 16) An artistic elegance and simplicity is evident in the lines, and the harmonious colour balances have not been disturbed even with the saturated intensity of colour application and minute writings on the painting.

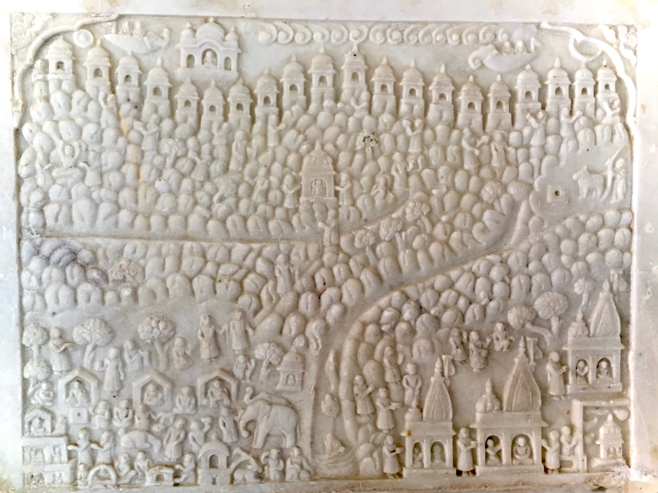

Beginning as a rite of commemoration, pilgrimage to the tirthas has evolved as a celebration of the extraordinary tirthankaras, who attained perfect knowledge and liberation from the cycle of rebirth. Shared by the monastic community and laity, pilgrimages became a Jain ritual to evoke piety and devotion. Many pilgrimage pictures of the different sites such as Girnar, Palitana, Abu and Satrunjaya have also been illustrated through the ages, and stand as representation of sites for devotees who cannot undertake the physical journey. Installation of such marble panels (Fig. 17) in the temples of the Murshidabad Tirtha thus gives currency to the idea of making further pilgrimages to the depicted sites as well as mentally being transposed to the represented tirthas in the event of physical inability to do so. The pilgrimage paintings or panels bring to the site the benefit of all other holy sites and illustrate the words of praise that we find repeated in medieval texts: to worship here is to gain the merits of worshipping everywhere else.[11]

The area encapsulates a glorious history of not just a community and its religion but of a culture that has remained largely unrepresented and uncharted in the visual landscape of Bengal. The temples—along with the Jina icons, votive tablets, marble plaques and even the temple architecture—were intended primarily to disseminate core religious values and serve a ritual function more than meeting aesthetic standards. The Jain sites of Azimganj–Jiaganj–Murshidabad today are either visited by travellers who spend the weekend in Murshidabad or by devout pilgrims whose usual itinerary is to spend a day at the Azimganj–Jiaganj temples and half a day at the Mahimapur–Kathgola temples.

In Bengal, thus, the experience of Jain migration is as much a compelling story of the new socioeconomic and political arrangement as it is of the emergence and evolution of a religio-aesthetic development which set in motion, in the eighteenth century, continues to thrive and evolve.

Over the last decade or so, some of the influential Sheherwali families, such as the Duggars and the Nowlakhas, have tried to renew interest in these sites by developing a body called the Murshidabad Heritage Development Society through which they try to popularise not only the nawabi remnants in Murshidabad but the rich Jain culture and heritage that survived continuously from the early modern period.

Much remains to be explored and documented about the Jain presence in Bengal and, for all that we know, it is a treasure trove waiting to be discovered.

Notes

[1] Bhandari, Oswal Jaati ki Itihas.

[2] Doogar, ‘From Merchant-banking to Zamindari,’ 28.

[3] Ibid., 28.

[4] Ibid., 32–33.

[5] Cort, ‘Following the Jina, worshipping the Jina,’ 39.

[6] Cort, Framing the Jina, 74.

[7] Babb. ‘Monks and Miracles.’

[8] Caillat and Kumar, Jain Cosmology, 34.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 74.

[11] Granoff, ‘Jain Pilgrimage,’ 69–70.

Bibliography

Babb, L.A. ‘Monks and Miracles: Religious Symbols and Images of Origin among Osval Jains.’ The Journal of Asian Studies 52, no. 1 (Feb 1993): 3-21.

Bhandari, S.R., et al. Oswal Jati ka Itihas. Indore: Oswal History Publishing House, 1934.

Caillat, Collette, and Ravi Kumar. Jain Cosmology. New Delhi: Bookwise, 2004.

Cort, John E. ‘Following the Jina, worshipping the Jina: An essay on Jain rituals.’ In The Peaceful Liberator: Jain Art from India, edited by Pratapaditya Pal. London: Thames and Hudson and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1994.

———. Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Doogar, Rajib. ‘From Merchant-banking to Zamindari: Jains in 18th and 19th Century Murshidabad.’ In Murshidabad Forgotten Capital of Bengal, edited by Neeta Das and Rosie Llewellyn-Jones. Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2013.

Granoff, Phyllis. ‘Jain Pilgrimage: In Memory and Celebration of the Jinas.’ In The Peaceful Liberator: Jain Art from India, edited by Pratapaditya Pal. London: Thames and Hudson and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1994.