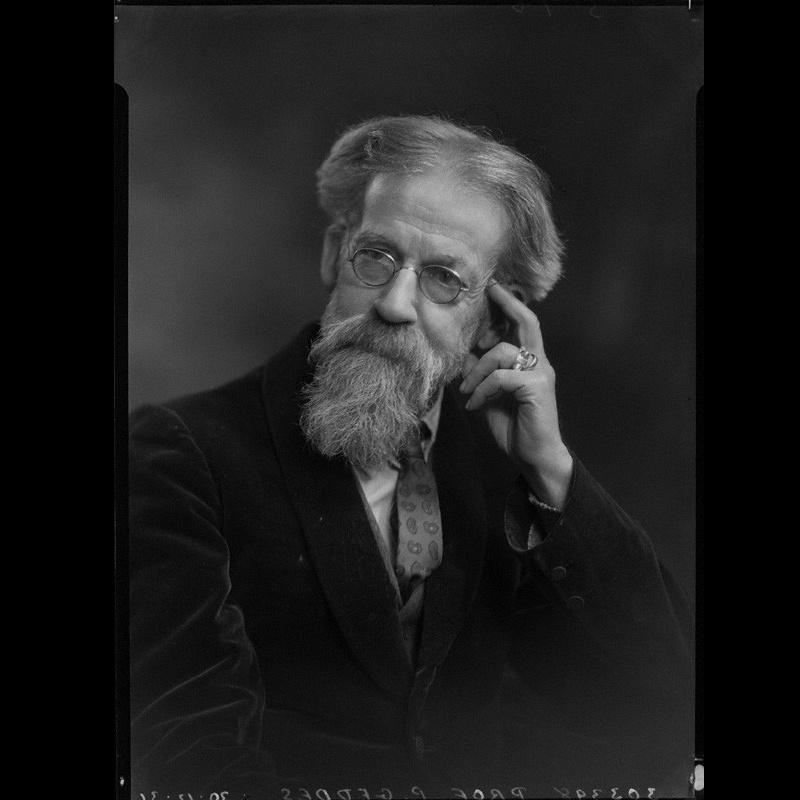

Sociologist and pioneering town planner Patrick Geddes coined the term ‘temple-city’ after seeing the towns of Madras Presidency. As part of the ‘Reading a City’ series, we explore how Geddes saw the temple space as a focal point for settlements. (Photo Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, London/Wikimedia Commons)

In March 1919, a new term was coined when The Modern Review published an article called ‘The Temple Cities’[1] by Patrick Geddes.

For some scholars, monuments like the majestic temples of the ‘Tamil country’ (Tamilakam or ancient Tamil country refers to the geographical region inhabited by ancient Tamil people) illustrate specific styles, original or imitative. For others, they embody the ritual surrounding a sacred space. For still others, temples are what hold settlements together, giving them a focal point. Sociologist and pioneering town planner Patrick Geddes belonged to the last group.

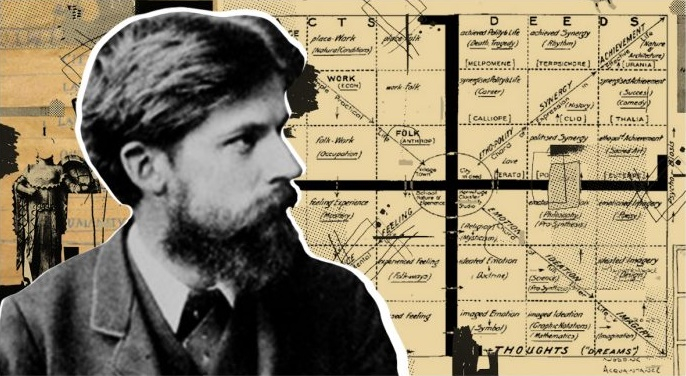

Cities, for Geddes, had distinct personalities.

Srirangam — The Temple City

An autodidact with a vast range of interests and endless curiosity, this visitor from Scotland could appreciate the finer points of Indian architecture, but what he found exciting was that he saw them as giving character and unity to towns. It was Geddes who coined the term ‘temple-city’ after seeing the towns of Madras Presidency.

Geddes admired Srirangam (now called Thiruvarangam, an island in Tamil Nadu’s Tiruchirappalli city) where, over time, the increasing population had been accommodated by building concentric walls. Further extensions could be done in the same design, he had suggested, substituting rows of tall trees for stone walls. Of Madurai’s wide chariot-roads he said, 'I can imagine nothing more helpful to city improvement than the re-establishment of car-routes, by a conjunction of Temple authorities and municipal planning office.' [2] The rath-yatra (or, in Indore, a Diwali procession) could be the occasion for the municipality and the community to clean up the city together.

Also read | How Cities have been Interpreted over Time

Srirangam was known for its 'atmosphere of idealism and learning'. [3] Geddes saw no need to build a new university campus there at great expense. Use the uncompleted gopurams (traditional temple structures), he had suggested. That on the south for classical languages, the northern one for astronomy, geography and natural sciences, that on the west for history, local, regional, Indian and ‘other’. The use for that on the east, he left to be chosen later.

(In 2018, unconsciously following this train of thought, Mumbai architect Brinda Somaya created a mind-blowing work of art in wood—a doll’s town, a gopuram, using its successive storeys for civic activities[S1]).

Using Space, Informally

For Geddes, India was a discovery and a vindication of his own tenets. In 1914, the first year of World War I, he had been invited to visit Madras (now Chennai) along with his popular exhibition on the evolution of cities. From then on, he spent 10 years on and off in India, travelling extensively across the country. He argued with British officials about the need to ‘improve’ Indian towns, with their twin formulae of piped water and sewerage (a century later, we are still echoing them), and straight metalled roads. Geddes suggested that it would be better to learn from Indians on how to ‘improve’ their towns. In India’s climate, curving lanes made more sense than wide straight roads, and trees made for convivial pauses in a street. Indian women, men and children created comfort-oases—under a spreading banyan tree, near a tank or on the bank of a river, at road intersections. Geddes’ photographs were not so much of buildings, but of informal use of space by people.

Also read | Cultural Plurality and Innovation in the Design of Temples in Bengal

'Our problem is first of all to read its history; that is to decipher its growth; and this not from books, but from its actual plan, and starting from the centre outwards,' Geddes had said.[4] Repairs and minimal realignments should be listed, and 'conservative surgery' (his phrase)[5] carried out. In his own Edinburgh, a dark angle between two buildings became a glowing Rene Magritte vision ('The Empire of Light') when Geddes inserted a slender wrought-iron street light.

Theoretical knowledge was not needed so much as observation. Too much specialisation, years of being mired in one skill/discipline, can narrow the mind. Geddes, the man without a college degree, who had leapt lightly from botany to biology, then to sociology, and to the study of the history of urbanisation, was accepted as a town planner in the way Le Corbusier and Satish Gujral, both artists, are recognised as architects.

Related | Lucknow isn’t Just Chikan and Kebabs; Sharar’s Essays Reveal its Spirit

Geddes’ infectious enthusiasm led scholars to explore and translate normative Sanskrit texts on the science of building and of layout—the vastushastra and shilpa shastras. But, in an atmosphere suffused with the powerful Modernist movement, this did not grow into a continuous project by classical scholars and architects (an unlikely pair at any time) to historicise or annotate them, as had happened in the European Renaissance. What survives is the sometimes comically simplistic notions of ‘vastu’.

This article is the fifth of a nine-part series on Reading A City by Dr Narayani Gupta on The Print.

Notes

[1] Patrick Geddes, ‘The Temple Cities,’ The Modern Review XXV (3): 213–222.

[2] J.V. Ferreira and S.S. Jha, eds, The Outlook Tower: Essays on Urbanization in Memory of Patrick Geddes (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1976), 468.

[3] Ibid., 475.

[4] P. Geddes ‘The Temple Cities’, J.V. Ferreira and S.S. Jha (eds.) The Outlook Tower: Essays on Urbanization in Memory of Patrick Geddes (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1976), 470.

[5] Geddes first used this phrase in his Great Cities Exhibition in 1911, together with the phrases 'diagnosis before treatment', both drawn from science.

[S1]A couple of words deleted here