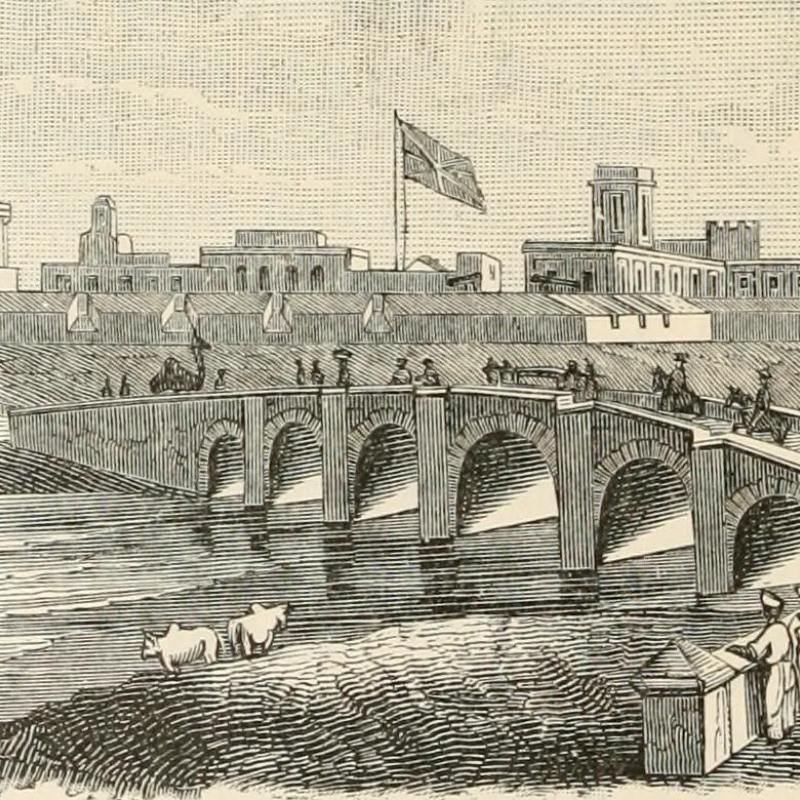

The past is in many ways a foreign country, and to walk through towns of the past slowly is an invigorating exercise. And there are those who can read them, see how they had grown. Some, such as Syed Ahmed Khan and Patrick Geddes, can use words vividly to conjure up other people in another time using the spaces we inherited. In this nine-part series, Sahapedia recalls the contributions of eight individuals to the renaissance of urban India. (In pic: Indika—The country and the people of India and Ceylon (1891); Photo Courtesy: Flickr [Public Domain])

There are cities on the ground, and cities of the imagination. There are rulers who wanted to be remembered for the cities they commissioned, which bore their names, and there are individuals who cherish memories of cities they had identified with, and have had to leave, for no fault of their own. Many Indians mourn the loss of Lahore, and there are people in Karachi dreaming about Delhi.

Today, more and more Indians are living in towns. Some speak of their gaon, nadu or ur. But there are families for whom the town is their home, though their share of it might be a very small sliver.

India's ‘democracy’ is best observed in a town—its strength lies in the freedom it implicitly gives individuals to build wherever and whatever, behind the veil of official sanctions and municipal bye-laws. Its weakness—the same. Any one kilometre along a major street is paved with instances of laws broken with impunity. Gautam Bhatia’s Stories of Storeys (2019) spells it out with frightening clarity. Is this how it will always be? Or will there come a moment of sanity, when we acknowledge our responsibility to respect public spaces, to share them and enjoy them?

There are those who can read cities, and see how they had grown. Some can use words vividly to conjure up other people in another time using the spaces we inherited. Others can see subcutaneous settlements below today's towns. Towns mutate constantly.

And there are those who can look at a stretch of land where man has not intervened—along a river, in the desert, on a mountain-top, looking out on an ocean—and visualise a city in the future.

There was a time, not so long ago, when people recognised qualities in India’s towns that inspired admiration, awe, as well as a sense of belonging. Certain skylines, silhouettes of buildings, the bank of a canal, majestic interiors, were easily recognisable, and tugged at your heartstrings. Imperial cities, named after their rulers, the monuments of which look as though they were built yesterday; cities which had prashastis (praises) written for them, and others which conveyed such a sense of pleasure that quotidian activities and interchanges were narrated in a spirit of joy; the city at different times of day and night—the stark landscapes of the world of the ‘underworld’, the bright lights and quiet of areas shaped by the rich. Each thinks they own the city, but in truth they only share it for a spell with those who form its framework—students, clerks, labourers and watchmen, shopkeepers…

The past is in many ways a foreign country, and to walk through towns of the past slowly is an invigorating exercise. Cities like Paris and London have inspired books on ‘sections’ of the city, over centuries. For India, we should extract all we can from books permeated with the spirit of the place, which in turn calls for understanding the author. Conversations with landscapes are not always recorded in images, and by the time a later generation reads these writers, their magic has been abbreviated to colourless sentences and drawings, and mediated by patronising interpreters. It is worth trying to recover the spirit in which Indian towns were read.

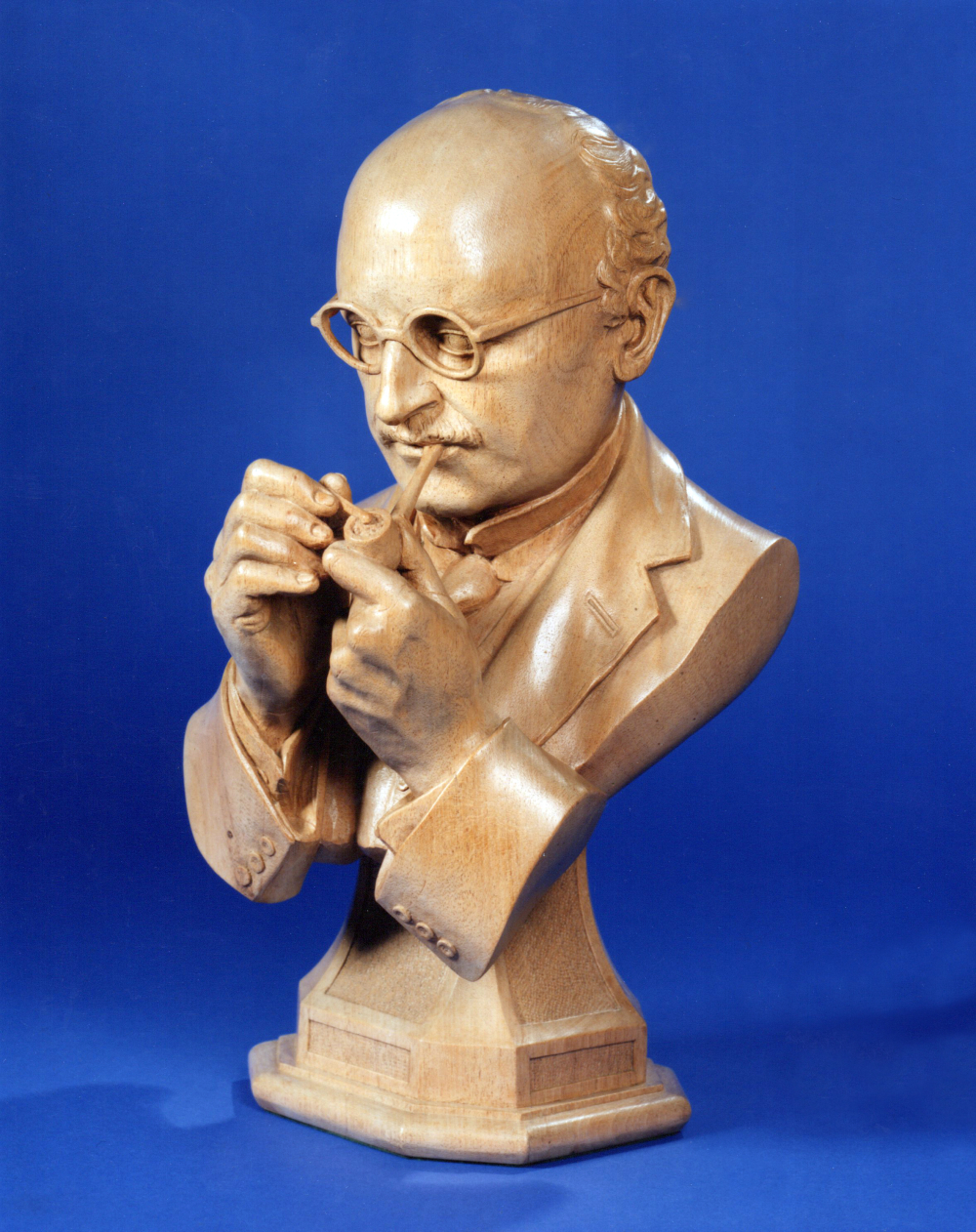

The 1840s was a watershed in urban history—it marked the beginning of modern urbanism, that which was the result of industrialisation, first in England and then in other parts of the world. The Indian subcontinent, with four millennia of urbanism behind it, also felt the winds of change. In some it prompted the urge to appreciate historic towns, in others the chance to see how the exciting new ideas being discussed in Europe and the US could be applied in India. Unstinted admiration for the organic Indian city came from the Scottish sociologist Patrick Geddes, and later from the Polish architect Matthew Nowicki. Happiness in the culture of the city was expressed by Lucknow's Abdul Halim ‘Sharar’. Delhi has had many admirers—Syed Ahmed Khan and Mohammed Mujeeb rejoiced in the majesty of its architecture, Gordon Sanderson the need to conserve these sensitively. Edwin Lutyens had the opportunity to create a new capital city, Mirza Ismael to ‘modernise’ the royal cities of Mysore, Hyderabad and Jaipur. For those interested in the history and reading of cities, looking at the contributions of each of these eight individuals to the renaissance of urban India would be highly recommended.

This article is the first of a nine-part series on Reading A City by Dr Narayani Gupta for The Print.