The Indian Muslim architect rejoiced in being ‘free’. He drew inspiration from a range of sources. As part of the series ‘Reading a City’, Sahapedia focuses on historian M. Mujeeb’s references to Indian Muslim architecture. (In pic: Chini ka Rauza in Agra; Photo courtesy: PersianDutchNetwork/Wikimedia Commons)

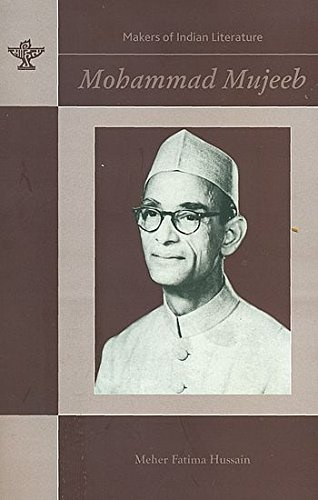

In the 1950s and ’60s, visitors to Delhi’s Qutub Minar often saw a crowd of schoolchildren following an unlikely Pied Piper, a frail man in a white kurta and pyjama, wearing a Gandhi cap, and giving them their first lesson in art history. Mohammad Mujeeb was one of those iconic professors who communicated just as easily with schoolchildren as he did with college students and his colleagues. He instilled in them a love for historic cities, made them see the places as works of art.

In those years, the Delhi skyline and groundline were dominated by monuments. For many families, these landscapes were synonymous with Sunday picnics. For art historians, these spaces became popular hunting grounds, and a number of case studies on architecture took shape in the 1970s.

Also read | The Keyis and the Odathil Mosque of Thalassery

But the lay reader was more familiar with surveys of Indian architecture. Of these, Percy Brown’s books were the most sought after. His volumes, Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu), and Indian Architecture (The Islamic Period), published in 1942, contain a mine of information. However, because he divided the theme in a binary, he missed out on capturing the special quality of the fourteenth–seventeenth centuries—the cosmopolitanism in architecture—when rich and powerful rulers, irrespective of religion, engaged skilled artisans and engineers from across south and west Asia to design beautiful public spaces.

Architectural Crossover

In that era of increasing globalisation, artisans met and exchanged recipes for architectural design, and travelled great distances, confident of their patronage. Guilds from the Middle East were employed to design the great pillars of Yorkminster, and Indian stone-masons learned structural engineering from Uzbek architects. Chinese porcelain gave its name to the funerary monument Chini Ka Rauza (China Tomb) in Agra. British tourists to Italy brought back fragments of Roman sculpture to display proudly in their country estates, while Feroz Shah Tughlaq had two Ashoka pillars (only no one knew what they were) ferried to Delhi from Meerut and Topra (Haryana), to embellish his mosque and his estate on the Ridge.

James Fergusson, in the mid-nineteenth century, had sought to make sense of the myriad buildings in India. He found it simplest to classify them by ‘style’. Function, it was assumed, shaped the form, and buildings were labelled ‘Buddhist’, ‘Hindu’ or ‘Islamic’. The term ‘Indo-Saracenic’ was coined to describe styles with elements of both, as well as for the British imperial style, which deliberately included decorative Indian elements. In this anxiety over labels, the buildings lost some of their power to evoke wonder and surprise, to speak to the hearts and minds of the people.

Indian-Muslim Architecture

Both mosques and tombs adopted from and adapted to the local environment, which is why Mujeeb insists that they be described not as ‘Muslim’ but as ‘Indian Muslim’. They, and other public areas—streets and walled gardens—made for beautiful cities, with a quality of repose and of camaraderie. Soaring arches and minars (towers) connected the earth to the sky, to heaven. (Mujeeb was too much of a rationalist to fall for the belief that djinns lived in historic buildings and could fulfil people’s prayers.)

Communal practices do shape houses of worship—and there is a fundamental difference of form between a congregational masjid (‘beauty without mystery’) and a mandir, where there is mystic communion between deity and worshipper. As for the tomb: ‘[It] was a symbol of unifying life, death and eternity; primitive beliefs associated with kingship gave the royal tomb a mysterious significance. . . The tomb of a ruler was the expression of personality, of a force which the community needed to maintain its self-confidence in a world of conflicts,’ Mujeeb wrote in The Indian Muslims (1967).[1] He was not averse to sounding tongue-in-cheek while describing Humayun’s mausoleum: ‘There is nothing we know of Humayun that would justify our regarding him as an outstanding personality; his tomb is much greater than he.’[2]

Related | Why Delhi’s monuments will always remember archaeologist Gordon Sanderson

The urban architecture of early modern India has some of the features of Persian or Turkish cities, but is most similar to those of Rajput kingdoms, contemporary with those of the Mughals. Both were shaped by the climate, conditioned by topography, the fact that they were built by skilled stone-masons rather than brickworkers, and by the deliberate choice of Indian ornamental motifs.

The Indian-Muslim architect rejoiced in being ‘free from the beginning, free from fear and hatred, from law and custom, from the conflicts of ideals and interests. There were no limits fixed except those of his own aptitude and means, and the nature and availability of structural material.’[3] They created an architecture that was not just frozen music, but also frozen poetry. It was both the architecture of Urdu poetry and the poetry of our architecture that made cities in India the grandest in the early modern age.

This article is the eighth of a nine-part series on Reading A City by Dr Narayani Gupta on The Print.