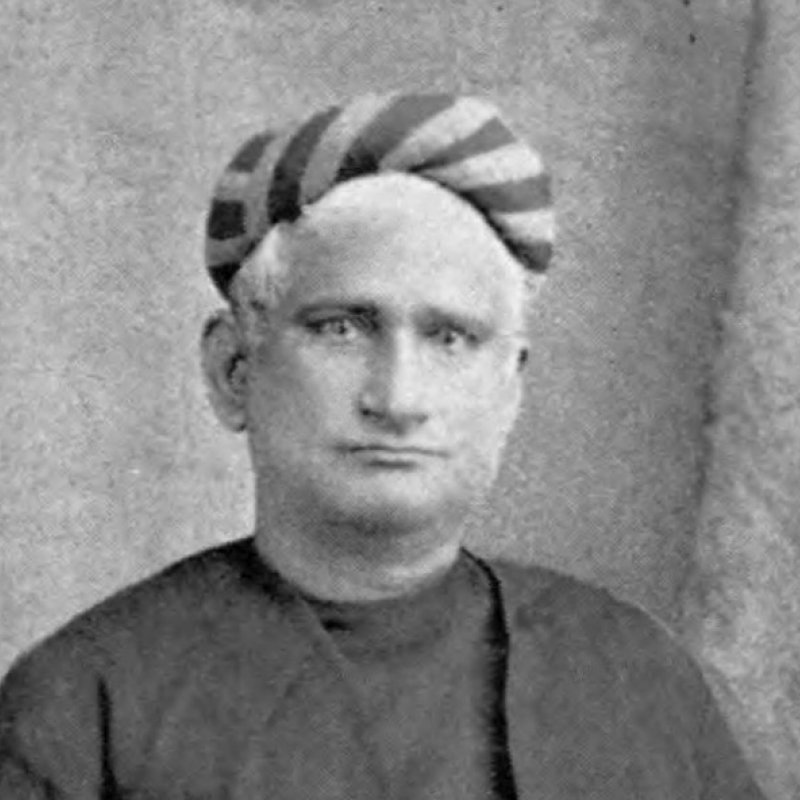

Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay was not only a literary pioneer in Bengali, but an activist whose words and work are seminal for meaningfully interpreting the West for India and India for the West. We look at how his ideas on contemporary Hindu society and culture reveal a curious mix of liberality and conservatism. (Photo Source: Sibnath Sastri/Wikimedia Commons)

The life and works of Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay (1838–94) represent some of the most vital aspects of Hindu–Bengali life and culture in the late 19th century, such as their intellectual creativity and emotive passion, social anxieties and political ambitions, a positive energy and reactionary self-defence. He was one of the first two to graduate from Calcutta University and was promptly offered employment in the provincial civil services. As a man equally well-read in the philosophical discourse of post-Enlightenment Europe and indigenous tradition, he attempted to meaningfully interpret the West for India and India for the West. In hindsight, it appears as though of the two enterprises, the former was perceptibly more successful.

Towards the end of his life, growing bureaucratic discrimination, racial arrogance and sharper social and political inequalities emerging in a colonised world made him more cautious, circumspect and in some ways, culturally apologetic. In the 1880s, he was drawn into protracted controversy with Christian evangelists who expressed contempt for heathen ‘superstition’ and idolatry and even Indian reformist groups like the Brahmo Samaj whom he accused of thoughtlessly aping the West.

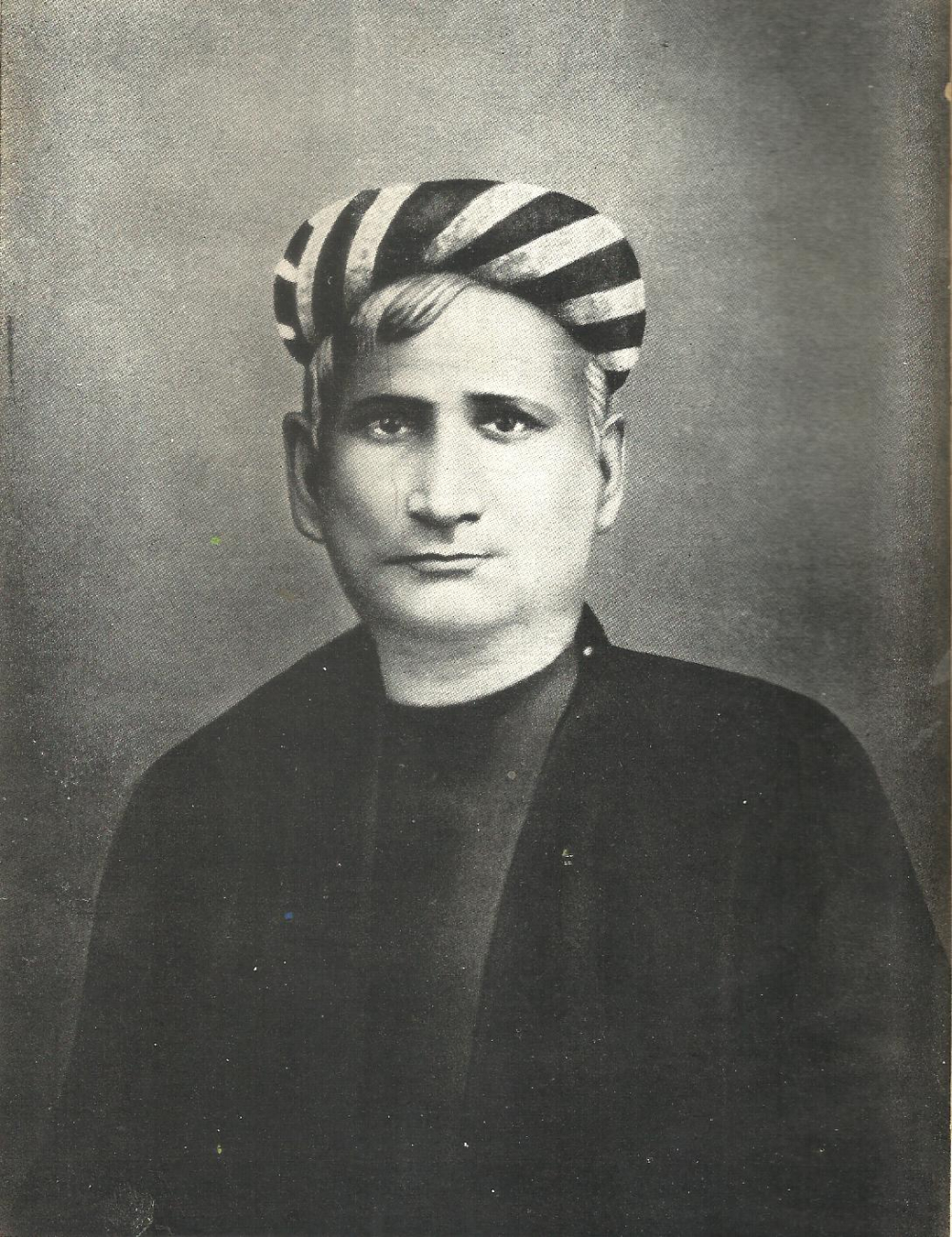

Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay edited a Bengali monthly called 'Bongodarshan', which took Bengali journalism to new heights and substantially contributed to the development of the Bengali language and literature (Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Later in life, Chattopadhyay was anguished by the way Western society and scholarship had misapprehended and misrepresented India and Indians. When asked to translate some of his popular novels into English, he declined to do so, alleging that with their limited understanding of India and its institutions, Europe was more likely than not to cast unjust aspersions on Hindu practices. For instance, the taking of a second wife could be misconstrued as a polygamous habit, whereas it was simply a practice common to upper caste, aristocratic society and not rooted in sheer sensuousness or the bodily needs of the male.

Whether in Bengal or elsewhere, Chattopadhyay is known as a pioneer and a successful novelist. In all, he wrote about 15 novels and numerous essays. The Bongodarshan, a Bengali monthly he edited for a number of years, took Bengali journalism to new heights and substantially contributed to the development of the Bengali language and literature. Widely circulated in urban households, this journal opened up new vistas of knowledge for its readers, familiarising them with history, philosophy, religion, literature and popular science. Some of his romantically charged novels found a good number of female readers.

Related | Perspectives on Caste: The 19th Century Bengali Literati

Chattopadhyay was also instrumental in alerting the Hindu Bengali intelligentsia of the moral and intellectual challenges thrown at the Indian mind by the contemporary West and the unique experience of colonised subjection. He could clearly perceive that India as a country was being increasingly drawn into extractive global capitalism and modern ways of life but for which the country was rather ill-prepared. Chattopadhyay’s greatest gift to his contemporaries though was the hermeneutic attempt at suitably redefining his own tradition in the light of some unprecedented challenges. He performed this by adopting a historical and dynamic view of tradition and one that was to be judged by contemporary notions of reason and utility. In locating an urtext for the Hindus comparable to the Bible for Christians and the Koran for Muslims, Chattopadhyay settled upon the Bhagavad Gita.

He significantly subjected this ancient, canonical text to modern methods of textual criticism and his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, though respectful of classic commentators like Adi Sankara, sharply disagreed with their views. The belief that traditions evolved with time allowed Chattopadhyay to adopt a dynamic, rather than a static view of the past. He answered Western–Christian critiques of Hinduism by projecting the Hindu deity Krishna as both god and man. Just as Europeans like David Friedrich Strauss and Ernest Renan had reconstructed a historical Christ through Biblical criticism, Chattopadhyay produced in his magnum opus, the Krishnacharitra (1892) a much sanitised Krishna, having discarded a bewildering mass of medieval folk and classical literature allegedly burdened by myths and irrational accretions. On the whole, Chattopadhyay was religious and unlike several forbearers believed in God incarnating in human form and in divine interventions in history. In 19th century India, this helped end the great influence that deism once had on the Hindu mind.

Even though Chattopadhyay bemoaned Hindu ‘excesses’, obscurantist practices and advocated female education, he was one of the staunchest opponents of widow remarriages (Photo Source: Biswarup Ganguly/Wikimedia Commons)

It is often overlooked that some of his early writings were on popular sciences. Elsewhere too, he encouraged Baconian methods of observation and inductive reasoning. His interest in emerging disciplines such as anthropology and sociology enabled him to interpret Hindu ideas and practices in a new light. For instance, he related the origin of Hindu festivals to agrarian production cycles and not to religious myths. Though essentially a vernacular scholar and intellectual, Chattopadhyay was on the side of Western Education and modern forms of knowledge. This connects him to both Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1764–1833) and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820–91) who discouraged state patronage of traditional Hindi education. It must be admitted though that he was also critical of certain Western ideas or ideologies such as utilitarianism and positivism, both of which he found unsuitable for India.

Also Read | The Idea of Caste in 19th Century Bengal

Chattopadhyay’s ideas on contemporary Hindu society and culture reveals a curious mix of liberality and conservatism. He bemoaned Hindu ‘excesses’ and obscurantist practices, advocated female education and a new sensibility in gender relations. One of his female characters in the novel Krishnakanter Will (1878) is heard to say that only that man ought to be respected as a husband as deserved that respect. On the other hand, in the late 19th century Bengal he was one of the staunchest opponents of both widow remarriages and the legal abolition of multiple marriages among men. In his essay Dharmatattwa (1888), he draws a parallel between a devotee’s reverence for God to the love and loyalty a woman ought to have for her husband.

Chattopadhyay is also rightly associated with the burgeoning Hindu nationalism in his day, a sentiment which often resurfaces in his several novels such as Anandamath (1882), Sitaram (1887) and Rajsingha (1882). And yet, he appears to have uncritically accepted British colonialist portrayal of India’s past, particularly the vilification of Indo-Muslim rule and the accompanying belief in the British having rescued India from tyranny, ignorance and oppression. In some of his novels, Muslims are made the scapegoats, an approach which only further sharpened the communal divide between the Hindus and Muslims in the years to come.

The cry of ‘Vande Mataram’ was essentially directed at the urban, middle-class Hindus, apparently excluding both non-Hindus and the Hindu depressed castes who mostly inhabited rural spaces and exhibited a very different culture. It is also often overlooked that Chattopadhyay did not envision a fully de-colonised India—an attitude that is partly explained by his serving the colonial bureaucracy. However, in his novel Anandamath he did make the important point that Indians first ought to bring themselves up to the level of knowledge and skills that the British themselves had acquired before prematurely taking to an armed and violent struggle against an alien ruling class and the colonialist state.

Such inner ambiguities and tensions in the 19th century Bengal were poignantly represented in Chattopadhyay’s life and work. It was a time when accepting Western forms of modernisation had to be delicately balanced with serious self-reflexivity and cultural introspection. It is to Chattopadhyay’s credit that he performed this task quite admirably.

Views expressed are personal.