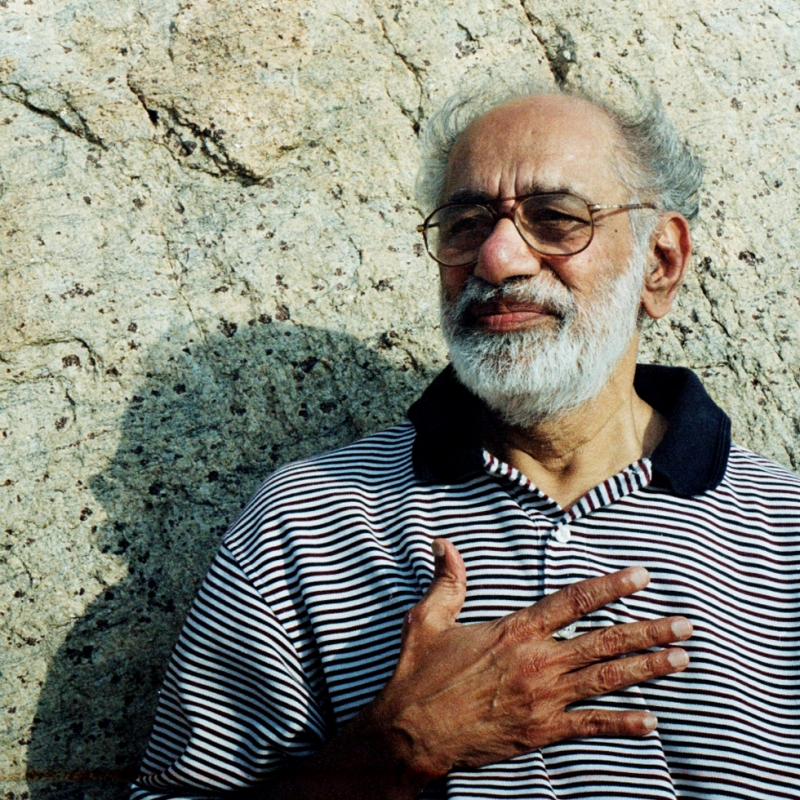

Sundara Ramaswamy was born in 1931 in Nagercoil, then part of the princely state of Travancore. He grew up in Kottayam and, later, central Travancore until the age of eight, when his family moved to Nagercoil in 1939 just as the news of the World War II was breaking out. Sundara Ramaswamy spent the rest of his life in the town of Nagercoil, passing away in 2005.

Situated barely 20 km from the Indian peninsula’s southernmost tip, Kanyakumari, its district headquarters was described once as ‘the last outpost of Indian literature’. It was not until 1956 that Travancore was reorganised as part of the modern Kerala state. The Tamil-speaking regions of south Travancore—present-day Kanyakumari District—joined the then Madras State, now Tamil Nadu, in the same year, after a bloody, popular struggle.

Growing up in the cultural intersection of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, Sundara Ramaswamy grew up ‘half-knowing’ Malayalam, Sanskrit, and English. An attack of juvenile arthritis and subsequent indifferent health (a recurring theme in his writings) saw him barely reach the school final. Tamil, which he used with such consummate mastery and nuance, he did not learn until he was about 18.

This bilingual milieu—of Tamil and Malayalam—is central to Sundara Ramaswamy’s writing, and he is one of the few writers in India who is widely regarded in two linguistic cultures as their own. Ramaswamy was introduced to the path-breaking writings of Malayalam’s greatest writers at the first signs of the dawn of modernism in Malayalam literature. His first literary endeavour was to translate Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s Thottiyude Magan (The Scavenger’s Son) into Tamil. His translation of another of Thakazhi’s novels, Chemmeen, continues to be in print half a century after its first publication. Sundara Ramaswamy was closely associated with M. Govindan, the offbeat Malayalam cultural critic, and maintained intimate relationships with many Malayalam writers. He translated many Malayalam poems into Tamil and kept Tamil readers informed of cultural happenings in Kerala with his comparative commentary. When Sundara Ramaswamy passed away, the leading Malayalam daily, Malayala Manorama, wrote in its editorial that his death was a loss to two language communities.

Literary Career

Sundara Ramaswamy made his literary debut in late 1951, with the publication of an edited volume in memory of Pudumaippittan (1906–1948), the fountainhead of Tamil modernity, and an undying influence on his work.

In the early 1950s, Sundara Ramaswamy was drawn to the (undivided) Communist Party of India and came to know P. Jeevanandam, its leader and litterateur, a charismatic personality and legendary orator. Another key influence was T.M.C. Ragunathan, progressive writer and biographer of Pudumaippithan.

Sundara Ramaswamy’s early fiction was published in progressive literary journals. He made his mark with short stories in the monthly Shanthi (1954–56) edited by Raghunathan. After Shanthi folded up, he continued to write short stories in another progressive literary journal Saraswathi (1955–62). His first novel was also serialised in this monthly. Saraswathi, edited by the communist thinker V. Vijayabaskaran, was an exciting journal marrying art with Left politics. But in the years following Khrushchev’s secret address to the Communist Party of Soviet Union’s XX Congress, exposing the brutalities of Stalin’s regime and the crushing of the democratic Hungarian Uprising (1956), Sundara Ramaswamy distanced himself from the Left movement. These were difficult times when, with the sectarianism characteristic of the Left, he was isolated and subjected to calumny—this continued to colour the Left movement’s relationship with him until his death nearly half a century later.

Around this time, Sundara Ramaswamy came in contact with Ka. Naa. Subramanyam, a writer of the Manikodi group who had a controversial reputation as a literary critic for celebrating ‘art’ and running down popular writing and agitprop. Sundara Ramaswamy held him in high esteem, despite the many differences between them. As he moved away from the Left, Sundara Ramaswamy increasingly identified himself with the avant-garde modernism that functioned through little magazines. This moment also coincided with the growing hiatus between popular literature appearing in mass magazines and self-conscious art in little magazines, and a widening rift between progressive literature and the little magazines. The little magazines were also a reaction to a dominant strand of Tamil identity politics that had a strong non—if not anti—Brahmin streak to it.

Although never prolific, Sundara Ramaswamy kept a consistent stream of free verse (he is considered one of the most prominent poets of the literary monthly Ezhuthu, edited by C.S. Chellappa), and critical and polemical essays. Employing the pseudonym ‘Pasuviah’ for his free verse, his early poetry is memorable for its declamatory style. With occasional bursts of poetry, he wrote a little over a 100 poems in his career, most of them short and still recalled by readers. With the folding up of Saraswathi, he published in the little magazine Deepam edited by the popular writer Naa. Parthasarathy; it was under his editorship that he also published in the popular weekly, Kalki.

First Novel

In 1966, Sundara Ramaswamy completed his first novel, Oru Puliyamarathin Kathai (The Tale of a Tamarind Tree), which combines oral lore and history to narrate the story of change in a small town. The tamarind tree is the central character until it falls prey to the machinations of local business and politics and is ultimately poisoned to death. The disillusionment of the post-Independence era is writ large over this novel, and it manifests an acute understanding of time and the changes its passage ushers in through human agency. In this narrative, oral lore and folk traditions are skilfully woven. Characters are carefully etched with a clear sense of their social location. The narrative brims with humour and satire and the dialogues convincingly capture the dialect of the region for the first time in Tamil literary history. One of the earliest dialect novels in Tamil, it successfully employed the demotic language of the region. Oru Puliamarathin Kathai remains a classic despite being ignored by contemporary critics. The publication of this novel marked the end of the first phase of his writing, a phase characterised by the combination of social criticism and artistic refinement.

The Interregnum and After

What followed was an interregnum of silence lasting seven years until 1973. Sundara Ramaswamy announced his return with the combative ‘Savaal’ (Challenge), arguably one of the most quoted of modern Tamil poems, in the little magazine Gnanaratham. His short stories of the time, collected and published in book form, Pallakku Thookkikal, reveal a tighter language and a conscious attempt to experiment with form and content. His later oeuvre of short fiction alternates between the storytelling of the first phase and the experimentation of the second phase. In all, Sundara Ramaswamy wrote around 80 short stories, in which definite shifts in his writing style and a determination not to repeat his artistic successes can be easily discerned.

Ever a stylist, employing a language, consciously crafted—shorn of traditional rhetorical devices, but brimming with satire, parody, humour, and metaphor—Sundara Ramaswamy’s enquiring perspective marked him out distinctly. By the 1970s, he was the figure that the progressive literature camp loved to hate. Further, Sundara Ramaswamy developed an increasing dissatisfaction with the state of Tamil literature and culture.

J.J.: Sila Kurippukal

Despite his artistic success with short stories, what made him a literary hero of sorts was his second novel—J.J.: Sila Kurippukal (J J: Some Jottings). In its form and content—the studied mastery and precision of its language, and the sensitive and provocative formulation of ideas— the novel was a rupture in the narrative tradition of Tamil fiction. The novel structured, complete with footnotes and appendixes, as the biography of a fictional Malayalam writer, Joseph James (J.J.) created a literary sensation.

The Tamils—like the English, but unlike the French—do not have the stomach for ideas dressed up as literature. J.J.: Sila Kurippukal is a single swallow in that Tamil literary–intellectual summer. Its literary brilliance notwithstanding, it is very much a novel of ideas.

Appearing in 1981, the novel with its overt intellectualism created a stir. Since then, despite a poor distribution, in the beginning, the novel has entered its 19th edition, which is a considerable achievement by the standards of serious Tamil literature. Almost every reader of that time would remember the shock and exhilaration the novel caused on its first reading. The clever way in which the novel is structured—almost a Künstlerroman (novel narrating artist’s growth to maturity), complete with notes and appendixes of the fictional Malayalam writer— left readers gasping. The detailed depiction of the Malayalam literary world, while being rather novel, simultaneously triggered the search for Tamil parallels. Unfortunately, many readers got lost in this wild-goose chase, missing the import of the novel. The novel is nothing less than a thoroughgoing critique of Tamil culture and society and, by extension, much more. With the pretext of talking about the Malayalam literary world, the novel indulges in deep introspection of Tamil culture. Wrestling with the pressing philosophical questions of its time, it provides insights into ideas, institutions and individuals, and the souring of idealism.

J.J.: Sila Kurippukal, therefore, represents Sundara Ramaswamy at the peak of his writing prowess.

Last Novel

Sundara Ramaswamy wrote one more novel. After the dazzling J.J.: Sila Kurippugal, readers wondered what he would offer next. In 1998, he published Kuzhandhaigal Pengal Aangal (Children, Women, Men), a tome compared to the slim volume of his earlier two novels. And uncharacteristically, it was set in a family, within the four walls of a home. At a time when postmodernism was a rage in Tamil literary circles, and the death of realist writing was being declaimed from rooftops, and writers were experimenting with non-linear narratives and metafiction, Sundara Ramaswamy opted for a deceptively direct narrative.

Set in the years before the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, it is transparently autobiographical with a large dose of intertextuality evident to a reader of his earlier work. The narrator of J.J.: Sila Kurippugal, the Tamil writer Balu, figures as a boy and a major character. The long novel narrates incidents and ruminations in a Tamil Brahmin family in Kottayam, torn as it is by the cataclysmic changes unleashed from political and social forces from all over the world, over which the characters have little control. Written in over 100 short chapters, which can be seemingly dropped or interchanged, the reader can almost dip into the novel at any point. Underappreciated by readers and critics alike, its artistry is deceptive, concealing great craftsmanship.

Essays

Sundara Ramaswamy started writing essays only mid-career. At the invitation of Ka.Naa. Subramanyam, in 1963, he wrote his first essay—on his engagement with Subramania Bharati. For the next two decades, he wrote essays occasionally; during the 1970s, in the heyday of the little magazine, he also indulged in polemics. Though much of it has lost relevance, his critical review of Akilan’s novel Chitrapavai when it received the Jnanapith award (1975) is a classic. Sundara Ramaswamy's eponymous first collection of essays, published in 1984, was a slim volume with just 15 essays and included a list of another 10. These numbers were to change dramatically in the next decade and a half, and his views would win him both cloying admirers and vicious detractors.

In the early 1990s, Sundara Ramaswamy withdrew from his family business, a retail textile shop started by his father at the time of the Second World War, and handed over its reins to his son. Sundara Ramaswamy’s lifelong dream of devoting time entirely to writing and contemplation was now a reality. From the early 1990s, Sundara Ramaswamy began to spend time, annually, with his wife, in Santa Cruz, California (later dividing his time at his youngest daughter Thangu’s home in Connecticut), and read and wrote in near solitude.

This period also marked Sundara Ramaswamy’s emergence as a public intellectual. His early youth in the decade immediately after Independence had been spent in public, attending cultural events, and affiliated to the Left progressive movement. His distancing from the Communist Party in the early 1960s was followed by immersion in a narrow literary world, cut-off from the larger public sphere. This changed dramatically at the turn of the last decade of the last millennium.

In February 1992, early in her first term as Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, Jayalalithaa visited the temple town of Kumbakonam during the once-in-12-years Mahamakam festival. Enjoying her newfound Z-plus security, her callousness in the midst of crowded watershed led to a stampede. Over 50 pilgrims died and many more were injured, a tragedy worsened by Jayalalithaa’s lack of remorse. An angry Sundara Ramaswamy shot off a searing op-ed article to Dinamani, terming it a padukolai—a massacre. Dinamani’s editor Kasturi Rangan decided to carry it in the literary monthly Kanaiyazhi rather than in the mass-circulated daily. From that time, Sundara Ramaswamy maintained a steady stream of essays and reviews.

The Last Phase

The early 1990s was a period of turbulence in India. The fragmentation of polity, the economic crisis and liberalization of economy, Masjid–Mandal, the break-up of the Soviet Union and the crisis of the Communist parties, Ambedkar’s birth centenary and the rise of Dalit literary movement underpinned this churning. The Tamil intellectual world was sucked into this.

Never one to jump on the bandwagon, Sundara Ramaswamy critically engaged with new ideas and trends. Open to new ideas, he was also ill at ease with regurgitation of undigested ideas and questioned half-baked ideas that masqueraded as postmodernism. Unlike other contemporary writers, he read the work of younger writers and commented on them. In the 1990s, new journals emerged and he used these avenues to express his views. Using the newly opened up leader pages of Dinamani, he expressed views which ruffled many feathers. For instance, criticising the hugely celebrated film actor Sivaji Ganesan for his theatrical histrionics, Sundara Ramaswamy wondered if he had ever factored in the powerful lens that stood between the actor and the audience. The readers of that time can also recall that he had once described MGR as a clown.

In the 1990s, he enjoyed robust health, something he said he was not used to his entire life. He was an active correspondent, writing letters every day. At one time, he even maintained a steady correspondence with a TADA convict which drew unwarranted attention from the state, but he was not deterred.

Sundara Ramaswamy was legendary for being parsimonious with praise. Authors who sought his endorsement became angry when it was not forthcoming, and the enemy camp swelled. When he occasionally lauded the work of a young writer, it only infuriated other writers.

In 1987, he had launched a literary review, Kalachuvadu, which folded up in two years, after publishing eight substantive quarterly numbers, and a bumper signing-off number. In late 1994, his son revived Kalachuvadu in a different form. Within a year, he had also launched a publishing imprint of the same name, primarily to publish Sundara Ramaswamy’s writings, and to publish reliable editions of the collected works of Tamil modern greats such as Pudumaippithan and G. Nagarajan. Despite his reputation, Sundara Ramaswamy had been unhappy that his works were out of print most of the time, and these developments gave him energy to write anew and consolidate older work. For instance, his earliest effort, the translation into Tamil of Thagazhi Sivasankara Pillai’s Thottiyude Magan, was retrieved from old volumes of Saraswathi and published in book form. The response of readers, starved of his writings for decades, delighted his heart and gave him the energy to crank up his literary production.

With his strong views and uncompromising stance, Sundara Ramaswamy was the object of vicious and motivated criticism, complicated by the fact of some of his self-proclaimed protégés turning against him. The success of an international Tamil literary conference—Tamil Ini 2000—that Kalachuvadu organised in September 2000, widened the fault lines. Sundara Ramaswamy was forced to expend his energies writing rejoinders, clarifying his views, and correcting willful distortions.

Sundara Ramaswamy was passed over for many awards. The only real award, despite the minuscule purse that came with it, was the Asan literary prize, named after the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan. In the last years of his life, the University of Toronto conferred on him the inaugural Iyal Award, for lifetime contribution to Tamil; and the Delhi-based publishing house and NGO, Katha, awarded him the Katha Choodamani.

In February 2005, he published ‘Pillai Keduthal Vilai’, a short story about a resourceful lower-caste girl who gets educated and becomes a teacher. The resentful upper castes of the village charge her with seducing a student, and physically assault her. She goes missing for many decades, and returns as a recluse. Very much a vintage Sundara Ramaswamy story, it leaves the reader with a suppressed anger about the inequities of village life in a distant corner of the country, early in the century. A most unexpected response came from fringe elements who accused him of insulting Dalits (despite the fact that no Dalit character figured in it) and launched a campaign against him. Despite many prominent intellectuals rallying behind him, Sundara Ramaswamy was devastated. In the summer of 2005, he went on his annual visit to the US. He fell ill, was hospitalised, and died of pulmonary fibrosis in California on October 14, 2005. His diary jottings of the time make for painful reading. The spiteful attacks had hastened his death. The coffin was flown to Nagercoil, and his funeral, without any religious rites, was attended by one of the biggest congregations of Tamil writers ever seen.