The Hoysala dynasty, thriving in parts of Karnataka from around tenth century CE till the fourteenth century CE, developed their distinctive style of temple architecture, and the footprints of their work are still visible in the form of temples they built in Karnataka region. The herculean task of erecting such beautiful and ornate monuments was successfully carried out by the army of sculptors and architects of Hoysala dynasty.

It is inarguable that the sculptors are the real makers of architectural marvels even as they remain shrouded in mystery and are seldom appreciated. Their individuality is frequently masked as they are deemed as a singular entity without identity, as creators of unmarked and unsigned work. In this context, Hoysala temples are an exception, as most temples of the period display signed works of sculptors. This fact was first brought into light by scholars like B.L. Rice, R. Narasimhachar, M. H. Krishna in their systematically observed and well-analysed publications on Hoysala temples and inscriptions, where they observed personal signatures of the artists who created the sculptures.

The thirteenth-century Hoysala temple, Lakshmi-Narasimha temple, situated in Harnahalli village of Hassan district, 35 km away from Hassan city in Karnataka, is no different. It was constructed during the reign of Hoysala king Narasimha II Ballala in 1234 CE, as stated by the Annual Report of Mysore Archaeological Department, 1933, by three brothers with permission from their father, Svami of Sindige Mutt,[1] and carries magnificent examples of Vaishnavism-influenced sculptures with names of their architects boldly displayed alongside.

Signature of the Sculptors

The chief architect of the temple was responsible for the entire design of the temple, including the preparation of its plan, decoration of the exterior walls and towers, as well as the arrangement of pillars and relief design.[2] There must have been various intentions behind signing the names of sculptors. In most instances, these signatures include several other details along with the name of the chief sculptors like details of his family, his guild, place of origin and payment. The utilitarian purpose behind signing the names and places of their origin might have been advertisement of their work.

The Lakshmi-Narasimha temple, Harnahalli, displays the signatures of several artists, mostly on the pedestals of the sculptures on the circumambulatory path. According to observations by scholars, Mallitamma seems to be the chief sculptor of the temple. The name Periyanda Heggade also appears on the pedestals of a few sculptures; under some sculptures, there are signatures with only two syllables which were probably their initials, Bo la and Ba na. In Hoysala temples, amid large-scale sculpting activities where many sculptors worked simultaneously, carving only initials of the sculptors’ name was probably for easy assessment for correct payment of artists’ work.

All the inscriptions in Lakshmi-Narasimha temple are in Halekannada script. The inscription with the foundation information is carved on the beams near the ceiling of the mukhamandapa (an entrance hall). There are 34 label inscriptions over the pedestals of images on the circumambulatory path of the temple, out of which 22 are of Mallitamma, six are signed as Bo, three are of Periyanda Heggade (Fig. 1) and two are signed as Ba na.

|

Sr. No. |

Sculpture |

Signature of Sculptor[3] |

|

1. |

Hanuman |

Ba na |

|

2. |

Lakshmi |

Ba na |

|

3. |

Attendant |

Periyanda Heggade |

|

4. |

Attendant |

Periyanda Heggade |

|

5. |

Madhava |

Bo |

|

6. |

Attendant |

Bo |

|

7. |

Attendant |

Periyanda Heggade |

|

8. |

Rati |

Bo |

|

9. |

Kamadeva |

Bo |

|

10. |

Rukmini |

Bo |

|

11. |

Panduranga |

Bo |

|

12. |

Saraswati (Consort of Sankarshana) |

Mallitamma |

|

13. |

Sankarshana |

Mallitamma |

|

14. |

Garuda |

Mallitamma |

|

15. |

Priti (Consort of Pradyumna) |

Mallitamma |

|

16. |

Pradyumna |

Mallitamma |

|

17. |

Aniruddha |

Mallitamma |

|

18. |

Rati (Consort of Aniruddha) |

Mallitamma |

|

19. |

Vasudha (Consort of Purushottama) |

Mallitamma |

|

20. |

Garuda |

Mallitamma |

|

21. |

Attendant |

Mallitamma |

|

22. |

Harihara |

Mallitamma |

|

23. |

Parashurama(?) |

Faded |

|

24. |

Vidhula (Consort of Narasimha) |

Mallitamma |

|

25. |

Narasimha |

Mallitamma |

|

26. |

Mahishasurmardini |

Mallitamma |

|

27. |

Attendant |

Mallitamma |

|

28. |

Attendant |

Mallitamma |

|

29. |

Attendant(?) |

Mallitamma |

|

30. |

Attendant |

Mallitamma |

|

31. |

Attendant |

Mallitamma |

|

32. |

Krishna |

Mallitamma |

|

33. |

Buddhi (Consort of Krishna) |

Mallitamma |

|

34. |

Narayana |

Mallitamma |

Chief Sculptor: Mallitamma

The chief sculptor of Lakshmi-Narasimha temple, Mallitamma was a very distinguished sculptor during the Hoysala period with his career spanning nearly 73 years. His name appears on several temples such as Amriteshvara temple of Amritapur; Lakshmi-Narasimha temples of Javagal, Harnahalli and Nuggehalli; Panchalingeshvara temple of Govindanahalli; and Keshva temple of Somnathpura. According to Kellson Colleyar, Mallitamma might not have carved each and every image at the temples because when the Keshava temple was being built, he must have been in his nineties or older, which makes it inconceivable that such an old man would carve such intricate sculptures. Hence, it is very plausible that he might have set up a workshop at the site, and the sculptures were crafted according to the designs by Mallitamma. (Fig. 2)

Classical Literature and Sculptures

The sculptors conformed to the sculptural norms mentioned in the shilpashastras (texts with guidelines for crafts) which guided their construction at that time. The texts contained the directions and estimates about sculpting images, temples, forts, gateways, houses, etc., and laid down rules and regulations about performing certain ceremonies and information about auspiciousness of particular sites. Manasara Shilpashastra specifically mentions that ‘all the buildings should be fully decorated by the architects.’[4] Likewise, there were steadfast rules for the construction of images in shilpashastras, and the more the image followed with the rules laid down by texts, the more aesthetically evolved it was considered: ‘…The form of god’s images must have to conform to the Dhyanas of gods found in the Puranas, Agamas or Tantras.’[5] It was also said that ‘an ugly place of residence could excite the god’s wrath, thus making the temple an extremely dangerous force,’[6] which probably explains the tremendous beautification of temples in Hoysala period. These manuals gathered knowledge over generations, and changes were incorporated into new texts as needed.

Chalukyan King Somesvara III’s encyclopaedic work Manasollasa has details similar to what is followed in the Hoysala style of art, from which it is safe to assume that either it played some role in the development of Hoysala style or it had similar source used by Hoysala artists. The stellate-shaped plan of the garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum), raised platforms on which the temples were built, profuse and minutely carved ornamentations of the sculptures, exuberant lathe-turned pillars, and usage of chlorite schist in the construction of temples were the trademarks of Hoysala style of temple architecture.

Ornamentation of Sculptures

The sculptures carved by Hoysala artists are manifestations of beauty and grace and are easily distinguishable because of the profusion of ornamentation in sculptures, which is a principle trait of Hoysala style. Every space in the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple is an evidence of the zealous nature of the sculptors, reflected in the abundantly carved shikhara, embellished pillars, beautified ceilings inside the temple, richly ornamented sculptures and minutely carved outer walls and doorjambs.

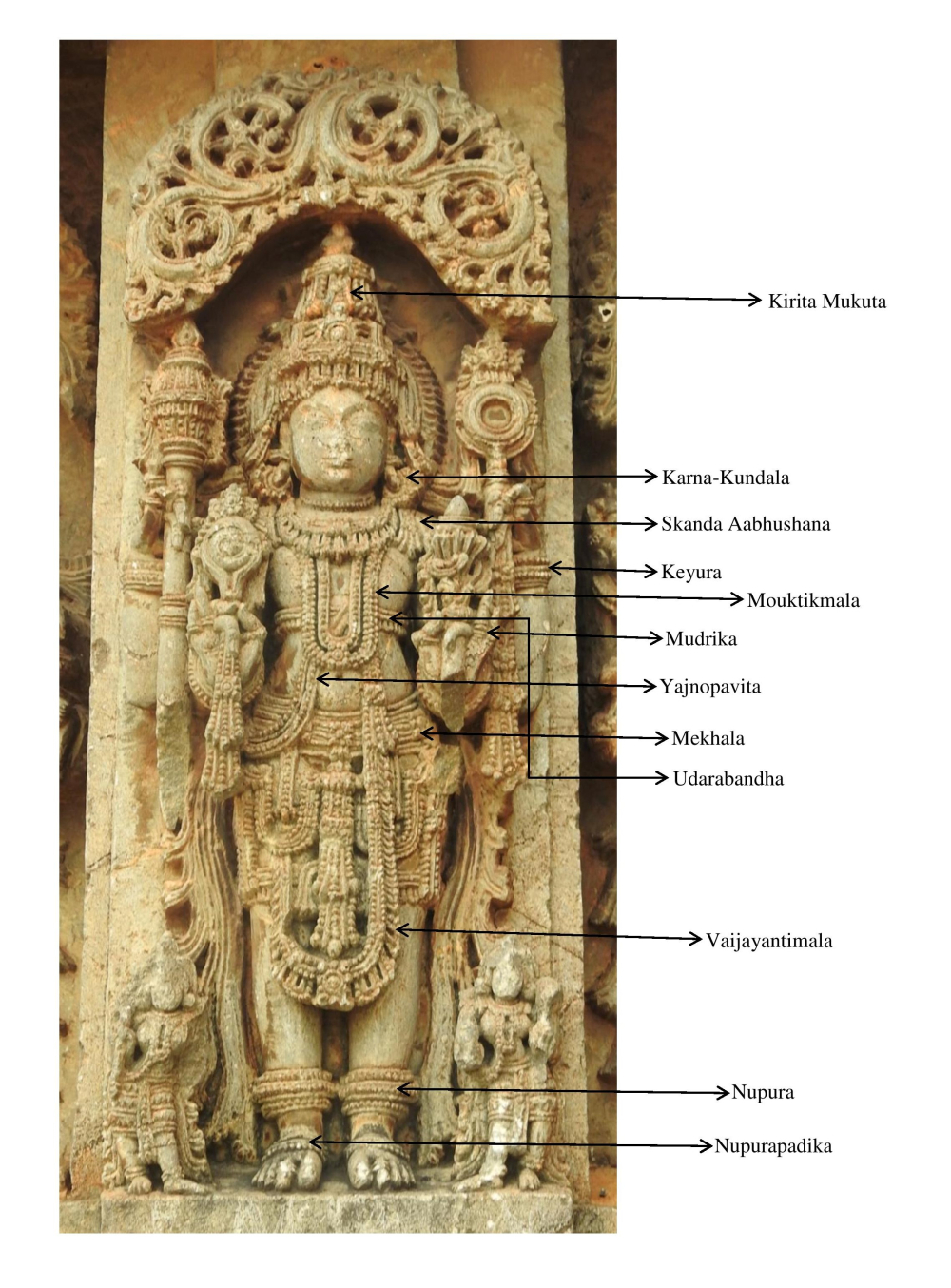

The abundant decoration is not limited to only female deities but also the male deities and even the mounts. For instance, a sculpture of Janardana on the outer wall of the temple is bedecked with a generously ornamented kiritamukuta (conical crown), karna-kundala (ear ornament), mouktikmala (pearl neck ornament), an embellished vaijayantimala (a long garland-like neck ornament), ornate skanda aabhushana (shoulder ornament), bajubanda (an armlet, to be worn over upper portion of an arm), keyura (bracelet), mudrika (ring), an opulent yajnopavita(a cross belt over chest which has religious and social significance), udarabanda (waist band), minutely carved mekhala (waist ornament to be worn over lower garment), a tasselled nupura (ornament worn over ankle), and nuparapadika (ornament worn over the feet). (Fig. 3) Even the attendants on the outer walls are carved with ornaments which rival the ornaments of the deities. The chlorite schist used in the construction of the temple was instrumental in shaping the Hoysala style of temple architecture. It aids in such minute ornamentation, as it is softer while carving and gets hardened with exposure: ‘The Chalukya/Hoysala builders resorted to a stone of much finer grain—greenish or bluish-black chloritic schist. The latter is a close-textured stone, very tractable under the chisel and specifically suited to the preparation of minute carving which became a pronounced characteristic of the later style.’[7]

Unfinished Works in the Temple

Apart from studying the distinguishable changes in style of carvings, the process of carving can also be read from the unfinished images and friezes at the temple. The best case for observation is present on the north side of the circumambulatory path of the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple which displays an unfinished image. Judging from its place in the iconographic scheme of the temple as well as its pedestal which displays Lord Vishnu’s vahana (mount), Garuda, it is safe to assume that the unfinished image was of Vishnu. (Fig. 4)

The adhisthana (moulded basement) layers in the circumambulatory path of the temple help us speculate how the sculpting process might have taken place. There are six layers carved on the adhisthana, some layers are complete while others are in various phases of carving. One unfinished layer which the sculptors did not carve could possibly be the mythological layer, which is a standard layer in most Hoysala temples but is absent here.

The sculptural activity in the Hoysala reign proves to be extremely mature based on their temple building activity, mostly evident from the developed and intricate style. This advancement proves the prosperity of artistic community of that period from various signs of elaborate workshops of many artists. Moreover, they have immortalised themselves while remarkably doing their work at the same time.

[1] University of Mysore, Annual Report of Mysore Archaeological Department, 1933, 53.

[2] Collyer, The Hoysala Artists: Their Identity and Styles, 77.

[3] University of Mysore, Annual Report of Mysore Archaeological Department, 1933, 55.

[4] Acharya, Architecture of Manasara, 280.

[5] Bhattacharya, The Canons of Indian Art or A Study on Vastuvidya, 392.

[6] Collyer, The Hoysala Artists: Their Identity and Styles, 43.

[7] Brown, Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu), 138.

Bibliography

Acharya P.K. Architecture of Manasara. London: Oxford University Press, 1933.

Bhattacharyya, Tarapada. The Canons of Indian Art or A Study on Vastuvidya. Culcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 1963.

Brown, Percy. Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu). Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1971.

Collyer, Kelleson. The Hoysala Artists: Their Identity and Styles. Mysore: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, 1990.

Deglurkar G.B. विष्णुमूर्ते नमस्तुभ्यम्. Snehal Prakashan, Pune, 2013.

Deva, Krishna. Temples of India: Vol. I and II. New Delhi: Aryan Book International, 1995.

Dhaky, M. A., and Michael Meister, ed. ‘South India: Upper Dravidadesha later phase: AD 973-1336, Vol. I, Part III, Text.’ In Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1996.

Fergusson, J., and M. Taylor. Architecture in Dharwar and Mysore. J. Murrey, 1866.

Foekema, Gerard. Hoysala Architecture: Medieval Temples of Southern Karnataka built during Hoysala Rule. New Delhi: Books and Books, 1994.

———. A Complete Guide to Hoysala Temples. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1996.

Gupte, R.S. Iconography of Hindus, Buddhists and Jains. Mumbai: D.B. Tarporevala Sons and Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1972.

Hardy, Adam. Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation. New Delhi: IGNCA Abhinav Publications, 1995.

Nangia, Renupum. ‘Iconography of Hoysala period Temples.’ Unpublished PhD. thesis, Savitribai Phule Pune University, 1985.

Rice, B. Lewis, Mysore, Archaeological Department. Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. V. Part I. Mangalore: Basel Mission Press, 1902.

Ramchandra Rao, S.K. Pratima Kosha- Encyclopaedia of Indian Iconography. Bangalore: Kalpataru Research Academy, 1998.

Rao, T.A.G. Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol. I and II. Madras: The Law Printing House, 1916.

University of Mysore. Annual Report of Mysore Archaeological Department, 1933. Bangalore: The Superintendent at the Government Press, 1936.