The Lakshmi-Narasimha temple is a trikuta shrine (a shrine containing three garbhagrihas or sanctum sanctorums) located in Harnahalli village of Hassan district and is 35 km from Hassan, a city in Karnataka. The temple showcases a rich iconographic scheme wherein the influence of Vaishnavism is heavily emphasised. Various forms of Vishnu are carved on various parts of the east-facing temple of nirandhara type (sanctum without circumambulatory path inside the temple), enshrining the three forms of god, Keshava, Lakshmi-Narasimha and Venugopala, in its three garbhagrihas. The central garbhagriha exhibits the first form of the chaturvimshati murtis (twenty-four forms) of Vishnu, Keshava. (Fig. 1) The left side of the central garbhagriha has a less ornate sanctum enshrining Lakshmi-Narasimha (Fig. 2), and the right side shows another similar shrine displaying Venugopala (Fig. 3). The temple stands on high pedestal and its outer wall is abundantly ornamented with various icons and decorative motifs; various tharas (ornamented layers) like creeper layer, elephant layer, horsemen layer, swan layer, etc., are crafted over the adhisthana (moulded basement of a temple), and the jangha (an elevation above adhisthana, wall frieze) is decorated with icons of various deities and their attendants.

Vaishnava philosopher Ramanuja’s theology, which was dominant in this region under Hoysala reign, also reflects on the iconographic scheme in the temples built by them. According to his theology, Para-Vasudeva is the transcendental being who controls the universe. Para-Vasudeva is conceived in a fivefold aspect in this doctrine: the highest form, Para-Vasudeva; emanatory forms, vyuha; incarnations, vibhava; inner controller among individual beings, antaryami; and iconic manifestation, archa. Out of these, vyuha, vibhava, and Para-Vasudeva make their appearance on the temple walls.

Some of the noteworthy sculptural art observed in the temple space is listed below.

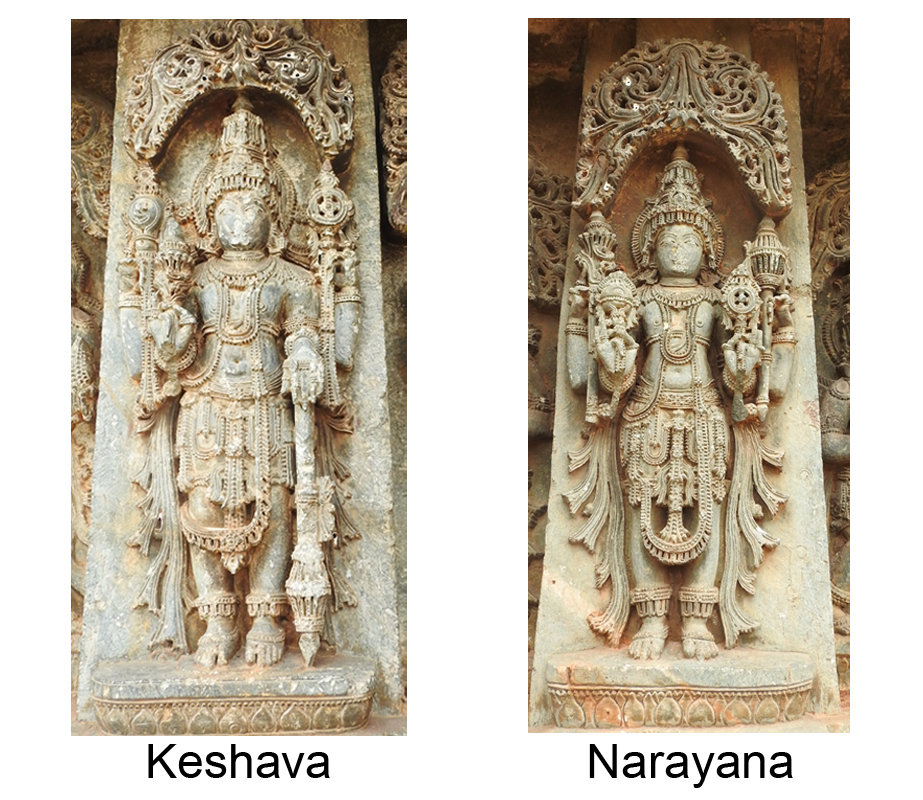

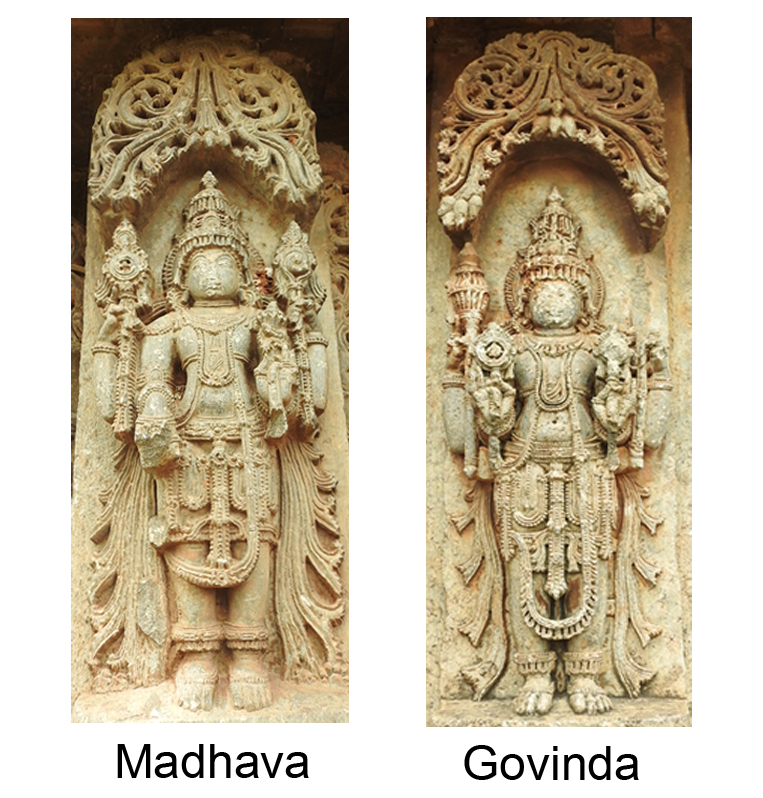

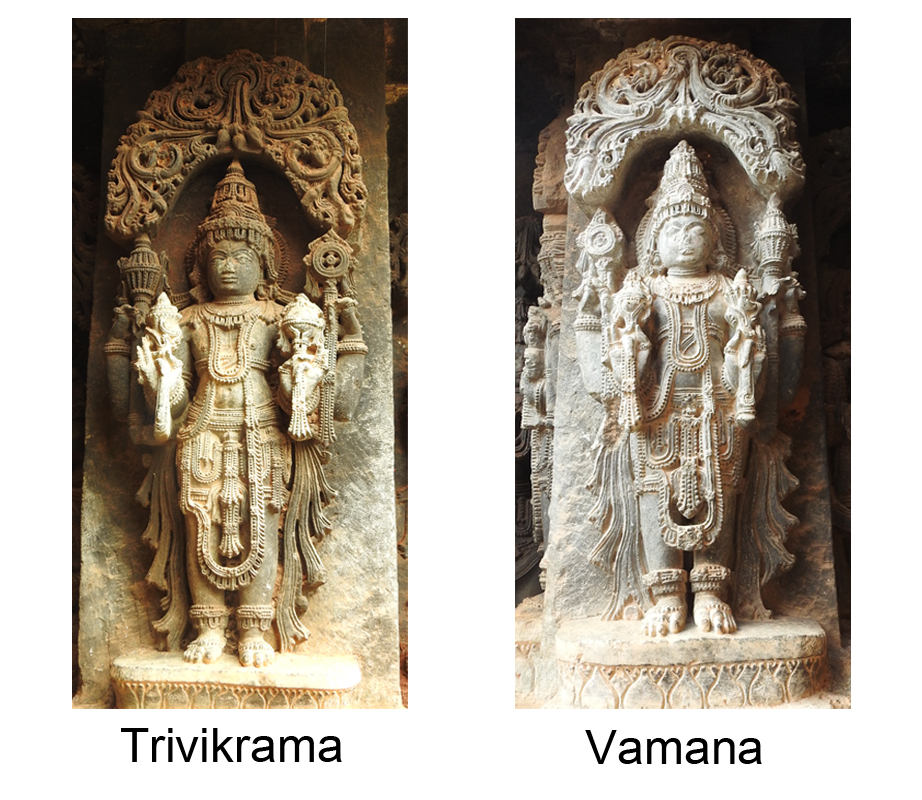

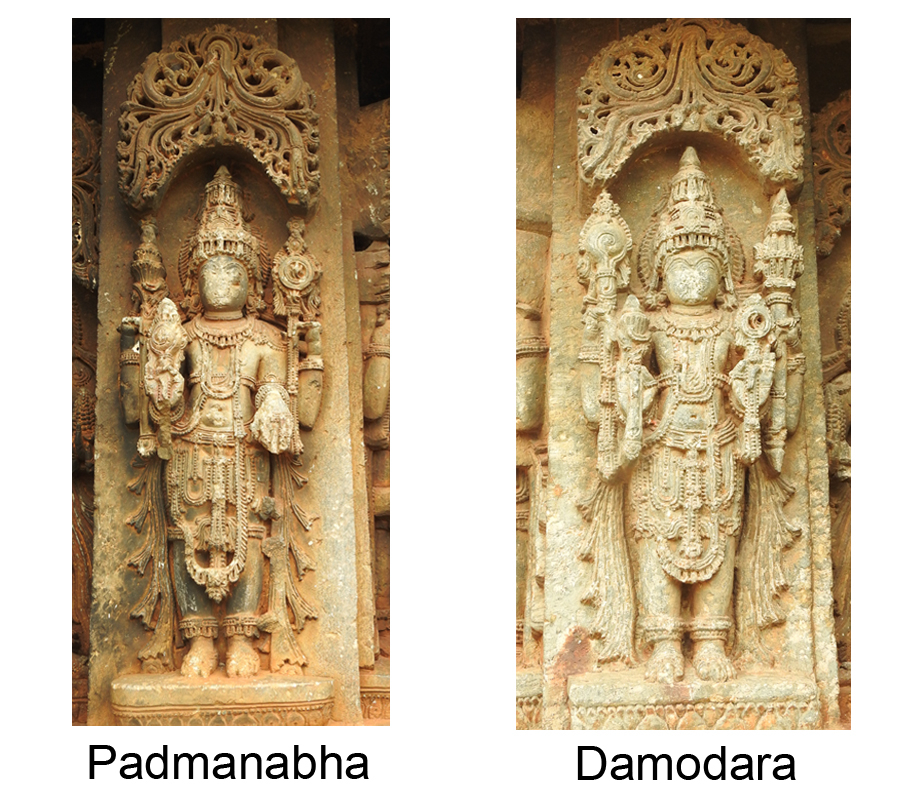

Chaturvimshati form of Vishnu

In Anushasanaparva of Mahabharata, Vishnu is praised with 1,000 names in the hymn, Vishnu Sahasranama. Out of those 1,000 names, 24 are deemed most significant and are called as chaturvimshati (24) forms of Vishnu, which are seen in sculptural form since sixth century CE. In the Hoysala period, possibly due to prominent Vaishnava movement in vogue in that region, these 24 forms were crafted on the walls, pillars, beams and ceilings at many principle Hoysala temples, and the shankha (conch), chakra (discus), gada (mace) and padma (lotus) were mandatory attributes which were seen with such icons. There are various theories in several Sanskrit works about the emergence of chaturvimshati murtis. For instance, from Ramanuja’s theology, the vyuhas are the chaturvimshati forms of Vishnu, which emanate from the principle form, Para-Vasudeva. On the other hand, the Ahirbudhnya Samhita states that Keshava, Narayana and Madhava are the forms of Vishnu which emanated from Para-Vasudeva.

The basic iconographic norm while carving these icons states that all 24 forms should be uniform, except for their attributes such as shankha, chakra, gada and padma. When they are carved in standing position, they should be in samapada (erect standing posture) posture with four hands and principle ornaments. As they are identical in nature, they are distinguished from one another by differentiating their attributes. There is a specific order that defines which attribute should be carved in which hand; for example, the first form, Keshava, should hold padma in his lower-right hand, shankha in his upper-right hand, chakra in his upper-left hand and gada in his lower-left hand. These 24 forms were elaborately discussed in scriptures like Agnipurana, Padmapurana, Skandapurana, Abhilashitartha Chintamani, Chaturvarga Chintamani, Rupamandana and Dharmasindhu which contain the order of attributes, according to particular forms of Vishnu. In addition, the 24 forms are accompanied by their respective consorts; forms like Purushottama, Adhokshaja, Narasimha, Achyuta, Upendra, Janardana, Hari and Krishna also have depictions of Sridevi and Bhudevi on their pedestals. The following table gives the details about the 24 forms displayed on the jangha of the temple along with their consorts. (Figs 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9)

|

Name of Vishnu |

Order of Attributes (in clockwise manner starting from lower-right hand and ending at lower-left hand) |

Consort[1] |

|

Keshava |

padma, shankha, chakra and gada |

Kirti |

|

Narayana |

shankha, padma, gada and chakra |

Kanti |

|

Madhava |

gada, chakra, shankha and padma |

Tushti |

|

Govinda |

chakra, gada, padma and shankha |

Pushti |

|

Vishnu |

gada, padma, shankha and chakra |

Driti |

|

Madhusudana |

chakra, shankha, padma and gada |

Shanti |

|

Trivikrama |

padma, gada, chakra and shankha |

Kriya |

|

Vamana |

shankha, chakra, gada and padma |

Daya |

|

Shridhara |

padma, chakra, gada and shankha |

Medha |

|

Hrishikesha |

gada, chakra, padma and shankha |

Harsha |

|

Padmanabha |

shankha, padma, chakra and gada |

Shraddha |

|

Damodara |

padma, shankha, gada and chakra |

Lajja |

|

Sankarshana |

gada, shankha, padma and chakra |

Saraswati |

|

Vasudeva |

gada, shankha, chakra and padma |

Lakshmi |

|

Pradyumna |

chakra, shankha, gada and padma |

Priti |

|

Aniruddha |

chakra, gada, shankha and padma |

Rati |

|

Purushottama |

chakra, padma, shankha and gada |

Vasudha |

|

Adhokshaja |

padma, gada, shankha and chakra |

Shubha |

|

Narasimha |

chakra, padma, gada and shankha |

Vidhula |

|

Achyuta |

gada, padma, chakra and shankha |

Sukha |

|

Upendra |

padma, chakra, shankha and gada |

Sundari |

|

Janardana |

shankha, gada, chakra and padma |

Uma |

|

Hari |

shankha, chakra, padma and gada |

Shuddhi |

|

Krishna |

shankha, gada, padma and chakra |

Buddhi |

- Adi Murti (Para-Vasudeva): According to Ramanuja’s theology, Para-Vasudeva is a term for the transcendental Godhead abiding in the highest realm known as Vaikuntha. In the five-fold aspect of this doctrine, Para-Vasudeva is the highest form of Vishnu; he is complete with all six attributes in their entirety, jnana (wisdom), aishvarya (sovereignty), shakti (energy), bala (strength), virya (valour), and tejas (lustre). Vishnu is an all-pervasive divine form and is the primal source of all other divine forms and manifestations.[2] In sculptural form, Vishnu is shown with four arms, and seating on Sheshanaga (serpent), also known as Ananta, who symbolises primordial principle of time and is intimately associated with Lakshmi. In this form, Vishnu is seated on the coils of Ananta, in a relaxed manner with his left leg folded over the coils and right leg resting down. His upper two hands hold shankha and chakra while his lower-right hand is placed on the coils and lower-left hand rests on the left knee. The five hoods of Ananta serve as a parasol over his head. (Fig. 10)

Varaha

Varaha is the third avatar of Vishnu who recovers Bhudevi (the Earth Goddess) from the depths of the ocean. He is sculpted over the jangha and shikhara (tower, spire, crowning dome) of the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple three times.

In the elaborate panel illustrating the Bhuvaraha (Bhudevi and Varaha) episode on the jangha in the south side of the temple, the demon Hiranyaksha is seen approaching Bhudevi with sword and shield; subsequently, Varaha is shown lifting Bhudevi with his tusks to save her as he tramples Hiranyaksha, and the goddess is shown embracing the Varaha. Bhuvaraha was sculpted with six hands originally, but currently many of those hands are broken, and from the remnants of those hands, only upper part of gada, a weathered chakra and a shankha can be observed. (Fig. 11) The back wall of the Lakshmi-Narasimha shrine on the jangha exhibits a seated image of Lakshmi-Varaha accompanied by attendants. Varaha is seated in vama-lalitasana (sitting on a high pedestal with the right leg hanging and the left leg folded up) on a throne, and Lakshmi is perched on his folded left leg, embracing him with her right hand while holding a padma in her left hand. Varaha is bedecked in a multitude of ornaments and he is holding shankha, chakra, gada and padma while embracing his consort, Lakshmi.

A third depiction of Varaha can be seen on a north side of the shikhara of the central garbhagriha, where he sits in sukhasana (sitting in relaxed manner) while Garuda, a vahana (mount or vehicle) of Vishnu, is seen in a panel below him. Varaha is carved with six hands; he holds his primary attributes shankha, chakra, gada and padma in his four hands while his lower right hand rests on the pedestal and his lower left hand is placed on his left knee.

Narasimha

According to scriptures, Narasimha is the fourth incarnation of Vishnu who comes to the rescue of his devotee in the form of an anthropomorphic lion and kills the demon Hiranyakashapa. Among the Vaishnava imageries present in the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple, the Narasimha avatar of Vishnu appears to be a favourite as it is carved seven times in various places in the temple premises.

- Garbhagriha: The Lakshmi-Narasimha form is enshrined in the left garbhagriha of the temple. Narasimha is bedecked abundantly in ornaments and is seen with his principle ayudhas (weapons)—shankha, chakra, gada and padma, and a well-ornamented Lakshmi is seen sitting on his left leg. The 10 avatars of Vishnu—Mastya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parashu Rama, Dasharathi Rama, Krishna, Buddha and Kalki—are carved on the parikara (an arch behind an icon depicting varied imagery, mostly related to the icon) behind him. On the lalatabimba (central symbol on door lintel) of the garbhagriha, Lakshmi-Narasimha is again carved with various attendants, devotees, Garuda and Pralhada (devotee of Vishnu and son of Hiranyakashyapa who was slayed by Narasimha). Here, Narasimha is sitting in vama-lalitasana, holding shankha, chakra, gada and padma, with Lakshmi sitting on his left leg holding bijapuraka (citron, symbolised as ‘seed of universe’).

- Jangha: At the jangha of the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple, Narasimha is shown four times in various forms. In the chaturvimsati form, Narasimha is in sthanaka (standing) posture holding his four principle ayudhas, with small figures of Sridevi near his right leg and Bhudevi near his left leg, and Garuda carved on his pedestal. The entire story of Narasimha avatar is also seen in the Vidaraka (fierce) Narasimha panel. (Fig. 12) The demon king Hiranyakashyapa was a steadfast devotee of Shiva, while his son Pralhada had an unwavering devotion towards Vishnu. Hiranyakashyapa tried to convert his son’s devotion from Vishnu to Shiva through various means, some of which were rather brutal. But Pralhada’s resolute faith that Vishnu is everywhere did not waver and, hence, to prove his son wrong, Hiranyakashyapa kicked a pillar from which Narasimha materialised. Hiranyakashyapa was bestowed with a boon by Shiva stating he cannot be killed with any weapon by a man or an animal, during day or night, inside or outside a house, on the land or the sky; thus, Narasimha with the body of a man and the head of a lion, killed him on his lap with his claws at dusk at the threshold of his house. At the temple, the panel showing this story starts from the left side, where Hiranyakashyapa is shown approaching with shield and sword and in next sculpture, Vidaraka Narasimha is carved sitting in savya-lalitasana (sitting on a high pedestal with left leg hanging down and right leg folded up), with Hiranyakashyapa splayed on his lap and Narasimha ripping open his stomach with his claws. In the carving, Narasimha has a scowl; he is shown with eight hands wherein his lower two hands hold Hiranyakashyapa’s head and leg and upper two hands hold shankha and chakra, with his two other hands he tears open the stomach while his remaining hands are busy drawing out the intestines from the corpse. On his right side, Pralhada is seen standing in anjalimudra (hand pose suggesting submission or prayer) facing the Narasimha. The Lakshmi-Narasimha form is carved on the jangha on the north side of the garbhagriha on the left. The ornamentation and attributes are similar to the image of Lakshmi-Narasimha from the grabhagriha; in addition, attendants flank both sides of Lakshmi-Narasimha image. Although the sculpture is a little weathered, the calmness in the features of otherwise fierce Narasimha is visible here. His fourth appearance comes in Yoga-Narasimha form. Here, he is sculpted gracefully showing the benign aspect of Narasimha, where he is in sitting in asana wearing yogapatta (scarf tied around knees to assist in the practice of yoga), his upper two hands hold ayudhas, shankha and chakra, and his lower two hands rest on his knees.

- Shikhara: On the shikhara of the temple, Yoga-Narasimha in sitting posture wearing yogapatta has been carved on the panel where he is shown with his ayudhas and his lower two hands on his knees.

Trivikrama

Trivikrama is fifth incarnation of Vishnu who in his gigantic form covers three worlds on three strides; Trivikrama is related to Vishnu’s Vamana (person with dwarfism) avatar. As per the legends narrated in Ramayana, Matsyapurana, Agnipurana, and Padmapurana, demon king Bali defeated Indra, the king of gods, and claimed his throne. Vishnu took the form of Vamana and went to Bali with the intent of ensuring Indra’s sovereignty again. He extracted a promise from Bali while he was performing ashvamedha (horse sacrifice), according to which Bali was to provide a piece of land which Vamana could cover in three strides. Once the boon was granted, Vamana assumed Trivikrama form and covered the entire earth in one step, the mid region between earth and heaven in second step, and as there was no place for the third step, Bali offered his head. Trivikrama put his third foot on Bali’s head and pushed him into pataala (nether region below the surface of earth, residence of the demons) which subsequently reinstated Indra on his throne.

The legend of Trivikrama is carved on the walls of the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple where Bali is shown pouring water from kamandalu (water pot), symbolising the bestowal of a boon to Vamana, who is shown with his principle attribute, chhatra (umbrella). In the next sculpture to the right, Trivikrama is shown with his principle attributes, padma, gada, chakra and shankha and his right foot suspended in the air up till his chest, symbolising his second step to cover the mid region between earth and heaven; Garuda is seen in anjalimudra below the pedestal.

The Trivikrama form is also found in the chaturvimshati murtis of Vishnu, where his iconography is different. On the jangha, Trivikrama is shown standing in samabhanga (erect standing posture) with similar order of attribute, i.e., padma, gada, chakra and shankha as shown in Trivikrama panel.

Hayagriva

Hayagriva is one of the minor avatars of Vishnu. According to Devi Bhagavata, a demon named Hayagriva was bestowed with a boon that he will not be defeated by a man or a beast, because of which he started troubling the gods. The gods went to Devi (the Mother Goddess) for aid, who directed them to Vishnu. Vishnu incarnated on earth with the face of a horse and the body of a man, and, because of his features, also came to be known as Hayagriva (haya-horse, griva-neck). According to a legend associated with this Vishnu avatar, the Vishnu Hayagriva goes on to defeat the demon Hayagriva.

Another legend which is mentioned in Skandapurana and Shantiparva in Mahabharata talks about Hayagriva as a rescuer of the Vedas and knowledge. The story goes that two demons, Madhu and Kaitabha, stole the vedas, and Brahma asked Vishnu for aid in retrieving the holy texts, because of which Vishnu incarnated as Hayagriva to fight Madhu and Kaitabha. Hayagriva distracted the demons, retrieved the vedas and handed them to Bramha. Therefore, in some instances, Hayagriva is carved with the principle attributes of Vishnu as well as the personified forms of the four vedas. Like Saraswati, Hayagriva is also looked upon as the god of learning. The image of the four-handed Hayagriva is carved on the south shikhara of the temple. He is seen in fighting posture with the principle attributes of Vishnu, shankha, chakra, gada and padma. With kiritamukuta (conical crown) on his head and bedecked with ornaments, Hayagriva is shown trampling over a demon as another one approaches him with a sword.

Venugopala

The Venugopala avatar of Vishnu represents the early life of Krishna in Vrindavana. It is carved at various places in the temple, including the garbhagriha, jangha and shikhara. Venugopala is enshrined in the right garbhagriha with Garuda carved on his pedestal, and the image is accompanied by cattle and cowherds. He stands with his right leg bent in front of his left leg, and is holding a flute with his hands on the right side. On the jangha, Krishna is standing under kadamba tree, surrounded by cowherds and damsels, and Garuda is carved on the pedestal in anjalimudra. On the front side of the shikhara of the mukhamandapa (an entrance hall), Venugopala is placed with iconography similar to his image at the garbhagriha.

Govardhanadhari Krishna

The story of Govardhanadhari (one who lifted Govardhana mountain) Krishna is narrated in the Vishnuparva of Harivamshapurana. According to the text, Krishna persuaded the Vrindavan dwellers to abandon the worship of Indra for rains in favour of giriyajna (the worship of mountain Govardhana), as Govardhana was responsible for rains and in turn a good harvest. This angered Indra and he flooded Vrindavan. Krishna lifted Govardhana to protect the villagers from flood and all the villagers took refuge under it. This supernatural feat of Krishna compelled Indra to see Krishna’s divinity and ask for forgiveness for his arrogance.

There are two beautiful representations of Govardhanadhari Krishna on the jangha of the temple, both carved in elaborate perfection to incorporate the minute details of this episode. They show Krishna standing and holding aloft the mountain with his left hand while he is surrounded by villagers. (Fig. 13)

Kaliyamardana

Kaliyamardana (where Krishna defeats serpent Kaliya) is an episode from the younger days of Lord Krishna when he was living with his foster parents, Nanda and Yashoda. This story appears in Chapter 12 of Vishnuparva in Harivamshapurana; it shows the divine aspect of Krishna where as a child, he defeats the gigantic poisonous serpent, Kaliya. The story goes that river Yamuna was being infected by the poison spewed from Kaliya, which caused sufferings to the residents of Vraj, where Krishna was residing. To end this torment, Krishna jumped into the waters and overpowered Kaliya. Krishna jumped on to the central hood of the five-hooded Kaliya and started dancing, causing the serpent great pain. Kaliya accepted defeat and on Krishna’s orders went to reside in the river with his family. This was an important episode in Krishna’s life that established his divinity.

Kaliyamardana is carved multiple times in the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple. On the jangha of the temple, Krishna is seen dancing on the middle hood of the five-hooded serpent, Kaliya, while holding the tail in his hand; Garuda and Kaliya’s wives are seen below in anjalimudra. (Fig. 14) The detailing is magnificent, evident from the river sculpted on the pedestal with riverine creatures like fishes and turtles inside the waters. Another depiction is present on the ceiling of the mukhamandapa (an entrance hall) which has been carved exquisitely in a narrow space.

Lakshmi-Narayana

The image of Lakshmi-Narayana appears twice on the jangha of the Lakshmi-Narasimha temple. A panel carved in the north side of the pradakshinapatha (circumambulatory path) shows Garuda in anjalimudra on the left side of the throne while another similar panel is carved in the south side of the pradakshinapatha with a water pot near the throne in place of Garuda. Lakshmi and Narayana are seen seated on a throne, with Lakshmi sitting on the left leg of Vishnu, holding the padma in her left hand and embracing Vishnu with her right hand. Vishnu is seated in vama-lalitasana carved with his principle attributes, embracing Lakshmi, and they are both bedecked with abundant ornaments. The whole panel is carved over padmasana (lotus seat) and the deities are accompanied by attendants.

Hanuman

Hanuman is one of the most significant characters in Vaishnavism. He is identified as a staunch devotee of Dasharathi Rama, a principle incarnation of Vishnu. As the customary iconographic norm for depicting Hanuman, he is depicted with as an anthropomorphic monkey figure on the jangha of the temple; his right hand is lifted up over his head in chapetadana-mudra (hand gesture of slapping), and is adorned with minimalistic ornaments wearing only keyura (bracelet), bajubanda (ornament worn on arm) and nupura (ornament worn over the ankle) made of rudraksha (a sacred seed in Hinduism) beads and a sparse adhovastra (waistcloth) with a simple yajnopavita (a cross belt over chest, sacred thread).

The strong hold of Vaishnavism throughout the Hoysala rule is evident from various temples built by them. This temple is no exception as it richly constitutes imagery related to Vaishnavism. As mentioned earlier, the rulers seem to be advocates of pancharatra doctrine propagated by Ramanuja, because they have dedicated the central shrine to the first form, Keshava of vyuhantara (emanatory forms) doctrine from Ramanujan’s theology. The other aspect of this theology, Para-Vasudeva or Adi murti is also seen here. The influence of Vaishnavism is also emphasised through the copious depictions of Lord Vishnu’s life, including the depiction of episodes from his childhood, his various incarnations and the chaturvimshati forms. The temple is filled with carvings like the Kaliyamardana scene, which is sculpted on the middle beam of the ceiling of mukhamandapa, illustrating optimum utilisation of space. All this show clever tactics of patrons to imbibe the supremacy of Vaishnavism and propagate the religion further through the use of the temple building activity.

[1] Deglurkar, विष्णुमूर्ते नमस्तुभ्यम्, 113.

Acharya P.K. Architecture of Manasara. London: Oxford University Press, 1933.

Bhattacharyya, Tarapada. The Canons of Indian Art or A Study on Vastuvidya. Culcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 1963.

Brown, Percy. Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu). Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1971.

Collyer, Kelleson. The Hoysala Artists: Their Identity and Styles. Mysore: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, 1990.

Deglurkar G.B. विष्णुमूर्ते नमस्तुभ्यम्. Pune: Snehal Prakashan, 2013.

Deva, Krishna. Temples of India: Vol. I and II. New Delhi: Aryan Book International, 1995.

Dhaky, M. A., and Michael Meister, ed. ‘South India: Upper Dravidadesha later phase: AD 973-1336, Vol.I, Part III, Text.’ In Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1996.

Fergusson, J., and M. Taylor. Architecture in Dharwar and Mysore. J. Murrey, 1866.

Foekema, Gerard. Hoysala Architecture: Medieval Temples of Southern Karnataka built during Hoysala Rule. New Delhi: Books and Books, 1994.

———. A Complete Guide to Hoysala Temples. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1996.

Gupte, R.S. Iconography of Hindus, Buddhists and Jains. Mumbai: D.B. Tarporevala Sons and Co. Pvt. Ltd., 1972.

Hardy, Adam. Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation. New Delhi: IGNCA Abhinav Publications, 1995.

Nangia, Renupum. ‘Iconography of Hoysala period Temples.’ Unpublished PhD. thesis, Savitribai Phule Pune University, 1985.

Rice, B. Lewis, Mysore, Archaeological Department. Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. V. Part I. Mangalore: Basel Mission Press, 1902.

Ramchandra Rao, S.K. Pratima Kosha- Encyclopaedia of Indian Iconography. Bangalore: Kalpataru Research Academy, 1998.

Rao, T.A.G. Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol. I and II. Madras: The Law Printing House, 1916.

University of Mysore. Annual Report of Mysore Archaeological Department, 1933. Bangalore: The Superintendent at the Government Press, 1936.