The early western Calukyas emerged on the historical canvas of the Deccan region of peninsular India in the second half of the 6th century. The heartland of the Calukyas lay close to the Malprabhā river valley in the modern-day Bagalkot district of Karnataka. The twin cities of Bādāmi and Aihoḷe, and the site of Paṭṭaḍakal, formed the nucleus of Calukya power. While Bādāmi served as the capital city, then known as Vātāpi, Aihoḷe was an important population centre and home of a famous mercantile guild known as the ‘Ayyavole 500’. Paṭṭaḍakal, unlike Bādāmi and Aihoḷe, never had a sizeable population; however, it functioned as a royal commemorative site during the early Calukya period. These sites of political power and economic resources became centres of artistic patronage, which is attested by a plethora of highly embellished rock-cut shrines and structural temples found there. During their long reign of over 200 years (c. 540‒757 AD), the early Calukyas not only achieved political unification of much of the Deccan but also helped ensue a glorious era in the field of art and architecture. The religious monuments of the early Calukyas, built in stone, form the largest surviving body of early Deccan architecture. The corpus of stone temples and the associated sculptures provides an excellent guide to the religious milieu and the personal religious affiliation of the early Calukya rulers. This article undertakes a detailed analysis of the religious iconography of the early Calukya sculptures adorning the walls and ceilings of rock-cut caves and structural temples of Bādāmi, Aihoḷe and Paṭṭaḍakal. The aim is to highlight that the building of temples, which spanned nearly the entire period of the Calukya hegemony, was an act of religious piety for the rulers and at the same time a testimony of their political stature and legitimacy. An attempt is made to show how political power, religious piety and the patronage of Calukya rulers were intertwined and can be understood through the sculptural schema of their temples.

Architectural styles and influences

Early Calukya architecture is known for its unique intermingling of different construction techniques and distinctive architectural styles. The corpus of early Calukya temples includes both cave temples and free-standing temples, and monuments built in both techniques are found in Bādāmi and Aihoḷe. It is interesting to note that not only are these excavated cave temples and structural temples found beside each other in Bādāmi and Aihoḷe, but were also built in the same period. Possibly excavated during the second half of the 6th century, the cave temples of Bādāmi and Aihoḷe represent the pinnacle of rock-cut architecture of the Deccan.

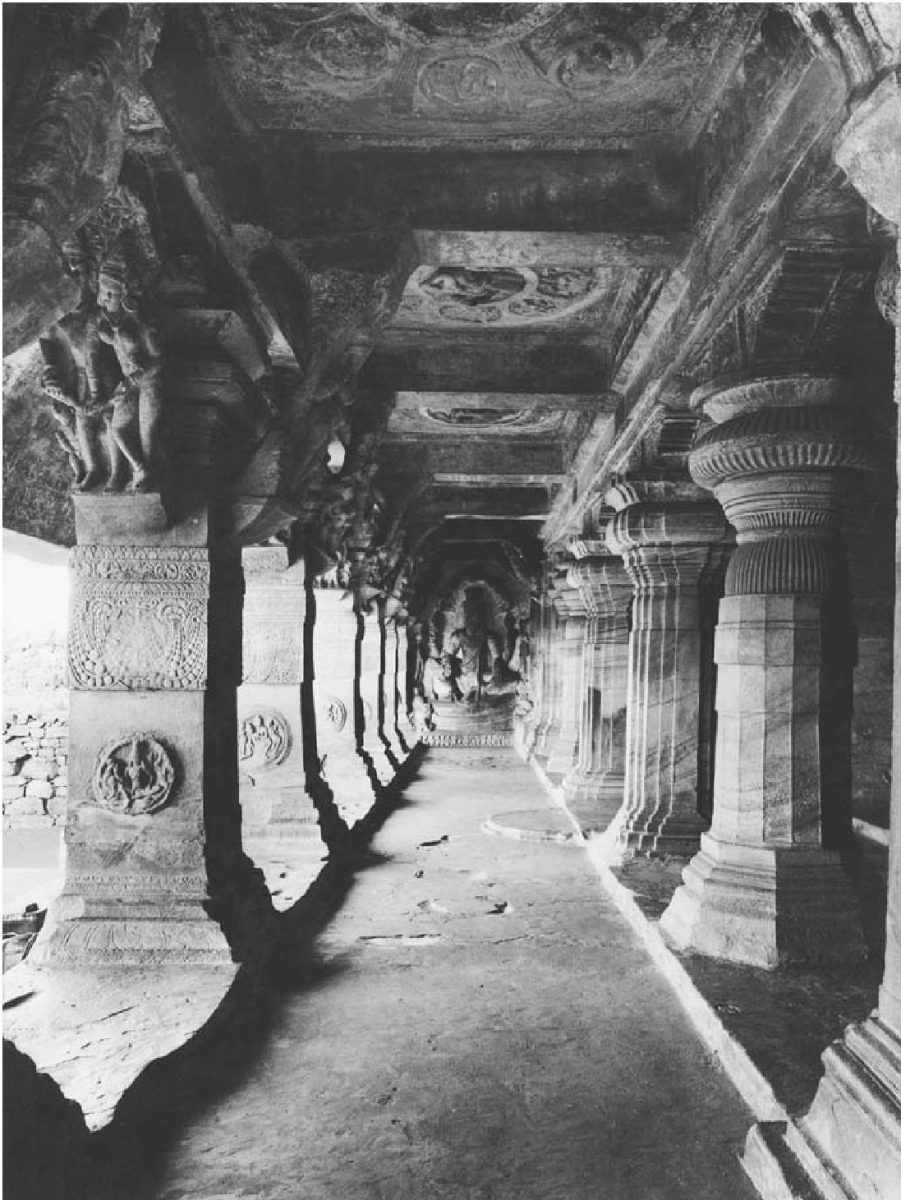

The largest and most impressive of the early Calukya cave is the Cave 3 at Bādāmi (Figure 1). It has a columned veranda with ornately carved square pillars, followed by an inner hall (maṇḍapa) disposed with rounded columns, and a small shrine containing a pedestal cut into the rear wall. The arrangement of pillars, architectural decoration, and sculptural programme of the early Calukya caves shows strong artistic ties with earlier caves of the Deccan such as the ones at Ajanta, Elephanta and Ellora in Maharashtra. George Michell argues that the guilds who had worked at Ajanta, Elephanta and Ellora migrated to the Bādāmi region once the early Calukyas established themselves as active patrons (Michell 2014:17).

In terms of architectural idiom, early Calukya temples register a remarkable assemblage of Drāviḍa and Nāgara styles. The landscape of Paṭṭaḍakal is marked by temples built in contrasting Drāviḍa and Nāgara idioms. While the Sangameśvara, Mallikārjuna and Virūpākṣa temples sport a multi-storeyed pyramidal superstructure, the Kadasiddheśvara, Jambuliṅga, Galaganātha and Kāśiviśveśvara temples found in the same complex are crowned with northern style curvilinear śikhara (crowning cupola). In some temples such as the Pāpanātha temple at Paṭṭaḍakal and Durgā temple at Aihoḷe, attributes of both Drāviḍa and Nāgara traditions intermingle to form a unique early Calukyan architectural style.

This unique fusion of artistic traditions can perhaps be explained by the strategic geographical location of early Calukyas in the Deccan (Meister 1986:7; Michell 2014:17), which is a luminal space between northern and southern India and, therefore, receptive to influences from both sides. These artistic influences can also be credited to the political associations and struggles for power with kingdoms in both north and south. In the reign of over two centuries, Calukyas faced political challenges from Harṣavardhana in the north and the mighty Pallavas in the south. An inscription dated to 634‒35 CE on the eastern wall of the Meguti temple at Aihoḷe records the victory of Pulakeśi II over Harṣavardhana and his feudatories (Padigar 2010:22). However, Calukyas faced an incessant aggression from the Pallavas in the south, which resulted in temporary loss of their supreme authority between 642 and 654 CE. The unity and strength of the Calukyas was restored after 13 years by Vikramāditya I. The vitality and slenderness associated with the Pallava sculptural idiom is found in many figures of Paṭṭaḍakal temples, especially those showing Śiva in various guises.

A direct link with the Pallava artistic style is seen in the portrayal of Durgā as a buffalo demon slayer (Mahiṣāsurmardini) in which the demon Mahiṣā, similar to the cave temples of Māmallapuram in Tamil Nadu, is represented in human form, recoiling in fear. According to Michell (2014:28), the reason behind such iconographic parallels can be the three military expeditions of Vikramāditya II to the Pallava territories during which he brought Pallava artists back to the early Calukya homeland.

Besides that, an inscription engraved on the Kailāśanātha temple at the Pallava capital records how impressed Vikramāditya II was with the sight of the Kailāshnātha temple that he declined to desecrate it or even plunder its treasures. It is even claimed by some scholars that the Virūpākṣa temple built during his reign by his senior queen, Lokamahādevī, to commemorate his victory over Pallavas at Paṭṭaḍakal was modelled after the same Kailāśanātha temple. It suffices to conclude that the power struggles of the Calukya period inspired their architectural styles to adopt and adapt different artistic traditions. However, even if early Calukya architecture combined features of other traditions, it was marked by great distinctiveness and individuality.

Religious milieu and iconographic programme

The sacred landscape of the early Calukya era was shared by all the major established religions such as Vaiṣṇavism, Śaivism, Jainism and Buddhism. Besides that, some local cults related to fertility and serpent worship also formed part of the religious milieu of the time. In a way, there was an eclectic mix of religious belief systems prevalent during the reign of the Calukyas. This eclectic mix of religious beliefs and practices is best represented by the cave temples of Bādāmi. The architectural programme of the early Calukya era starts with the four cave temples excavated into the red sandstone bluffs located overlooking an artificial lake. Out of the four, two cave temples are consecrated to Viṣṇu, one to Śiva and the fourth is dedicated to Jains. This syncretism of religions is replicated within the sculptural programme of the cave temples as well.

The best example of which is the visual representation of Viṣṇu and Śiva in the same image as Hari-Hara (Figure 5). The earliest sculptural representation of Hari-Hara is found in the Bādāmi caves. Śiva forms the right side of this deity and is shown holding a battleaxe entwined with a snake whereas Viṣṇu on the left is shown holding a conch shell.

Fig. 5: Hari-Hara, Cave 3, Bādāmi

The religious preferences of the early Calukya kings are evident from inscriptions and, of course, reflected in the dedications of their temples. In their early inscriptions, Calukyas claimed to be Vaiṣṇavas. In an inscription of 578 CE (Padigar 2010:9) found in Cave 3 of Bādāmi, Maṅgaleśa is described as Parama-Bhāgvata, i.e., a great devotee of Viṣṇu. Similarly, his successor Pulakeśi II is also called Parama-Bhāgvatain his Chipḷun copper plates (Padigar 2010:42). The Vaiṣṇava caves of Bādāmi contain impressive bar-reliefs sculptures of the various Viṣṇu incarnations such as Varāha (boar), Narasiṁha (lion), and Vāmana (dwarf).

The most spectacular of these is the huge sculpture of Viṣṇu as Vaikunṭha, seated on Śeṣa. The figure is four-armed and seated with royal ease and shown in a full, fleshy form, which is associated with western Deccan style (Huntington 1993:288), but wears an unusual headdress, which may be an early Calukyan characteristic, possibly with some southern associations. Apart from the two Vaiṣṇava cave temples, the so-called Upper Śivālaya, located on the highest spur of the northern hill of Bādāmi, was also perhaps dedicated to Viṣṇu. It is argued by many scholars (Meister 1986:24) that neither the present sanctum pedestal nor the popular name of the temple accurately reveals its original dedication.

The iconographic programme of the temple that unfolds in the niches of its outer walls includes panels depicting Kṛṣṇa lifting the mount Govardhana (south), Kṛṣṇa trampling the serpent Kālīya (west), and Narasiṁha eviscerating Hiraṇyakaśipu (north) clearly indicates its Vaiṣṇava affiliation.

Fig. 7 and 8: Kṛṣṇa as Govardhanadhara, west wall, Upper Śivalaya, Bādāmi; Narasiṁha, north wall, Upper Śivalaya, Bādāmi

It shall not be presumed that the early Calukya kings of Vaiṣṇava affiliation only patronised Viṣṇu temples. As a tool to legitimize their political power, early Calukya rulers tapped the above-mentioned religious diversity of the time and tolerated and patronised temples dedicated to Śiva, Buddha and Jina. In contrast to Cave 3 depicting avatāras (forms) of Viṣṇu, cult affiliation of Cave 1 at Bādāmi is realized through the eighteen-armed Naṭarāja carved at the entrance.

Fig. 9: Śiva Naṭarāja, right wall, facade of Cave 1, Bādāmi

The harmonious array of god-hands holds weapons such as an axe and trident, a drum, and a sinuous snake while the other hands are arranged in graceful dance postures. The cave also portrays syncretic images of Hari-Hara and Ardhanāriśvara (Śiva joined with Pārvati in a single image) facing each other from either end of the verandah. Cave 4, on the other hand, is a Jain cave and houses a majestic cult icon of Mahāvīra carved from the rear wall of the sanctum. The most striking feature of the cave is the carved wall panels of Pārśvanātha and Bāhubali. However, from the mid-7th century, there seemed to be a socio-religious change from such religious tolerance to sectarian predominance of Śaivism.

This change came in the later part of the Calukya reign when Vikramāditya I became a personal devotee of Śiva after he underwent the initiation ceremony of Śivamaṇḍala-dīkṣāin 659 CE. Thereafter, the epithets of Calukya kings changed to Parama-Maheśvara, i.e., a great devotee of Maheśvara. The temples of Paṭṭaḍakal, which represent the climactic phase of Calukya architecture and patronage, are predominantly Śaiva by dedication. The three magnificent temples at Paṭṭaḍakal—Sangameśvara, Virūpākṣa and Mallijārjuna—show Śiva in different avatāras. The most common of which are those of Naṭarāja (Śiva as king of dance), Lakulīśa (naked form of Śiva holding the club), Bhikṣāṭanamūrti (Śiva as wandering ascetic), Bhairava (demonic form of Śiva), Liṅgodhava Śiva (Śiva appearing out of the flaming phallus (liṅga)), Hari-Hara, and Śiva with Pārvati and Nandi. Within in the broad range of Śaiva themes on Paṭṭaḍakal monuments, a few images of Viṣṇu are also incorporated. For instance, panels on the north wall of the Virūpākṣa temple portray the representation of Uma-Maheśa alongside an impressive image of Viṣṇu as Virātpuruṣa carrying an array of weapons.

This balance of Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava themes is a unique feature of early Calukya temples. The Mālegitti Śivālaya in Bādāmi has a pair of Śiva and Viṣṇu icons on the northern and southern niches of the maṇḍapa respectively. Similarly, the Durgā temple in Aihoḷe also accommodates a broad range of icons—Vṛṣvāhana (Śiva with Nandi), Narasiṁha, Viṣṇu with Garuḍa, Varāha and Mahiṣāsurmardini—to create a balance of Vaiṣṇava and Śaiva themes.

Early Calukya sculptures and political allegory

The personal religious affiliation of Calukya rulers shows a shift from Vaiṣṇavism to Śaivism. However, this shift does not obliterate the portrayal of Viṣṇu icons from the later temples. The balance of Vaiṣṇava and Śaiva themes seen throughout the Calukya architecture is indicative of the eclectic religious environment of the time and shows how the rulers catered to the religious sentiments of different religious communities. Besides, the cult icons and wall panels were often used by rulers as political allegories and metaphors to legitimize their claim to kingship. Calukya architecture provides interesting examples of the deployment of such visual metaphors to seek royal legitimation.

Although there are few representations of saptamātṛikās (seven divine mothers) in the Calukya imagery, they figure prominently in the inscriptions of the early Calukyas (Figure 12). The royal inscriptions claim that the early Calukyas ‘were protected by the saptamātṛikās’ (Padigar 2010:lxix). This claim to divine protection is visually portrayed in a unique way in the Rāvaṇa Phadi cave in Aihoḷe. Locally known as Rāvaṇa’s rock (phadi), this cave temple is generally associated with Maṅgaleśa (592‒610 CE). The northern chamber of the cave depicts a ten-armed Naṭarāja flanked by saptamātṛikās along with Pārvati and diminutive Gaṇeśa and Subramanya. The inscription just beneath the sculpted Naṭarāja icon mentions the name Raṇavikrānta, Maṅgaleśa’s second name. The juxtaposed reading of inscriptions and the sculptural panel (Michell 2014:13) suggests that the Naṭarāja icon may have represented the deified form of the king himself, who is shown flanked by saptamātṛikās providing him divine protection.

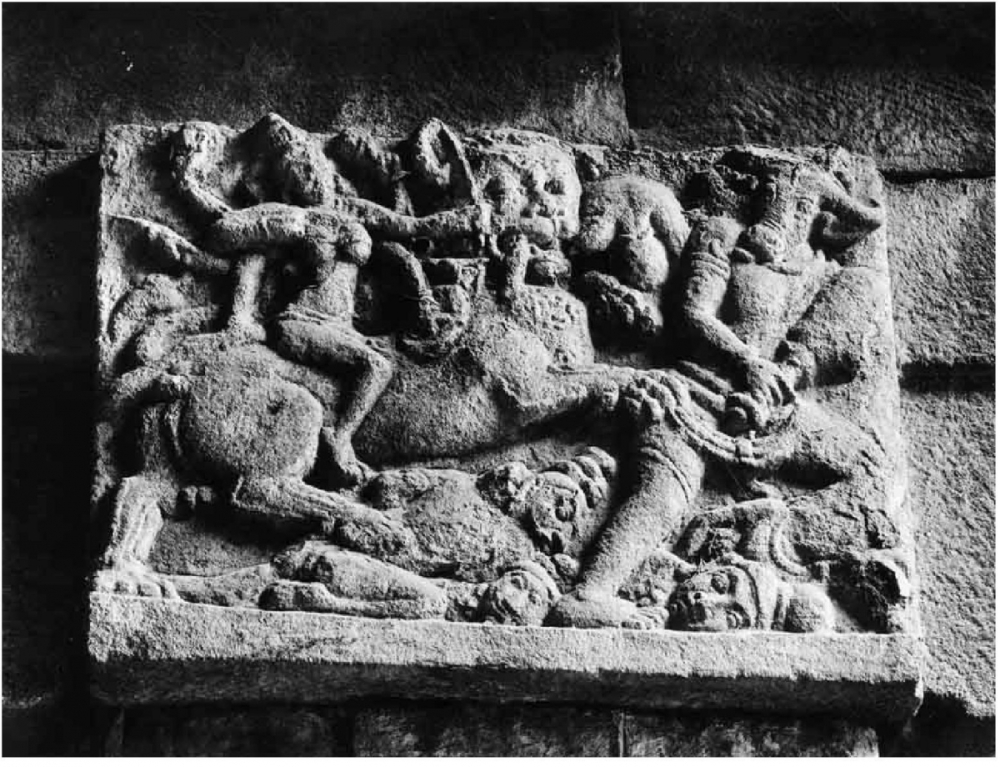

Another sculptural motif that is used for political allegory by the early Calukyas is the Varāha (boar) incarnation of Viṣṇu (Figure 13). Not only is Varāha one of the most commonly depicted icon in Calukya imagery but also their dynastic emblem. As one of the ten major incarnations of Viṣṇu, the boar avatāra is known for rescuing the earth, Bhūdevī (personified as a female goddess). The god’s role as the preserver of the earth was perhaps appropriated as a political allegory for showing Calukyas as rescuing their realm. The use of religious mythology as the political allegory is clearly apparent from the representation of Varāha in Cave 3 at Bādāmi.

While the wall panel portrays Varāha rescuing Bhūdevī and firmly crushing the serpent demon below his feet, the pilaster on his right is engraved with an inscription of Maṅgaleśa, brother of Kīrtivarman, recording the triumphal military campaigns and prowess of the brothers. The location of the inscription next to the Varāha icon is not a coincidence but was perhaps a premeditated act to stress the message of the inscription and draw parallels with the Varāha icon.

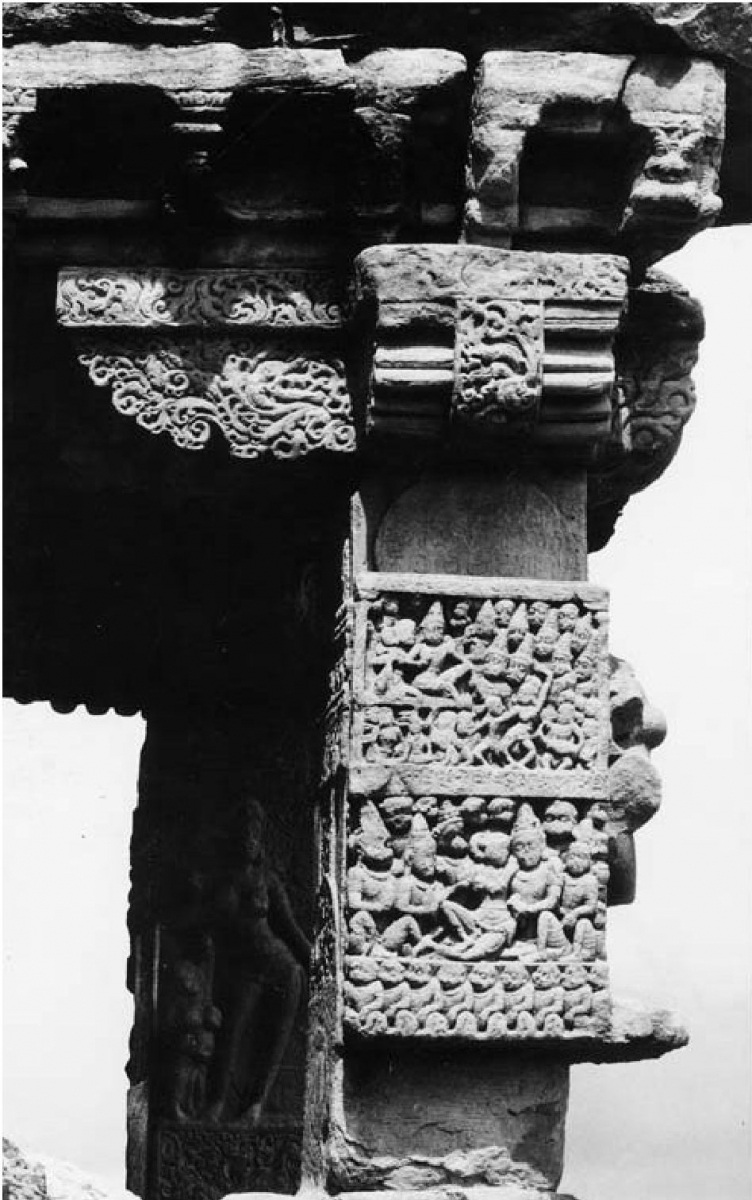

The iconographic programme of the Calukya temples also includes the representations of the glorious scenes from the Ramāyana and Mahābhārata. The episodes from the epics are usually portrayed on the basement friezes or in some isolated niches such as in the Mālegitti Śivālaya and Virūpākṣa temple. But quite distinct from the earlier examples, the Pāpanātha temple at Paṭṭaḍakal has a fully conceived cycle of epic imagery portrayed on the walls of the temple.

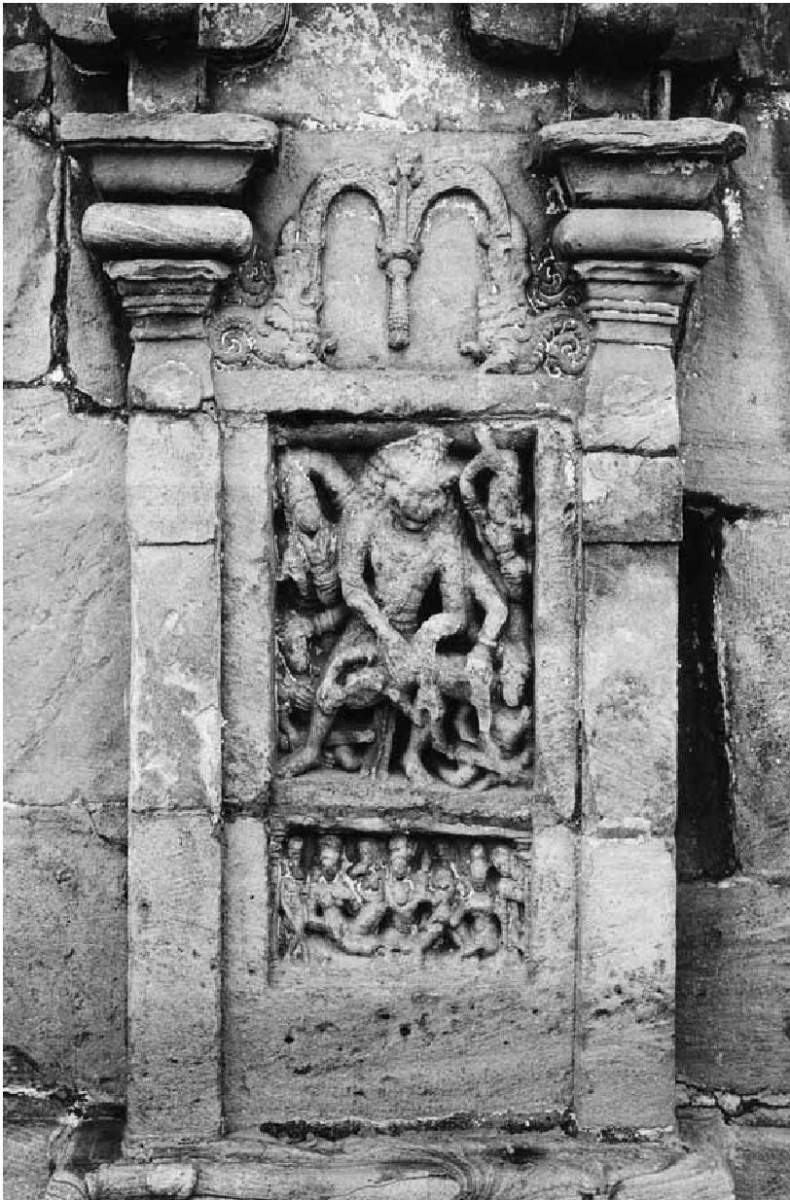

Built towards the end of the rule of the early Calukya dynasty, the Pāpanātha temple (Figure 14) has an unprecedented iconographic programme which makes a bold statement about the actions and character of its patron, Kīrtivarman II. The south walls of the temple present the most extensive depiction of the Ramāyana whereas the events from the Mahābhārata are stretched across the north wall. The Ramāyana sequence begins with king Daśaratha performing the fire sacrifice and ends with the monkeys building the bridge to Laṅkā, and the battle between Rāma and Rāvaṇa. Illustrations from the Mahābhārata are lesser in number but elegantly portray Śiva as a forest hunter, Arjuna’s penance and their fight over a boar. The climactic scenes from both the Ramāyana and Mahābhārata culminate at the front porch pillars. The final scene of the Ramāyana sequence shows the double coronation of king Sugrīva, who sits with his queen and his subjects, and of Rāma, who is shown seated with Sītā, Lakṣmana and Hanumāna in the lower register.

The right-hand column of the front porch depicts the climax of the Mahābhārata, with Arjuna riding a chariot and valiantly fighting the crowd of enemies. The iconographic placement of the climactic scenes right at the entrance of the temples is an intentional device to draw parallel between the patron and the ideal king Rāma, and between the patron’s military prowess and that of Arjuna. Helen J. Wechsler argues that the scenes of coronation (Figure 15) and military victory, the two most important identifying features of kingship, were meant to make direct references to the royal patron, Kīrtivarman II (Wechsler 1994). At the time of political crisis, when the Rāṣṭrakūṭa power was escalating, Kīrtivarman II was in the need for legitimation, and draws parallels with the righteousness of Rāma and prowess of Arjuna cemented his claim to kingship (Wechsler 1994).

Most of the early Calukya monuments resulted from the patronage from the royal family. The nature of patronage qualifies the use of dynastic designation with the architecture of the period as opposed to other examples in ancient India where chronological and regional labels are suitable. The Calukyas had a considerable effect on the art and architecture as their political ideology finds expression in the iconographic programme of the temples. It suffices to say that magnificent temples of Bādāmi, Aihoḷe and Paṭṭaḍakal were not just the result of the piety of Calukyas but were also bold statement of power and devices of legitimation.

References

Bolon, Carol Radcliffe. 1981. ‘Early Chalukya Sculpture'. PhD thesis, University of New York.

Dikshit, D.P. 1980. Political History of the Chālukyas of Bādāmi. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

Fleet, J.F. 1882. The Dynasties of the Kanarese Districts of the Bombay Presidency.Bombay: Government Central Press.

Huntington, Susan L. 1993 [1985]. Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. New York and Tokyo: Weatherhill.

Lippe, Aschwin. 1967. ‘Some Sculptural Motifs on Early Cālukya Temples’, Artibus Asiae 1: 5‒24.

______.1971. ‘Early Chālukya Icons,’ Artibus Asiae 34(4): 273‒330.

Meister, Michael W. and M.A. Dhaky eds. 1986. Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture, South India, Upper Drāviḍadeśa, A.D. 550‒1075. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies.

Michell, George. 2014. Temple Architecture and Art of the Early Chalukyas: Badami, Mahakuta , Aihole, Pattadakal. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

Nagarajaiah, Hampa. 2005. Bahubali and Bādāmi Calukyas. Shravanabelgola: SDJMI Committee.

Padigar, Shrinivas V., ed. 2010. Inscriptions of the Chalukyas of Bādāmi. Bangalore: Indian Council of Historical Research (ICHR).

Tarr, Gary. 1969. ‘The Architecture of the Early Western Chalukyas.’ PhD thesis, University of California.

______. 1980. ‘The Beginning of Dravidian Temple Architecture in Stone.’Artibus Asiae 42(1): 39‒99.

Wechsler, Helen J. 1994. ‘Royal Legitmation: Ramayana Reliefs on the Papanatha Temple at Pattadakal.’ In The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions, edited by Vidya Dehejia. Bombay: Marg Publications.

Acknowledgement

All photographs courtesy of the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS).