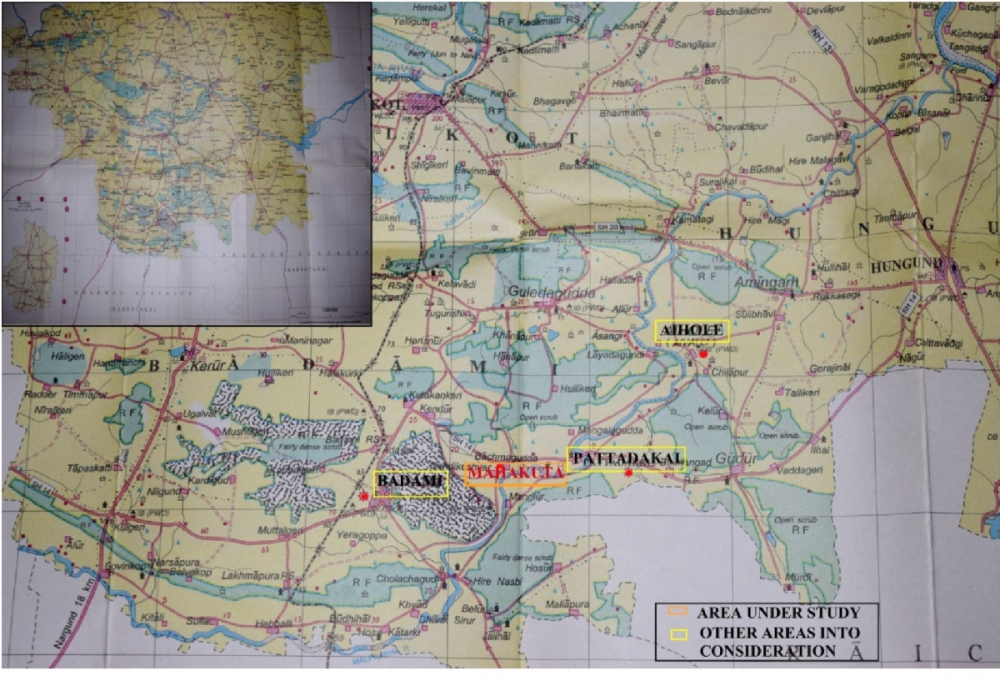

Evolving and thriving at a time when the Deccan was dotted by trivial ‘kingdoms’, the Calukyas of Bādāmi ascended to their powerful position after defeating the Kadambas of Banavāsi or Rāṣṭrakūṭas of Mānapura (Meister and Dhaky 1986:3). This was followed by the fortification of Bādāmi in 544 CE by Pulakēśi I (535/543‒66 CE),[i] after which Bādāmi became the capital of their dynasty, while Aihoḷe sprang near Bādāmi as a temple city. Eventually Mahākūṭa came up as a Śaiva centre and Paṭṭadakal transpired as a royal coronation centre.[ii] Thus, the Malaprabhā basin was occupied by its new overlords, the Calukyas of Bādāmi, who ruled for about two centuries, between the mid-6th century and the mid-8th century CE, until overthrown by the Rāṣṭrakūṭas.

Drawing 1: Map of Bagalkot District, Karnataka.Source: Survey of India. Site Distribution and Photo: Ajeya Vajpayee.

The temples of the Calukyas of Bādāmi may be divided into two distinct yet interrelated architectural phases, namely rock-cut tradition and structural temples (Huntington 1985:282). The structural temples of the Calukyas are unique in their execution—from the temples of Nāgara and Draviḍa idiom. While these temples reveal an assimilation of northern and southern cultural and artistic traditions, they also exhibit a style autochthonous to the region widely recognised as the Karnāṭa-Draviḍa idiom. The temples associated with the Calukyan ruling house saw daylight at Bādāmi, where four cave temples were constructed at the beginning of their rule. Close to their decline, at Paṭṭadakal, nine fully conceived Calukyan temples became representative of the grandeur of Calukyan architecture. In light of the political, religious, and artistic developments that shaped the 6th-century Deccan, this essay aims at a detailed study of the religious structures affiliated to the Calukays of Bādāmi in their core regions of Bādāmi, Aihoḷe, Mahākūṭa and Paṭṭadakal. It intends to trace the development of temple building activity in the region. Further, it strives to understand the architectural and decorative experimentation that characterised the temples of this region and ruling house with the help of specific examples that represent important phases in the evolution of the Calukyan temple architecture.

The Calukyas imbibed the political and social conventions of their precursors (Ramesh 1984:4). Their antecedents, for instance, the Gaṅgas and Kadambas, communicated an evolving culture of religious tolerance, whereby the kings not only patronised their own religious persuasions but also the three major religious systems: Vaiṣṇava, Śaiva, and Jaina. This development was discernible through their art and architectural tradition.[iii] Similarly, the early Calukya kings solicited several religious sects. They patronised the construction of temples dedicated to Viṣṇu, Śiva, Jinēndra, Gaṇeśa, and Sūrya irrespective of their Vaiṣṇava inclination stated in their royal records and validated by their Varāha (boar) emblem. Although it bore the title Parama-Bhāgavata (Padigar 2010:9‒10), Mangalēśa and Pulakēśi II sponsored the construction of the Śaiva Rāvaḷaphaḍi cave and the Jaina Mēguṭi temple, respectively, at Aihoḷe. The later kings were also compassionate to other religious sects. While Vinayāditya observed the installation of the Hindu trinity, Brahmā-Viṣṇu-Maheśa, in the triple-celled Jambuliṅga temple,[iv] Vikramāditya II, perhaps a Śaiva, made a grant to the sun god of Aihoḷe Durga temple.[v]

Bādāmi

Located at the mouth of a gorge between two rocky hills that surround a water reservoir called Agastya Tīrtha from the other three sides, Bādāmi is illustrious in the pages of Indian history as the former metropolis of the most powerful overlords of the Deccan, the Early Western Calukyas of Bādāmi. The site stands out for preserving some of the earliest monuments and inscriptions of the dynasty. While the former reflects on the religious affiliations and architectural developments, the latter provides answers to questions on dating and patronage of these structures. The monuments under study are: Caves I, II, III and IV, Upper Śivālaya, Lower Śivālaya, and Mālegitti Śivālaya.

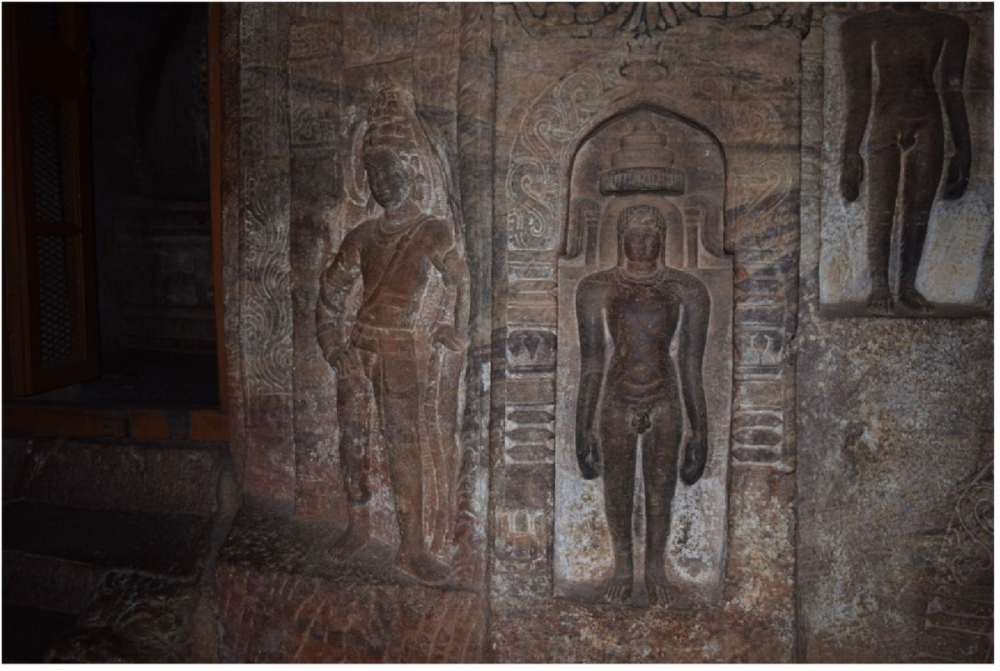

The cave temples at Bādāmi exhibit a simple layout consisting of a pillared veranda followed by a pillared maṇḍapa (hall) and a garbhagṛha (sanctum) at the rear. While Cave I is dedicated to Śiva, Caves II and III are Vaiṣṇava, and Cave IV is Jaina. The larger ornamentation programme of the caves includes colossal panels set into niches. Minor carvings consist of gaṇa (goblin) friezes on the base mouldings of caves I, II and III (Figure 1), detailed carving on the necks of square pillars neatly arranged in the verandas and maṇḍapas, elaborate ceilings, doorways, and the bracket figures placed at the juncture of pillars and ceilings. Cave IV is unique. In its present state this cave is distinguishable from the others by its Jaina persuasion and its distinct carvings of tīrthaṅkars (the omnipresent spiritual teachers of the Jains) on its pillars (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Bādāmi, Cave II, adhiṣṭhāna, gaṇa frieze

Figure 2: Bādāmi, Cave IV, maṇḍapa, tīrthankar on pilaster.

The chief iconography of Cave I includes an eighteen-armed Naṭaraja in a projecting cell to the right end of the facade. Śiva here is accompanied by Nandi (his vāhana or vehicle), Gaṇeśa, and a drummer. The left end of the facade represents a dvārapāla (door-guardian). Above this panel lies a small sculpture of Umā-Maheśa seated on Nandi. The veranda houses the sculpture of Harihara accompanied by consorts and Ardhanārīśvara to the right. Further inside, the main maṇḍapa contains an image of Durgā Mahīśāsuramardinī with Mahīśa in animal form. She is flanked by Gaṇeśa on the right and Kārtikēya on the left. Other meagre carvings include figures of Gajalakṣmī, seated Śiva and Pārvatī, Śeṣaśāyi Viṣṇu, Narasiṁha Viṣṇu, Gaṇeśa, and two devotees worshipping Śivaliṅga, depicted on corbel faces. The garbhagṛha enshrines the Śivaliṅga. This Śaiva shrine is dated to the 6th century CE.

In Cave II, the projecting cell of the facade represents two life-size dvārapālas on each end accompanied by their female partners. The facade to its right accommodates a sculpture of Trivikrama and Varāha Viṣṇu to its left. Other minor sculptures of the cave include Viṣṇu on his vehicle in the central nāsi (gavākṣa, 'caitya-dormer' motif) over the Varāha panel and Naṭaraja over the Trivikrama panel, Kārtikēya in a medallion, Lakulīśa and Pārvatī on the corbel face, and Gaṇeśa, Bhairava and Brahmā on the pillars of the maṇḍapa. Kṛṣṇa narratives are carved on the bays of the maṇḍapa. They depict scenes of Kṛṣṇa being carried to Gokula, stealing butter, Kāliyadamana, etc. These are the earliest known narratives of Calukya art. The garbhagṛha holds the Śivaliṅga. An inscription from the cave, magan Aḍamari, (‘son [named] Aḍamari’) (Meister and Dhaky 1986:4), possibly a cognomen of Pulakēśi II, assigns this cave to his reign.

The chief sculptural programme of Cave III, like Cave II, is Vaiṣṇava. It consists of a number of colossal panels set into niches, depicting various avatāras (forms) of Viṣṇu. The niche jutting out of the veranda accommodates a life-size Trivikrama to its right and an eight-armed Viṣṇu at the obverse end. The veranda towards its left end shelters the most spectacular, gigantic sculpture of Viṣṇu seated on śeṣa (the king of nāgas, upon whom Viṣṇu is often depicted as resting). The adjacent wall represents Viṣṇu in his Varāha avatāra (Figure 3). This niche is important as it records an important dedicatory inscription to its left, on a pilaster:

Maṅgalīśvara created a layana [Cave temple] of god Mahā-Viṣṇu and made a grant of Village Lañjīśvara [Identified with Nandikēśvara near Mahākūṭa] for Nārāyaṇa-bali and for feeding 16 Brāhmaṇas in that temple. It is also states that the merit accruing from this act of piety should go to his brother Kīrtivarma. (Padigar 2010:10‒11)

Figure 3: Bādāmi, Cave III, veranda, Varāha Viṣṇu with Mangalēśa’s inscription

According to Susan Huntington, the placement of the royal inscription next to the Varāha relief was preconceived (Huntington 1985:285). Varāha that occurred on the dynastic banner of the Calukyas symbolised their role as the protector of the earth, while also indicating the kings as virtual incarnations of Viṣṇu. Other cave enhancements include the highly ornate ceiling panel that contains a relief of Garuḍa and Viṣṇu with eight dikpālas (guardians of directions). The garbhagṛha invariably houses Śivaliṅga, which is not its original altar image. The above-discussed inscription dates the cave to 578 CE and attributes it to the rule of Kīrttivarmā I. The grandeur and embellishment of this cave makes it the most impressive among the Bādāmi lot. The main sculptures of Cave IV include Pārśvanātha (23rd tīrthankar) paired with serpent Dharnendra, and Pārśvanātha paired with Bāhubali,[vi] at the two ends of the main maṇḍapa. The ardhamaṇḍapa (half-hall) depicts sculptures of Mahāvīra on both the sides. The garbhagṛha carries an oblong pedestal platform at the rear end and depicts Mahāvīra surrounded by chowri-bearers (fly-whisk bearer).

The three structural temples under consideration: the Upper Śivālaya, Lower Śivālaya and Mālegitti Śivālaya, have homogenous plans, consisting of a mukhacatuṣkī (four-pillared porch), gūḍhamaṇḍapa (closed hall), and a garbhagṛha. However, the Upper Śivālaya has partly lost its mukhacatuṣkī and gūḍhamaṇḍapa. The Lower Śivālaya is comparatively simpler in plan with a maṇḍapa and garbhagṛha. As for the elevation, the Lower Śivālaya and the Mālegitti Śivālaya rise into a two-tiered Draviḍian śikhara (superstructure) with an octagonal cupola (viṣṇucchanda). The Upper Śivālaya rises into a three-tiered Draviḍian śikhara with an oddly fixed square śikhara (brahmacchanda) and a missing finial. All the three shrines face the east. The suffix ‘Śivālaya’ appended to the name of these temples is a misnomer, as will be revealed by their sculptures.

These structural temples retain a number of features from their excavated counterparts. The gaṇa friezes executed on the base mouldings of Caves I, II, and III are continued on the Upper, Lower, and Mālegitti Śivālayas (Figure 4). Indeed, the layout of these temples is no different from the rock-cut caves, the verandas have simply been replaced by mukhacatuṣkīs. There is, however, definitely a departure from the cave architecture in terms of the development of the superstructure over the vimāna (temple), path for circumambulation (sāndhāra prasāda), the execution of latticed windows (jāla-vātāyana), the chief iconography of the temple unfolding on the bhadra (central) niches of the temples, the beginning of narrative panels, and use of miniature shrines to embellish the exterior walls of the temples. This is not to say that the Bādāmi caves and the Bādāmi temples represent linearity in terms of their construction.

Figure 4: Bādāmi, Mālegitti Śivālaya, adhiṣṭhāna, gaṇa frieze

Figure 5: Bādāmi, Lower Śivālaya

The sacred imagery of Upper Śivālaya unfolds on the bhadra (central) niches of the vīmāna (exterior walls of the sanctum). It represents Gōvardhan on the south, Kālīyadamana on the west, and Narasiṁha on the north. The kaṇṭha (neck) moulding of the adhiṣṭhāna (base moulding) exhibits narratives from the Kṛṣṇa myth on the west and Rāma’s legend on the south. Legends of Rāma also appear at the west end of the maṇḍapa. These narrative friezes appear for the first time on the structural temples of the Calukyas. Stylistically, the Upper Śivālaya is dated to the first half of the 7th century CE. The Lower Śivālaya (Figure 5) lacks carving on its bhadra niches and adhiṣṭhāna. It has been suggested that the bhadra niches manifested Śaiva icons now built into a gateway nearby (Meister and Dhaky 1986:28). The garbhagṛha contains an ovular pīṭhikā (pedestal) with no Śivaliṅga. The oval shape of the plinth led Soundararajan to suggest that the temple belonged to Gaṇeśa (Meister and Dhaky 1986:26). The suggestion seems reasonable as the doorway attendants are gaṇas.

In disagreement with Soundararajan, Tartakov contended the temple to be a Vaiṣṇava shrine based on the Kṛṣṇacarita scenes from the Bādāmi museum. He attributed the narratives to the adhiṣṭhāna of this temple (Meister and Dhaky 1986:28). This structure is dated to the first half of the 7th century CE. The still worshipped Mālegitti Śivālaya depicts figures of Viṣṇu (south) and Śiva (north) on the bhadra niches of its maṇḍapa. Representations of Varāha Viṣṇu, Umā-Maheśa, Gaṇeśa, Vaikuṇṭha Viṣṇu, Trivikrama, Narasiṁha, Naṭarāja, Kārtikēya, Durgā, and others appear on the gavākṣa (dormer) motifs, on the eaves of the entablature. The lalāṭabiṁba (lintel) of the doorway to the sanctum houses the sun god Āditya. The garbhagṛha enshrines Śivaliṅga, which is certainly a later replacement. According to eminent art historians, the temple was originally dedicated to Sūryanārāyaṇa and not Śiva, indicated by the image carved on the lintel of the sanctum doorway. The temple is dated to the late 7th century CE in the reign of Vikramāditya I (Meister and Dhaky 1986:41).

Aihoḷe

The picturesque village of Aihoḷe (approximately 25 kilometres away from Bādāmi) is located on the banks of river Malaprabhā. It is historically significant for its prolific temple remains of the Early Western Calukyas. Once the capital of this eminent dynasty, the erstwhile Ahivaḷḷi, Ahivoḷal or Āryapura, now Aihoḷe, is home to some of the finest royal establishments that reveal the architectural development in the region and religious temperament of its sovereigns and other elite patrons. The structures under discussion are the Rāvaḷaphaḍi cave and the Mēguṭi, Durga, and Lāḍ Khān͂ temples.

The Rāvaḷaphaḍi cave exhibits a layout similar to the Bādāmi caves with two subsidiary shrines on the north and south of the pillared maṇḍapa. However, this is not to suggest the latter’s pre-existence. Despite its complex plan and well-decorated interior, this cave is considered the earliest among the cave series at Bādāmi and Aihoḷe. The larger ornamentation programme of the cave is in the form of sculptures manifested on its various parts. The facade on its protruding walls display Śiva as dvārapālas on both sides (they hold triśula or trident which is an attribute of Śiva). The subsidiary shrine on the left side of the maṇḍapa contains a relief of Naṭarāja accompanied by colossal figures of saptamātṛkās (seven divine mothers)[vii], four to his right and three to his left. This shrine on its external wall depicts Śiva as dvārapāla and Ardhanārīśvara. The shrine to the right provides room to the sculptures of Harihara and Gaṅgādhara Śiva on the opposite sides of the extending walls of its facade. Gaṅgādhara Śiva is accompanied by Pārvatī, Bhagīratha, and river goddesses Gaṅgā, Yamunā, and Saraswatī in feminine form touching the crest of Śiva. The antechamber to the main shrine displays Varāha Viṣṇu and Durgā Mahīṣāsuramardinī to the north and south, respectively. The ceiling of the antechamber depicts Viṣṇu with his vāhana and two attendants. Inside the garbhagṛha, on its pīṭha, is a Śivaliṅga. On the basis of an inscription found on the adhiṣṭhāna in the maṇḍapa of this cave, ‘Śrī-Raṇavi[krāntan]’[viii] (Padigar 2010:260), art historians are led to attribute this structure to the reign of Mangalēśa between the 6th and 7th centuries CE.

The three structural temples under consideration, the Lāḍ Khān͂, Mēguṭi, and Durga temples, show development in architectural layout, from simple to elaborate. However, it is not a signifier of their chronological sequence. Lāḍ Khān͂ reveals a simple plan—similar to the cave temples—consisting of a mukhamaṇḍapa (entry-hall), pillared maṇḍapa, a small shrine at the rear end, and a gṛhapiṇḍī (wall-cube of the upper storey), which is perhaps an interpolation. The Mēguṭi temple displays an elaborate plan, in that it comprises a mukhamaṇḍapa, ardhamaṇḍapa, square sāndhāra vīmāna and a gṛhapiṇḍī. Authorities deem the mukhamaṇḍapa and gṛhapiṇḍī as later additions. The Durga temple exhibits an impressive and unique plan. It consists of a mukhacatuṣkī, maṇḍapa and an apsidal garbhagṛha rising to a misfit Nāgara śikhara (Latina type). It also has an additional peristyle with a circumambulatory passage surrounding the entire temple.

Thus, at Aihoḷe the uniqueness of Calukyan architecture begins to show. With Lāḍ Khān͂, the maṇḍapa style of temple becomes a part of the religious landscape of the Calukyas. The Mēguṭi boasts great length, which later became one of the distinctive features of Calukyan temples. Finally, the Durga temple is unmatched with its apsidal plan, two circumambulatory paths, its admixture of northern and southern architectural tradition, with its Draviḍian vimāna and Nāgara śikhara, and elaborate interior carvings in forms of pillars, ceilings, doorways, adhiṣṭhāna (Figure 6), and brackets (Figure 7). Furthermore, the religious dedications of these temples are different from one another. While the Mēguṭi temple is a Jaina shrine, the other two shrines are dedicated to Sūrya.

Figure 6: Aihoḷe, Durga temple, adhiṣṭhāna

Figure 7: Aihoḷe. Durga temple, mukhamaṇḍapa, female bracket figure

The Mēguṭi temple in Aihoḷe is devoid of any external ornamentation. The altar image is damaged too. Although, artistically the temple does not yield anything different from its precursors, it is historically significant because of an engraving on its eastern wall. The foundational epigraph discloses a generous amount of information about the temple’s religious affiliation and its patron. It opens with the praise of holy Jinēndra, followed by a praśasti (eulogy) in praise of its patron, Pulakēśi II. It dates the temple to 634‒35 CE (Padigar 2010:37‒40). The chief iconographic programme of the Durga temple unfolds in the niches in the solid wall of the ambulatory path. The depictions include Durgā Mahīṣāsuramardinī and Viṣṇu towards the north, Nandi and Narasiṁha towards the south, and Viṣṇu with Garuḍa and a female attendant, and Varāha Viṣṇu in the apse. The lintel of the gūḍhamaṇḍapa represents Garuḍa holding nāga-tails. The garbhagṛha is empty. It is difficult to comment on the religious dedication of this temple as it adorns both Śaiva and Vaiṣnava icons. Also, the temple must not be mistaken for a shrine to Durgā, suggested by the name it carries, as the temple was named after a nearby fort (durga) (Huntington 1985:332). A donative inscription on the north wall of its pratōli (entrance gateway) signifies the temple’s dedication to the sun god.[ix] On the basis of the character of this inscription, K.V. Ramesh dated the temple not later than the 8th century CE (Padigar 2010:218‒19).

The chief ornamentation scheme of the Lāḍ Khān͂ temple consists of its sculptures portrayed on the central niches of its gṛhapiṇḍī. The north wall is executed with a sculpture of Ardhanārīśvara, the west wall with Sūrya, and the east wall with Viṣṇu. Other carvings include a depiction of Garuḍa holding nāga-tails on the lintel of the main maṇḍapa, and Varāha, śaṅkha (conch), cakra (wheel), darpaṇa (mirror), catra (umbrella) and cāmara (fly-whisk) in the mukhamaṇḍapa. The carvings in the mukhamaṇḍapa suggest the royalty of the temple. The centre of the main maṇḍapa is occupied by a huge Nandi. The religious dedication and time period of this temple are deeply contested.[x] However, on stylistic grounds it is dated to the end of 7th century CE (Meister and Dhaky 1986:44‒45).

Mahākūṭa

Not very far from Bādāmi, Mahākūṭa is a unique conglomerate of twenty-seven old and new stone temples that stand around a masonry tank famously known as Viṣṇu-Puṣkariṇī. A generous number of temples in the complex belong to the time period of the Calukyas of Bādāmi and were in fact commissioned by royalty. The involvement of Calukyan royalty at Mahākūṭa can be ascertained from the Mahākūṭa pillar inscription, better known as Mangalēśa’s dharma-jaya stambha, which once stood inside this complex. The seventeen-line inscription on the pillar recorded a land grant to the dēvadrōṇi (idol procession) of the Mahākūṭēśvara temple by Mangalēśa in continuation of the grants made by his father and brother Pulakēśi I and Kīrttivarmā I, respectively (Padigar 2010:12‒15). Since then scholars have tried to examine the relationship between Mangalēśa’s pillar and the present Mahākuṭēśvara temple. However, no firm conclusion has been drawn and the debate on its date, location, and dedication still continues.

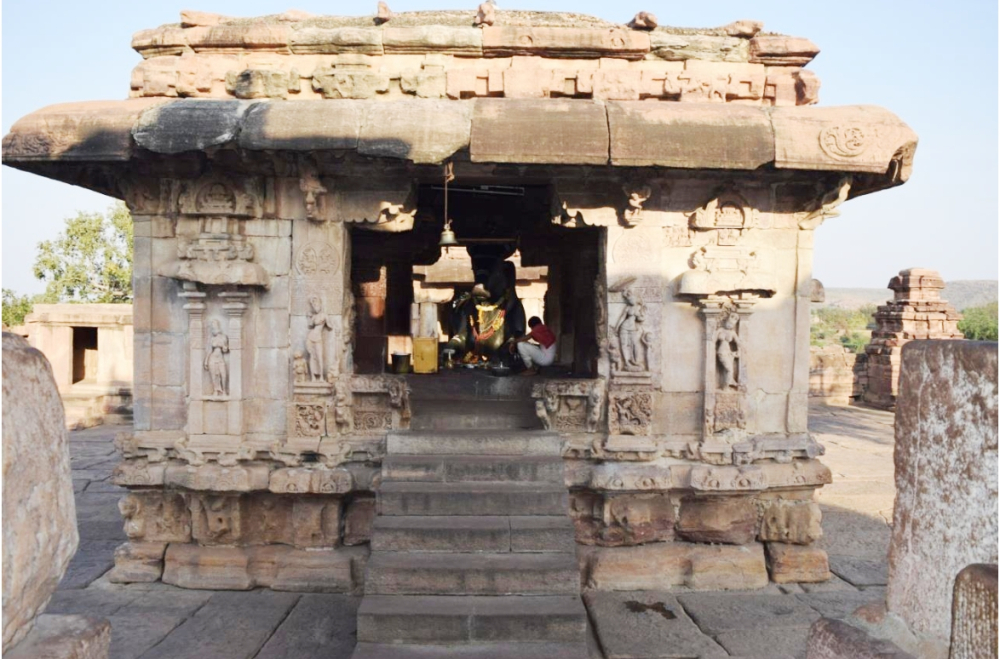

The temples of the Mahākūṭa enclosure are in northern and southern styles. They exhibit a simple plan, with most of the temples comprising a mukhacatuṣkī and garbhagṛha. The ornamentation is dismal. The temples at Mahākūṭa can be classified into four types on the basis of their architecture, namely, flat-roofed (Figure 8), northern style (Figure 9), pyramidal style (Figure 10), and Draviḍian style (Figure 11). Most of the temples from the complex are built in pyramidal style. The two most consequential temples of the enclosure follow the Draviḍian idiom. It can be said with some certainty that Mahākūṭa represents an experimental phase in Calukyan architecture, whereby a number of architectural styles converge until the fully developed Calukyan masterpieces are conceived at Paṭṭadakal. The temples under consideration are the Caturamukhaliṅga Maṇḍapa, Vīrūpākṣēśvara, Pinākapāṇi, and Mallikārjuna temples. Each of these shrines represents the four architectural styles witnessed at Mahākūṭa.

Figure 8: Mahākūṭa, Caturamukhaliṅga pavilion

Figure 9: Mahākūṭa, Vīrūpākṣēśvara temple

Figure 10: Mahākūṭa, Pinākapāṇi temple

Figure 11: Mahākūṭa, Mallikārjuna temple

The Caturamukhaliṅga maṇḍapa is an open pavilion in the Viṣṇu-Puṣkariṇī (Figure 8). It is devoid of any external ornamentation. However, its pillars are heavily carved and resemble the nearby Sangamēśvara temple. The short square pillars with hexagonal necks are carved with lotus medallions, leaf vine band, and pearl-festoon band. The pillars culminate into wave-like brackets that support a curbed entablature. The mukhaliṅga in the centre sits on a square base and represents four or five different aspects of Śiva.[xi] The flat roof of the pavilion is capped by a ribbed āmalaka (crowning ribbed member of Latina-Nāgara temples). Although, the mukhaliṅga is often ascribed to the post-Calukyan period on the basis of its stone colour (Radcliffe 1981:180; Tarr 1969:237), the position of the pavilion viz-a-viz the other shrines indicate a date in the first half of the 7th century CE.

The Vīrūpākṣēśvara temple is the most ornate and aesthetically pleasing shrine of Mahākūṭa (Figure 9). It is the only temple inside the enclosure that is dedicated to Viṣṇu. It is constructed in Nāgara style, with each storey rendered into bhūmī-āmalaka-bhūmī (storey of the temple consisting of a ribbed crowning member or āmalaka sandwiched between two rectangular slabs or bhūmīs). It has a ‘misfit’ śukanāsa (antefix on the superstructure),[xii] bearing a Naṭarāja in its cavity. The temple also incorporates kakṣāsana (seatback) on its entry-porch (Figure 12), an architectural element also met at the Lāḍ Khān͂ temple. The kakṣāsana has detailed carvings of lotus band, diamond band, mithunas (amorous couples) and pūrṇa kumbha (vase of plenty) motifs on the outside. The carved doorway of the sanctum bears a Draviḍian entablature, which becomes a common practice hereafter (Figure 13). The exterior walls of the temple are met with sculptures on their bhadra niches. They represent Varāha Viṣṇu on the south, four-armed Viṣṇu on the west, and Narasiṁha Viṣṇu on the north. Due to its artistic similarity with the nearby Sangamēśvara temple, it is apt to date this shrine to the second half of the 7th century CE.

The Pinākapāṇi temple is a five-storeyed pyramidal shrine with a mukhacatuṣkī and garbhagṛha (Figure 10). The striking features of this temple are its kakṣāsana and sanctum doorway. The former possesses carvings on the outside depicting mithunas, foliage bands, vyālas (composite animals), and diminutive pilaster motifs. The doorway of this temple is recessed into four jambs (Figure 14). The innermost jamb has nāgaśākhā (band with snake), followed by a patraśākhā (leaf band), plain jamb, and latā-patraśākhā (vine-leaf band). The basement panels on both sides are carved with a male, a dwarf, and a female. The ornamentation on the exterior walls of this temple is no different from the other smaller temples in the complex. The central iconographic programme of this temple is delineated on the bhadra niches. They depict a two-armed Lakulīśa on the south and Śiva with Nandi [?] on the north. The depiction of river goddesses [?] in the basement panels of this temple, which was incorporated in Calukya art from the reign of Vinayāditya onwards (681‒96 CE), lends a date towards the end of 7th century CE to the temple.[xiii]

Figure 12: Mahākūṭa, Vīrūpākṣēśvara temple, kakṣāsana

Figure 13: Mahākūṭa, Vīrūpākṣēśvara temple, doorway to the sanctum

Figure 14: Mahākūṭa, Pinākapāṇi temple, doorway to the sanctum

Figure 15: Mahākūṭa, Mallikārjuna, gūḍhamaṇḍapa, checker-board latticed window

Figure 16: Mahākūṭa, Mallikārjuna, gūḍhamaṇḍapa, Uma-Maheśa ceiling panel

The Mallikārjuna temple, like the Mahākūṭēśvara temple, is the biggest and the most elaborate temple of the complex (Figure 11). On plan it consists of a mukhacatuṣkī, gūḍhamaṇḍapa and a garbhagṛha with pradakṣiṇāpatha. It rises in a two-storeyed octagonal śikhara. It also has a detached Nandi maṇḍapa. The temple is variously embellished with sculptures, latticed windows, narratives, ceiling panels and carvings on the pillars and doorways. The sculptures of the temple are placed on the subhadra (central offset of bhadra) niches. It houses a four-armed Viṣṇu (south), four-armed Śiva (west) and Ardhanārīśvara (north) on the outer wall of the garbhagṛha and four-armed Viṣṇu (north) and four-armed Śiva (south) on the exterior walls of the gūḍhamaṇḍapa. The latticed windows of the temple boast checker-board (Figure 15), matsya-cakra (fish wheel), and cross bar patterns with north and south Indian pediment. Although insignificant in terms of subject, the narratives are portrayed on the neck moulding of the six-course adhiṣṭhana. The interiors of all the Mahākūṭa temples lack carving but this temple has three ceiling panels in the gūḍhamaṇḍapa, of which the panel depicting Umā-Maheśa on a sinuous Nandi is the best (Figure 16). The Nandi maṇḍapa in front of the temple is an open four-pillared pavilion with modest carving. Given the overwhelming similarities between the Mahākūṭēśvara and Mallikārjuna temples, it wouldn’t be incorrect to suggest that the two were constructed in the same time period, that is, at the end of 7th century CE.

Paṭṭadakal

Situated on the left bank of the river Malaprabhā, Paṭṭadakal is acclaimed as a royal coronation centre. Its royalty is amply suggested by the royal temples and inscriptions found from the site.[xiv] It is believed that this site developed after Bādāmi, Aihoḷe and Mahākūṭa. The site exhibits nine fully conceived temple forms of both northern and southern Indian origin, enclosed within a complex. The large variety of architectural forms, embellishments, amalgamation of styles and motifs witnessed at this site renders it different from the earlier sites of Bādāmi, Aihoḷe and Mahākūṭa. Today, Paṭṭadakal is recognised as a world heritage site. The temples under consideration are the Vīrūpākṣa and Pāpanātha (200 meters away from the main complex).

The temples in discussion exhibit complex plans. The Vīrūpākṣa temple, originally known as Lōkēśvara, on plan is a four-storeyed sāndhāra vīmāna consisting of a mukhacatuṣkī, gūḍhamaṇḍapa, two subsidiary shrines in the antarāla (antechamber) and a garbhagṛha that blooms into a Draviḍian śikhara. It also has an ornate Nandi maṇḍapa (Figure 17). It was once surrounded by an enclosure wall with niches and gopurams of which nothing remains. The Pāpanātha temple is built in northern style (Figure 18). On plan, it consists of a mukhacatuṣkī, two subsequent maṇḍapas, sabhāmaṇḍapa (meeting hall) and ardhamaṇḍapa and a garbhagṛha with circumambulatory passage.

The Vīrūpākṣa temple is heavily embellished both on the inside and outside. Various forms of Śiva, Viṣṇu, scenes from legends such as Jatāyuvadha and Ravaṅanugrhamūrtī are met on the recessed walls of the temple. Carvings are also seen on the pillars and ceilings of the temple. They exhibit both divine and non-divine themes such as samudramanthana (churning of the ocean), Śeṣaśayi-Viṣṇu, Sūrya on his vehicle (Figure 19), mithunas, garland-bearers (Figure 20), and surasundarīs (auspicious female motif). The small shrines in the antechamber show sculptures of Gaṇeśa on the left side and Durgā Mahīṣāsuramardinī on the right. The garbhagṛha holds a Śivaliṅga, which is still worshipped. The śukanāsa on the fourth storey represents a Naṭarāja in its cavity. Vikramāditya II’s victory pillar stationed in front of the Mallikārjuna temple dates this temple between 733 and 745 CE (Padigar 2010:236).

Figure 17: Paṭṭadakal, Vīrūpākṣa temple, Nandi maṇḍapa

Figure 18: Paṭṭadakal, Pāpanātha temple

Figure 19: Paṭṭadakal, Vīrūpākṣa temple, gūḍhamaṇḍapa, Sūrya ceiling panel

Figure 20: Paṭṭadakal, Vīrūpākṣa temple, gūḍhamaṇḍapa, pillar carving, garland bearer

The Pāpanātha temple (Figure 18) stands out from all the other Early Western Calukya temples of the time, manifesting scenes of the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata or Kirātarjuniyam on its exterior walls. Possibly the double maṇḍapa of the temple was an intentional effort at the hands of the architect to conceive the two epics on the south and north walls respectively. Labels flanking these chiselled panels were probably added to aid the correct reading of the various scenes from the epics.[xv] While the narratives begin to unfold on the length of the two maṇḍapas, the porch of the temple depicts the climax of the two narratives. The sanctum holds Śivaliṅga. The temple is ascribed to the reign of Kīrttivarmā II (745‒57 CE), built during the low point of the Calukya dynasty.

Thus, the early Calukyan temples generally comprise square sanctuaries with passageways, maṇḍapas and an entrance hall aligned in a single axis, usually running west to east (Michell 2014:18). Some temples are open columnar structures, while others have closed pillared halls divided into aisles from the entrance to the sanctum with frontal and side porches, latter usually seen in later temples. Pillars are usually monolithic with carvings on the neck. They culminate in brackets that serve as meeting point between the pillars and roof. The brackets are often rendered with sculptures, which became a distinct feature of Calukyan temples. The external walls of the temple are raised on a plinth that is moulded in three, four or six courses depending on the time period and complexity of the structures. The early temples usually consist of three to four mouldings while the later ones display six-course mouldings. These mouldings come with lotus bands, diamond bands, leaf bands, flower bands and dormer motifs. The few early and later ones also incorporate narratives in their neck mouldings. The treatment of the wall depends on the style of the temple—Nāgara or Draviḍian. The walls are mostly recessed, the central recess being used for sculptures flanked by pilasters and topped by north or south Indian pediments. The exterior walls of the temple rise into hollow towers topped with pot-like or lotus finials. The various storeys of the towers are met with miniature shrine motifs or bhumi-āmalaka in case of south and north Indian temples respectively.

Conclusion

The Calukyan temple architecture between the mid- 6th and mid-8th century CE comprises a vast corpus of temple remains significant in South Asian art and building tradition. Over one hundred structural temples associated with this dynasty are some of the earliest extant examples of temple building activity in the country, influence of which is witnessed throughout the Deccan. Unfortunately our knowledge about their precursors is dismal, making it difficult to understand their origin or innovations. Despite the difficulties, Calukyan art has received a generous amount of academic attention and this it owes to its notable structures—with various forms, abundant art and sculptural remains, and epigraphic material. T

he prolific building activity under the Calukyas developed over a period of two hundred years. It began with simple rock-cut shrines and ended with complex structural temples. The temples were simple in terms of plan and ornamentation in the beginning, as seen on most of the temples at Bādāmi, Aihoḷe and Mahākūṭa. While Bādāmi and Aihoḷe were scattered on a vast landscape holding temples dedicated to various gods such as Śiva, Viṣṇu, Gaṅeśa, Sūrya, Mahākūṭa emerged as an enclosed temple space holding temples invariably dedicated to Śiva. The latter site, Paṭṭadakal, also evolved as a temple conglomerate with complex temples that represented the zenith of Calukyan architecture.

Although temples from these sites represent various phases in Calukyan architecture—early, experimentation and mature—they exhibit certain characteristics that became idiosyncratic to the Calukyan architecture, such as the ceiling panels, the bracket figures, the great length of their structures and most of all the admixture of northern and southern elements in their temples. These features had a lasting impact on the Deccan art for centuries.

Notes

[i]Tr.,‘He (Pulakēśi I) is stated to have made the hill at Vātāpi a fort invincible from below as well as above.’ See Padigar (2010:1).

[ii]The elaborate Śiva temples of Vikramāditya II’s queens, Lōka-Mahādēvī (the Vīrūpākṣa temple) and Trailōkya-Mahādēvī (the Mallikārjuna temple), reveal Paṭṭadakal’s royal existence.

[iii]Idea borrowed from Hans Bakker’s work ‘Royal Patronage and Religious Tolerance: The Formative Period of Gupta-Vākāṭaka Culture’, an article in which he focuses on four archaeological sites of Udayagiri, Mandhal, Rāmagiri and Mansar to elucidate his hypothesis of emerging religious tolerance in the reign of the Gupta and Vākāṭaka kings. For detailed reference, see Bakker (2010:461‒75).

[iv]The record states: Tr., ‘King’s mother Vinayavatī installed the gods Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Maheśvara at the capital of Vātāpyadhiṣṭhāna....' This inscription is engraved on a pillar in the mukhamaṇḍapa of the Jambuliṅga temple. For detailed reference, see Padiagar (2010:155‒56, inscription 91).

[v]This inscription is engraved on the northern wall of the gateway to the Durga temple. It states: Tr., ‘When Vikramāditya II was ruling over the earth and Rēvaḍi..., this grant was given to the god Āditya of the temple of Komarasiṃga....' For detailed reference, see Padigar (2010:218‒19, inscription 126).

[vi]Soundararajan identifies this sculpture with Gommaṭa. See Soundararajan (1981:79)

[vii]According to a legend these seven mothers were created to aid Śiva in his fight against the demon Andhakāsura.

[viii] It was possibly an epithet of Mangalēśa, also identified in other Calukyan epigraphs. See Padigar (2010:14).

[ix]‘When Vikramāditya II was ruling the earth..., this grant was given to the god Āditya of the temple of Komarasiṃga....’ (Padigar 2010:218‒19).

[x]Earlier art historians have dated this temple to the 5th century CE. However, Tartakov and Bolon provided a later date to the temple because of the presence of Gaṅgā‒Yamunā images on it that were won by Vijayāditya when he was a crown prince. See Jamalagam grant.

[xi]The mukhaliṅga represents: Sadjyota (east), Tatpūrūṣa (west), Vāmadeva (north), Aghora (South) and Ishana (top).

[xii]The antefix seems like a misfit because there is no antechamber in the temple to which the architectural element conventionally serves as a roof.

[xiii]It was Vinayāditya’s son Vijayāditya who as a crown prince fought against the northern kings and won the river goddesses pāli-dhvaja, paḍha and ḍhakkā. For details, see Padigar (2010:150‒53).

[xiv] For a list of inscriptions at Paṭṭadakal, see Padigar (2010:67‒70 and 150‒53).

[xv] See Padigar (2010: 277, 279, 281 and 283).

References

Annigeri, A.M. 1978. 'Religion Under the Chalukyas of Badāmi.' In The Chalukyas of Badami (Seminar Papers), edited by M.S. Nagaraja Rao, 232‒239. Bangalore: The Mythic Society.

Bolon, Carol R. 1981. 'Early Chalukya Sculpture.' PhD thesis, Department of fine Arts, University of New York.

Cousens, H. 1996 [1916]. The Chālukyan Architecture of the Kanarese Districts. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Dikshit, D.P. 1980. Political History of the Chālukyas of Badami. New Delhi: Abhinav Publication.

Huntington, Susan. 1985. 'Hindu Rock-Cut Architecture of the Deccan (Kalacuri and Early Western Calukya Phases).' In The Art of Ancient India, 275‒299. New York: Weather Hill.

Kadambi, Hemanth. 2011. 'Sacred Landscapes in Early Medieval South India: The Chalukya State and Society (ca AD 550-750).' Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Michigan.

Meister, M., and M.A. Dhaky, eds. 1986. Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: South India Upper Drāvidadēśa, Vol. 1, part 2. Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS) and OUP.

Michell, George. 1979. 'Temples of Early Chalukyas: Aihole, Badami, Mahakuta and Pattadakal', Mārg 32 (1): 67‒76.

———. 2014. Temple Architecture and Art of the Early Chalukyas: Badami, Mahakuta, Aihole, Pattadakal. New Delhi: Niyogi Books.

Mohite, Meena M. 2012. Early Chalukya Art at Mahakuta. Delhi: B.R. Publishing House.

Padigar, Shrinivas V., ed. 2010. Inscriptions of the Calukyas of Bādāmi. Bangalore: Indian council of Historical Research (ICHR).

Ramesh, K.V. 1984. Chalukyas of Vātāpi. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan.

Rao, S.R. 1972. 'A note on the Chronology of Early Chālukyan Temples', Lalit Kalā 15: 9‒18.

Soundararajan, K.V. 1981. Cave Temples of the Deccan. New Delhi: ASI.

Tarr, Gary. 1969. 'The Architecture of the Early Western Chalukyas.' PhD thesis, University of California.

———. 1980. 'The Beginning of Dravidian Temple Architecture in Stone', Artibus Asiae 42 (1): 39‒99.