Bengali cookbooks presented a strong case for necessitating the maintenance of a clean, properly arranged and well-ventilated kitchen space. The introduction of germ theory in the nineteenth century made notions of hygiene, pollution, dirt and disease matters of immediate concern. Its influence trickled down to all spheres of social life and the Bengali middle class was no exception. Issues of caste became conflated with apprehensions regarding hygiene, albeit couched in a language of science. The kitchen was identified with domestic purity and governing it with these new dictates also signified the preservation of the class body.

Writer and educationist Dinesh Chandra Sen emphatically stated in Grihasree (1915) that a clean kitchen was essential for cooking. He reprimanded women who wiped their hands on their clothes while performing household chores. He instructed women to use spoons and ladles to serve food.[1] Thus, making a healthy meal for the family meant strict observation of the processes through which the meal was prepared and served. Education was given a cultural definition in the context of culinary skills. Women gaining proficiency in the practice of culinary arts became imperative to the formation of a Bengali social class based on taste. The ideal kitchen setup consisted of a clean cooking space, a well-organised and hygienic storeroom, appropriate utensils and appliances, and the correct arrangement of kitchen and dining-room furniture.[2] This was evident from the structuring of cookbooks, which often provided elaborate guidelines for maintaining the kitchen and its associative paraphernalia.

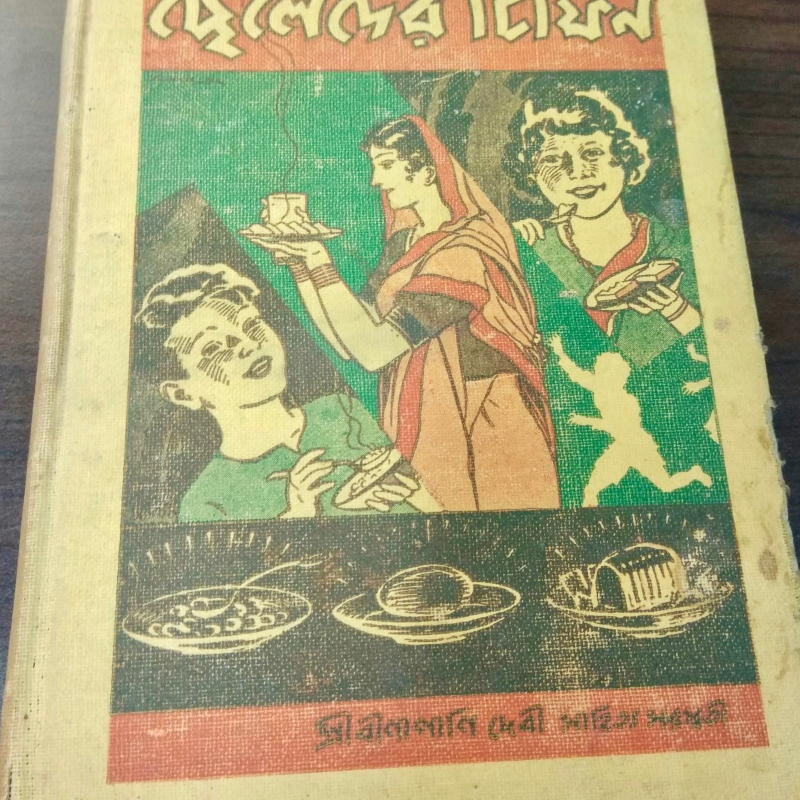

The late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries were a period rife with discussions on hybridity in food practices and the formation of a so-called authentic Bengali cuisine. On one hand, cookbooks freely indulged in incorporating recipes for jam, pies, cutlets and stews and, on the other, there was an endeavour to localise the hybrid. Pragyasundari Debi’s classic work on Bengali food, Amish o Niramish Ahar [Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Food] (1902) attempted this by amalgamating the ‘foreign’ and the ‘indigenous’ by contending that many European food products derived its name from Sanskrit words. Rwitendranath Tagore made similar observations in his work Mudir Dokan [Grocery Shop] (1919) but preferred the terms ‘social interaction’ instead of hybrid.[3] Bipradas Mukhopadhyay preceded his recipes in the first volume of Pak Pranali [Methods of Cooking] (1883) by introducing cabbage and cauliflower since they were new vegetables. He gave instructions on how to choose and clean them.[4]

The mention of garlic and onion were almost absent in the early cookbooks such as Pakrajeswar and Byanjan-Ratnakar. These books claimed to supply recipes of Mughlai cuisine but the conspicuous absence of the two essential ingredients indicated that the Bengali-Hindu readers of the books, distributed in Burdwan, were not yet accustomed to using them in their dishes. However, the anonymously written Pakprabandha (1897), unlike the two previous cookbooks, frequently incorporated use of the two vegetables. This increase in the use of onion and garlic in recipes, supposedly written for the Bengali middle-class Hindus, begins to reflect in changes in diet patterns.

The period also saw the easy availability of foreign food items and new kitchen appliances in the market, including essences for baking, cake and pie moulds, gelatine, and various kinds of bread, health drinks, kerosene stoves and steam cookers. Cookbooks introduced the Bengali-Hindu middle-class to the novelty and pleasure of this aspect of colonial modernity.

The traditional Bengali kitchen witnessed a transition due to the influx of new ideas of cleanliness and hybridity. Utensils made of metals were gradually replacing clay wares, earthen stoves made with a mixture of mud and sand gave way to automated ones, and hospitality rituals were changing with changes in food preparation techniques. Previously, a regular middle-class kitchen would have hari (urn-shaped pot), dekchi (flat-bottomed pot), kadhai (tumbler-like cooking pot), hata (ladle), khunti (spatula), chimte (tong), kolsi (pitcher), haman-dista (mortar and pestle), belna (rolling pins), chaluni (sieves), thala (plate), bnati (bowls), shil-nora (grinding stone with a pestle) and the dexterously used bonti (cleaver-like blade with a wooden base). The practice of keeping two separate bontis for chopping vegetables and for portioning fish or meat is common even today in both urban and rural Bengali homes. The one used for cutting fish or meat is called ansh-bonti (‘ansh’ meaning fish scales). Another interesting variant of the bonti used commonly in the Bengali kitchen for grating coconut was the kuruni. The blade consists of a round serrated piece of metal. In ‘floor-oriented’ cultures, such as Japan and India, especially Bengal, people were accustomed to squatting or sitting on the floor for indefinite periods of time.[5] Thus, women were used to sitting in front of an unan (low earthen stove) or using small stools placed on a slightly raised platform, to chop, slice or cook vegetables, fish and meat in the kitchen. One had to either squat on the haunches or sit on the floor with one knee raised to manoeuvre the bonti or unan. The introduction of Western ovens or even the use of knives required tables and countertops, which required one to stand for functional ease. Writer Chitrita Banerjee says:

How big is the difference between sitting and standing? A cultural universe, when you examine posture in the context of food preparation. In the kitchens of the West, the cook stands at a table or counter and uses a knife. But mention a kitchen to a Bengali, or evoke a favourite dish, and more often than not an image will surface of a woman seated on the floor, cutting, chopping, or cooking. In the Indian subcontinent, especially in its eastern region of Bengal, this is the typical posture.[6]

Women negotiating with these versatile blades formed an important part of Bengali iconography suggesting feminine abilities. In the southern district of Barisal in Bangladesh, prospective brides were asked by their future in-laws to sit at the bonti and finely chop a resistant bunch of kalaishak (grass pea shoots) to be stir-fried for demonstrating their domestic skills.[7] In the kitchen, women often sat on square rectangular platforms made of wood called piri or jolchouki which raised them an inch or two above the floor. The daily ritual of kutno kota (chopping vegetables) was performed sitting on these low stools. Chitrita Banerji notes that this tradition arrived out of paucity of furniture in Bengali homes. It was only after European presence was well established later in the nineteenth century that living or dining rooms became acquainted with furniture such as couches, chairs and tables in Bengal.[8]

Utensils for cooking, storing and serving food were generally made of clay, stone, kansa (bell metal), pital (brass), tamba (copper) and iron. Banana leaves were also widely used to plate food. These were replaced by utensils made of steel and aluminium due to their durability and easy maintenance. But their use was also met with considerable opposition. Pragyasundari Devi objected to the use of aluminium. Bipradas Mukhopadhyay cautioned his readers against the use of metal utensils for cooking. Earthenware was considered the safest and tin coating was highly recommended while using copper utensils. It was feared that these new metals could spread diseases or react with cooked food and render them poisonous. Even greater attention was paid to storing chutneys and pickles. A festive issue of the Ananda Bazar Patrika in 1944 carried an advertisement for Jibanlal Aluminium utensils which claimed that cooking with its vessels helped retain vitamins within food. It was representative of the new dietary science which was making its way. The advertisement further warned buyers against cheaper aluminium utensils made by rival companies which could indeed be harmful for cooking.[9]

A meat safe, a ventilated storage unit designed like a small wooden cupboard covered in wire mesh, was popularised for keeping cooked food. Its four legs would usually rest on four small bowls filled with water to prevent insects from climbing in and contaminating the food. Because of concerns over cleanliness and diseases, meat safes were well adapted into Bengali households by the turn of the twentieth century. Sakuntala Bhattacharya in Adhunik Rannar Boi [New Book of Cookery] (1976) advocated its use in every Bengali kitchen.[10]

Such inventions were precipitated by growing anxiety over hygiene and organisation influenced by Victorian ideas of domesticity. The Icmic cooker, patented by Indumadhab Mallick, was one of the appliances introduced in the market during the early twentieth century. A cylindrical metal steamer, with separate compartments for cooking rice, lentils and vegetables or meat together, the cooker became very popular with the literate population who moved to Calcutta for jobs and bachelors who lived in hostels. It found little mention in cookbooks as women were considered natural cooks who could function without time-saving inventions. Pragyasundari Devi, however, did mention the use of the Icmic cooker along with providing recipes to aid her readers.[11] She also wrote about the importance of cutlery while feasting on various kinds of meats and imported kerosene stoves which eased the process of cooking. These stoves entailed the use of new utensils. Saucepans, also known as bilati hnari, cream separators for boiling large amounts of milk or for making ice cream and custard, and ice boxes were introduced in the evolving Bengali kitchen. Kiranlekha Ray in Jalkhabar [Snacks] (1924) mentioned an array of cookware such as patty pans, pie dishes and cake moulds.[12]

Material forms are intricately related to the organisation of any enclosed space. The traditional Bengali kitchen was bound to change with the inclusion of such new utensils and stoves. The nineteenth century saw the provision of various goods that made European cooking easy in colonial Bengal. By the twentieth century new or foreign food items and appliances were manufactured and marketed by Indian companies in Lucknow, Delhi, Dumdum and Calcutta.[13] The practice of modernity became a quotidian affair through the commercialisation of cookbooks and the ready availability of ingredients as well as equipment in the market. Since many of these were produced on a large scale, their prices became quite low. As a result, new food such as tea could be consumed even by those at the lower rungs of the social ladder. Lila Majumdar’s, Rannar Boi [Cookery Book] (1979) written in collaboration with Kamala Chattopadhyay, insisted that the cook adapt to their times. This was especially relevant to make cooking convenient for women juggling a variety of roles, both at home and outside. Recipes in her cookbook were preceded with an elaborate commentary on appliances, utensils, types of fuels and household tips to make managing the kitchen time-efficient and economical. She mentions the use of the indigenously manufactured smokeless Janta stove that produced a flame in a downdraft mode, reducing health hazards for women working in the kitchen. Majumdar also advocated the use of steam cookers and double-door box ovens to minimise labour in the kitchen. She suggested the use of ceramic, glass, stone, stainless steel and hindalium cookware over kansa and aluminium.[14] Such farsightedness makes her work relevant over time.

Discussions surrounding the organisation of the kitchen, the use of appliances and utensils became an important part of Bengali advice literature. Cookbooks incorporated such instructions following an image of ideal culinary setup. Of course, it was a reflection of the new capitalist modernity, played out in their pages, but it also became indicative of the material background of the much-aestheticised stereotype of a woman stirring the ladle in the kitchen.

Notes

[1] Sen, Grihasree, 84–85.

[2] Choudhury, ‘A Palatable Journey through the Pages,’ 24.

[3] Tagore, Mudir Dokan, 66.

[4] Mukhopadhyay, Pak Pranali, 98–100.

[5] Banerjee, ‘The Bonti of Bengal,’ 79.

[6] Banerjee, ‘The Bengali Bonti.’

[7] Banerjee, ‘The Bonti of Bengal,’ 82.

[8] Banerjee, The Hour of the Goddess, 77.

[9] Ananda Bazar Patrika, 260.

[10] Bhattacharya, Adhunik Rannar Boi, 1.

[11] Pragyasundari Devi, Introduction to Amish o Niramish Ahar, 11.

[12] Ray, Jalkhabar, 137–38.

[13] Ray, ‘A Report of the Indian Industrial and Agricultural Exhibition (Calcutta, 1906–07),’ 145.

[14] Majumdar and Chattopadhyay, Introduction to Rannar Boi, 2.

Bibliography

Ananda Bazar Patrika. Sharadiya Ananda Bazar Patrika, September 26, 1944.

Banerjee, Chitrita. ‘The Bonti of Bengal.’ In The Hour of the Goddess: Memories of Women, Food and Ritual in Bengal. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2006.

———. ‘The Bengali Bonti.’ Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies 13, no. 2 (2013). Accessed October 31, 2019. https://gastronomica.org/2013/04/16/the-bengali-bonti/.

Bhattacharya, Sakuntala. Adhunik Rannar Boi. Kolkata: Nirmal Book Agency, 1976.

Choudhury, Ishani. ‘A Palatable Journey through the Pages: Bengali Cookbooks and the "Ideal Kitchen" in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century.’ Global Food History 3, no. 1 (2017).

Devi, Pragyasundari. Amish o Niramish Ahar, vol. 1. Kolkata: Ananda, 1995.

Majumdar, Lila, and Kamala Chattopadhay. Rannar Boi. Kolkata: Ananda, 1979.

Mukhopadhyay, Bipradas. Pak Pranali. Kolkata, 1883.

Ray, Utsa. ‘A Report of the Indian Industrial and Agricultural Exhibition (Calcutta, 1906–07).’ In Culinary Culture in Colonial India: A Cosmopolitan Platter and the Middle-Class. Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Ray, Kiranlekha. Jalkhabar. Edited by Aruna Chattopadhyay. Kolkata: Kallol, 2000.

Sen, Dinesh Chandra. Grihasree. Kolkata, 1915.

Tagore, Rwitendranath. Mudir Dokan. Kolkata, 1919.