Cookbooks have traditionally received limited attention as artefacts of cultural production. Their pragmatic, manual-like nature dupes us into treating them less seriously than they deserve. In the twenty-first century, with every other channel featuring a food show and numerous food blogs and recipes available at just a click on our cell phones, even the utilitarian purpose of a cookbook seems to be challenged. So, why do we need to read and reevaluate the way we think about cookbooks?

One response is that a structured cookbook is, like a finely written narrative, a compelling unit. It introduces the technique of preparing a dish along with providing insight into the associated culture. Cookbooks are essentially the literature of the senses. The narrative of the recipes can reveal complete food ideologies, prejudices and beliefs that shape the aesthetic preferences of a community, hierarchies of social relation and gender role formation, among many others. Thus, we read not only recipes, but how these recipes interact to form a judgement based on taste. And these judgements are deeply rooted in our social origin.

Arguments based on the longevity of a printed cookbook and its permanence are banal. Recipes on printed paper have the same chance of perishing, sooner or later, as their digital counterparts. The organisation of recipes in a cookbook and the intimacy it evokes with its physicality—equally suitable to having by the bedside as to being an accompaniment in the kitchen—make it worth buying and reading.

The flourishing of print in Calcutta during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries ushered the publication of several cookbooks written by women, who utilised this increased interest in the culinary arts to challenge the boundaries between 'home' and 'outside'. Women began publishing a large number of recipes and conceptual debates on their authenticity in various periodicals and newspaper columns. This act of writing recipes from the intimate domain of the household provided a platform for conducting public discussions on healthy, tasteful domestic practices in both material and moral terms. The study of these cookbooks is relevant not only to students of book history but it also helps fill gaps in knowledge about women’s domestic lives that lacks representation.

The printing history of cookbooks in India dates back to the 1800s. Pakrajeshwar, famed to be the first printed cookbook in the subcontinent, was published in 1831. The second edition of this book was financed by the Maharaja of Burdwan, Mahatab Chand, and published with the help of printer-journalist Gaurishankar Bhattacharya. It was 100-pages long, with grand recipes of dishes with tongue-twisting names, and proclamations of the benefits of consuming porcupine, rhinoceros and snake meat. With recipes arranged without proper structure and inadequate attention paid to the details necessary for cookbooks—like the quantities of ingredients—it was wholly unsuitable for middle-class Bengali kitchens.

Pakrajeshwar was followed in 1858 by Byanjan-Ratnakar, also funded by the Maharaja of Burdwan. It had recipes ranging from meat to confectioneries, with generous use of pistachio, saffron, nutmeg, cardamom, cinnamon and clove, befitting a royal kitchen. This book was not for sale but personally distributed by the Maharaja, for which it received limited attention.

In 1879, another book called Pakprabandha, anonymously written, was published. Bipradas Mukhopadhyay’s Soukhin Khady-Pak appeared in 1889. It was published in two volumes, later combined as Pak Pranali. Kalyani Dutta in her meticulous essay, ‘Rannar Boi Prasange’ [About Cookbooks] (1996) wrote about the cookbooks she saw being cheaply sold at Chitpur by peddlers.[1] These books were immensely popular, but had little information about their authors or dates of publication. Randhanbidda [Art of Cooking] was one such book. Dutta also mentioned inexpensive books on miscellaneous subjects written anonymously, which were popularly sold and formed part of Baishnab Charan Basak’s publications. Cookbooks were in the mix of Basak’s bestsellers on chants, sorcery, talismans and totems. They were a part of the easy-selling repertoire. But who authored these cookbooks? Did women write them? How much were they paid?

Pragyasundari Devi’s Amish o Niramish Ahar [Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Cuisine] was the seminal work on food in Bengal written during this time. The first part of the book, dealing solely with making vegetarian dishes, was published initially in two volumes. The first volume, comprising roughly 400 pages, had no date of publication mentioned on its title page when it first came out. The second volume was published in 1902. These two volumes detailed all aspects of maintaining a well-fed and healthy household. They are now combined into a single book with an introduction by Ira Ghosh, Pragyasundari’s granddaughter.

Through Ira Ghosh’s introduction, we learn about Pragyasundari’s involvement in the invention of the indigenous steam cooker called the Icmic Cooker (1910) that is credited to Indumadhab Mallick.[2] Mallick had reportedly offered to take the patent in Pragyasundari’s name, but she had refused. The printing of this book also popularised in Bengal menu cards, or what the author termed kromoni, adding another feather to her cap. The book is so extensive that one can hardly think of a vegetarian dish not mentioned in its pages. It contains more than 80 variations of dal, about 40 different ways for preparing rice, and curious dishes such as inrdal (made by grinding split pigeon peas, red lentils and split chickpeas into a paste) and kavi sangbardhana barfi (sweetmeat made of cauliflower), which was invented by Pragyasundari to commemorate Rabindranath Tagore’s 50th birthday.

The second volume, about 800 pages and dealing with non-vegetarian fare, was published in 1907. Pragyasundari starts with a simple dim bhaja (fried eggs) and dimer sheera (eggs sweetened with powdered sugar) and quickly moves on to nona maacher fufu (salted fish balls), Parisian chechki (parsley cooked with potatoes), pork chops, paper cutlet (mutton chops wrapped in paper and fried), and then to delicacies such as taaler pudding (pudding made with toddy palm). She included several recipes for preparing curries. The recipes sometimes used the curry powder concoction made infamous by the British. But most recipes that end with the word ‘curry’ suggested a different spice blend made entirely from scratch.

This is an eclectic collection, put together cohesively, albeit with some tweaking, for snug placement in middle and upper-middle-class Bengali kitchens. The recipe for note saak bhaji (fried leafy greens) is followed seamlessly by that for tinned salmon cutlet a few pages later.

These cookbooks were landmark publications requiring both time and money. Discussion on food was supplemented with information on the use of unan (mud oven) to create temperatures akin those in Western-style ovens, along with information on the use of various utensils. The need for maintaining hygiene in the kitchen was elaborated on, along with details on proper gutting of meat and rules regarding consumption of food in accordance to the Bengali calendar. Chicken was prohibited for consumption in Magh (January–February), Phalgun (February–March), Choitra (March–April) and Boishakh (April–May) as the birds were more likely to be stricken with disease during these months. Such culinary judgements are a testament to the author’s deep awareness, in contrast to mere superstition. Pragyasundari Devi ingeniously named several dishes after family members—Dwarkanath firnipolau, Surabhi payesh, Rammohun dolma polau, etc. The last dish, an extremely spice heavy rice preparation, was included in her later publication Sankhipto Amish o Niramish Ahar [Abridged Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Cooking] (1918). She wrote one more book, Jarak: Achaar o Chutney [Recipes for Pickles and Chutneys] (1927).

By 1924, Kiranlekha Ray’s Barendra Randhan [Cuisines from North Bengal] and Jalkhabar [Nibbles] was published. Saratchandra Ray, Kiranlekha’s husband, was from Barendra Bhumi, present-day north Bengal in Bangladesh. He was a landlord of Dighapatia, and took keen interest in promoting the regional history of the land.

Bengalis first came to read and hear about cuisines alien to Calcutta and its surroundings through Kirenlekha Ray’s writings. Kirenlekha’s attempt was to document the food history of this region through Barendra Randhan. The book also included recipes she learned during her stay in Varanasi and a few European and Mughlai dishes. It was published posthumously by her husband, who wrote the introduction to the book. Starting with recipes for pora (charred) vegetables, fish and meat, the book goes on to elaborate on preserves, pickles and kebabs. Though the latter is reluctantly tagged as ‘foreign’, an accompanying write-up by Kirenlekha classifies it otherwise. Citing ancient Bhattikavya composed during the seventh century CE, the write-up mentions Lord Rama’s consumption of skewered meat akin to seekh kebabs after offering it to the gods.[3] Kirenlekha also goes on to provide recipes for preparing beef. Pragyasundari Devi in her magnum opus had touched upon the inclusion of beef in the daily diets of Europeans, but quickly asked her readers to switch beef with either goat meat or chicken in the recipes. Kirenlekha had no such reservations. There was no limiting impulse in her writing of recipes that restricted the dietary choices of her intended audience. It is disconcerting to think of the trouble this cookbook, with the blasphemous mention of Rama and meat in the same breath, might have created in today’s climate.

Kirenlekha’s sudden death in 1918 unfortunately ended her endeavour of popularising cuisines from north Bengal. She had written two more cookbooks, Luchi Kachori [Snacks] and Mithai [Sweetmeat].

Binapani Mitra’s Cheleder Tiffin [Tiffin for Children] came out in 1941. Introduced in the book’s cover as ‘Sahitya Saraswati’ (Goddess of Literature), Mitra begins by stating the health benefits of consuming local foods as opposed to ‘foreign food’ such as cakes and biscuits. In the manner of a case study, she tells a story she heard from an old physician in Calcutta: A famous attorney, a relative of this physician, went to a cardiologist in Germany to get treated for his heart condition. The German cardiologist’s breakfast spread, surprisingly, comprised the humble muri (puffed rice), gur (jaggery) and peshai narkel (grated coconut), eaten commonly in rural Bengal. It was supposedly this food that kept him in good shape. Binapani Mitra goes on to provide around a hundred-odd recipes that could be innovatively assembled using inexpensive local produce. Recipes for kacha peper chop (fritters made of green papaya), chine badam barfi (sweetmeat made of peanuts) and ananda laddu (sweet made of coconut, rice flour and sesame) were written with emphasis on their restorative qualities.

Tanuja Devi’s well-appreciated and smallish Panchmishli [Medley] was published in 1949. The introduction to the book was written by Indira Devi Choudhurani, regarded as Rabindranath Tagore’s favourite niece. It includes a replica of Tagore’s handwritten poem appreciating Tanuja Devi’s skill in making the cherished Bengali sweet, sandesh.

Binapani Mitra’s Randhan Sanket [About Cooking] followed in 1955. In the introduction to the book, the author says that the recipes in the book were written much earlier than the date of publication. Mitra concerned herself with the marketability of her book. She made it clear that the cookbook was written not only to further discussion on good food, but also to reap profit. Owing to the apprehension that cookbooks dealing solely with vegetarian fare did not sell as many copies, she included non-vegetarian dishes. Complicated recipes—especially those involving moulding dough, such as puffs or Dhakai jilepi (a speciality dessert from Bangladesh)—had accompanying images, simplifying things for her readers. Mitra’s book was specifically planned to indoctrinate new cooks into the kitchen. Thus, it focussed on bringing together a collection that would be plain sailing and of daily use.

Snehalata Devi’s Achaar o Morobba [Pickles and Preserves] was also circulating in the market during this period. This book makes no mention of its date of publication, a practice not uncommon at the time. Its introduction was written by renowned Bengali writer Premendra Mitra, who enthusiastically endorsed the literary pleasure of reading this book that was as capable of making an aesthetic impression as any work of art. The book also emphasises the technicalities or, rather, the chemistry, of making the preserves and pickles, which Snehalata Devi simplified for her readers along with the recipes. Divided into 10 chapters, the book provided several methods for making jams, jellies, pickles and preserves. Two pages were also devoted to the preparation of lime cordial and gulkand (candied rose petals), disregarding their separate categorisation.

Purnima Tagore in 1985 brought out Thakur Barir Ranna [Foods from the Tagore Kitchen], which had several editions, the latest in 2016. This book is mostly an assemblage of hand-written recipes by Indira Devi Choudhurani, with celebrated dishes from the Tagore family kitchen such as mowrola maacher ambal (fish in green tamarind puree) and egg chou chou (eggs cooked with spices). The author also included a few of her own recipes, providing insight into the culinary innovations of the kitchens of the Tagore family.

Renuka Devi Chaudhurani’s well-received work on Bengali food, Rakamari Niramish Ranna, was published in 1988, and Rakamari Amish Ranna followed. An abridged version of these classics, Pumpkin Flower Fritters, was published in 2008, and was translated into English by her daughter-in-law Sheila Lahiri-Choudhury. The two volumes contain selections of over 700 vegetarian and non-vegetarian recipes, along with household tips.

Married off at the age of 10 into a conservative zamindar family, Renuka Devi came to live in Muktagachha, Mymensingh district of East Bengal in present-day Bangladesh, and began collecting recipes from family and friends. The book is steeped in the period’s rich cultural context. In her splendid introduction, ‘Amaar Katha’ [My Story], she speaks of the varied influences and instances that dotted her life—from her initiation into the art of cooking by her father-in-law Raja Jagat Kishore Choudhury (lovingly called kartadada) and the influence of Pragyasundari Devi’s and Kirenlekha Ray’s cookbooks to lessons from their revered family-cook Noora Baburchi (referred to as Noora Chakravarty in the pay register of the estate).

Apart from the usual rice, dal, sukto (vegetables in a bitter gravy), chhenchki (lightly fired mixed vegetables), ghanto (spicy mixed vegetables) and chutney, the book contains delicate recipes for making fritters out of jasmine and jute leaves, and water hyacinths, mustard and drumstick flowers. The second volume has a section instructing in the preparation of game meat. The recipes were written at a time when game laws were not stringent and venison was available in the market. A spread of hariner mangsher chonga kebab (venison cooked in bamboo) or a stuffed green pigeon on tables was not uncommon.

Renuka Devi, however, makes little allowance for a novice’s unfamiliarity with measurement of ingredients, and leaves a great deal to the cook’s andaz (judgement). The two volumes nonetheless are a celebration of the author’s enthusiasm for the culinary arts that could have been easily reduced to drudgery.

The latter half of twentieth century saw a slew of women cookbook authors, including Sadhana Mukhopadhyay, Bela Dey, Sanchita De and Nandita Chatterji. Though all of them produced extensive works, it would be grossly erroneous to club them together. Bela Dey became a brand name, only comparable to the phenomenon of Mrs Beeton, the famous Victorian proliferator of all things quotidian. Very little though is known about her life. With a distinctly affable voice, she was a presenter of the popular radio programme ‘Mahila Mahal’ for All India Radio (AIR) and the writer of ‘Sukhi Grihakon’ [Happy Household], a column for the Bengali daily Bartaman.

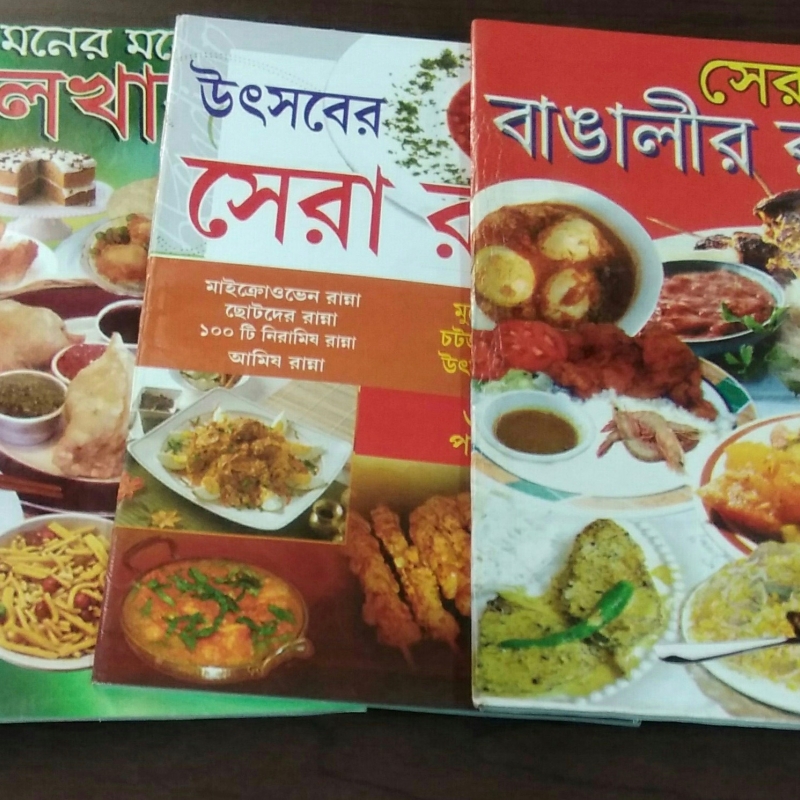

Dey wrote a plethora of inexpensively produced cookbooks such as Ranna Banna [To Cook] (1982), Hajar ek Ranna [Thousand and One Recipes], Sera Bangali Ranna [Ultimate Bengali Food] and Moner Moton Jalkhabar [Favourite Snacks], which still sell at railway book stalls. Most of these books were published without a date. Dey was a household name because of her AIR programme, which helped sell her cookbooks. Perhaps it was due to this popularity that her works were heavily pirated. Written for easy comprehensibility, and often lightweight like chapbooks, they targeted a wider demography of people at various levels of the social order. Their aim was to make cooking less time-consuming as well as to add variations to the Bengali palate. There is no censorious eye lurking to admonish the use of store-bought spice mix or any indignity in writing ‘pomplate’[4] instead of pomfret, commonly mispronounced in Bengal. Even the measurements of ingredients were in cups or spoons to make them easy to follow. Amidst horde of cookbook publications that come out with her name every year, it is hard to know when she actually stopped writing.

Coming close to Bela Dey’s appeal is Sadhana Mukhopadhay. Apart from writing several cookbooks such as Maach Ranna [Cooking Fish] (1986), Ghoroa Ranna [Domestic Cooking], Niramish Ranna [Vegetarian Cooking] and Jam Jelly, she also wrote for periodicals and newspaper columns.

Around this time, a thin, unimaginatively titled Rannar Boi [Cookbook] (1979) also made a mark. It was written by Bengal’s leading writer of children’s fiction, Lila Majumdar, with her daughter Kamala Chattopadhyay. The book had several reprints and it is still in circulation. Majumdar believed that women have a larger role to play in society. One’s personal and political lives could co-exist with skilful managing of the kitchen, which formed the centre of a household. The book is filled with tips and shortcuts to expedite the process of cooking, while advocating for frugality in our food practices.

Divided into 10 sections—soups, bread and rice, lentils, vegetarian fare, eggs, fish, meats, desserts, restorative diet for convalescents, and a segment on hospitality food—the recipes show their adaptability to time, along with an openness towards different culinary influences and traditions; the recipes in Rannar Boi were inspired by Anglo-Indian, Chinese and Muslim settlers in Kolkata. So, we have dishes such as Chinese omelette made by beating eggs and noodles, placed with the whimsically coined begun puri, made by cooking aubergines and small mutton pieces together.

These recipes resonate with the voice of their author. Through this rhetoric over food, a dramatic reshaping and reappropriation of women’s agency is reflected. Revisiting these works makes possible a more textured understanding of women’s role, both in private and public sphere.

Women-authored cookbooks have been instrumental in defining as well as breaking notions about womanhood and domesticity, along with informing middle-class culture, economy and industry. They are crucial to the discourse of women’s history in Bengal.

Notes

[1] Dutta, ‘Rannar Boi Prasange.’

[2] Devi, Introduction to Amish o Niramish Ahar, 3.

[3] Ray, Barendra Randhan, 55.

[4] Dey, Hajar ek Ranna, 59.

Bibliography

Achaya, K.T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Banerji, Chitrita. The Hour of the Goddess: Memories of Women, Food and Ritual in Bengal. Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2001.

———. Life and Food in Bengal. Noida: Rupa & Co, 1993.

Chatterjee, Partha. Nation and its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Choudhurani, Renuka Devi. Pumpkin Flower Fritters: And other Classic Recipes from a Bengali Kitchen. Translated by Sheila Lahiri-Choudhury. New Delhi: Black Kite, 2008.

———. Rakamari Niramish Ranna. India: Penguin books, 2013.

———. Rakamari Amish Ranna. India: Penguin books, 2013.

Devi, Pragyasundari. Amish o Niramish Ahar vol. 1. Kolkata: Ananda, 1995.

———. Amish o Niramish Ahar vol. 2. Kolkata: Ananda, 2000.

———. Jarak: Achar o Chutney. Kolkata: Ananda, 1995.

Dey, Bela. Grihinir Abhidhan. Kolkata: Patraj Publication, 1978.

———. Hajar ek Ranna. Kolkata: Sajal Publishers.

Dutta, Kalyani. ‘Rannar Boi Prasange.’ In Samaj, Sanskriti, Nari-I, Pinjare Bashiya. Kolkata: Stree, 1996.

———.Thod Bodi Khada. Kolkata: Thema, 1992.

Kabibhushan, Pyarimohan, ed. Pakprabandha. Kolkata, 1934.

Majumdar, Lila, and Kamala Chattopadhay. Rannar Boi. Kolkata: Ananda, 1979.

Mitra, Binapani. Cheleder Tiffin. Kolkata: Dasgupta & Co, 1941.

———. Randhan Sanket. Kolkata: Sri Somya Mitra, 1970.

Mukhopadhyay, Bipradas. Pak Pranali. Kolkata: Ananda, 2000.

Mukhapadhyay, Sadhana. Mach Ranna. Kolkata, 1986.

———. Phelachhdar Ranna. Kolkata: Ananda, 1987.

Ray, Kiranlekha. Barendra Randhan. Kolkata: Bijay Kumar Moitra, 1921.

Ray, Utsa. Culinary Culture in Colonial India: A Cosmopolitan Platter and the Middle-Class. Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Sen, Manimala. Pitha Puli Payas. Kolkata: Proyash, 1997.

Tagore, Purnima. Thakur Barir Ranna Banna. Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, 1986.

Sri Pantho, ed. Pakrajeswar o Byanjan-Ratnakar. Kolkata: Subarnarekha, 2004.