In 1946, A.V. Meiyappan, the founder of AVM Studios, travelled to Karaikudi with a 12-year-old boy named R. Parameswaran, who was to join as an assistant at his new film studio there. Karaikudi, 400 km southwest of what was then Madras, was Meiyappan’s hometown.

By this time, Meiyappan had already completed his first directorial venture, Sabapathy (1942), which was filmed in his one-floor studio in Adyar, Madras, with second-hand equipment. The threat of the Japanese bombing Madras during the Second World War along with the restricted power supply for film studios led him to shift to Karaikudi.

As a young assistant, Parameswaran, originally from Kerala, watched film reels being developed for the first time in the studio in Karaikudi. He joined the hand-laboratory there as an assistant printer in 1947. For the next 71 years—until 2018—he would be immersed in the workings of AVM's black-and-white cine lab at AVM Studios, and witness a large range of changes triggered by technological shifts.

When Parameswaran started out at the hand-laboratory at Karaikudi, the rack and tank system was being deployed for processing and developing films. As soon as the film was shot, 350 feet of the exposed film would be quickly wound up in a rack—a round frame or drum of sorts. Following this, the film was hand-developed in special tanks with chemicals. The developer would keep an eye on the proper density of the image. Once developed, the wet film roll was hung to dry on racks. The printers of the early days were hand-operated as well, and exposure control was difficult and required a great deal of skill.

While based in Karaikudi, AVM Studios produced Naam Iruvar (1947) and Vedhala Ulagam (1948), two seminal films with manually coloured sequences. An extraordinary craftsman named Murugesan worked on these films, painting each frame of a positive print (a final print of the film made from a negative or inter-negative print for release and screening purposes). Murugesan’s sequences of these two films fascinated filmgoers at the time.

The hits produced at the Karaikudi Studios made the landlord double the rent. This, coupled with the lifting of the ban on electricity in Madras, made Meiyappan shift the studio complex back to Madras and set it up in the neighbourhood of Kodambakkam in 1949.

AVM Cine Lab’s trajectory deeply influenced and ran parallel to that of the man who had worked there from its inception. In September 2018, nine months after the cine lab at AVM Studios was shut down, I had a long conversation with Parameswaran in the printing room in the lab. Parameswaran wore dark glasses to protect his weak eyes and frowned as he tried to remember precisely the long history of the machines; sometimes he seemed stupefied by the decision to scrap these historical machines or sell them for metal, at other times he chuckled at the inevitable reevaluation of all things. While recounting anecdotes, Parameswaran found his way around the moist and dimly lit corridors leading to the abandoned laboratory with ease.

A researcher’s reconstruction of the black-and-white lab’s history is akin to documenting oral folklore. One assumes the years are sometimes only approximate, but the astoundingly sharp recollections of a man who has spent his entire life working closely with the material medium of cinema, verified against written documents and archival information, gives the story a lot of credence.

The 1940s, 50s and early 60s were the golden era for studios in Madras, with seminal films being shot in the studio spaces and many prints developed, processed and prepared for distribution in the labs. The first film to be produced from the AVM’s Kodambakkam studio was Vazhkai (1949), and over the next two decades, path-breaking productions such as Ore Iravu (1951), Parasakthi (1952) and Andha Naal (1954) were to follow.

By 1950, Parameswaran had already become the main printer at the lab. The first semi-automatic printing machine came into the AVM Cine Lab in Madras in the early 1950s—an American Bell and Howell manufactured in 1947 (Fig. 1). Film Centre in Tardeo, Bombay, often imported motion-picture equipment from abroad and distributed it within India, and AVM Cine Lab started getting second-hand machines from there.

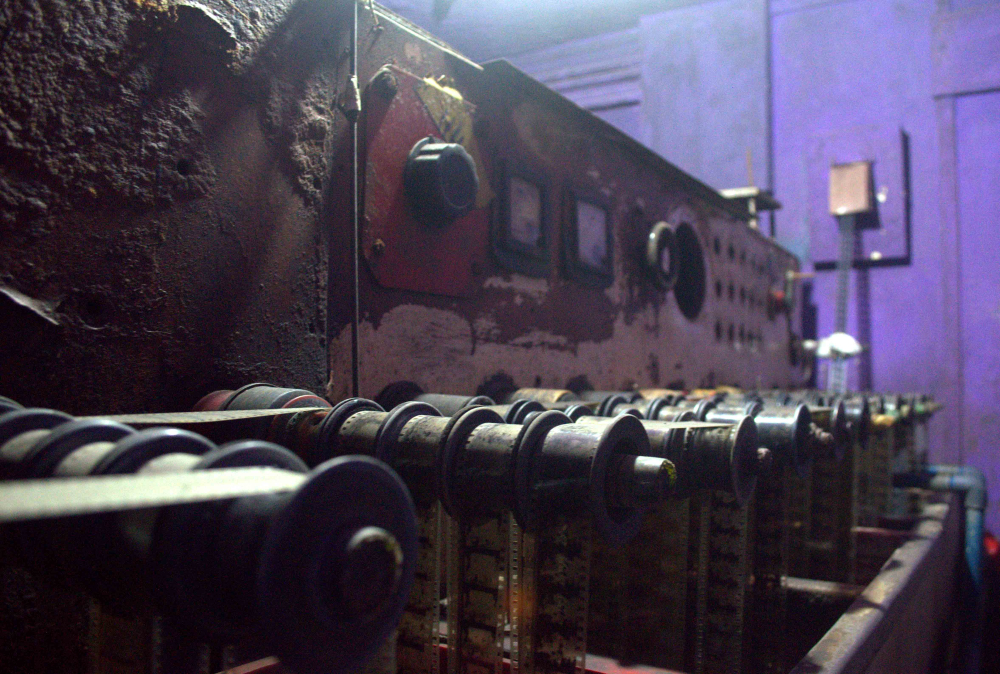

When I met Parameswaran in 2017, he was demonstrating the working of the American printer to a group of young celluloid-preservation enthusiasts. One could hear water running in the next room—an earlier reel of film was being washed and developed in a big chemical bath, part of the Arri developing machine (Fig. 2). Images were gaining clarity and capturing the photo-sensitive emulsion as they passed through the different chambers of the chemical wash. A whirring sound from the drying chamber complemented the sound of film running through water. The cold metal machine at the centre of the room was shining in the dark laboratory, where Parameswaran’s fingers, moving swiftly but shakily, passed film through sprockets.

AVM acquired machines for processing and developing films in the early 1950s, and the hand laboratory then moved on to more efficient methods. During this decade, Parameswaran moved from being the printer to working with print-checking and grading. In the 1960s, he was made the lab-in-charge. With a meagre salary that was not going to improve much, and a great deal of responsibility, he held the reins of the cinema lab at AVM Studios. The film studio, like other factories, had its own labour union fighting for fair wages and other issues. By the late 1960s, Parameswaran became one of the communist leaders of the trade union overseeing several film labs. Around this time, Meiyappan offered him the position of partner at AVM’s lab. He promptly turned it down, as he was clear that this position would not garner him popularity with the other workers.

In the black-and-white era, many other studios in Madras—including Vasu, Majestic, Ratna and Newtone—had their own laboratories, but the most prominent ones in the business were AVM, B.N. Reddy’s studio and Vijaya Vauhini. This status quo changed after the arrival of colour. S.S. Vassan’s Gemini Studios (Fig. 3), founded in 1940, set up its colour lab in 1958. Prasad Studios was soon to follow suit. The land that AVM Studios was built on was a leather tannery that was left vacant after Partition, Parameswaran recalled. The water of the neighbourhood was harsh, full of chemicals, and not conducive to colour printing. Prasad Studios started the first modern additive colour lab using treated water, but AVM decided against it. Gemini and Prasad were already in the business of colour printing. AVM Studios could not anticipate cinema completely shifting to colour, and despite its early experiments in hand-printed sequences, the studio did not upgrade their laboratory with the changing times. Though the decision to stick to black-and-white made it a one-of-a-kind laboratory, it had major repercussions for AVM’s future.

Around two years before the first colour laboratory was set up, the State Re-organisation Act of 1956 reevaluated and divided Indian states along linguistic lines, which made many films in other southern languages, including Telugu, Kannada and some Malayalam films, gradually move out of Madras studios to Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala, respectively. These shifts were a heavy blow for the black-and-white cinema laboratory at AVM.

In 1956, Modern Theatres released the first full-length colour film, Alibabavum 40 Thirudargalum, in Tamil, an exploration of the fantasy genre through this new technology. This film was shot on Gevacolor, a colour process for moving images, which was an affiliate of Agfacolor that had been established in Belgium in the late 1940s. Gevacolor was primarily used by Madras Film Studios in the late 1950s and early 1960s to shoot films with partially coloured sequences. However, it failed to take over the market in a substantial way, and only a handful of films were partially shot using this colour process.

With the introduction of Technicolor, a more expensive process, more producers took notice of this inevitable and tremendous shift in technology but could not afford it. In 1959, Veerapandiya Kattabomman was the first film to have been shot in Gevacolor and then partially printed in Technicolor in Germany. In the early 1960s, another expensive colour process called the Eastmancolor was introduced, which also garnered very few productions. Most films with middling and small budgets in Madras continued to be shot in black-and-white through the 1960s and early 1970s, which worked to the advantage of the AVM Cine Lab. The introduction of affordable Orwo colour in the 1970s led Madras studios to take a distinct turn. Most films in the 1980s were shot in colour, using Orwo, and this was the point from where AVM Cine Lab attempted to find its unique sustenance, despite having fallen out of the market. (Fig. 4)

The other major technological change that affected the cinema laboratory was the advent of television. The first one-hour daily news programme was introduced in the 1960s. Available only in Delhi during that decade, television services arrived in Mumbai in 1972, and in 1975 they were extended to Madras. It initially did not pose a threat to the cinema laboratory—operating only in seven cities and a handful of households, it did not seem likely that television would supersede the cinematic medium. In 1976, television separated from AIR and started finding its own ground. Shortly after, Doordarshan became a national broadcaster and the ’80s witnessed the rising popularity of television among urban audiences. In 1982, Doordarshan started telecasting national programmes and in colour; the popularity of these got the audience of the moving image hooked on to TV sets. AVM Productions attempted two television serials in the latter half of the 1980s, namely Our Manithanin Kathai (1986) and Netraya Manithargal (1988) but only plunged into making television soaps in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

During a long conversation with N. Ramesh, Parameswaran’s assistant from the final years, he reminisced about what 16 mm screenings came to mean for the AVM Cine lab during the 1980s[1]. At this time, 16 mm was a very popular low-budget film gauge used for amateur films, industrial videos, home movies, etc. One of the main projects that kept the film lab occupied was printing economical 16 mm gauge films for screening purposes. Often shunned as substandard by the professional industry till it was given a fresh lease of life by documentary filmmakers, 16 mm was an easy way to screen films—in villages and suburbs, fairs and private screenings, and events outside of the commercial cinema hall—without running into authorisation issues with the producers. Ramesh and Parameswaran, inspired by how AVM Cine Lab continued to reprint 35 mm films in 16 mm film format, tried to set up a film lab of their own to only produce 16 mm screening prints. Often a 16 mm positive print would be directly printed down from a 35 mm print to cut costs, as this would be for budget printing projects only for screening at a village fair or festival. Parameswaran’s team was printing cost-intensive 16 mm versions of older films for cheaply ticketed screenings for local markets and for large crowds through the 1980s, as permission taxes were not required for these copies.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, older black-and-white cinema was screened on television and prints needed to be made for this purpose. The cine lab often used to make new prints for the Telecine process, where motion-picture film stock was transferred into video format for television distribution. Reprinting older films was also carried out for the theatrical re-releases attempted by producers and rights owners. This trend of re-releasing older black-and-white films spilled over into the early 1990s. The triumph of TV through the 1990s gradually killed the prospect of commercial re-releases of old films in theatres, as the TV industry was in business with the rights owners.

Parameswaran retired from AVM Cine Lab briefly in the 1990s to start the independent laboratory with some partners, including N. Ramesh. With second-hand machines acquired from Vasu Studios, the team was confident about carrying on business with 16 mm screening prints. Various printing and developing machines at the AVM Lab were junked around this time; machines that formed the cornerstone of the cinematic world were scrapped and sold for metal. In 1979, when Meiyappan passed away, two of his sons, Sarvanan and Balasubramanian, took over AVM Productions, while another son Murugan inherited the cine lab. It was the latter who requested Parameswaran to return to the laboratory to take on archival work in the early 2000s. Parameswaran brought the second-hand Bell and Howell printing machine acquired from Vasu Studios to the laboratory, as the lab’s older printer was already scrapped by then. The early 2000s were difficult, as the laboratory started becoming solely dependent on archival work sourced from the National Film Archives of India (NFAI), Pune. Barely sustained by the scanty work coming in from the NFAI (which involved reprinting films for archival and private screenings), the laboratory’s staff diminished substantially. Until late 2018, the laboratory office had stray cans of raw stock lying around, the remnants of archival projects that had fallen through (Fig. 5).

In November 2019, Parameswaran grieved over the final moment in the life of AVM Cine Lab in a telephonic conversation with me: all the machines belonging to it were tossed out as the laboratory space has been sold to an office.[2] A group of three young documentary filmmakers from Bangalore had expressed interest in taking the printing machine. Some machines were sold as scrap for metal, others scattered haphazardly across people’s personal collections. Although the office of the production house keeps several machines that were used during film production in the past, the likelihood of researching and documenting the important history of cinema technology appears to be dwindling.