In cinema-crazed Chennai, every street has political graffiti with film stars and film posters. The billboards, flexes and cutouts of fabled film stars, often freshly garlanded, evoke open-air temples.

Cinematic references are inescapable around the city; signboards invoke memories of renowned studios after which several streets and institutions are named—Arunachalam Street, Forum Vijaya Mall, Vijaya Hospital, Bharani Apartments and others. People stream in and out of shops, apartments and hospitals, mostly impervious to the cinematic history that infuses these spaces. Like the memory of a dream, fragments of celluloid speck the contemporary film-watcher’s mind. An old security guard at Prasad Studios and an older man serving idlis in a café reminisce about a time when their lives were immersed in the celluloid industry.

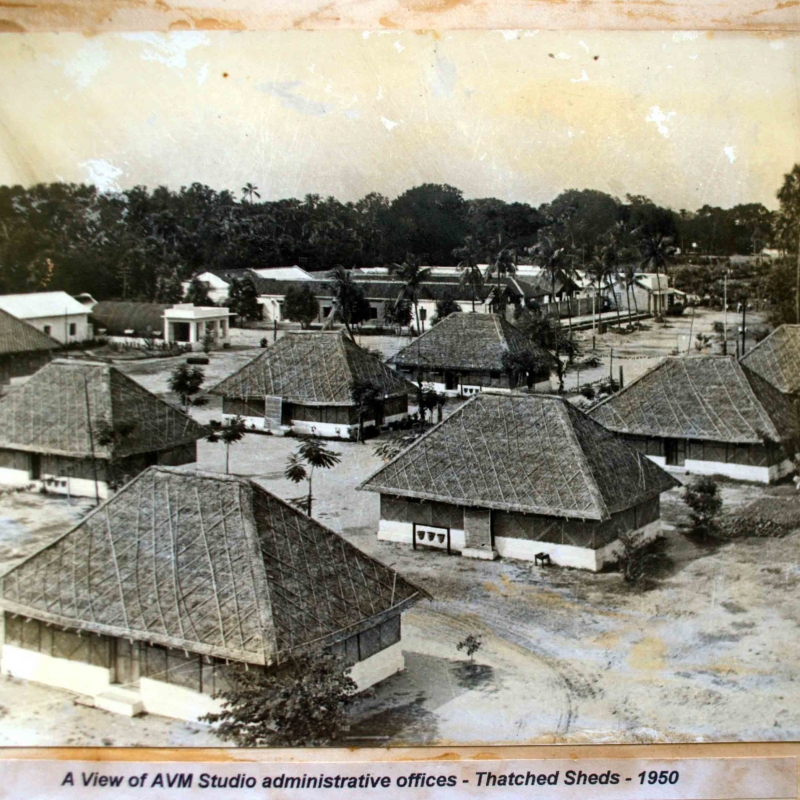

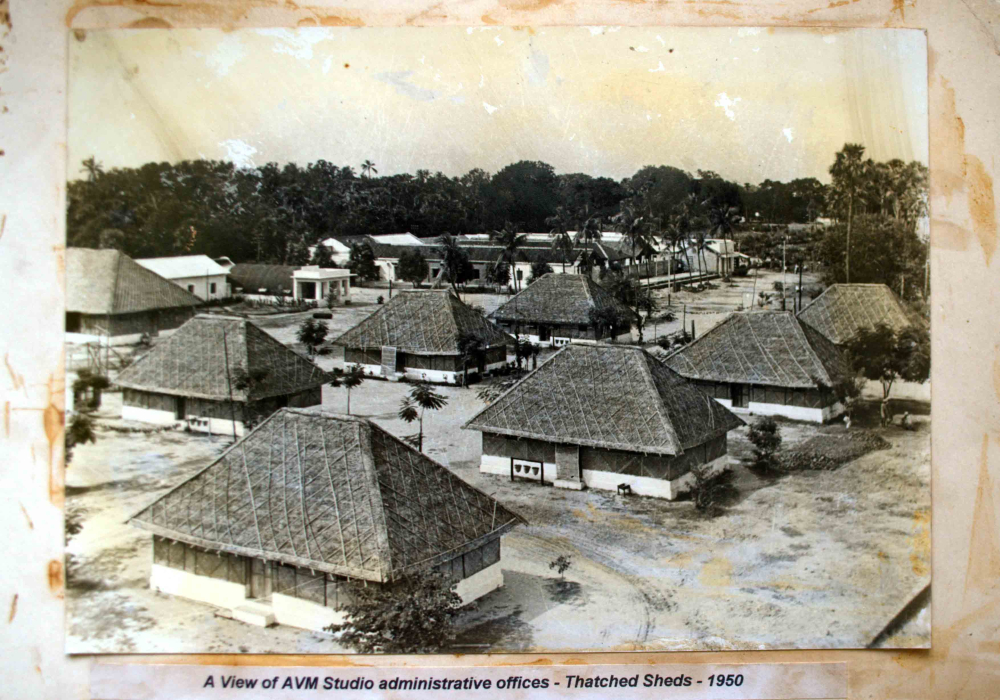

The neighbourhood of Kodambakkam, where the famous AVM Studios—one of the earliest studios in the country, built in 1949—once stood, provides clues to and fragments of cinematic history. The contemporary flexes and banners bear testament to this obscured layer of history, otherwise unseen on these streets.

Kodambakkam became central to the film industry (colloquially dubbed ‘Kollywood’ after the neighbourhood) after numerous other studios imitated AVM’s formation. On Arcot Road, Vadapalani, one cannot miss the AVM Studios globe rotating squeakily while foregrounding a high-rise owned by part of the family.

Mohan Raman, an actor and city historian working closely with the history of Chennai studios, claims that, contrary to popular belief, the first studio in Kodambakkam was Star Combines by A. Ramayya in 1946. Two years later, B.N. Reddy set up his Vijaya-Vauhini Studios in the neighbourhood. AVM came to the neighbourhood only in 1949. But the story of AVM Studios starts long before studios came to this neighbourhood.

Birth of a Studio: From Gramophones to Moving Images

A.V. Meiyappan (Fig. 1), the eponymous founder of AVM Studios, was from Karaikudi, 400 km southwest of Chennai. His father, Avichi Chettiar, had a shop called A.V. & Sons that sold utility items, where the first image-making apparatus made its entry when he started selling Kodak films. It was through gramophone records that the family steadily approached the world of recorded images. By the time A.V. Meiyappan took charge of this store, it was already selling gramophone records. It had begun distributing for HMV and Columbia, the major manufacturers of gramophone records for Madurai, Tiruchi, Ramanathapuram and Tirunelveli districts in the 1920s. Meiyappan, who had already realised the potential of the gramophone industry, was keen to get involved with the business.

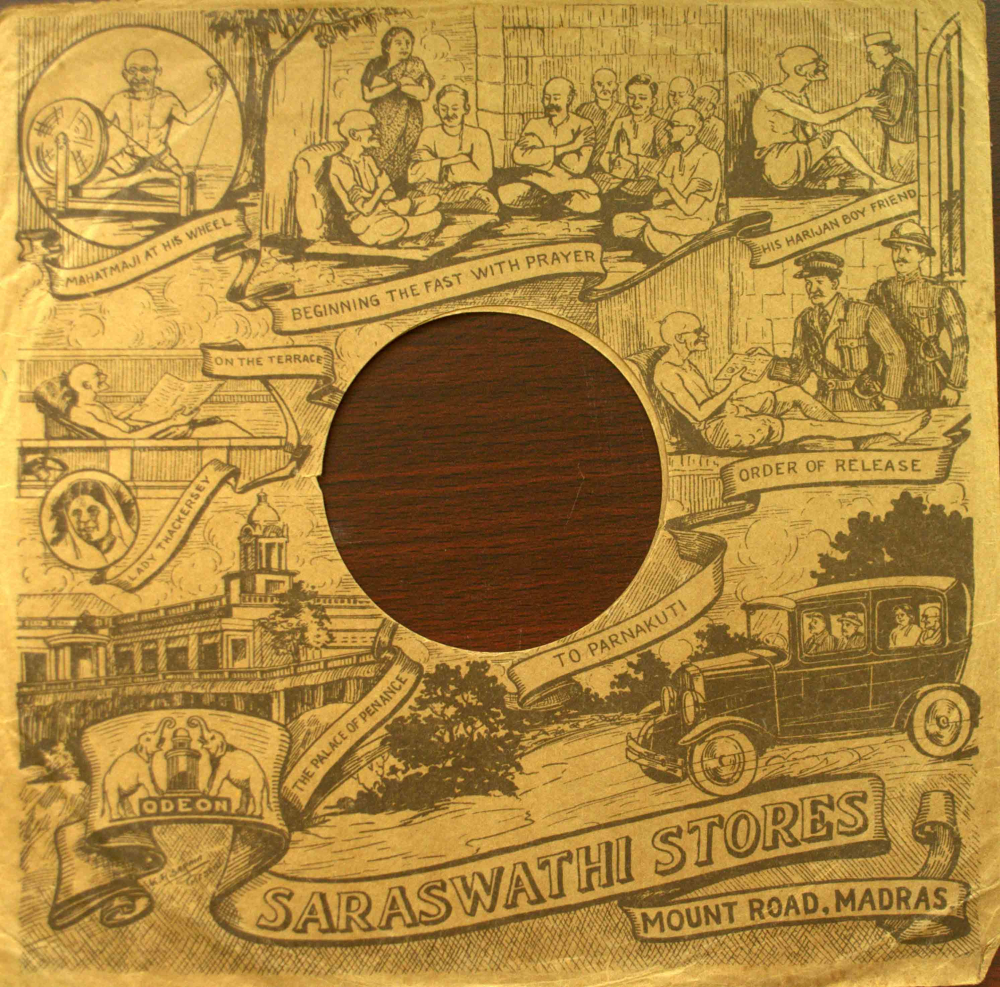

In 1932, he visited Madras and partnered with Narayana Iyengar and Sivan Chettiar to set up Saraswathi Stores on Mount Road. Here the visionary businessman decided to produce recorded songs and plays, both highbrow and popular, in Tamil Nadu. Gramophone record companies at the time were, like other elitist cultural institutions, protected by a powerful Brahmin community that looked down upon folk and theatre music. Meiyappan, however, was astute enough to gauge the potential of recording the tremendously popular songs of theatre artists who were performing folk-inspired semi-classical forms of music. His decision to produce popular or folk songs alongside classical ones eventually led to his cinematic venture.

In 1934, Saraswathi Stores started releasing records of songs from popular plays. Their unprecedented success led Meiyappan to release two ‘drama record sets’ of the Hindu epic Ramayana and ‘Kovalan’, a story from the Tamil epic Silappatikaram (Fig. 2). Meiyappan’s decision to enter into a contract with the German gramophone company Odeon brought about groundbreaking shifts in both technology and popular culture. Recorded sound on wax was exported to Germany from where multiple 78 RPM shellac records were imported to Madras, as Chennai was then known, for large-scale local distribution.

By this time, Meiyappan had started Saraswathi Sound Production, a new film-production company, later known as Saraswathi Talkie Producing Company. Madras did not have any studio facilities at the time, forcing Meiyappan to shoot his first film Alli Arjuna (1935) at New Theatres Studios in Calcutta. Meiyappan’s autobiography, My Experiences in Life, recounts how the first film landed them with huge losses; while screening it they realised that the actor had acted with his eyes almost entirely shut because of the bright lights of the film sets.

Rathnavali, Meiyappan’s second film, was also filmed in Calcutta. His third film, Nandakumar, was filmed in Pune, which was rapidly becoming renowned for its studios. Despite Nandakumar being a failure at the box office, it was through this film that the veteran of the gramophone industry and his crew introduced playback technology in Tamil cinema (a move that was decided upon because one of the actors could not sing).[1] The film’s recorded songs were hugely successful, and soon after Meiyappan and his crew would also bring about the first experiments in post-synchronisation and dubbing.

Notwithstanding the box office failures of his early films, Meiyappan set up Pragati Pictures Pvt. Ltd in Bangalore. His first studio was also set up in Bangalore during the Second World War, which delayed the imports of studio equipment from Europe. In the meantime, Meiyappan’s partnership with Narayana Iyengar for Saraswathi Stores had ended. Reluctant to abandon Saraswathi Stores and settle in Bangalore, Meiyappan decided to shift the studio close to Adyar in Madras, and chose the Vijayanagar Fort (later known as Admiralty House) as the new site. This studio had one floor and except for a new recording machine, Meiyappan only bought used equipment.

The Telugu film Boo Kailash (1941) became Meiyappans first big hit. Boo Kailash provides insights into the history of the studio and the history of Madras State (which, formed in 1950, included the whole of present-day Tamil Nadu, coastal Andhra, Rayalaseema, the Malabar region of north Kerala and Bellary, and south Canara and Udupi districts of Karnataka). The movie illustrates the workings of the Tamil studio system in the 40s: the language of the film was Telugu, the producers were Tamil, the director was Marathi, and the actors were Kannadigas. Through the 1940s, 50s and early 60s, Madras was the centre of cinema for all southern Indian languages. Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada films were all produced in the city.

After the States Re-organisation Act of 1956, Madras State was broken up along linguistic lines, and C.N. Annadurai’s government named it Tamil Nadu in 1968. This moment is seen to coincide with most of the other languages moving out of Chennai film industry and finding their own locus. This event delivered the first crack in the Chennai studio system.

Years of the War: Shortages and Regulations Lead to a Shift in Location

After the success of his first directorial venture, Sabapathy (1942), Meiyappan had to return to Karaikudi as there was a severe threat of the Japanese bombing Madras during the Second World War.[2]

The war had a far-reaching impact on cinema as the movement of film equipment, electricity for studios and raw stock were strictly controlled. For example, Meiyappan’s Harishchandra in 1943 faced wartime regulation on raw stock, which was reserved for propaganda films. This resulted in the edited length of the film being restricted to 11,000 ft—half the usual length of Tamil films of the time, which, drawing directly from theatre, hosted around 50 songs as part of the narrative. The audience appreciated the concise format of Harishchandra. It was a huge success and inspired the sound department to experiment with dubbing (innovators in the industry dubbed the original Kannada film in Tamil), a decision that engendered yet another turning point in Tamil cinema.

The repercussions of the War had restricted power supplies, and the electricity department was unable to set up power at a new studio. In Karaikudi though, power supply was in the hands of a private company called the Meenatchi Sundareshwarar Corporation, and this caught Meiyappan’s attention.

Around the same time, Somanathan Chettiar, a zamindar of Devakottai, had laid a road from Devakottai to Karaikudi and opened a railway station there. To popularise this station, he also went on to build a drama theatre nearby. Meiyappan, already deeply involved in the associative correspondence between the mediums of theatre and cinema, could think of no better space to build his film studio. Tying together the railways, drama theatre and the studio system, Meiyappan set up close to 50 thatched sheds in this venue. The two big wooden posts of the drama theatre showed up in his films as part of the mise en scène as the mediums spoke fondly to and of each other. He named this space AVM Studios (Fig. 3).

In his autobiography, A.V.M Speaks, Meiyappan uses the word ‘factory’ to describe the studio space and the filmmaking process—a revealing turn of phrase, because filmmaking followed a meticulous production process like any other factory and had a division of labour. Studios were industrial complexes with machines, buildings and salaried employees who oversaw every aspect of filmmaking, including pre-production, production, distribution and exhibition.

During the late 40s, theatre was independently changing towards a more social genre. Cinema was preparing to break out of the mythological and devotional genres as well. A social play called Naam Iruvar, staged by NSK Nataka Sabha, catered to the patriotic zeal of people around the time of Independence, with the wartime ‘black market’ forming its backdrop. The playwright P. Neelakantan sold the rights for Rs 3,000 to Meiyappan and agreed to come on board as an assistant director adapting his play for cinema.

Subramania Bharathy, famously known as Bharathiyar, was a fiery Tamil poet, independence activist and social reformer whose nationalist songs formed the backbone of the play. During the making of the film, the gramophone recording company Surajmal and Sons owned the copyright to many of Bharathiyar’s songs, which Meiyappan managed to buy for Rs 10,000. In a peculiar transaction, Meiyappan came to privately own Bharathiyar’s songs and restricted the use of them by others. Bharathiyar’s songs found a life of their own after Independence, and print media, radio and theatre were replete with lyrics from these songs; this led to Meiyappan handing over ownership of Bharathiyar’s songs to the government, and the songs were eventually made public property. Film songs in Tamil cinema went on to be a fiercely wielded political tool, and Bharathiyar’s songs in Naam Iruvar were among the earliest examples of songs in an Indian movie playing such a phenomenal role in uniting people for a sociopolitical cause. The dialogues of the film were interspersed with political slogans and visuals along with photographs of freedom fighters. Naam Iruvar was also the first film under the AVM banner. Meiyappan claims in his autobiography that this film brought a change in the audience in that they were now ready to witness social narratives in cinema.[3] The studio continued to prioritise songs as having a life independent of film, as concise narratives often critiquing or praising social and political changes.

The sweeping hits produced by AVM led the landlord to more than triple the rent for the studio, coupled with the lifting of the ban on electricity in Madras in late 1948 made Meiyappan consider shifting back to the city. By then, it was also proving difficult for him to send his canned films to Madras for processing. In 1949, AVM moved to the neighbourhood of Kodambakkam, which would soon be populated with film studios. Meiyappan came upon a 10-acre plot that had belonged to a Muslim owner of a leather warehouse and was vacant after Partition. This time, he introduced two new things to the AVM Studios, a projection or preview theatre and a black-and-white cine lab, which was around till 2017.

The Rise and Fall of Studio Cinema—Arrival of Television, Colour Film Stock, Lighter Cameras

Between the 50s and the 70s, a plethora of studios came up in Kodambakkam. In 1950, P.S. Ramakrishna Rao and Bhanumathi Ramakrishna, the only female studio owner in Chennai, set up Bharani Studios next to AVM Studios. Other studios in the area included Narasu Studios, owned by Narasu’s Coffee; Rohini Studios, now a warehouse for Food Corporation of India; and B.S. Ranga’s Vikram Studios. Producer K.S. Gopalakrishnan built Karpagam Studios from the profit he made from his film Karpagam. Different film scholars have quoted different numbers of studios in Chennai, ranging from 30 to 100. This incongruity is possibly due to the absence of a standardised definition of what constitutes a studio.

Parasakthi was an important film released under the AVM banner in 1952. The film, like most other films of the time, was also originally a play written by M.S. Balasundaram of Dravidar Kazhagam. Meiyappan, along with Dravidian movement activist Perumal, watched it and hired M. Karunanidhi, who later became chief minister of Tamil Nadu, to write the screenplay. Incidentally, both Karunanidhi and his political mentor Annadurai were working as screenplay writers with AVM Studios in the early 1950s. M.S.S. Pandian’s essay on Parasakthi talks about its anti-Brahmanical, anti-Congress, anti-Hindi imperialism and pro-Tamil nationalistic narrative.[4] This rebellious DMK film was released to the cultural elite, who were largely Congress party sympathisers and, unlike during the beginnings of cinema in Madras, also by now cinema patrons. Parasakthi, like Naam Iruvar, opened with a song, but in this instance, it was the Dravidian activist-poet Bharatidasan’s songs about sociopolitical issues in Madras State. Swarnavel E. Pillai in his book explores Parasakthi, shot almost entirely at the new studio in Kodambakkam, from the perspective of the economy of space. He writes,

AVM Studios complex, which had made its complete transition from Karaikkudi; the thatched cottages and the materials inside were transported from Karaikkudi by truck, and the cottages were transformed into concrete buildings in Madras. Therefore, the film innovatively uses various blocks of the studio space as a constructed stage, due to their enclosed and intimate quality, mainly for its protagonist Gunasekaran to deliver his monologues and for Kalyani to share her plight directly with the audience, either through her dialogues or songs.[5]

The arrival of television in the late 50s and early 60s was the first point of departure from the well-established business of studio-born cinema. Prasad Studios set up in 1956 would go on to make important inroads in similar infrastructure building after the death of its founder L.V. Prasad. Prasad Film Labs initially set as a modern additive colour processing and printing lab in the mid 70s, eventually concentrated on making 70 mm release prints, introducing Panavision technology to India, besides providing filmmaking equipment on rent. AVM Studios never transformed their black-and-white cine lab to colour and went on to work mainly with Prasad and Gemini labs for their productions. It was not until the introduction of colour television in the early 80s that studio-born celluloid cinema was truly threatened. Around this time, studios started catering to the television industry by renting out floors and producing TV dramas.

R. Parameswaran, in charge of the AVM's cine lab since the early 50s, recalls how AVM’s success with films remained intact till 1968 and was first interrupted by a trade union strike of workers demanding salaries on a par with the Vijaya-Vauhini Studios. This led to the studio shutting down for 18 months. As it picked up pace again after resolving the strikes, a second strike for an unknown cause began in 1975. By the end of the 1970s, the industrial studio system, which was somewhat feudal in labour relations, was headed towards a steady decline, mirrored by an assured rise in the power of the individual star, director and artists. The recession and financial struggles within the system also contributed towards this.

Technological shifts in the medium brought cinema out of the confines of the studio complex. The American Mitchell camera (Fig. 4) made in 1919 was designed for silent films and therefore was not a quiet camera with noise control. This noisy camera went through a series of technological developments over the years as electric motors kept being added, making the device more sophisticated.

With the coming of the talkies, the camera had to be made quieter. To ensure soundproofing, the camera of the early talkie decades ended up being heavy and cumbersome, and it was not travel-friendly. For the sake of better sound, noisy arc lights had to be abandoned as well.

The advent of playback and dubbing technology introduced in the Tamil cinema industry by AVM Studios was the first dent in the dependency of films on the studio system. With work gradually shifting to sound recording studios, the importance of sound recording on the sound-controlled floor started dwindling. Besides, when film stock with improved film speed was introduced, the necessity of shooting with bright studio lights diminished. Both these components made it possible to shoot scenes at lower light levels and diminished the importance of light control within studio confines. With reduced stress on sound control in studio spaces, the heavy-blimped cameras were replaced with a noiseless, lightweight, highly portable Arriflex 35BL in 1972. The advent of this camera in Chennai inspired directors. It made it possible for them to move out of restricted spaces and controlled settings, and take on-location or outdoor shoots.

Last leg of the Studio’s Journey: Arrival of video technology, digital cameras, and the Internet

In 1979, Meiyappan passed away. His 25-acre cinema business passed on to his four sons—Saravanan, Murugan, Kumaran and Balasubramanian. While Murugan was entrusted with AVM's cine lab, Saravanan and Balasubramanian took on AVM Productions.

By this time, Saravanan had already been the executive producer of AVM Productions for two decades. The reign of the studio floors kept weakening while technology ushered in newer changes with the introduction of telecine in the late 80s. This was the beginning of a new era of video technology that would quickly morph into digital practices. Telecine made it possible to transfer film stock into video format meant to be screened on television or circulated as video tapes, including VHS and Betacam. Post-production work started constantly evolving towards digital cinema. Around this time, the distinguished Steenbeck flatbed editing and Moviola linear editing machines (Figs 5 and 6) were replaced by digital nonlinear editing. Digital scanners were routinely employed to improve visuals and introduce effects.

In the early 2000s, Red introduced their first digital camera followed by Arri in 2007 introducing the digital camera Arri D-20. In 2011, the popularity of the digital cameras made Arri and Panavision declare that they were discontinuing the production of analogue cameras. By the first decade of the 2000s, the curtain truly fell on all the remaining celluloid aspects of cinema. The economic liberalisation of the 90s and the introduction of multiplex cinemas in the early 2000s influenced the taste of the audience and instigated shifts in the narrative and visual content of Tamil as well as Indian cinema.

The reign of the production house lasted longer than that of the studio floors. Even in 1983, AVM produced a film, Thoongadhey Thambi Thoongadhey, starring Kamal Hassan. It had a 263-day run at the box office. In 2007, AVM Productions released the blockbuster Sivaji: The Boss, starring Rajinikanth. The protagonist Sivaji was a software architect caught in a complex sci-fi high-tech plot. The film was shot in many places including Ramoji Film City, Hyderabad. Although captured on super 35-mm film stock, this film was scanned, digitally graded and transferred to 4K digital cinema projection, introducing the latter to the Tamil film industry. In 2012, this film was re-released in 3D format.

In 2011, AVM’s 175th and last film production Mudhal Idam was released. By this time, AVM Productions had entirely moved to producing television dramas. In 2014, the fourth generation of the AVM family, granddaughters of M. Saravanan (Aruna and Aparna Guhan), released the first direct-to-stream film, Idhuvum Kadandhu Pogum, under AVM Productions on YouTube. Thereby, AVM made another effort to reconcile with its times and ascertain the possibility of rehabilitating itself as a production house despite lost glory.

In 2015, as a documentary was being made on the extraordinary life of AVM Studios, marking its 70th year, part of the studio was also demolished to make way for a high-rise apartment complex. According to media coverage, the part of the studio belonging to Balasubramanian was broken down as he intended to move to the real-estate business with seven acres of this land. Newspaper articles detailed how, besides the air-conditioned shooting floors and preview theatre, a bus stop set was also being brought down.[6] The film narrative desired the city’s landscapes long before equipment could move out to location shoots. The demolition of the bus stop is a subliminal reference to how access to the real city has appropriated the requirement for the constructed city within the studio confines.

The rest of AVM Studios space shows up on the Internet as available to the public. Online city guides such as Little Black Book Chennai list AVM Garden Villa as vintage properties available to rent for family events (Fig. 7). Popularly known as Chettiar Bungalow, this was the residence of Meiyappan. Built by the famous architect P.S. Govinda Rao in 1965, hundreds of films have been shot here. This peculiar landscape—with fountains, spiralling staircases, vintage statues and chandeliers that graced the silver screen—is available to help bring a glorious cinematic grandeur closer to the lives of the consumers. The Mylapore house of A.V. Meiyappan and his wife Rajeshwari, fondly called the Devakottai house by the family, functions as a lavish wedding venue now. The AVM School and housing complex initially set up by A.V. Meiyappan to cater to his employees are still functioning under the guidance of Saravanan and his son, Guhan.

In the neighbourhood of Kodambakkam today, Bharani and AVM stand tall as residential high-rises, Vijaya-Vauhini has been broken into Forum Vijaya Shopping Mall and Vijaya Hospital, and Rohini Studios manages to retain its past structural aura, even if not its glory, with its studio architecture intact as a warehouse of Food Corporation of India.

The cinema industry is continuously morphing, and different genres of filmmaking function with different parameters today. A vast and diverse filmic knowledge and apparatus retraced into the past as skillsets and professions died and were recast, machines were junked or put in glass cases, and workers were asked to leave or learn contemporary practices. Cinema survived all and continues to exist as the most popular form of entertainment and art as audiences break into songs and dance with the protagonists, and interact with this living medium inside the comforting dark cave of a cinema theatre.

Film history is an established discipline across the world today. But the narratives of studios and laboratories, cinematic mediums and formats, obsolete technologies and machineries are often reconstructed in the realm of oral culture. The accounts of technician-artists like film colourists, printers, processors, studio carpenters, boom holders and costume designers who fell into obsolescence remain largely ambiguous. If we are to comprehend and savour the medium better, the changes in cinematic technologies, which spanned a few years, require to be investigated as an inseparable part of film history. The science-fiction world of the past, replete with machines lost and found, dripping chemicals in damp rooms, and unruly consumers who hoard obsolete apparatuses in their attic makes the chronicle of the moving image far-reaching.

[1] Baalyu, AVM Speaks (Enathu Vazhkai Anubavangal).

[3] Baalyu, AVM Speaks (Enathu Vazhkai Anubavangal).

[4] Pandian, ‘Parasakthi: Life and Times of a DMK Film’.

[5] Pillai, Madras Studios— Narrative, Genre, and Ideology in Tamil Cinema.

[6] Manikandan, ‘From Reel to Real: The Story of AVM Studios’.

Bibliography

Baalyu. AVM Speaks (Enathu Vazhkai Anubavangal). Chennai: Vadapalani Press, 1974.

Manikandan, K. 'From Reel to Real: The Story of AVM Studios.' The Hindu, Chennai, June 11, 2015. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai/from-reel-to-real-the-story-of-avm-studios/article7302946.ece (Last accessed on July 2, 2019).

Pillai, Swarnavel Eswaran. Madras Studios—Narrative, Genre, and Ideology in Tamil Cinema. New Delhi: SAGE Publishers, 2015.

Pandian, M.S.S. ‘Parasakthi: Life and Times of a DMK Film.’ Economic and Political Weekly 26, no. 11/12 (1991): 751–770.