Denied a life of dignity, for hundreds of years widows from across India have ended up in the holy city of Vrindavan in search of inner peace and to live an honourable life. For the almost 21,000 destitute widows, Vrindavan initially had only six shelter homes—Meera Sahbhagini Ashram, three small homestays administered by the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), and two more in Chaitanya Vihar, all run by the government. All these were widely criticised for their dismal state, bare-bones facilities and corruption. Funds allocated for the widows would never reach the right hands and many would go hungry, beg on the streets, and even death would not guarantee them dignity.

Such was the poor condition of these shelters, in 2012, the Supreme Court of India requested Sulabh International Social Service Organisation to make a concerted effort towards the betterment of the lives of these widows. Sulabh immediately responded to this enormous challenge, and under the guidance of its founder, Dr Bindeshwar Pathak, began the project of improving the condition of these shelters— providing funds for food, clothing and medical aid to the numerous women living there. Apart from taking care of their basic needs, education and economic empowerment, Dr Pathak realized it was vital to institute social acceptance of these women through their inclusion in festivals and cultural events. Nowhere is Holi celebrated with such fervor as in Vrindavan, the land of Radha and Krishna. Thousands of pilgrims and tourists throng Brajbhoomi during this festival, and the town is drenched in colour. Ironically, for the countless widows who call Vrindavan home, colours are taboo, a form of denial of their existence.

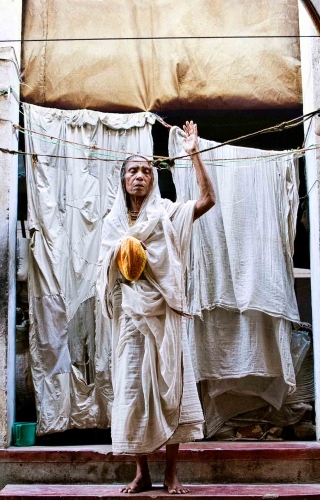

One of the many forms of social discrimination against women in India is the treatment meted out to widows. In our country, even in the 21st century, widowhood is a curse. Upon the death of the husband, societal conventions expect women to desexualize herself overnight. She is forced to give up all worldly pleasures, wear only white garments and have her hair cut off. The thaalis full of vermillion, flame and saffron, and playful exchanges with other people are not for them. The widows remained onlookers, imprisoned behind the bars of their windows, a species of social pariah debarred from every celebration.

Centuries of regressive social barriers came crashing down in 2013 when, for the first time in 250 years, celebrations and vibrant colours made a riotous comeback in their lives. That year, Holi was more than a mere exchange of colours, it was the breaking of taboos, the defiance of tradition. Meera Sahbhagini Ashram was adorned with rangolis made of rose petals and gulal. There was intoxication in the air, as the widows threw flower petals at each other and played phoolonwali holi. Many were dressed up as Radha and Krishna and danced to the tunes of bhajans, celebrating Raas Leela. In a similar fashion, many other ashrams and homes witnessed a joyful transformation that day. In Vrindavan, the die of change had finally been cast.

Personal account

In the year 2013, I happened to visit Vrindavan, a city in Uttar Pradesh which is associated with the life of Krishna. A chance visit to a shelter home opened my eyes to the world of a widow. What I saw affected me deeply and will probably remain with me for the rest of my life.

I saw a dark room with more than a dozen beds lined up against two walls. There on the beds sat women in tattered white saris with a blank look in their eyes. Most of them were widows, in their 70s or older. Who were these women? Where did they come from? Why weren’t their families there with them? Many such questions crowded my head. I tried talking to them, some of them poured their hearts out, some didn’t remember, or did not wish to remember. But the one-on-one conversations with them that day impelled me to go back to Vrindavan again and again.

Over the course of four years, I made countless visits to Vrindavan, to talk to as many widows as I could, and gain as much insight into their lives as possible. I have lost count of the number of pictures I have taken in the many shelter homes across Vrindavan. Then one day a woman asked me sharply, ‘Why do you keep asking us for our stories? What good will this bring? Will it really help us?’ This episode made me question my own faith and motivation behind the countless shoots. I realized that there was a huge need to create more awareness on the subject, as the phenomenon of abandoning widows isn’t really a thing of the past. Even today, hundreds of widows are forced to leave home, and end up in shelter homes, or worse, on the streets of Vrindavan. This practice is not restricted to the less privileged but also prevails in educated and well-to-do families.

I wanted to take the story of these women to every home, in the hope of bringing about a change in the mindset of people, and of exposing the hypocrisy in our society that claims to have progressed beyond discrimination between men and women.

In this endeavour, I was fortunate enough to have had one-on-one conversations with Dr Bindeshwar Pathak, the founder of Sulabh International, and Dr Mohini Giri, founder of Ma Dham in Vrindavan, both credited with groundbreaking work in this field. I attended many festivals, such as Holi, Diwali, and even travelled to Kolkata with many of these widows to attend the Durga Puja celebrations. I was witness to the slow but steady change that was taking place in their lives. It was an uplifting and empowering experience for me as a photographer as well as a documenter of historical changes.