Chittaranjan Borah is an artist, folk art collector and writer on various subjects pertaining to local history and folk arts. He is the founder of an organisation called Kolong Kala Kendra in Puranigudam, Assam, that works towards preservation and promotion of different forms of traditional arts and crafts of Assam. The centre also has a museum that houses old artefacts, mostly from Assam. As an artist, along with manuscript painting, Chittaranjan Borah also practices traditional form of mask making, terracotta and wood carving.

Chittaranjan Borah is one of the few artists to revive and carry forward the tradition of manuscript painting when it was on the verge of decline. In this interview, he talks about his personal growth as an artist, steps that were taken by him and his organisation to promote manuscript painting together with narrating and explaining the history, context and essence of the art form and of the artists who practise it.

Meghna Baruah: What were the family and childhood influences that led you to be more inclined towards art?

Chittaranjan Borah: As far as I know, my father's family was associated with the royal court and administration in Assam and our ancestral roots lie in Majuli. It is an interesting fact that most of the people in Nagaon had migrated from upper/eastern Assam. We had migrated from upper Assam too but we came much later, much after Momai Tamuli Borbora built Nagaon. We first reached a place called Nonoi and finally settled in Puronigudam. I have not found mention of any member in our family being associated with art. However, when I see old artefacts like our ancestral palanquin, I presume that some of our relatives must have appreciated arts. That is why we find such old artifacts even now.

Apart from my father’s ancestors, my mother’s side of the family is also a very cultured one. My grandfather Dharanidhar Mazindar had written an abridged history of Puronigudam. I consider him as the person who instilled in me, at a young age, the interest for culture, society and arts. I had spent around four years with him when my father was transfered to Cachar for work. I stayed with my grandfather so that I could continue my studies. I consider these years to be really valuable. When I stayed with my grandfather at Murhani, an art school named Anirban Chitrangon Bidyalaya was established in Puronigudam in 1983. The political situation in Assam at that point of time was quite disturbing. I had taken admission and studied art in that school from 1983 to 1992.

My guru was artist Pranab Baruah. Pranab Baruah sir taught and made us aware about art, society and life at large in various ways. He instilled the idea in me that an artist is not only involved with creation of paintings or sculptures but that art has an essence in life as a whole. These ideas made us eager to learn about subjects that had an aesthetic value. It is also through my teacher that my interest for manuscript painting began. He used to tell us that manuscript painting was a rich and vibrant tradition in Assam for around three hundred years but it gradually declined. He also said that he had never met a single artist in any satra (Vaishnavite monastery) who practised this art form. This was a shocking revelation for me. How and why could an art form that existed for so many centuries be in such a state of decline?

When I completed my studies I started to focus and devote my time to learn not only about manuscript painting but also about different kinds of folk arts and crafts that were practised in Assam. This study also included those art forms that were on the verge of decline. I wanted to find out the status of such traditions and for that purpose I travelled to different parts of Assam. During my travels, I observed that traditions like terracotta and mask making were still continuing to some extent, especially in parts of upper Assam. However, at that point of time, I did not come across anyone involved in manuscript painting. I also went to Auniati Satra but, unfortunately, I could not find an artist still practicing manuscript painting there.

Luckily, in 2001 our organisation Kolong Kala Kendra had conducted an exhibition on the theme ‘Ganesha’ at Srimanta Sankaradeva Kalakshetra, Guwahati. Auniati Satra had organised a demonstration on their various forms of art, craft and dance at the institution as well. There I was fortunate to meet a person named Budhindra Nath Borpathak during that demonstration. Sri Pathak was chief pathak (Borpathak) at Auniati Satra, meaning one who has the responsibility of reading traditional scriptures. I saw him creating a lata-kata-puthi during the demonstration, meaning drawing and painting a floral border around the text of a traditional sanchi manuscript. I was elated to meet him because I had been working very hard to find someone like him. I started asking him details about the process of painting and writing. However, on enquiring, he would only say a word or two but did not want to reveal too many details.

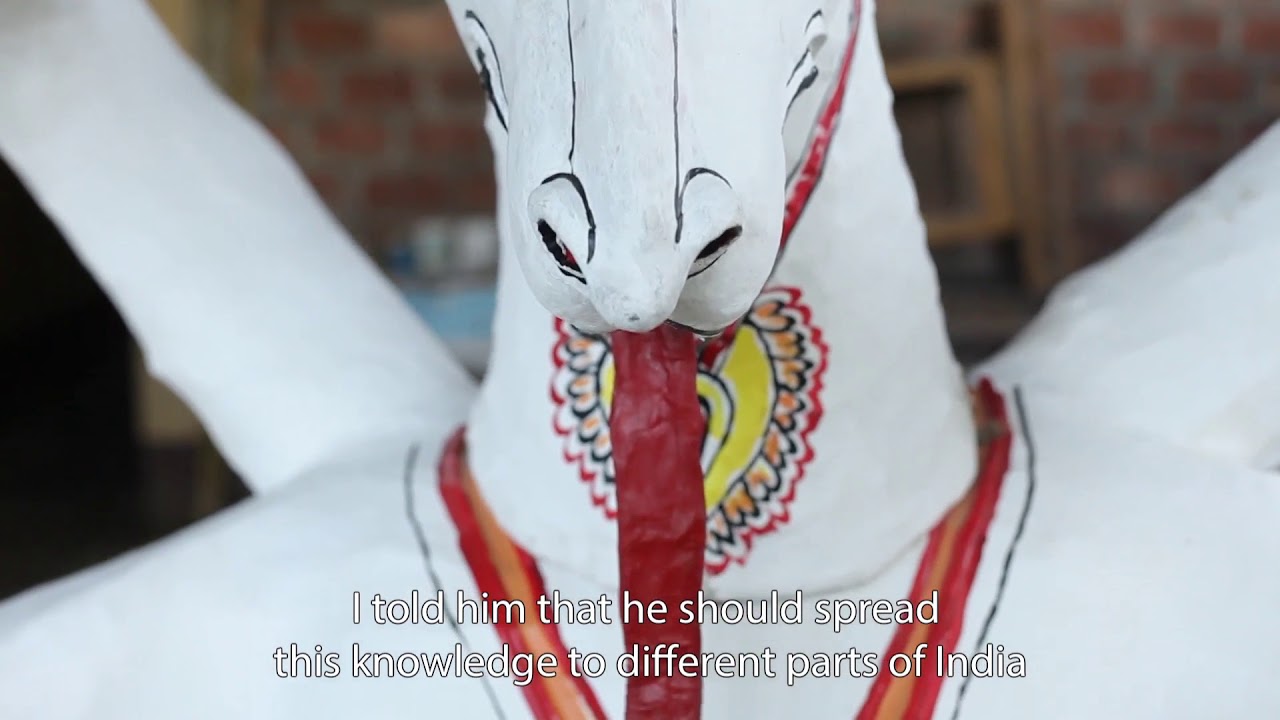

Later I told him that I was a journalist and requested him to share knowledge of this traditional painting form with me. It is true that at one point of time I was working as a journalist but I had left that profession long ago. I had to lie to him, as he was not saying anything. I told him that he should spread this knowledge to different parts of India and he may also have to visit various places in this regard. He started speaking gradually after a lot of pestering. Once he opened up, he also mentioned to me that traditional knowledge of this kind should not be shared with anyone and everyone. Many art and dance forms have moved outside the institution of satras (Vaishnavite monasteries) and it has somehow lost its own character by mixing up with other forms. I could understand what he was trying to say. My intention was to sincerely learn the art form from him. I consider him my guru to this day and I have deep respect for him. I learnt the art of manuscript painting from Budhindra Nath Borpathak in 2001. Post-2001 I kept practicing on my own and had to go through a lot of ups and downs during this process. One should use glue with colours while painting on manuscripts and it is very difficult to get the right proportion. That comes with a lot of practice.

The institution of satras is culturally very rich. Satras have their own form of dance, music, woodwork and mask work. They also make hand fans and costumes that are used during bhaonas (traditional form of drama). It is like a huge cultural enterprise. Most of the Vaishnavite monks in satras are keulia bhakats, i.e. they maintain celibacy throughout their lives. They have ample time with themselves and they devote their time in different creative pursuits after carrying out their domestic chores like cooking and cleaning. My guru had learnt manuscript painting from one such bhakat. He spent a number of years learning painting, woodwork and making of manuscript from his senior. Budhindra Nath Borpathak also used to make and play musical instruments. He had a lot of qualities and he learnt all of it in satras. Study of different arts and crafts has been continuing in satras for many centuries.

It is interesting to know that Budhindra Nath Pathak was the only person who had kept the tradition of manuscript painting alive, primarily by making lata-kata-puthis. I also came to know that he was the last person to continue this art form by using traditional colours like hengul, haital and khorimati. Apart from him there were some artists in upper Assam who knew the process of traditional manuscript creation and writing but they were not involved with painting.

MB: How did you and your organisation promote manuscript painting among others? What are the struggles that you had to endure during this process?

CB: After learning from my guru and practicing for a number of years I taught manuscript painting to two more people: one boy and a girl who used to visit my centre to study the painting form. In 2004, I exhibited the work that we had done on the foundation day of our centre. I think, along with a number of students, Mridu Moucham Bora and scholar Dr Naren Kalita were present on that day. I mentioned during the exhibition that manuscript painting is a very valuable aspect of Assamese culture and none other than Budhindra Nath Borpathak had kept this tradition alive. I had come across many news reports that had declared that manuscript painting had already disappeared. Such statements were also in a sense true since Sri Borpathak used to make only lata-kata-puthis and not paintings. Even then some part of it still existed because of him. Sri Pathak did not pass on this knowledge to anyone at the satra. On enquiring I was told that most probably he felt that his importance would have diminished if he passed on the knowledge to others. He is my guru and I find it difficult to talk about him negatively. I am not sure what were the exact reasons for his inhibitions and what was going on in his mind. I know that he was partly apprehensive because he did not want art forms from satras to lose their character and purity.

When he later heard that I trained a few people in manuscript painting at my centre, he asked me to carefully choose only those students who could carry forward the tradition of painting with genuine interest. He also mentioned to me a number of times that one should remain humble and bereft of ego even after they learn and gain knowledge on something. According to him students do not even remember their gurus once their training is over. He was vehemently against this kind of an attitude. I think that is why he was apprehensive to teach people and did not reveal anything initially.

I could understand his reasons for holding back knowledge of this art form. At the same time I felt that if a tradition did not pass on from one generation to another then it would surely die. Therefore, in order to train new people in this art form we conducted a workshop on manuscript painting on January 1, 2006 (we could not conduct it in 2005 as we had organised bhaona that year). In that workshop Mridu Moucham Bora and other trainees, mostly from Dhing and Nagaon, had joined. It was a grand workshop. Initially it went on for five days and later it was extended to eight days. A number of trainees have learned manuscript painting through our workshop and people like Mridu Moucham Bora are imparting training to some students at present.

Over a period of time, I felt that my guru’s inhibitions were there for a genuine reason. I feel that at present some artists concentrate more on spreading the work and publicising the art form rather than focusing on learning it thoroughly. While practicing manuscript painting, I feel it is very important that the artist works in a silent and patient manner. Earlier artists used to work with a lot of dedication. I was once told of an artist who had dug a ditch and worked inside it so that he could be away from his family and be completely focused in his work. This is a kind of meditation.

I am not saying that one should not publicise this art form. It should not remain closed within the folds of the manuscript and its box. I am a person with modern ideas. However, every art form has its own intrinsic character and this should be kept intact while carrying it forward. There is presently a lot of media hype about manuscript painting and I like to completely stay away from it. Many people ask me whether I am working in this area or not as they do not see me in media. I want to stick to my beliefs and what my guru has taught me. I think artists working in this area of painting should follow such an approach. Only then can its true character be rescued.

We had found an old manuscript at a place called Pathori and we have preserved it at our centre (Kolong Kala Kendra). The manuscript is around 200-250 years old and there is a painting in one of its folios. Some of the people who are associated with our centre were really happy and impressed to see this beautiful work. They felt that one should work hard to keep the tradition of manuscript painting alive. They asked me to practice as much as possible.

When I was in school I had planted sanchi trees in my backyard from where sanchi bark can be peeled out. The seed of this idea was instilled in me since my school days. I had planted around fifty trees then and now around twenty-five of them have survived. The name of the manuscript, which we have preserved at our centre is Moni Chandra Ghuxo Parba. According to the donor of the manuscript, it is around five hundred years old but Dr.Naren Kalita has assumed it to be around two hundred to two hundred and fifty years old. A different kind of enthusiasm had risen in us when we found this manuscript. In order to spread the tradition among more people we started to informally train a few enthusiastic trainees. Many students also came to us to write papers on this topic. Since we were already working in this area and students were new to it, most of the information had to be provided by us. These enquiries compelled us to keep ourselves updated and read more about manuscript painting. Some students were so talented that they would come up with unique questions and we had to be prepared to give appropriate answers to them. If there had been any discovery of manuscript/s, we would immediately gather information about it.

I would like to mention here that my second guru in the area of manuscript painting is Dr Naren Kalita. I have learned the practical aspects of the art form from Sri Budhindra Nath Borpathak, and theoretically I have learned a lot from Dr Naren Kalita. I have been greatly inspired by his book Asamar Puthichitra (Manuscript Paintings of Assam), which was published by Publication Board Assam. As a student I always pestered and troubled Dr Kalita for information and knowledge and to this day I seek guidance from him. I learnt a lot about making of colours and processing of tulapat (paper made of cotton) from Dr Naren Kalita. After following his instructions I tried making tulapat a number of times and was successful the fourth time. I have even made and sold paintings of it. I have always had a lot of regard and respect Dr Kalita.

I have had to go through a lot of struggle to learn manuscript painting. I had to visit different satras where I could not find any information most of the times; I had to meet people who hailed from the world of art and academics like Birendra Nath Datta and Nilamani Phukan. I only could not visit one satra at that point of time and that is Bor Elengi Bogiai Satra. Artist Jadab Mahanta is associated with this satra. Most probably colour work of hengul and haital was practised till recently at Bor Elengi Bogiai Satra especially on woodwork and while making of guru asanas. However, I do not know if the artists there created manuscript paintings.

Some scholars like Dr Naren Kalita say that manuscript painting especially figurative study was revived in a new way first at our centre. I don’t know, if I am at fault when even I say this. There has been a lot of struggle in trying to keep this tradition alive. When I used to make tulapat, cotton had to be kept in water so that it decays. This used to give rise to a lot of stench in and around the house. My family and home could not completely live in a clean atmosphere that a home should usually enjoy. In a way this was also a struggle.

MB: Influence of dance in manuscript painting?

CB: Many elements of dance have been incorporated in our paintings. There is a position called tribhanga in dance and a similar position is also visible in the figures of our paintings. Additionally some hand mudras or gestures are also used in manuscript paintings, which are similar to dance. The manuscript Chitra Bhagawat which was discovered at Bali Satra, consists of many figures in which one can witness gracefulness of dance. Some of our experts have also observed that Sattriya School of manuscript painting consists of certain thuls, meaning a certain style of painting, which is practised by one artist, and followed by a group of other artists. For example, suppose the neck and arms of figures are longer in one thul they may look different in the work and style of another artist and his co-artists.

Such a pattern is also visible in our Borgeets (a special series of songs written by Srimanta Sankardeva & Srimanta Madhabdeva); there are different styles of Borgeet in Upper Assam, Majuli, Nagaon and Borpeta. In some of these thuls of manuscript painting, one can witness that their figurative work has a lot of influence from dance. For example, when Krishna is walking with his friends, it looks like as if they are dancing while walking. However, it will take us a long time to find out minute details of such influences.

MB: What kind of themes do you cover and do you follow a particular school of manuscript painting?

CB: Initially, while learning the art form we mostly used to copy from old manuscripts. Post the stage of reproduction of paintings, we felt that one should not only copy but also create new work. I discussed this issue with many experts like Dr Naren Kalita, Moushumi Kandali and Nilamani Phukan . They suggested that one has to create work on new topics and themes by keeping the old style intact. If the current period is not reflected in paintings that are created today, then it is doubtful whether the next generations will hold such paintings in high value. These discussions influenced me to a large extent. I started making paintings that addressed some current themes. For example, I made this painting on the theme ‘Women’. The style that I have followed is similar to what can be found in old manuscripts. But I have introduced elements like a woman wearing churidar and kurta along with other women wearing our traditional attire mekhela sador because that is what we see women and girls wearing now.

Moreover, I have also used some text along with the painting because most of our earlier manuscripts had text with paintings. I have composed and written a stanza for the painting that reads - 'Nari bhoilo boxumoti jagate janoi, prithi viroh bharo xohi ase xorbomoi, tothapi othiro taro jibono niloi, ehi kotha nogonile ghotibo proloi.' Through this painting I have tried to convey the hardships that women go through: they have to keep their spouses happy, bear children and take care of them. Even then they are mostly ill-treated by society. I have compared women with prakriti (nature) and represented the earth inside a woman’s womb. Dr Naren Kalita really likes this painting. Similarly, I have created another painting on the theme ‘We are on the same boat brother’. The painting represents all kinds of people sitting on one boat. The third painting is on one of the cultural icons of Assam: Jyoti Prasad Agarwala. Style of painting in these works is traditional but the themes are modern. I have attempted to bring about continuity to this tradition through my work. Some people have however, also criticised me for doing such work. I have not given too much heed to the critics and have gone ahead with my work.

It is interesting to know that the horizontal character of manuscript paintings of Assam is quite rare and not found in painting forms of other parts of India apart from some wall paintings. Use of arches, red background and figures being drawn in one line are some other important features. Most of the figures are also drawn in side profile.

I plan to continue drawing and painting in the style of Sattriya School. Some people also like to call it Vaishnav School. However, I feel Sattriya School is more appropriate since this style existed and developed for many centuries within the institution of satras. When the bark is removed from the sanchi tree it is usually cut in a vertical manner and not cut around the trunk of the tree. The tree might die if the bark is cut horizontally. This feature also determines the character of our manuscript paintings. In Assam, we can still find a good number of sanchi trees.

MB: What do you think about the kind of work that is being produced now by most of the artists?

CB: Most of the work done now by artists is copied from earlier work. Even while attempting to do so, I feel they have not been able to follow it properly. There seems to be some misrepresentation of figures and in appearance of face. Their work lacks finesse and is not like it earlier used to be. Another character of old paintings is that most of them were opaque in nature. The same smoothness and opaqueness cannot be seen in paintings now. Most of the artists do not have the patience to mix and apply the same tone of colour throughout a painting. Work done by some of artists in the old manuscripts was really beautiful.

We have not had the opportunity to have a look at most of the original manuscript paintings. Dr Naren Kalita has shown us pictures of many paintings. I could see some actual paintings at Kamrup Anusandhan Samiti and I have also been lucky to see the original paintings of Chitra Bhagawat at Bali Satra. These beautiful and ancient paintings have really inspired me. I have heard that even now there are some manuscripts that are yet to be open to public view.

MB: Has there been any connection between Sattriya manuscripts and Buddhist manuscripts and culture?

CB: Sattriya manuscripts have close connection with Buddhist manuscripts and manuscripts of Tai language. Phung Chin is a Tai manuscript, which was created in AD 1437 on tulapat. The format of the manuscript is not horizontal but vertical. It depicts Buddha and consists of information on tantra, magic and mandalas. One can see similar depictions in some Sattriya manuscripts like Ananda-Lahari and Tantra Sar. When we talk about manuscript painting we straightaway talk only about Sattriya paintings. However, I think Tai manuscripts were an important chapter in the development of manuscript paintings in this region. National Museum had brought out some prints of manuscript paintings of Assam and that collection consisted of a few Buddhist and Tai manuscript too.

MB: Can you tell us more about the history of manuscript painting?

CB: Manuscript painting has a long history. The inclusion of some blank sanchi manuscripts, brushes and colours in a gift from King Bhaskarbarman of then Assam to King Harsavardhana of Kanouj (North India) indicates that the tradition of manuscript writing on sanchipat was there in Assam in the 7th century or before. There was a gap for many centuries after 7th century and there is no proof of existence of any art form post this period. Gradually we found manuscripts like Phung Chin that were written in Tai language. Later Xostho Skandha Bhagawat (Bhagavata-Purana, VI), which was found in Puran Burka Satra, can be considered to be the earliest illustrated manuscript within Sattriya School. Chitra Bhagawat from Bali Satra was also made around the same time, which was followed by Anadi Patan of Kuji Satra created in eighteenth century. Sankaradeva composed the text of Anadi Patan many centuries earlier but the illustrated manuscript was painted later. There were more than ninety illustrated manuscripts that were discovered at a later stage in Assam.

Now the question remains as to where has this school been inspired from? Manuscript paintings of Assam have an influence of Lodi paintings that existed before 1556 and prior to advent of Mughals. One can also see influence of Kangra and Jain paintings in our manuscripts. When King Rudra Singha brought Dilbar and Dosai for drawing of illustrations of Hastividyarnava, these two artists infused Mughal miniature art in our manuscripts. Later one could also see British guns and weapons in some of our paintings. There might have been a British influence too. Although Lodi, Jain, Kangra and Mughal paintings have influenced our artists, yet they have not adopted one painting form completely. They have been inspired from different art forms and given birth to a new style.

We have not found any proof that Sankaradeva himself drew on manuscripts. However, we can assume from Charitra Puthis that Sankaradeva used to draw. We do not know if he drew on manuscripts but may have created backdrops for stage performances. At that point of time, backdrops were used during dramas. It is mentioned that when Sankaradeva performed his first drama Chinnayatra at Bordowa, he had drawn and used stage backdrop and masks for the first time. This is how the tradition gradually emerged.

MB: What according to you are reasons for decline of manuscript painting?

CB: Manuscript painting of Assam was a living tradition during seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth century. Manuscript painting and writing still survived after the British had entered Assam and after the advent of Moamoria rebellion and Burmese invasion. However, when British introduced paper and the technology of printing press, institutions and firms also began printing of religious texts. Auniati Satra brought out printed religious books and they were also published from a press in Nagaon. Making of traditional manuscript was very time consuming, expensive and required a lot of hard work. Demand for artists who were creating traditional manuscripts gradually declined. This situation changed further after Independence. People did not demand for traditional things anymore and artists almost stopped working on manuscripts. Demand for sanchi bark had greatly vanished after introduction of paper. Few artists continued only to keep the tradition alive. Later even colour illustrations could be printed along with text, which resulted in complete decline of this art form. Artists were no more paid for the hard work they did.

MB: How can manuscript painting be developed to cater to the current needs?

CB: There is a need to work towards development of manuscript painting and if it does not adapt to the present situation it may not survive. For example, I have made a welcome note on sanchi bark using traditional ink and haital. These kind of innovations have to be made to cater to the present needs. I am in touch with National Mission for Manuscripts. We have around two hundred manuscripts at our centre. There is a huge need for preservation of old manuscripts. It is through these works of art that we can access knowledge about the past. I consider this task very important and that is why I am involved in the process of preservation of old manuscripts.