Introduction

Visual arts in India have existed evolved over many centuries and are characterized by diverse styles. In Assam, the art of painting developed around the culture of manuscript illustration in line and colour (Kalita 2009). There is historical reference to the art of painting in Assam in the Harsha Charita, with mention of gifts in the form of panels for painting on Agaru bark (Aquilaria Agalocha) along with brushes and colour pots (Boruah 2010), from the Assamese king Bhaskaravarman (seventh century CE) to Emperor Harsha. On the other hand, the earliest extant (emphasis mine) example of manuscript illustration in Assam is from the Phung Chin manuscript, dated 1473 CE and Suktanta Kyempong in Ahom language and script. These illustrations have been drawn in the Burmese style and have their origin in South East Asia and not in Assam (Choudhury n.d.).

In order to understand the development and current status of manuscript painting in Assam, the article is divided into two sections. The first section outlines the historical development of manuscript painting in Assam. It provides information about different styles of painting, artists involved, materials utilized, various influences and decline of this form of painting. The second section throws light on the current status of manuscript painting in Assam. It provides insights into the development and changes that are taking places among a few existing artists of manuscript painting in Assam.

Section 1

Historical development of manuscript painting in Assam

According to Choudhury (n.d), the art of painting flourished in Assam from the 16th century onwards. The bhakti movement, which spread in the medieval period through the work of Sankaradeva (1449-1569) helped to give birth to a vigorous culture of literature and art. According to Boruah (2010), in the Katha-Guru-Charita, the prose biographies of the Vaishnava saints of Assam, it is stated that Shankaradeva painted sat-vaikuntha (seven celestial worlds) on pressed cotton paper for the theatrical performance, the Chinha-Yatra. Sankaradeva was also responsible for creation of many literary works and his followers later pursued this tradition. Many scholars illustrate that one significant aspect of the movement is that it recognized the worship of sacred scriptures instead of any formal idol made of stone, wood or any other substance. The movement initiated by Sankaradeva laid stress on moral and spiritual development of its a. In this pursuit, the movement introduced among people development of different branches of art such as painting, drama, songs, dance and playing of musical instruments. The religious movement also resulted in the foundation and proliferation of institutions or Vaishnava monasteries known as satras. Establishment of satras was a great boost for the promotion and continuation of literary activities and art in society (Kalita 2009).

Future developments saw proliferation of copying and illustration of manuscripts in countless numbers. One of the earliest dated manuscript that comes from Satra, is a copy of the Bhagavata-purana, Book 6. It is a transcript of the book written by Sankaradeva and was prepared in 1678 for illustration work (Kalita 2009).

Artists involved in manuscript painting

The craftsmen responsible for creation of paintings and penmanship were known as khanikars. Satras patronized and supported them. These craftsmen were traditional carvers primarily associated with woodcrafts and also worked as make-up men during bhaonas or one of the traditional forms of drama in Assam. Their familiarity with colour and form of traditional theatre inspired them to create parallel pictorial forms in the folios of manuscripts. That is why many figural forms appear to dance in pictorial space (Kalita 2009). Although khanikars were responsible for creation of beautiful paintings on manuscripts, there is very little information about them. The artists of the satras mostly believed it to be sacrilegious to inscribe their names in a literary work written by their guru. Khanikars were clerics of the satras and their primary duty was to render religious services regularly. They cultivated different art activities to supplement their normal clerical functions. Their devotion to the movement led them to render many paintings in a single manuscript.

Different schools of manuscript painting of Assam

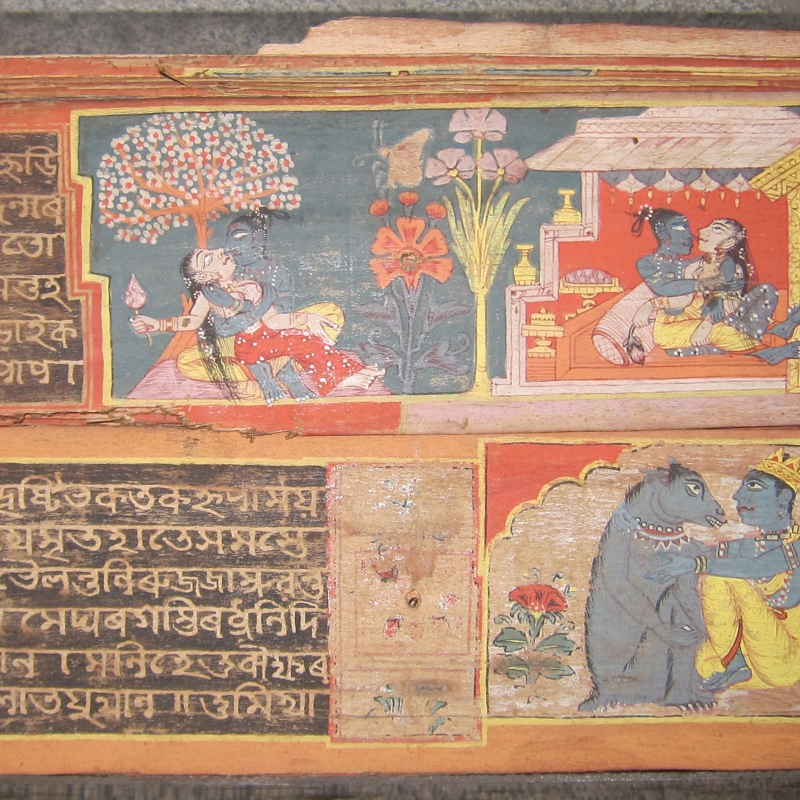

The pictorial style that developed within the ambit of satras and that was inaugurated by the khanikars may be designated as Satriya. The earliest example of illustrated manuscripts of Assam has come from Satriya style of painting (Kalita 2009).

During the prime period of Ahom rule in Assam in the 18th century, there developed another painting style, which was influenced by the Mughal principles of pictorial art. The new style of painting was named as the Court style or Royal style after its association with the Ahom Court of Assam (Kalita 2009). The Ahoms seem to have followed the royal patrons of art as in other parts of India (Neog 1981). These artists appear to have emigrated from the Mughal court to Assam when Mughal dominion over north India was starting to disintegrate.

During the concluding decades of the 18th century the Satriya pictorial idiom moved to Darrang (north bank of the Brahmaputra in Assam). Paintings created in Darrang were somewhat different in style characterized primarily by folk treatment of forms. Kalita (2009) observes reference to the Darrang King, Krisnanarayana in some of these paintings, which point to the fact that they may have been created under the patronage of the Darrang court. This group of manuscript paintings has been categorized under the Darrang style.

Another school of painting in Assam seems to be an offshoot of the Buddhist art of Upper Burma; which is seen in the many Buddhist and semi-Buddhist manuscripts composed in languages of Shan origin. This School appears to have made some influence in Assam’s Vaisnava school (Neog 1981). The Phung Chin manuscript and Suktanta Kyempong in Ahom language and script mentioned earlier also fall under this style of painting which has been termed as the Tai-Ahom style.

Themes of manuscripts in Assam

Manuscripts in Assam consisted of illustrations of stories from the Bhagavata, the Puranas, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata that were mostly created to supplement the text that was written along with these paintings (Boruah n.d.). Some manuscripts even depicted about Manasa Devi, the goddess of snakes and these were wrapped in cobra-skins (Bhuyan 1930).

However, manuscripts were not restricted to religious content only. There were manuscripts on chronicles of kings’ known as buranjis. Manuscripts also provided information on family genealogical history or Vamsavali. Some archived lives and teachings of pontiffs in satras. Independent volumes were written dealing with the lives and achievements of prominent religious reformers and saints, both male and female, which were known as charitra puthis. There are even some like the Hasti-vidyarnava and Ghora-Nidana that is a treatise on elephants and a study on horses, respectively (Goswami 1930). One of the earliest scholars and officials to have touched upon the area of miniature paintings of Assam, Hem Chandra Goswami, was informed about a manuscript on botany while he was undertaking his project and book Descriptive Catalogue of Assamese Manuscripts.

Materials used and process of production in manuscript painting

Manuscript leaves in Assam were made of two materials namely sanchipat, the thicker variety made from the bark of sanchi tree or aloes wood or Aquilaria agallocha and Tulapat leaves of which were made by pressing cotton. The preparation entailed a laborious process of curing, seasoning and polishing the raw slices before the folios could be made to retain the ink. Gait provides a detailed account of the process of preparing sanchipat in an appendix to his History of Assam (Bhuyan 1930). In Assam, ink or mahi was generally prepared with silikha (Terminalia citrina) and bulls urine and sometimes from the extracts of amlaka (phylanthus amblica), elandhu (soot) and barks of some of the trees. This ink is known for its quality as even now the writings are still found to be legible and distinct. Colours used in painting are indigo derived from indigo plant, haital (arsenic sulphide), hengul (mercury sulphide), khorimati used for the colour white and ash derived from silikha for use of black.

Characteristics of manuscript paintings of Assam

Certain general features characterize manuscript painting of Assam. The pictorial format in such paintings is usually of horizontal progression instead of rectangular isolation with which the Mughal artists worked. Among Satriya paintings, postures are angular and the faces are in strict profile except in case of a few figures. Emphasis on contour is also a characteristic feature (Kalita 2009). Physiology and physiognomy is not taken into major consideration and the painter mostly does not attempt individualization of characters. Emphasis is given more to symmetry and movements of groups, which are dynamically presented. Perspective and the third dimension is nowhere in evidence. Successive scenes are flatly brought on the same place like those in celluloid ribbons of cinematograph. Motichandra commenting upon the work of such paintings says: ‘Paintings are usually painted in arched or zigzag pannels. The background is usually monochrome red or at times, blue, grey or brown. The landscape is simple, consisting of blue sky, decorative trees; the water is treated in basket pattern. Lyrical draughtmanship, simple composition, dramatic narration, and splendid colours give the Bhagavata illustrations a charm which distinguish them from similar Bhagavata paintings from Udaipur and elsewhere’ (Neog 1981). Unlike brilliant pigments of the Satriya palette, palette of artists of the Ahom court was an extended one and was predominated more by mute and dark tones like mute greens or olive greens. Mauve, pink and grey were few other pigments, which enriched the colour palette.

Influences on manuscript painting of Assam

Many scholars and artists have commented about the influence of other Indian schools of painting on manuscript illustrations of Assam. Neog (1981) uses reference from various scholars and points out the similarity in these illustrations with the illustrated Jain, Newari and Oriya schools of manuscript paintings. Manuscripts with illuminated margins are known as Lata-kata puthi. This trend of drawing border around manuscripts was a Mughal characteristic (Kalita, personal communication).

Decline of manuscript paintings of Assam

Manuscript paintings of Assam were a vibrant form of art since the 16th century. However, gradually this culture of painting started to decline. In 1769 a section of Vaishnava devotees affiliated to Moamaria order in upper Assam revolted against the Ahom monarchy. This led to collapse of Ahom administration and resultant downfall of creative activities leading to emigration of some artists to different satras. Although devastation caused by the rebellion stopped, the situation again turned violent after 1817 with successive acts of aggressions from the Burmese. The Treaty of Yandaboo in 1826 led to control of East India Company over the territory of Assam and this ended the 600 years old Ahom rule in Assam. In the absence of patrons, there was a fall in the number of skilled artisans. Very few artists of satras kept the flame burning till early 20th century in spite of many hurdles that came their way (Kalita 2009).

Printing technology that was introduced in Assam by American Baptist Missionaries around 1836 is considered as another major reason for the decline of manuscript painting in Assam. Even then, manuscript writing on Sanchi leaves and for religious purposes was still preferred over printed religious books (Bhuyan 1930). Hundreds of manuscripts were also lost or damaged due to recurrent menace of flood and hostile weather conditions in Assam. With time and especially post liberalization, decline of recital from manuscripts during rites diminished to a great extent.The simultaneous absence of manuscript-production also resulted in decrease in both demand and supply (Bhuyan 1930).

Section 2

Present status of manuscript painting of Assam

There was decline in the practice of manuscript painting in Assam as is described above. However, at the same time, there was an increased interest among academics about the preservation and study of these manuscripts. During British rule and after independence, these academics worked to preserve and catalogue some of the manuscript paintings of Assam in various institutions. They also tried to document methods of processing paper, traditional ink and colours. Together with academicians, there were very few artists who against odds kept the tradition of manuscript paintings alive.

At present, there are only a handful of artists who are practicing manuscript painting and writing in Assam. These artists adhere mostly to Satriya style of painting although elements from other schools can also be seen in their work. Some of these artists are associated with Satra while some are not. However, almost all of them have not learned the art form from the institution of Satra. They have individually acquired the skill by gaining knowledge from different scholars, books, pontiffs who had knowledge about manuscript painting and through self-experimentation and practice.

Only a few artists were fortunate to meet and learn some part of manuscript painting and its process from one of the last surviving khanikars at Auniati Satra in Majuli, Assam. This person was a cleric and he had learned manuscript painting from his teachers at the Satra. He was continuing the form of painting mostly by making lata-kata-puthis (form of decorative and colourful border drawn around manuscripts) in the traditional method. Apart from the khanikar at Auniati Satra (who has passed away now) at present, there are khanikars who are engaged in other traditional creative activities like woodwork, make-up work during bhaonas, making of musical instruments and traditional hand-fans.

Most of the current artists take up manuscript painting due to its aesthetic and cultural value. They engage in reproduction of old paintings and some of them have also created new paintings based on either mythological stories or modern themes. Apart from creating paintings on their own these artists are also engaged in propagation of this art form. They conduct workshops and deliver classes to students/individuals.

The use of manuscripts is restricted largely to satras. A few families and individuals also have a custom of placing the traditional manuscript in an altar apart from printed religious books. Artists engage in writing and painting on manuscripts in the traditional method to cater to these few customers. In order to expand the base of current consumers and due to limited availability of sanchipat, tulapat and traditional colours, some artists also engage in painting on new bases like canvas and cloth with the use of synthetic colours. They adhere to the traditional colour palettes and forms of figures and elements. A few artists have also started painting welcome notes and letters of appreciation on sanchi bark. These artists have observed that creation of paintings either in the traditional method or with the use of synthetic colours and modern bases has a good demand among people especially those who visit Assam from other parts of India and world.

These few artists are hopeful that through involvement of a larger number of dedicated artists (with required patience and enthusiasm) may help in promotion of manuscript paintings in Assam in the near future. Naren Kalita observes artists should build finesse and intricacy in their work and should also comprehend the text properly before painting. Proper promotion and marketing will help in gradual development of manuscript paintings of Assam.

Conclusion

Manuscript painting in Assam is part of a rich cultural heritage of Assam and India. It grew during the medieval period through the institution of satras. It was influenced by many painting forms and was used to preserve and spread knowledge through the satras and also in the wider society. During the British and post-independence period, manuscript paintings declined. However, a few artists kept the tradition of this painting form alive through their dedicated work. At present too, a few artists working on this art form are trying to practise, preserve and propagate it among the larger society. They have also tried to incorporate the idioms of changing times and are hopeful that dedicated artists will preserve and carry forward the art form for future use and expression.

References and Further Readings

Bhuyan, S. K. 1930 (Second Edition 2009). ‘A Note on Assamese Manuscripts.’ In Descriptive Catalogue of Assamese Manuscripts, by Hemchandra Goswami, XV-XXX. Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Assam.

Boruah, Samiran. September 2010. ‘Abstract Paintings of the Assamese Bhagavata Purana.’ Marg: A Magazine of the Arts, vol. 62, no. 1.

--------. (n.d.). ‘An Introduction to the Contemporary Paintings in Assam.’ Online at http://indianreview.in/essays/on-paintings/an-introduction-to-the-contemporary-paintings-in-assam/ (viewed on August 10, 2011).

Choudhury, Robin Deb. (n.d.). ‘The Assam School of Manuscript Painting.’ National Museum, New Delhi.

Choudhury, Robin Deb, and Choodamani Nandagopal. 1998. Manuscript Paintings of Assam State Museum (A Catalogue). Guwahati: Directorate of Museums, Assam.

Goswami, Hemchandra. 1930 (Second Edition 2009). Descriptive Catalogue of Assamese Manuscripts. Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Assam.

Hazarika, Biman. 2007. ‘Sattriya School of Painting: Its Development under Bardowa Group of Sattras.’ Proceedings of North-East India History Association, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong.

Kalita, Naren. 2009. Introduction to An Alphabetical Index of Illustrated Manuscripts of Assam. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts.

Neog, Maheswar. 1981 (Second Edition 2011). ‘The Heritage of Fine Arts and Sciences in Assam.’ In Tradition and Style, compiled and edited by Pranavsvarup Neog, 1-34. Guwahati: Professor Maheswar Neog Memorial Trust.

------. 1981 (Second Edition 2011). ‘The Art of Painting in Assam.’ In Tradition and Style, compiled and edited by Pranavsvarup Neog, 167-198. Guwahati: Professor Maheswar Neog Memorial Trust.

Talukdar, Susanta. ‘A Treasure Trove from Assam.’ 2005. Online at http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2215/stories/20050729000206500.htm (viewed on August 12, 2011).

Vatsyayan, Kapila, and Maheswar Neog. 1986. Gita-Govinda in the Assam School of Painting. Guwahati: Publication Board Assam.

www.atributetosankaradeva.org (viewed on August 18, 2011).