Manas National Park is situated in the state of Assam which is in the northeast of India. It lies at the foothills of the Himalayas and the region is one of the main biodiversity hotspots of India. Manas was initially a reserved forest but the Forest Policy Act of 1952 held the poor responsible for deforestation and stated that national forests should be used to produce timber for industry and commerce, not for subsistence by local people, on the grounds that where land is owned rather than held in common, it is usually treated with care. The area was therefore made a wildlife sanctuary. It became a UNESCO World Heritage Site (Natural) in 1985 and a national park in 1990. It is considered to be the pride of Assam and is known for its beauty and richness in terms of both flora and fauna.

The Park got its name from the Goddess Manasa, who is worshipped in this region. Several myths and folklore are attached to this goddess among the inhabitants of Manas. Assam is a land of Shakti-Peetha, hence the female deities are most important. Additionally, the Manas River passes through the heart of the national park. The forests of the reserve were traditionally inhabited and their resources were mainly used by the Bodo, Adivasi and Koch Rajbongshis communities. The area was also preserved as the royal hunting ground for two royal families, the Cooch Behar royal family and the Raja of Gauripur.

The Park has a Project Tiger Reserve (core) since 1973, a Biosphere Reserve (national) since 1989 and an Elephant Reserve (core) since 2003 as well as Important Bird Areas (IBA). The Manas Wildlife Sanctuary provides habitat for 22 of India’s most threatened animals listed in Schedule 1 of India’s National Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972. In total, there are nearly 60 mammal species, 42 reptile species, 7 amphibians and 500 species of birds, of which 26 are globally threatened. There are two major biomes present in Manas, namely, the grassland biomes and the forest biomes. The former includes the pygmy hog, Indian rhinoceros, Bengal florican, etc. The latter includes slow loris, wild pig, capped langur, etc. It is also famous for its population of wild water buffaloes along with rare and endangered endemic wildlife such as the Assam roofed turtle, hispid hare, golden langur and pygmy hog. Manas is also home to one-horned rhinos.

A recent survey revealed the presence of grassland species like pygmy hog and hispid hare in Manas National Park,the last remaining wild habitat of the two species. A total of 17 camp sites under prime grassland habitat were surveyed under two ranges of the park: Bansbari and Bhuyanpara. The specific targets of the survey were the pygmy hog (Porcula salvania) and hispid hare (Caprolagus hispidus). The GPS-based sign survey method was used to look for indirect signs such as pygmy hog droppings, nests and hispid hare pellets and feeding signs. A total of 20 nests of pygmy hog were detected at three locations. Hispid hare pellets were found almost on all camp sites. Wet alluvial grasslands dominated by Barenga (Saccharum narenga) and Ulu (Imperata cylindrica) species under the two ranges are critical for the survival of the pygmy hog and hence Manas Wildlife Sanctuary’s authority takes suitable methods to protect it. The survey also received evidence for other grassland obligate species like hog deer (Hyelaphus porcinus), swamp deer (Rucervus duvaucelii) and the Bengal florican (Houbaropsis bengalensis).

The Manas River, which is a major tributary of the river Brahmaputra, splits into two rivers, the Beki and Bholkaduba, as it reaches the plains. Five other smaller rivers also flow through the national park which lies on a wide, low-lying alluvial terrace spreading out below the foothills of the outer Himalaya. These rivers carry an enormous amount of silt and rock debris from the foothills and this causes heavy rainfall leading to rock fragility and catchments with steep gradients. Alluvial terraces are formed comprising layers of deposited rock and detritus overlain by sandy loam and a layer of humus. The Terai tract in the South consists of fine alluvial deposits with underlying pans where the water table lies near the surface. The area contained by the Manas-Beki system gets inundated during the monsoons, but flooding does not last due to the sloping relief. The monsoon and river system are responsible for the formation of four geological habitats here, namely, Bhabar savannah, Terai tract, marshlands and riverine tracts.

The sanctuary is recognized not only for its rich biodiversity but also its scenery and natural landscapes. Manas lies on the border between the Indo-Gangetic and Indo-Malayan bio-geographical realms which gives it great natural diversity. The ecosystem of Manas supports three types of vegetation: semi-evergreen forests, mixed moist and dry deciduous forests and alluvial grasslands. The vegetation of Manas has tremendous regenerating and self-sustaining capabilities due to its high fertility and response to natural grazing by herbivorous animals. Much of the riverine dry deciduous forest is at an early successional stage, being constantly renewed by floods. Away from water courses it is replaced by moist deciduous forest, which is succeeded by semi-evergreen climax forest in the northern part of the park. Its common trees include Aphanamixis polystachya (hakhori bakhori or pithraj), Anthocephalus chinensis (kadamba), Syzygium cumini (jamun), S. formosum, S. oblatum, Bauhinia purpurea (kachanar), Mallotus philippensis, Cinnamomum tamala, Actinodaphne obvata. Tropical moist and dry deciduous forests are characterized by Bombax ceiba (semul or silk cotton), Sterculia villosa, Dillenia indica, D. pentagyna, Careya arborea, Lagerstroemia parviflora (Sida or Dhauli), L. speciosa (jarul or Pride of India), Terminalia bellirica (bauri), T. chebula (haritaki), Trewia polycarpa, Gmelina arborea (gamhar), Oroxylum indicum (toguna or bhuta-vriksha) and Bridelia spp. Much of the most valuable timber has been harvested.

The climate is warm and humid with up to 76 per cent relative humidity. It rains from mid-March to October with maximum rainfall during the period of the monsoon from mid-May to September flooding the western half of the reserve. The mean annual rainfall is 3,330 mm. November to February is relatively dry when the smaller rivers dry up and large rivers dwindle. The mean maximum summer temperature is 37°C and the mean minimum winter temperature is 5°C.

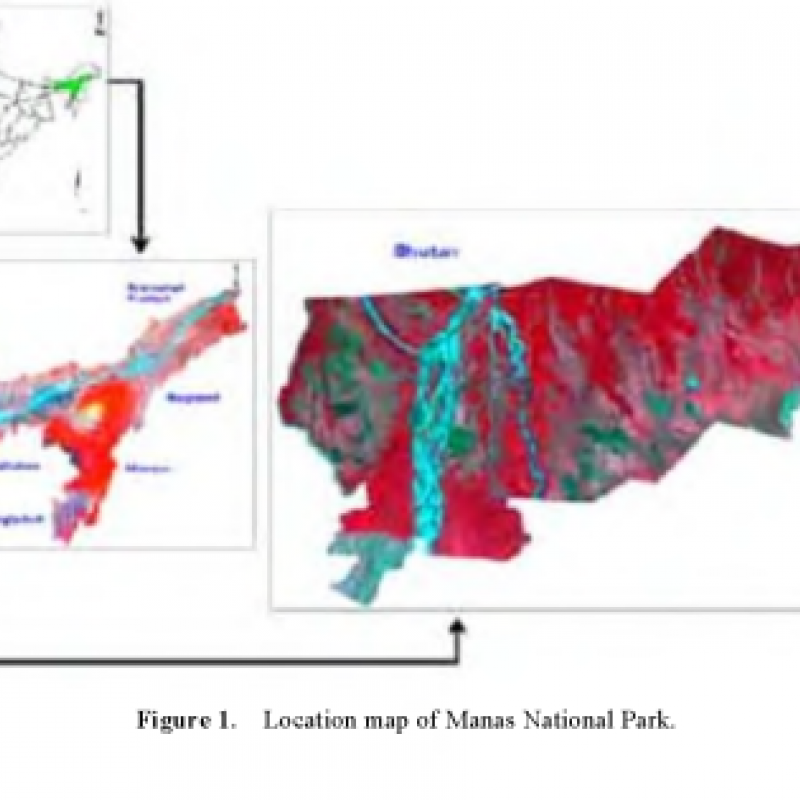

Covering an area of 39,100 hectares, the Manas Wildlife Sanctuary is part of the core zone of the 283,700 hectares Manas Tiger Reserve. The park is divided into three ranges. The western range is based at Panbari, the central at Bansbari near Barpeta Road, and the eastern at Bhuiyapara near Pathsala. The Manas River also serves as an international border dividing India and Bhutan. The northern boundary of the park is contiguous to the international border of Bhutan manifested by the imposing Bhutan Hills. It continues in Bhutan as the Royal Manas National Park and on the east and west less effectively by the Manas Tiger Reserve. Thus, trans-boundary cooperation is of paramount significance for its effective protection and security.

From 1988 to 2003 the Park was occupied by Bodo separatist groups. Part of their protest included campaigning for the restoration of their right to use forest lands, a separate province and for tribal autonomy. During this insurgency a lot of complications arose in the sanctuary. All the park’s rhinos were wiped out, while elephants, tigers and other wildlife were ruthlessly slaughtered, all of which caused a near-decimation of its wildlife. The insurgency years saw the killings of forest staff of various ranks, the poaching of several domestic elephants and destruction of 28 camps.

In the year 1989 gunmen from the Bodo ethnic group attacked Manas, including recently constructed offices and quarters as well as park facilities. Maintaining law and order was a challenge and local poachers wiped out most of the rhino, tiger and elephant population. Even herbivorous animals were prey to this poaching spree. Management of habitat activities like controlled burning of grasslands, de-silting of water bodies and prevention of livestock grazing could not be carried out and the overall quality of the habitat deteriorated. The downfall of Manas therefore traced a predictable pattern: the alienation of local communities, followed by breakdown of the government machinery, local extinction of sensitive species, and finally an irreversible change in the landscape and permanent loss of the knowledge needed to guide future treatment and corrective measures.

Once the situation restabilised, the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), working with the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) and the Assam Forest Department helped repopulate the park and re-establish it as one of the most exceptional wildlife parks in the world. A rhino reintroduction plan was devised in 2005 since the population of rhinos had almost been wiped out. Rhinos, elephants and other wildlife were brought back to the park from other parks. In 2003, when their insurgent bases in Bhutan just across the border became usable, the Bodo insurgents surrendered their arms and agreed to a pact with the government, which granted them a certain degree of autonomy in the Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC). Thereafter, considering the Park as their own territory, they were persuaded to protect it against intruders and to convince neighbouring villagers to adopt the same attitude.

The park was initially understaffed and underfunded, with inadequate equipment and infrastructure and no comprehensive conservation or interpretive strategy towards local communities. But as a result of the tribes’ cooperation poaching declined, tourism gradually restarted and it became possible to rebuild the park's infrastructure. The highlight of the recovery, though, has been the unique way in which the participation of local youth has been actively sought for the management of Manas and its buffer regions. The past sociopolitical situation in the region had forced many of the uneducated youth toward poaching and petty timber felling—the easy and perhaps only means available to earn money. Volunteer groups from the local NGOs Green Manas and Manas Bandhu slowly began to persuade local militants/youth to help conserve rather than destroy the park. After the formation of a stable local government, these youth were employed as conservation volunteers on a monthly stipend and ration. They assisted the forest department in surveillance and patrolling activities. With the help of national and international NGOs, some of the youth were also trained to act as nature guides for small ecotourism enterprises. Even though a part of Manas is still inaccessible due to armed insurgency, and poaching remains a concern, the recovering park can be called a ‘regained paradise’.

A WHC/IUCN mission visiting the site in early 2002 promoted the nomination of Bhutan’s Royal Manas Wildlife Sanctuary as a future trans-boundary World Heritage Site which would improve protection of the entire Manas ecosystem. This was revived by the 2008 WHC/IUCN Mission with renewed interest from Bhutan, Assam’s Chief Wildlife warden, the Indian and Bhutan offices of WWF, the UNESCO office in New Delhi, and the Indian government. Since poaching is a major issue in some parts of Manas, to check loss of wildlife habitat and curb poaching in the trans-boundary Manas landscape that straddles across India and Bhutan, conservationists in May 2015 have suggested joint patrolling by forest officials on both sides of the border.

IFAW volunteers are working with local communities around Manas to boost anti-poaching efforts and to train and equip rangers so that wildlife can flourish safely once again in this world heritage location. Under the ‘Save the Rhino’ campaign, rhinos have been regularly brought to Manas. These rhinos are either relocated from Pobitora Wildlife Sanctuary or Kaziranga. In order to prevent rhinos from escaping, since this puts them in danger, Manas National Park authorities wish to put up electric fencing so that rhinos do not get translocated.

Similarly, elephants too have been brought from other places. In 2011 there was a rare conservation success story that emerged from Manas National Park. This was based on the sighting of a rehabilitated elephant being accepted into a wild herd. The elephant, named Hamren, was among the five hand-raised calves relocated to Manas in January 2011 as part of the Elephant Reintegration Project—a joint venture of the Assam Forest Department and International Fund for Animal Welfare–Wildlife Trust of India (IFAW-WTI), supported by the Bodoland Territorial Council. The calf had been admitted to the IFAW-WTI run Centre for Wildlife Rehabilitation and Conservation (CWRC) in a severely injured and weak condition in May 2008 and was carefully nursed back to full health. This was also a matter of pride for the Sanctuary and the authorities. Human-elephant conflicts in the fringe areas of western part of Manas National Park have been noticed, so organizations like the Dolphin Foundation have done extensive studies to develop a strategy for controlling the problem.

The people living around Manas are dependent on its forest for their livelihood. Aaranyak, a leading bio-diversity group in Assam, has started a novel project to provide alternative means of livelihood to the people in the fringe areas of Manas National Park who have been dependent on the jungle for their daily necessities. The plan is to reduce people’s dependency on the jungle and forest and to encourage community participation in the conservation of Manas National Park through self-reliant economic activities in fringe villages. Aaranyak helps in the formation of Self Help Groups (SHG) by gathering the men and women of the area and trains them in food processing and weaving. Due to this initiative, people’s dependency on the forest has reduced and these SHGs also help Aaranyak with conservation activities in the forest. Hunting, which was common with Bodo and Adivasi communities living in the fringe areas of the Manas National Park, has been reduced. Aaranyak also organizes day long training programs in association with the Forest Department and Bodoland Territorial Council.

Women are active participants in these programmes. Women in wildlife areas are vulnerable to poverty and lead a life wholly dependent on forest resources. Limited access to basic infrastructure like roads, communication and electricity makes it difficult for women to access information, markets and services necessary to improve their livelihoods. Therefore, Aaranyak conducts these programs with the aim of providing women hailing from the fringe villages with an alternative and sustainable livelihood option, which is independent of forest resources.

In recent years they have conducted programmes on cultivating mushrooms as it is easy and profitable. Another advantage is that mushrooms can be cultivated round the year with two different varieties in summer and winter. WWF is another organization working on providing alternative employment to people living in the villages near Manas. The income of the residents here is mainly generated from two sources; agriculture and forest produce. Recognizing the need to generate alternative employment for the villagers WWF-India’s team from North Bank Landscape (NBL) began regular interactions with them in 2009 in collaboration with Manas Ever Welfare Society (MEWS). To provide them with a livelihood that does not depend on forests, WWF and MEWS helped construct a ‘Dairy Development Unit’ in the village. This activity is part of the initiative Indian Rhino Vision (IRV) 2020, which aims to increase the Rhino population in Assam to 3000. The International Fund for Animal Welfare-Wildlife Trust of India (IFAW-WTI) has also introduced green livelihood alternatives under the Greater Manas Conservation Project. They have introduced a weaving center providing women with looms and raw materials like yarn. More than 55 handlooms have been provided as of today: 8 in Polodobi forest village, 10 in Nabin Nagar, 11 in Sisubari forest village, 21 in Rangijora and 6 in Sourang. All of their products—from aronai (scarf) to gamusa (towel)—have a well-established local market, which ensures them an average income of 2000 INR per beneficiary every month. There is also a Multimedia Livelihood Project started by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund in Manas. Thus, along with wildlife even the livelihood of people in and around Manas has been taken care of, with the idea of protecting the forests from over-use.

Manas is now one of the most sought-after tourist locations in India and has gained prominence in other parts of the world as well. It is not only known for its flora and fauna but also for its rich culture, which includes the art, dance, food and music of the local communities.