Humble Beginnings

With a compact team of 5 producers, Bombay Doordarshan1 was inaugurated in Worli on October 2, 1972 – coincidentally on Gandhi Jayanti. The city’s cosmopolitan nature led to programming in 5 languages – English, Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati, and Sindhi. There were four major children’s shows– Santakukadi (Gujarati), Kilbil (Marathi), Khel Khilone (Hindi) and Magic Lamp (English). They were aired during evenings between 6:30 pm and 7:00 pm on weekdays, and on Sunday mornings. Producer Kunwar Sinha, ‘a news and current affairs man’ (Sinha 2017)2, and Mariam Jetpurwalla3 supervised all the English programmes including Magic Lamp. This Sunday morning fare initially had a simple format wherein Nandita, an anchor cum ventriloquist would appear with her glove puppet Tikku. Both Sinha and Jetpurwalla had no prior experience in children’s programming. Jetpurwalla explains, ‘Since no briefs were given to us… on how children absorb programming, we had to depend on teachers and entertainers who worked with children in order to shape the programme, although there was no consistent attempt at doing one kind of thing’ (Jetpurwalla 2017).4

Then entered a fresh batch of producers, including Shukla Das5, who had previously done a stint in public broadcasting abroad at WGTV, Georgia. Television in the US began in the 1920s, thereby giving the nation a clear head start in TV production including children’s content. Das was blown away by the American children’s classic Sesame Street6 and had also participated in their acclaimed Children’s Television Workshop (CTW)7. She was disappointed with the counterparts being telecast on Bombay’s Doordarshan for children. Her major complaints were that they ‘lacked continuity’ and became a ‘playground for performing monkeys’ (Kini 2017)8.

For the first two years at Bombay Doordarshan, Das specialized in documentaries and youth based shows. Then, in 1974, the then Director General V.S. Shastri finally handed her Magic Lamp. She was tasked with transforming it into a star programme for Bombay Doordarshan. In her words, she was given ‘six months’ time and a carte blanche to dream’. Das envisioned in Magic Lamp a ‘world for the Indian child’. She drew inspiration from Sesame Street’s spectacular universe, but insists her show was aimed at the ‘urban and contemporary child of Bombay unlike Sesame’s early audience of low-income black children’(Das 2017)9.

Turn Around and Enter Apple House

Six months later, the Apple House series was born. In it dwelled ‘Alu’ and ‘Phullu’, India’s own Ernie and Bert. Alu was a boy and Phullu was a girl. Both were playmates who stayed together. Personality wise, Alu would often make mistakes and get away with it, unlike Phullu, the perfectionist. Alu made mistakes only because he was creative; he was both a scientist and artist so it was inevitable for him to falter sometimes in his quest for knowledge. Characterization was an important element in Magic Lamp, as Shukla explains. She modelled Alu and Phullu’s personalities after their star signs – Pisces and Virgo respectively. The vibrant Apple House set in which they resided was designed by M.S. Sathyu10. The show, exploring concepts like friendship, sharing etc., was the most difficult one to do because of the abstract nature of these concepts.

An episode themed around Christmas, for instance, involved Alu facing a dilemma after not having money to get a gift for Phullu. His friends tell him that it is the thought that counts more than the gift. So Alu makes her a doll using old socks and buttons. Concepts like these would orient the child both to everyday and special situations (IGNOU n.d.)11.

Hulla Gulla Pathshala and Time for Sloppy

‘All the characters created for Magic Lamp had a reason, a raison d'etre to exist’, says Shukla Das (Das 2017).

While the Magic Lamp series began with Apple House, it quickly expanded to Hulla Gulla Pathshala or the Topsy-Turvy School, for portraying science tricks and fun-filled activities. The school was run by Alu and a core group of children working for the show, fondly known as Magic Lampers. It began with the catchy song ‘Hulla Gulla Pathshala Hulla Gulla! We love to dance; we love to sing! We love to make a many a thing! Hulla Gulla Pathshala Hulla Gulla!’.

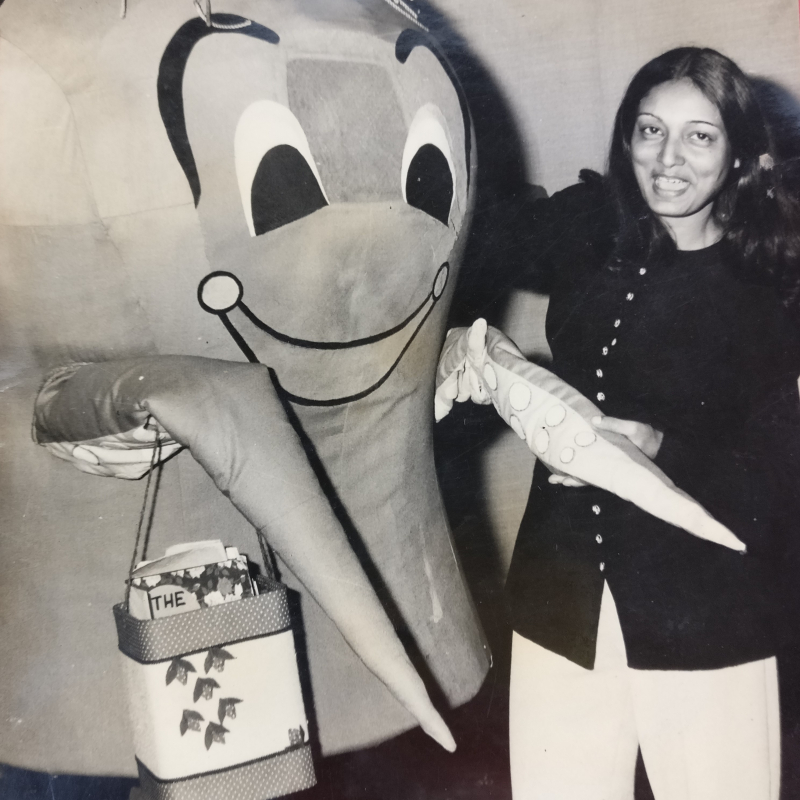

By this time, the show gained popularity with fan-mails pouring in by the dozen. Neither Alu or Phullu could carry so many letters, could they? Lo and behold, the show introduced ‘Sloppy’, the mighty Muppet akin Sesame Street’s Big Bird. Sloppy was an octopus, eight feet in diameter, and with eight long arms to carry the heaps of letters. The character was jointly conceptualized by Das and Mohini Vasvani, the show’s writer. Getting Director General V.S. Shastri’s approval for Sloppy wasn’t easy. Whenever Shukla strode across the corridors flanked by her assistants Rashmi Lamba and Rekha, Shastri would ‘just run away!’ (Das 2017). When he found himself facing the 8-foot oceanic muppet, he went deliriously, ‘No! No! Yes! NO!’. Shukla was in no mood to back out. She plonked Sloppy in front of Shastri’s door so he would be unable to get in until he had acquiesced! Once Sloppy was given the go-ahead, the show’s art director Bijon Dasgupta12 ultimately found a residence for him in a cupboard.

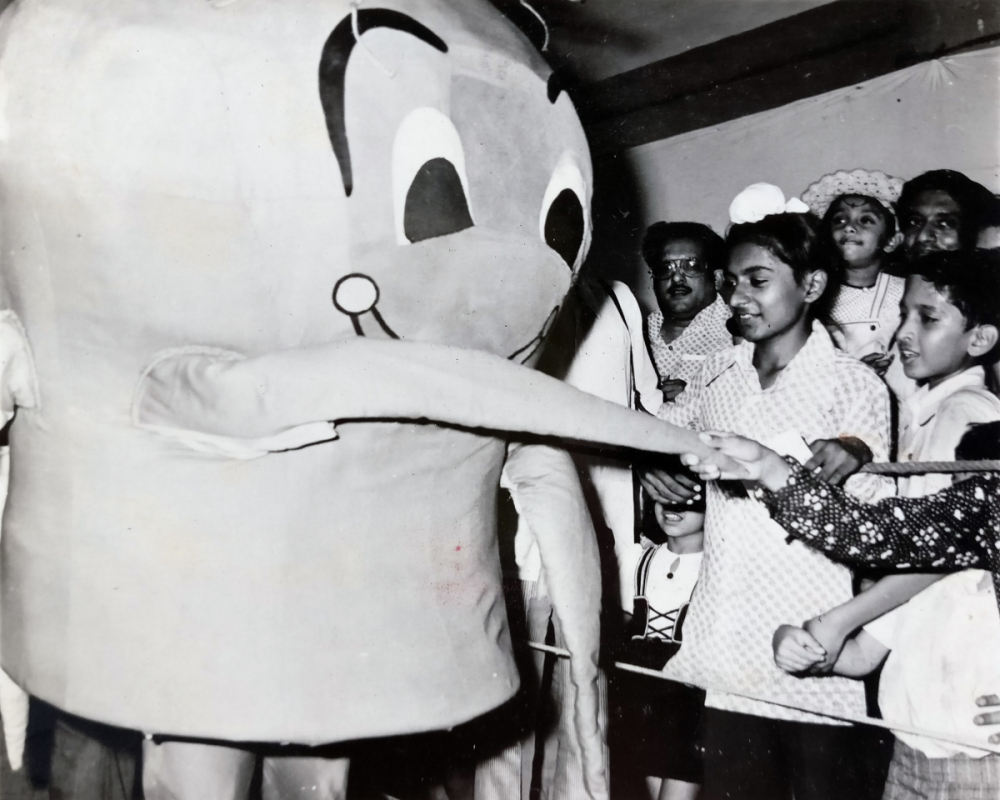

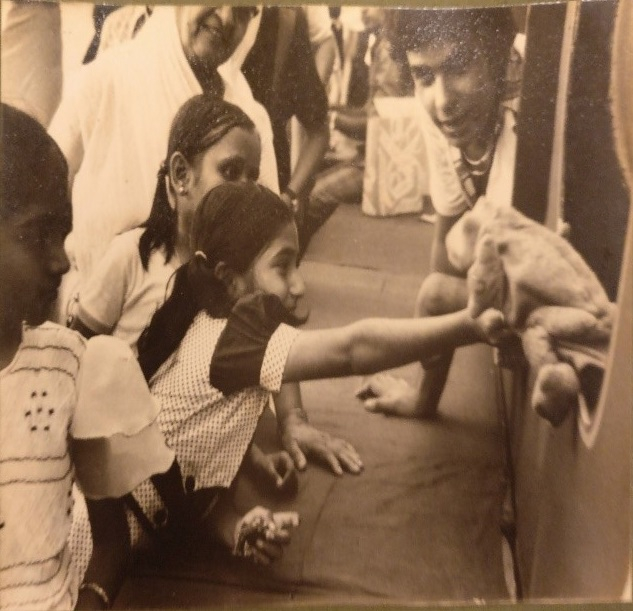

Sloppy became an instant sensation, gathering a legion of curious followers wherever it wandered. Be it during a school fun-fair, where he glided across a skating rink and jubilantly dance with screen legend Mehmood13 as children watched with rapt attention. On a visit aboard INS Vikrant14, a crane had to be arranged to hoist his gargantuan frame.

A Child’s Playground

‘They would joke… if the head of Shiv Sena, Shri Bal Thakerey, attempts to stop Magic Lamp or does anything to Shukla Das, an army of children would attack him!’ - Shukla Das (Das 2017)

The active participation of a child was an integral component of all the four children’s shows airing on Bombay Doordarshan in the 70s. Producers felt that involving children would result in better acceptability and self-identification and offer inspiration to child viewers.

Magic Lamp had a core group of children called Magic Lampers who turned up every Friday to rehearse the songs and dances, penned by writer-composer Barbara. The final shoot took place over the next two days. The idea of a recurrent batch of children for the show was taken from Boston based WGBH-TV’s live-action children’s show Zoom (1972-1978). The show sometimes entertained requests by child viewers by calling them to perform during the episodes. The famed film director and production designer Omung Kumar (Sarabjit, Mary Kom), for instance, was one such kid who did a snake dance. Children would stay up as late as one in the morning to celebrate characters’ birthdays on set.

The Apple House and Hulla Gulla series were engaging by themselves, however, Magic Lamp’s crowning glory was the Panna Clubs.

The Panna Mania

‘The whole idea was to break the glass boundary of television’, says Shukla Das (Das 2017)

Inspired by one of Jim Henson’s most famous creations Kermit the Frog15, Panna was a tiny glove-puppet imported from Russia. He was shaped like a frog and was christened by none other than one of the child viewers. His name means ‘emerald’ in Hindi, and for a while, he entertained audiences from within the confines of the television screen. Rashmi Lamba, a student of Mass Communication fresh out of college was hired to take Panna out of Doordarshan and into the streets of Mumbai. ‘My first outdoor project was for the Society for the Education of the Crippled16. Shukla told me to go out there with this little fellow in my hand and find potential sponsors. It was something I had never done! The people we met found us very interesting because we weren’t asking for money but wanted in kind’ (Lamba 2017)17. Rashmi convinced the ‘God of Advertising’ Alyque Padamsee18 to coin the slogan ‘Lots A Funa with TV’s Panna’ for the first activity.

|

An Excerpt: Panna’s Encounter with Spastic Children Two frog puppets stand face to face in an empty classroom. "Who are you?" asks the smaller one. "I am Panna. What's your name?" "Squeezmi", comes the answer and Panna rolls with laughter. "I am rather special:' says Squeezmi haughtily, "I jump about when I am squeezed up here." (She points to a vacuum pump on her head) "What is so special about that?" asks Panna. "You see Panna, the children of this school are different. They have disobedient hands and feet. . .." Squeezmi takes Panna around the centre for Special Education and explains the problems that spastic children face. She shows him a speech therapy session, then takes him to a nursery where children play with puppets like herself, specially designed to help them learn muscular coordination. Panna is fascinated and asks if he can stay back in the spastic children's doll house but Squeezmi has the last word: "You can't because you are not special like me." (Source: EGyankosh Unit 4 Writing for Television: Children; Author: IGNOU) |

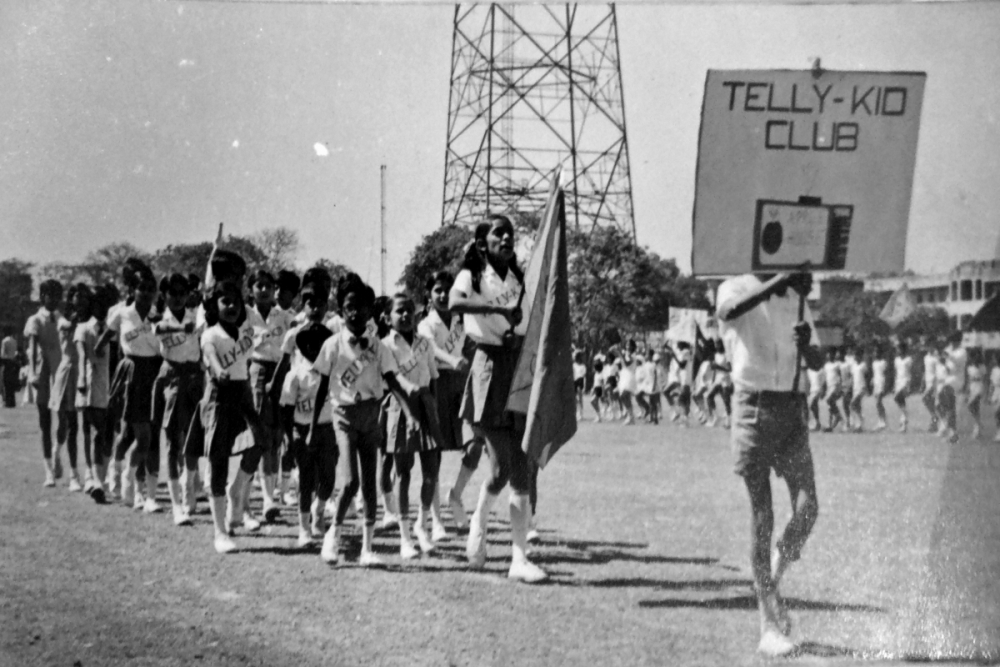

Panna Clubs’ objective was to harness the energy of children in contributing to the society and become future change agents. Panna himself would preside over the clubs and give out projects every alternate month. The Panna clubbers would comprise entirely of children between the age group of seven and twelve. The clubs would elect a captain and vice-captain for themselves without any adult interference. Through the years over 3500 Panna clubs were formed throughout Mumbai and Pune. Many highly engaging projects were organized. Some activities such as ‘Swim for the Blind’ or ‘Cards for the Specially Abled’ were socially driven and sensitized kids to the less privileged. There were projects like Save a Coin, in partnership with State Bank of India which encouraged children to open a bank account with five rupees. Then there was the annual Athletic Meet where the clubs would create their own team names, flags, and logos and compete in sporting events. Children from all sections of the society would unite. Das credits the extensive support of parents and college students throughout, whether in deciding the game or devising the rules etc.

Big names in the industry would look forward to being a part of Panna. The winning team of Sell Cards for the Blind, for instance, were rewarded an evening with actor Nargis Dutt19. The cards themselves were printed by Frank Simoes advertising agency20. Sam Balsara, presently the Head of Madison Group, was a product manager at Cadbury then and he would give free gift hampers for a line in the show’s credits saying ‘Grateful Acknowledgement’. ‘We had Apple House and Panna stickers, t-shirts and glasses all at a time when Doordarshan was not commercial’, boasts Lamba (Lamba 2017).

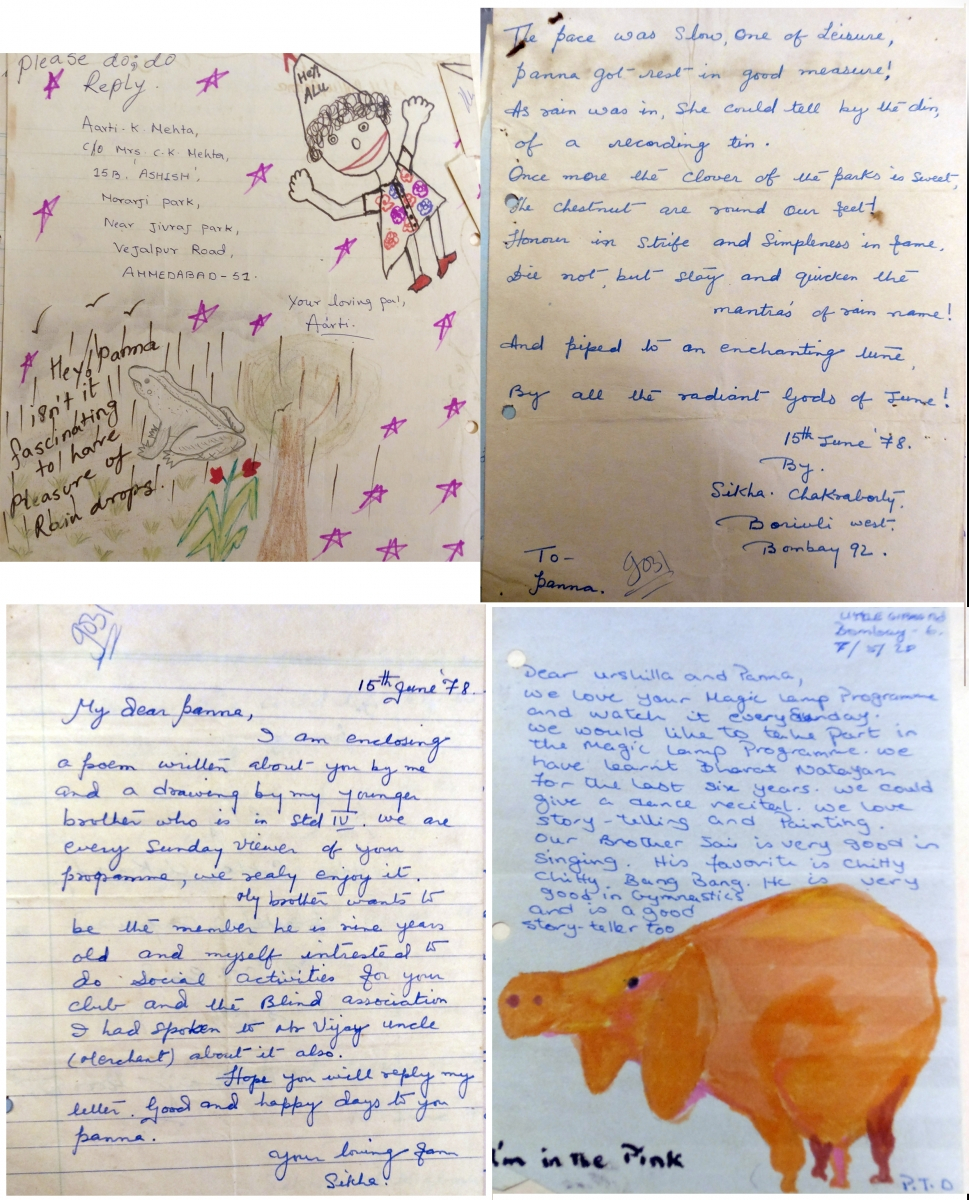

Children would write poems and stories and draw pictures dedicated to Panna in their letters. The Magic Lamp team also drafted letters to clubs that were inactive in order to get their response and attempt to revive them. Das recalls the time she received a poignant letter from one such club where the team captain had passed away. He had written to his Vice Captain to take over as Captain and lead their club to new heights (Das 2017).

Panna literally became an icon for Doordarshan – the Panna Club’s emblem was an image of the character popping out of the Doordarshan symbol. ‘The genius of Magic Lamp was to take Panna out of the box. Kids finally realized Panna was green in color and not black-and-white as he appeared on the television’, Rashmi reflects (Rashmi 2017). The Panna Clubs traveled beyond Mumbai and Pune through the exchange of recording tapes between kendras in different cities. Encouraged by its thriving popularity, Shukla wanted to make Panna into an All India Movement, however, Doordarshan then was not willing to take it on.

You Will Become a Famous TV Star

A major strength of Magic Lamp was to have ‘two-way interactivity’ with its audiences. On one hand, children were called on set to participate in activities (especially in Hulla Gulla Pathshala). On the other hand, the show’s characters stepped into the world outside (Panna Clubs). The final show to be introduced was the Star Quiz, which encouraged parents to watch the show. Here, a parent and child would pair up, with three teams competing with one another. The parent would answer questions on subjects meant for the child and vice-versa. The stars in question would be three of the puppets and muppets. Rashmi approves of Magic Lamp’s ‘participative rather than passive experience’ (Rashmi 2017). She later went to produce Zip Zap Zoom21 where she similarly roped in parents to boost the show’s credibility.

The Other (Magical) Worlds Magic Lamp

‘Magic Lamp had many worlds in it… as many worlds as a child needs’ - Shukla Das (Das 2017)

Magic Lamp had other, smaller worlds and characters too. Characters ‘Dhondu the Bondhu’ and ‘Moo-Cow’ acquainted Mumbai’s urban audiences with rustic life. Characters stopped by for a snack at ‘Nafisa’s Corner Shop’, run by Nafisa Aunty (Nafisa Jetpurwalla, Mariam Jetpurwalla’s sibling). Ronnie Screwvala22 was only college student then who played two characters – Dr. Ronnie and the Merry Monster, a spin on Sesame Street’s Cookie Monster. Rashmi adds, ‘Shukla and the writer Mohini had a brainstorm where they decided to name the monster character Merry Monster so children wouldn’t get scared. The character was a good monster who took away the fear of the child’ (Lamba 2017). In addition to the myriad of live-action segments, Magic Lamp included animated vignettes on road rules called Monu the Menace.

The Sweat and Toil Behind the Magic

‘When my assistants Rashmi and Rekha would go out into the field, I would tell them only one thing, “Going out there, don't come back with a No. You have to come back with a Yes… for everything..”’- Shukla Das (Das 2017)

Children’s shows then were largely recorded and transmitted live, leaving no room for error. All the four children’s shows were allotted one day in total to record. This was barely enough. Considering these constraints, Magic Lamp was an exceptionally ambitious project. Through her sheer resolve, Shukla convinced Doordarshan for more recording time and got 2-3 assistants when her contemporaries could afford one. Nischint Hora, who initially worked as a Production Assistant on the show and much later as a Producer lauds Shukla’s tenacity, saying, ‘Magic Lamp involved lots of thinking and effort. Each of concepts involved 7-8 days of absolute work. Shukla had to fight her way through the bureaucracy’ (Hora 2017)23. Rashmi recalls the 16-hour workdays when she would return home early morning when the milk was being delivered.

Unlike Sesame Street, the show that inspired it, which received $8 million grant in its first year, Magic Lamp worked on a very limited budget. Most of the crew members were freelancers, with the core team of Shukla, Mohini, assistants Rashmi and Rekha juggling multiple responsibilities. ‘We had no such concept as voicing for television… all these things were conceived from scratch. We trained the voices and puppeteers, although they were never as sophisticated as those on Sesame Street’, notes Das (Das 2017).

A Brief Encounter with Sesame

‘Magic Lamp was truly inspired by and modelled on Sesame Street. You compare Ernie and Bert with Alu and Phullu. Or Kermit with Panna, Big Bird with Sloppy. Likewise, Cookie Monster and Merry Monster… There was no system of broadcast copyright in India then. Yet one cannot hide the fact that the show was adapted’, Rashmi explains when the question arises if Magic Lamp was an unofficial adaptation of Sesame Street (Lamba 2017). She clarifies immediately that the show wasn’t a blatant recreation or copy. Shukla admits the strong influence of Jim Henson’s beloved creations on her Indian counterparts. Although she clarifies that Sesame Street started out as a show for lower-income black children while hers targeted the urban children from relatively affluent backgrounds within Bombay. Furthermore, she insists the characters finally conceptualized for Magic Lamp had only a reflection of the characters of Sesame’s. These statements suggest that Magic Lamp could be one of the earliest examples of a localized Indian children’s television show.

Were the makers of Sesame Street happy when they learnt about Magic Lamp? It seems so. Norton Wright, in-charge of Sesame Street’s international productions, and Edward L. Palmer, vice-president of Research at Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) and a consultant on Sesame Street, were in Film and Television Institute of India (Pune) for a training programme which Shukla happened to attend. ‘They wanted to see what kind of shows India does, and when they saw Magic Lamp, they were amazed, exclaiming, “We never took it here. How did it come here?! How did you do it?!”’ (Das 2017).

Shukla additionally wanted to demonstrate the potential of India animation, which boasted of just two major short films – The Banyan Deer (1957)24 and Ek Anek Aur Ekta (1974)25. Magic Lamp too had experimented with animation through the road-rules-based vignettes titled Monu the Menace. For the presentation, Shukla brought a cartoon figure of a little flower with slits its eyes. She pushed a white paper with tear drops drawn on it through the slits to make it look like the flower was crying. ‘They (Wright and Palmer) were impressed because we were doing something in an unbelievably limited centre… not only in terms of budget but also in terms of facilities, in terms of cast and crew. We had no trained puppeteers or muppeteers… They were impressed by the fact that we were pulling it off!’, Rashmi states fervently (Lamba 2017).

After a seal of approval from Sesame Street, all Magic Lamp needed to move beyond Bombay and capture the hearts of all of India’s children was Doordarshan’s backing.

The Magic Goes Away

‘I have so many memories of waking up early and watching TV on Sunday. Those days were good, yaar. TV was new, we were just discovering it. It was wonderful. We hardly had any channels to surf… jo aa raha tha woh hum dekhte they (we watched whatever came on air). We only had DD then. I used to get up early on Sundays to see Magic Lamp on Mumbai Doordarshan. I remember the puppets Aaloo and Phuloo.’, Bollywood actor Aamir Khan, in an interview with Harneet Singh for Indian Express (Singh 2012)26.

In the 70s, Doordarshan kendras existed merely in eight Indian cities27, becoming a National Broadcaster in 1984. Until then, the kendras within these cities exchanged tapes with each other and shows like Magic Lamp could travel beyond Mumbai and Pune. To mature the series, especially the Panna Clubs, into an All India Movement, Shukla would require extensive infrastructural support. Doordarshan could not envision such a possibility at that stage. As the channel catered to the masses at large, whether as a regional or National Broadcaster, it didn’t commit to being a specific age group or genre. It rather functioned like a general entertainment channel. Secondly, children’s programming received a lower priority. Producer Nischint Hora shares that, ‘Children’s programmes on Doordarshan are either dumped on the producer along with other things or happen on National Days, where “it has to done”’ (Hora 2017). Besides, most children’s shows were shot and transmitted live because greater recording time would be reserved for variety shows, quizzes, and dramas. They were terribly short-staffed. Nayana Dasgupta, the creator of the Gujarati children’s shows Santakukadi, admits that the main producer would conceptualize, develop as well as implement the project usually with one assistant at their service (Dasgupta 2017)28. Magic Lamp’s team admirably overcame many of these challenges, inspiring at one point the entire Bombay Doordarshan staff to participate in the Panna activities. Yet, as Rashmi aptly puts it, the show was ‘too ahead of its time’ (Lamba 2017).

When Julian Scott from Britannia approached the subsequent Directorate General PV Krishnamoorthy proposing music CDs of the original compositions from Magic Lamp, he was flatly refused. Also rejected were any attempts by private companies to commercialize the show through merchandising. The Directorate General obstinately declared that the DAVP [Directorate of Advertising & Visual Publicity]29 will bring out the book and the record. However, Shukla was not convinced by his undertaking. ‘I know the level of DAVP. I know what kind of paper they’ll use. I know what kind of artwork they’ll use. I do not want it brought up by them’, she replied firmly (Das 2017). She claims Amar Chitra Katha30 went to make a record but it never saw the day of light. Since the episodes of Magic Lamp and its contemporaries were shot on 2-inch tapes generally used for live television, no archival footage exists today.

After giving seven years of her heart and soul to Doordarshan, Shukla Das left the network in 1979. Magic Lamp was briefly pulled off air leading to much consternation among its audiences. Shortly after that, the Panna clubs too dissolved. The show’s cast and its puppeteers, mostly college students, moved on. Magic Lamp was temporarily revived in the 80s with Nischint Hora as the producer. Albeit, it was stripped of its fabulous identity. Hora laments, ‘When DD became National, Magic Lamp turned from weekly to fortnightly. Once all the English programming on DD National stopped, the show was gone’ (Hora 2017).

More than two decades later, Galli Galli Sim Sim, the official Indian adaptation of Sesame Street launched on DD National in 2006. It has remained on air ever since and reaches out to a staggering 14 million viewers (Indiantelevision.com Team 2017)31. While the success of this show is definitely worth applauding, we must not forget to celebrate the show with similarly lofty ambitions but beaten by its time, a show that created a magical world for the Indian child in Mumbai in the 70s. Magic Lamp exists today merely as still photographs and in the memories of its makers and its audiences.

Notes

1. Bombay Doordarshan or Doordarshan Kendra, Mumbai, was the second kendra (centre) launched in India by National Network Doordarshan. It currently telecasts its programmes under the brand name DD Sahyadri.

2. Kunwar Sinha in a discussion with the author, December 23, 2017

3. Mariam Jetpurwalla is best known as the scriptwriter on Shankar Nag’s renowned adaptation of RK Narayan’s Malgudi Days.

4. Mariam Jetpurwalla in a discussion with the author, November 5, 2017.

5. Shukla Das is a former Senior Vice President at Sony and Star TV. She is also an independent filmmaker by profession. She is currently based in Pune where she works as a professor at FLAME University.

6. Sesame Street is a puppet-and-Muppet based educational programme launched on PBS (Public Broadcasting System) in 1969. The show has an astounding 48-season run with over 4500 episodes produced. It currently airs on PBS and HBO.

7. Sesame Workshop (SW), formerly Children’s Television Workshop, is an American not-for-profit organization that has produced several educational programming for children including Sesame Street.

8. Kini, S. 2017, January 03. ‘Revisiting 'Magic Lamp': Allu, Phullu, Sloppy and Doordarshan's enchanted Indian childhood’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from https://thereel.scroll.in/819127/revisiting-magic-lamp-allu-phullu-sloppy-and-doordarshans-enchanted-indian-childhood

9. Shukla Das in a discussion with the author, October 19, 2017.

10. A Padma Shri award-winning film director and art director best known for his directorial film Garam Hawa (1973).

11. IGNOU, n.d. ‘Unit-4 Writing for Television: Children’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from http://egyankosh.ac.in//handle/123456789/22079

12. Bijon Dasgupta has worked as an Art Director on movies like Khal Nayak (1993), Mohra (1994), Gupt: The Hidden Truth (1997), and Umrao Jaan (2006).

13. Mehmood Ali (1932-2004) was an Indian actor, singer, director, and producer with over 300 films to his credit. He was best known for his comic roles.

14. The first aircraft carrier built in India.

15. Kermit the Frog was introduced in 1955 and has starred in various muppet productions including Sesame Street (1969-present) and the Muppet Show (1976-1981).

16. A Mumbai-based not-for-profit organization providing formal education to physically handicapped children and adults.

17. Rashmi Lamba in discussion with the author, October 19, 2017.

18. Alyque Padamsee is a notable theatre personality and ad filmmaker. He was once the head of Mumbai-based advertising company Lowe Lintas.

19. Nargis (1929-1981) was one of the most well-known actors in Hindi cinema, best known for playing the lead in the Oscar-nominated film Mother India (1957).

20. A homegrown Mumbai-based ad agency launched in 1967

21. A live-action children’s show launched on ARY Digital in Dubai

22. Cofounder of Upgrad and former founder and CEO – UTV Group

23. Nischint Hora in discussion with the author, November 24, 2017.

24. The Banyan Deer was the first major initiative undertaken by the Films Division of India to produce a full-fledged animated movie in color format. It was released in 1957.

25. Ek Anek Aur Ekta or "One, Many, and Unity" is a traditionally animated short educational film released by the Films Division of India. It was released in 1974.

26. Singh, H. 2012, April 29. ‘Man on a mission - Indian Express’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/man-on-a-mission/942863/0

27. Delhi (1959), Mumbai (1972), Srinagar (1973), Amritsar (1973), Pune (1973), Calcutta (1975), Madras (1975) and Lucknow (1975)

28. Nayana Dasgupta in discussion with the author, October 18, 2017.

29. The nodal agency of the Government of India for advertising by various Ministries and organizations of Government of India, including public sector undertakings and autonomous bodies.

30. One of India's largest selling comic book series, the publishing house was founded in 1967.

31. Indiantelevision.com Team. 2017, August 04. ‘DD to dub Galli Galli Sim Sim in more Indian languages: Sahu’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from http://www.indiantelevision.com/television/tv-channels/terrestrial/dd-to-dub-galli-galli-sim-sim-in-more-indian-languages-sahu-170803

References and Further Reading

Kini, S. 2017, January 03. ‘Revisiting 'Magic Lamp': Allu, Phullu, Sloppy and Doordarshan's enchanted Indian childhood’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from https://thereel.scroll.in/819127/revisiting-magic-lamp-allu-phullu-sloppy-and-doordarshans-enchanted-indian-childhood

IGNOU, n.d. ‘Unit-4 Writing for Television: Children’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from http://egyankosh.ac.in//handle/123456789/22079

Singh, H. 2012, April 29. ‘Man on a mission - Indian Express’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/man-on-a-mission/942863/0

Indiantelevision.com Team. 2017, August 04. ‘DD to dub Galli Galli Sim Sim in more Indian languages: Sahu’. Retrieved December 19, 2017, from http://www.indiantelevision.com/television/tv-channels/terrestrial/dd-to-dub-galli-galli-sim-sim-in-more-indian-languages-sahu-170803