‘The variety of dance items and movement patterns within today’s Kathak are witness to its syncreticism - this is not an art form that can be traced to a single origin but a recent and ongoing fusion of a number of north Indian performance traditions.’ - Margaret Walker

Although it is commonly accepted that Kathak originated in the temples of ancient India, it is not longer than some 300-400 years back that we find traces of ‘kathak-like’ dances, where the dance resembles the present form it has. It is eventually only in the 19th century in Awadh, that the form begins to come closer to its recent shape. The Kathaks family, evidentially from Bindadin Maharaj on, greatly enriches the form, composing nritta and abhinaya compositions, that form a part of not only their repertoire, but also the repertoire of the courtesans, who worked in close association with the Kathaks family, and played a major role in the history of Kathak.

In the 16th-17th centuries we begin to find evidence of dance and music forms that resonate in some aspects with modern day Kathak, albeit in a different vocabulary prevalent at the time. We do not find mention of the word ‘Kathak’ in these sources, suggesting that Kathak is yet to be condensed into its present form. But what we find are very useful descriptions of the different desi dance styles of those times, some of which are strikingly similar to the performance of present day Kathak. Through a discussion of these music, dance and drama forms, we find the narrative of Kathak slowly emerging, with its fair share of continuities and discontinuities.

The association of the word Kathak with the present day dance form takes place only in the twentieth century, and before that we find that Kathak was actually the name of a community associated with music and dance, commonly as teachers and accompanists of the dancing women and also performers themselves (Walker 2014).

Due to the land provided generously by the Mughal ruler Akbar, important temples came up in the regions of Vrindavan and Mathura, amongst others, attracting followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and Vaishnava Bhakti in large numbers. The poetry coming from these regions frequently contained important terminologies and descriptions that today help us understand these dance styles.

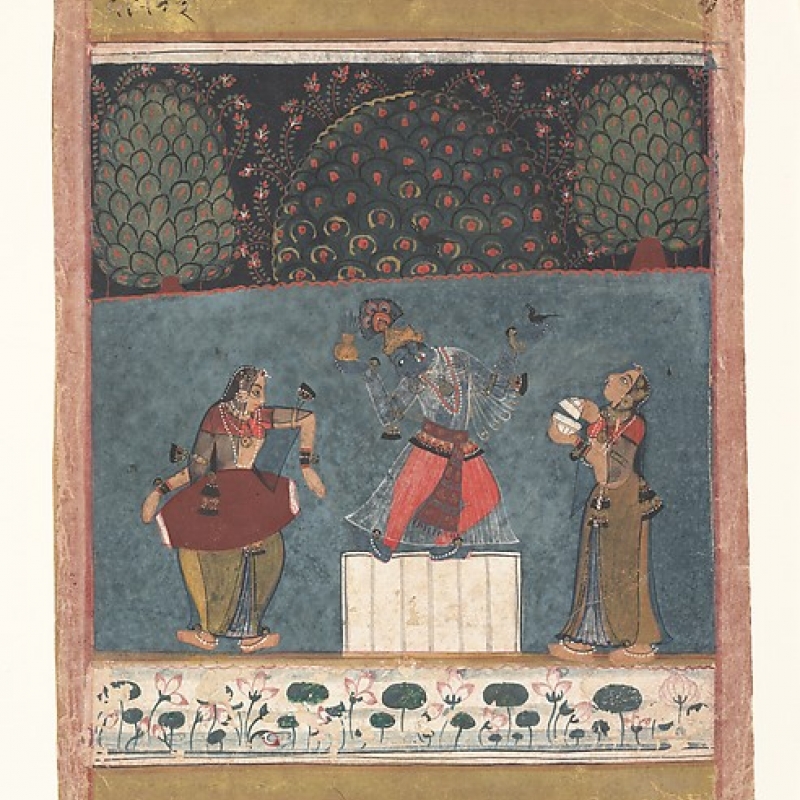

The followers of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who were devoted to Vaishnavism and in particular celebrated the human-divine love of Radha and Krishna, were dedicated to the Madhurya Bhava, or the emotion of sweetness, an inadequate English translation of the phrase. The influence of Gita Govinda (12th century) by Jayadeva was nothing short of a revolution, as it spread a feverish Bhakti sentiment, adding flames to the existing raw passion. It thus provided literary and aesthetically rich content for the development of several performance traditions across the Indian subcontinent, like Rahas or Ras, Kuchipudi, Sattriya, Ankia Nat, Kathakali, Bhavona, Ras Lila, Rahas, and so on. The Bhagavata Purana, especially the 10th book, was another text that carried extensive descriptions of Krishna Lilas (Shivaprakash 2017).

These texts provided the poetic and performative inspiration to create immersive dance dramas based on the life of Krishna. The Bhaktas (a general term used to describe a devotee of any God) expressed emotions towards their God through various dance, dance-theatre, and music forms. Bhagavatas, who were specifically the devotees of Vishnu, tied anklets on their feet and performed. Anklets and ghunghroos are found in many big and small Bhakti performance traditions and most classical dance forms today make use of ghunghroos indicating a very strong influence of Bhakti on nearly all classical dance forms. One finds this also in the predominance of playing out mythological stories through performance, an integral part of the Bhakti tradition.

Kathak uses the most number of ghunghroos, going up to 200 bells on each foot owing to the extensive use of footwork in its form. The inspiration of Krishna as a dancing god is very popular in the Bhakti movement and carries over to modern day Kathak in the form of numerous thumris, kavitts and gats dedicated to the dancing Krishna. The name Natvar, literally meaning the perfect dance/dancer, is assigned to Krishna.

…..

As mentioned earlier, the Bhakti imagination provides a window into dance traditions of those times, and gives us an opportunity to find traces of present Kathak in several different traditions spread over space and time. Consider this very interesting and beautiful composition from Sur Sagar, a collection of the works attributed to the 16th century Bhakti poet Surdas:

Patur chatur sab ang nirat karat, desi suddh ang gai

ta ta thai thai ughatat hain harshi man

urap tirup lag dat tat- tat- tat thai ta thai thai

let gati man ta ta thai thai hastak bhed

…

gati sudhang nrityati braj nari

…

nirtat mandal madhya Nandlal

urap tirup lag dat tat- tat-tat thai ta thai thai

…

nritya karat udghat sangit pad

(qtd. in Trivedi 2012:173)

Patur seems to be the medieval term for a ganika, a professional woman proficient in music and dance, an association Kathak carried till Indian Independence, when courtesans were still practicing dance and enjoyed patronage (Trivedi 2012). Along with her, everyone is dancing or doing nirat, probably a local way of referring to nritya. Nirat, or nirtat seems to be a regional or local way of addressing dance and both are very commonly found in the medieval and early modern literary sources of dance that have survived. This is an important indication of the desi or ‘folk’ associations of Kathak as more terms find resonance in local and regional sources than from the Sanskrit shastras. The most direct association of this term with Kathak is Pandit Bindadin Maharaj’s composition from the 19th century Niratat Dhang, in which he has described the way (dhang) of doing dance (niratat), its mood and its different technical compositions.

Additionally, we find a description of a variety of body movements or ang in the above poetry such as dhilang, urup, tirup, dat, and lag, which were probably executed in the performance of Ras and other dance-drama forms of the Braj region, suggesting the deep influence of Ras in Kathak (Trivedi 2012). Urap and tirup are movements of jumping, and so is dhilang wherein the dancer leaps and lands on the ground as described in Tuhfat al-Hind (1775), written by Mirza Khan ibn- i Fakhr al Din Muhammad. Jumps and leaps retain their legacy in Kathak, especially in Benaras Gharana, which carries an acrobatic element in its performance presentation.

We also find mention of Ta ta thai thai, the foundational bols of Kathak today that are organised into tatkar, a type of footwork, and also come in nritta compositions. They also seem to be a popular set of pneumonic syllables in the 16-17th century and feature in several literary compositions as indication of dance.

Coming back to the poem from Sur Sagar, another important feature is the art of recitation. The recitation is recognised through the use of the word ughat/udghat which is a variation of the word udghattana, literally meaning ‘to strike’ (Trivedi 2012). Could this explain the (striking) attitude in the delivery of bols in Kathak today?

According to Mirza Khan, ughat are a combination of syllables set to tal (time cycle) and usually comprise of five syllables: ta,di,thu,na,ti/tai(thai) (qtd. in Trivedi 2012), all of which are used in Kathak today. He then adds that the dancers recite these syllables themselves before proceeding to doing them, a practice solo Kathak dancers have retained till today even on the stage. Udghat, thus also alludes to the act of speaking the composition, apart from doing it. A contemporary version of ughat would probably be padhant (speaking the composition). The repertoire of bols seem to be restricted to ta ta thai thai at this time and probably expanded slowly with time. Today there is an immense variety of bols that has come very far from the initial ta ta thai thai.

A very important reference to a desi dance form we get through this poem, and others like it, is sudhang, a colloquial way of saying ‘shuddha ang’ or pure dance. This has been elaborated in Tuhfat al-Hind (1775), where four distinct dance styles are mentioned as being prevalent in the 17th century. These are:

- Tand (Tandava)

- Las (Lasya)

- Chain or Chindu

- Sudhang (Shuddha Ang)

(qtd. in Trivedi 2012)

We also find a description of the performance in Tuhfat al-Hind which is certainly very valuable in understanding the performance format, and also the influence of these desi presentation formats on later day Kathak. The description is as follows:

…the dance performance involved four people - the singer (goyanda or khwananda), the dancer (raqqas), the cymbal player (tal-dhari), and the mridang player (mridangi). The goyanda recited Ughat (rhythmic patterns in a loud voice), and also marked time by clapping his hands and slapping his feet. The mridangi reproduces these with the same rhythm, stress and emphasis (usul-o vazan). Then the raqqas danced the same piece in a similar manner. The time cycle was marked by the tal dhari. Dance performances were held in the makan-i raqs, also called rang –bhum (rang bhumi)

(qtd. in Trivedi 2010:111)

This is an important description as Kathak today borrows from these desi traditions the format of presentation in terms of musicians and padhant. Trivedi makes a point that though we do not find a mention of these forms in the later source, there is suggestion of some continuity through the mention of a thai thai nach in Mir Amman’s Bagh-u-Bahar (1802-03 AD). Thai Thai, as discussed above as well, are bols that are a part of the contemporary Kathak repertoire.

While tandava and lasya are still present in contemporary times (as concepts if not in the exact same form as before), it is the forms chain and sudhang that need more elaboration, as this terminology is quite uncommon now. Mirza Khan describes chain as a style characteristic of ‘bending, twisting and vacillating motion in walking’ (qtd. in Trivedi 2012). This description, though short is very valuable. One of the aspects of Kathak is a stylised way of walking, also known as gat. In the gat, a dancer holds a certain pose with her body and walks in that pose in a variety of stylised gaits. For example, in payal ki gat, the dancer walks in different ways showcasing the payal (anklet); and in ghunghat ki gat the dancer walks and holds different kinds of ghunghat (veil). Additionally, the vilambit laya (slow tempo) of Kathak, which showcases slower pieces like thaat also involves a little bit of stylisation in walking and holding the gestures.

Mirza Khan also adds that chain is the style he would attribute to Krishna, ‘who after his triumphant conquest of serpent Kaliya danced on its hood to the music of his flute’. The historian Madhu Trivedi has studied this and has noted that probably this Leela of Krishna was later incorporated as Kaliya Mardan Gat, which is danced in Kathak even today (2010). However, Margaret Walker examines the same source and suggests that this is not probable (2014). Thus, there is a difference of opinion amongst scholars on this connection.

Sudhang or Shuddha Ang is described as a dance form where the ‘units of tal’ (probably syllables) are performed with graceful and suggestive body postures and movements. It is interesting that Surdas’ Shatpadi Nachat Sudhang Sri Nand Nandan is a very common invocation in Kathak today. As the phrase suggests, Krishna (Nandan) is dancing sudhang (nachat sudhang) or pure dance. This is an important literary/oral historical reference to the dance forms of the 16th century. Krishna is very clearly described as doing ‘sudhang’, a desi dance form prevalent in those times. The presentation of sudhang bears a striking resemblance to the presentation of present day Kathak, suggesting the prominent influence of sudhang on the evolution of Kathak. Natvar or Krishna is a very important figure in Kathak, with several members of the older generation of Kathak going as far as say that an informal name of Kathak could be Natvari Nritya.

Natwari Gat in Kathak is attributed to Krishna. It is possible that the gat is an offshoot of the dance form called chain or chindu, which consisted of a highly stylised way of walking and bending. However, chain is certainly not the only influence, and should be seen in context with other probable influences like Jakkadi, the dance of Persian women in the Mughal courts. Jakkadi finds documentation in the texts of its times like the Nartana Nirnaya (16th century Sanskrit text) by Pandrika Vitthala. Bose situates Nartana Nirnaya as an extremely important textual source to understand the history of Kathak (1999). In it, Vitthala describes how the women hold the edge of their costume and dance softly with not a lot of movement, singing Persian songs accompanied by gesture.

It is commonly accepted that Kathak has been heavily influenced by Persian song and dance traditions. Bose has made an observation about chakkars in Kathak, which could also have a Persian influence. She argues that while ‘all classical styles use the chakkar in some capacity, the movement is never fast enough nor is it sustained enough to achieve the aesthetic form it does in Kathak (1991).’ Indeed, the chakkars have a very special place in Kathak and contribute to its unique aesthetic. Jakkadi then becomes another very important source to see how and from where the origin of Kathak took place and thus becomes a strong contender to be an early ancestor of Kathak.

The ‘bending, twisting and vacillating motion in walking’ of chain, along with Jakkadi, perhaps contributed to this characteristic fluidity of movement in Kathak. The influence of a variety of forms on Kathak needs to be seen as an amalgamation rather than attempting to trace a singular linear source. History is never linear, but a coming together of multiple narratives overlapping each other. So it is with Kathak, where we see one of the finest examples of syncretism, where Indo-Islamic, rural and courtly, margi and desi, aesthetics and traditions merge to form a seamless presentation of music, dance and literature co-existing simultaneously.

……

Till now we have covered a brief journey of Bhakti movement and its influence on dance, but the difference in past and contemporary terminology on dance remains unresolved, and we still do not find all the aspects of Kathak in one single art form. What remains with us is a realisation that present day Kathak evolved to its current form in the past 150 years with its rising popularity in Awadh, the contribution of musician communities, hereditary tawaifs, the Kathaks family and the several desi and Persian traditions mentioned in the first part of the article. Nowhere has the dance itself been described as Kathak, and its history needs to be weaved through the multiple layers of narratives available to us.

Moving ahead with our search for its origins, the texts written during the 19th century offer fairly reliable and valuable information on Kathak. Keeping in mind that the terminology of texts like Natyashastra (2nd century AD) and Abhinaya Darpan do not fully tally with the repertoire of Kathak, it is not possible to understand the history of Kathak without reading texts from this period as it is commonly understood that Kathak attained its present identifiable form in Awadh in the 19th century.

Margaret Walker (2014) has studied five books between 1852-1877 that discuss music and dance practices of those times.

- Ma ‘dan al- Musiqi (1856) - Muhammad Karam Imam

- Ghuncya-yi Rag (1862-3) - Muhammad Mardan ali khan

- Saut al- Mubarak (1851-2) -Wajid Ali Shah

- Bani (around 1876) - Wajid Ali Shah in Matiaburj

- Saramaya-yi Israt (1875) - Sadiq Ali Khan

From these texts we find several important descriptions that are similar to the present day repertoire of Kathak. To begin with, we find the name of performers with the surname ‘Kathaks’- Ma ‘dan al-Musiqi lists nine performers with this surname, and it is noteworthy that not all of them are dancers or ‘Kathak’ dancers:

- Prashaddu Kathak of Benaras - singer

- Jatan Kathak of Benaras - sarangi player

- Ram Sahai Kathak of Handia- dancer

- Beni Prasad of Benaras - dancer

- Prasaddoo Kathak of Benaras - dancer

- Lallooji Kathak - dancer

- Prakash Kathak - dancer

- Durga- Prakash’s nephew - dancer

- Mansingh-Prakash’s son - dancer

(qtd. in Walker 2014:66-67)

It is also mentioned that Durga and Mansingh were both ‘proficient in bhav’ (Walker 2014).

Handiya is identified in oral history as the place where the first generation of Kathaks comes from, though Ram Sahai is not mentioned in the Lucknow Gharana family tree. Many dancers and instrument players come from Benaras, as we see, and we also find the possibility of a migration of dancers from Benaras to Lucknow for patronage in the 18th century. Additionally, there is mention of female dancers, especially those of Benaras and their style of singing, dancing, and Bhav Batana (For more, see Walker, 2014:84-88). Saramaya yi Israt mentions that ‘Prakash Kathak’s son is an accomplished master of nritta and is very famous (qtd. in Walker 2014).’

Saramaya yi Israt also refers to Kathaks as a group of expert performers of dances such as ‘parmilu’. Kathak dancers would identify here that parmelu or pramelu is one of the pieces in the technical repertoire of Kathak even today. But here parmilu has been identified as a kind of dance itself, unlike today when it is a part of a larger dance form.

Ma ‘dan al-Musiqi tells us that:

‘…among the dancers Lallooji (probably Hiralal) and Prakash Kathak have distinguished themselves in Gat Bhav and Artha Bhav. They are Ustads in Lucknow. Durga, nephew of Prakash, was a prodigy but died young. Now Mansingh and his younger brother (Thakur?), both sons of Prakash are good dancers, and they dance, according to the tradition of their family. (Walker 2014:102)

But the important focus here is that there seems to be a concentration of dancers in Awadh, who came from desi dance styles and might have performed in courts on occasion.

Other sources too confirm that Prakash Kathak was regarded as a dancer of great repute and calibre, and gave his attendance in court performances too. Madhu Trivedi finds that Prakash Kathak came from the Rasdhari community, who practiced the devotional dance-theatre form of Ras Lila or Rahas, that depicted stories of Krishna and carried a certain acrobatic element in their dance. Thus, Ras is ingrained in present day Kathak as some of its ancestors, such as Prakash, themselves came from this tradition. Whether it is the predominance of Krishna in its abhinaya or the acrobatic aspect of the Benaras Gharana, there is an influence of not just male but also female Ras dancers. Prakash Kathak has probably been mentioned as Prakash ‘Nartak’, a dancer in the court of Asaf-ud-Daula (reign 1775-1797). Walker has however argued that it is not possible to ever know with certainty the relation between the Kathaks and Ras Dhari community, and the Ras Dhari themselves claim no consanguine or other affiliation with the Kathaks.

Names aside, what we also get is the description of the repertoire of these performers. These texts discuss compositions like tora, paran, parmilu, tukra, and gat, which are all part of Kathak’s repertoire today. Walker has noted that there are 14 gats described in Saut al Mubarak, the names of which are also repeated in Madan al Musiqi and Ghuncya-yi Rag. Madan al Musiqi mentions the Krishna gat, which is practiced among the Kathaks. Saramaya yi-Israt mentions a mardani ki gat, which is danced by Kathaks and Bhands where the dancer folds his arms across his body and stamps his feet in the rhythm of the drum (qtd. in Walker 2014).

Most of the other gats seem feminine in nature and performance, such as fariyad ki gat, janasheen ki gat, ghunghat ki gat, and belonged to the repertoire of the professional dancing women, while the male Kathaks had a different repertoire.

There are indications in these five texts that the repertoire of male dancing was different from the female dancers’ repertoire in many ways. The dancing of the women artists was soft, amorous and lyrical whereas nritta bols largely belonged to Kathaks and Bhands. The parmelu is seen as having a higher status and it is performed by Kathaks. The gats seem to have been divided between men and women. There are three gats for men: the plate gat, plate and bowl gat, and mardani gat. In Krishna gat in Madan al Mausiqi, the dancer would take spins on the ground on his knees which is performed in the Ras Lila and fits well into the picture because many dancers in Wajid Ali Shah’s court came from the Ras tradition. The fluidity and swaying aspect of the courtesan dances seems to suggest thaat and gat in particular, which involve the swaying body movements, and very subtle movement of different body parts, like wrists, eyes, neck, feet, etc.

Out of the several gats prescribed for women, here is a description of janasheen ki gat, known as the nikas ki gat today:

…the right hand is positioned above the head, with an open palm’s distance between the head and the hand. The right elbow should be at the earlobe level. The left arm should be straight like an arrow, the chest should be raised…Fingers and wrists of both hands should be swinging softly and flexibly, and the hands closed like fists should keep opening on tat and ta (Khan 1884:165 Sarmaya-i Ishrat qtd. in Walker 2010:285)

This gat has been described at the janasheen ki gat in the text. Today, we do not keep the fists closed, but tat and ta are syllables stressed upon in gatnikas even today. This pose is now the most characteristic pose to instantly identify Kathak dance. (Put dancing girl 4 image)

It must be noted that even though these texts discuss the dances of Shiva and other Hindu gods, they do not ascribe any religious interpretation to this particular pose (Walker 2014). Nowadays, it is very common to hear this pose being interpreted through religious imagery as showing Krishna’s feather or as Shiva-Parvati pose.

There is also a mention of ghunghat ki gat. This gat seems to be popular and finds mentions in Madan al Musiqi, Saramaya yi Ishrat, and Bani. From the pictures we observe that at that time the courtesans wore layers of dupatta, and actually held the veil (ghunghat) in their fingers while performing the gat.

Today, it is not possible for a Kathak dancer to dance with so many layers of clothes especially at a fast pace. Furthermore, the dance repertoire is no longer divided between men and women and both men and women perform the graceful, soft and slow dancing of the courtesan as well as the rhythmic nritta (pure dance) of the male Kathaks in the same recital. The subtle body movements, kasak, masak, jumbish, etc, are all legacies of the women dancers that survive in a toned down format today.

Additionally, Wajid Ali Shah has described five gats in his book Bani, which are influenced by the Kaharva community (qtd. in Trivedi, 2010):

Maccheri gat

Bahanga gat

Thainga gat

Lahanga gat

Pankha gat

The fanning and water carrying activities of the Kaharva community become an inspiration for these gats (Trivedi 2010). Today, nav ki gat (boat) is performed often by dancers, in which the dancer imitates the action of rowing a boat; daily activities of rural life like fetching water from the well, going to bathe in the river and so on, also form part of the dance.

There also seems to be a continuity between the Persian Jakkadi in Akbar’s court, to the ‘shuffling gliding stylised’ steps of the courtesans in Delhi and Awadh in the 1700s, to the 19th century nautch. The gat, thaat, nikas, chakkar, slow dance of body movements, also matches the description of the treatises and definitely today’s Kathak repertoire (Walker 2014). The dancers are described as wearing clothes in layers that flow when they move, with the dupatta taken in multiple layers.

The professional women artists commonly had surnames like Bai and Jaan: Gauhar Jan, Siddheshwari Bai, Akhtari Bai (Begum Akhtar), Zohrabai Ambalewali, were some of the famous and established courtesans of the twentieth century. Their repertoire contains priceless thumris, dadra, and other such compositions, that have survived till now as the courtesans preserved and upheld the art traditions through their practice, thus becoming star recitalists. Many of them changed their surname to Devi during and after the Anti-Nautch Movement, in order to gain a more respectable status.

These women dancers however are not from the community of Kathaks. But we also know from records, paintings, diary entries, censuses, etc., that a majority of the dancers and singers were women, also contributing as musicians. Pallabi Chakravorty provides insight into the world of these female artists or tawaifs:

…unlike respectable married women at the time, tawaifs were literate and educated, enjoyed the legal right to own property and to inherit from their female relatives. Many managed to amass quite large fortunes principally through receiving gifts from wealthy male patrons and admirers. They were capable not only of singing and dancing, but also of reciting poetry, discussing politics and teaching young men manners and refinement…association with a famous tawaif could increase a man's reputation and social standing, certainly he would be able to network with other important men at her establishment. (Chakravorty 2008)

Bindadin Maharaj (d.1912), who was living and practicing in Awadh and was closely associated with courtesans, played a crucial role in developing the abhinaya ang of thumri. It is part of the family legend that he wrote more than 5000 compositions. The compositions that survive today can be recognised by his signature name ‘Binda’ in them. He is believed to have been a great devotee of Krishna, and wrote several compositions dedicated to him. He was also the teacher of the star performer tawaifs of their times Gauhar Jan and Zohrabai Ambalewali. Trivedi writes about the different kinds of bhav required in an expression piece that were further enriched by him:

Sabha Bhav

Ang Bhav

Arth Bhav

Nayan Bhav

Bol bhav

Nritya Bhav

Gat Bhav

Till today, thumri-dadra and bhajans written by Bindadin Maharaj are taught in dance classes and performed during recitals. They have largely survived through oral transmission and Pandit Birju Maharaj made an effort to collect Bindadin Maharaj’s works and publish them. Though the book is out of publication, it can be found with some members of the family. Bindadin Maharaj’s thumris are known to be melodious, intensely emotional and very rich in shringar (romance).

This association with the tawaifs would only last for a couple more decades as by the 1930s there was a strong mobilisation of society against these dancing women who were accused of decadence and loose morality, which thus left the repertoire in the hands of the Kathaks family. They then became the sole guardians, authorities and leading practitioners of the art form. In the wake of declining patronage and the absence of tawaifs, who used to be the leading and influential performers of their times, the Kathaks family came to the forefront and emerged as strong players in the journey that Kathak would henceforth take from the 1930s to the present popularity and status of Kathak.

The epicentre of the eventual exclusion of hereditary female performers from arts was Madras, 1893. The movement initially began with a discussion on Devadasis who were temple dancers, though not entirely temple bound always. Their dance was called Sadir, or Desi Attam, which was later re-named after some changes as Bharatanatyam. The general disdain for the decadent world of women artists was on grounds of loose morality, sexual promiscuity and sexual exploitation. However, instead of focussing on eradicating the evils of exploitation, it was the women who were slowly eradicated from the mainstream performing circuit, while problems of sexual exploitation of dancers continue even today in various forms. The approach, which should have preserved the dancer and the dance, actually preserved only the dance but let go of the dancers who had for generations upheld and disseminated the dance form.

The dialogue against the decadent art world slowly spread its ripples up in the North too and by the early 20th century the tawaifs were also targeted for their practice. The large number of Muslim artists in the North Indian performance practices and the amorous nature of the courtesan repertoire were very easy to malign in the wake of a nationalist politics that was seeking to refashion a morally righteous ‘Indian’ identity in the face of colonial onslaught.

This political stance is perhaps understandable in the moral context of those times when the national freedom movement was gaining momentum and social reformers were mobilising the society; however, it also cost several courtesans their professions, who were pushed into prostitution and slavery. Many of them turned to singing in the film industry, and it is a lesser known fact that courtesans and artists associated with the courtesan tradition formed one of the first generations of films, building the film industry as singers, actresses nad dancers. Many of the rich and established courtesans also became producers, opened their own production houses and sponsored films. Famed actress Nargis’ mother was the famous courtesan Jaddan Bai, who was also one of the earliest music composers in the films. Dancer Roshan Kumari, who performed the iconic dance sequence in Satyajit Ray's Jalsaghar (1958), was the daughter of courtesan Zohrabai Ambalewali, who was learning from Bindadin Maharaj of the Kathaks family. It is indeed a fascinating thread of historical connections.

Walker (2014) makes an incredible point that the marginalisation of female performers was quick to permeate in the social psyche since it did not question any of religious/ritual traditions of Hindus, as opposed to Sati and child marriage which were deeply grounded in religious beliefs and validated by religious sanction. The marginalisation of tawaifs did not require the middle class to question any of their existing religious beliefs which made this reform more comfortable than others which required intense religious debate.

It is also during this time that music and dance are separated into strict divisions. The repertoire of the tawaifs was one where singing and dancing flowed seamlessly into each other, adding to the richness of the performance. The abhinaya and gestures of dance enhanced the expression of the singing and the same artist sang and danced as part of the same performance and not as separate acts. We also find an abundance of female musicians in paintings from the medieval and early modern period (see image gallery 2).

However, with the systematic marginalisation of the tawaifs, the dance repertoire was labelled as being much more indecent in comparison to singing. Perhaps, it is easier to find devotional connotations in singing, but the dancing body with its suggestive and seductive movements immediately strikes as more sensuous than devotional to conventional sensibilities, making it more vulnerable to be attacked as indecent.

As Vidya Rao has said in her interview for this module, when the body of a woman comes in front it is much more difficult to handle as opposed to just a voice. Dance was connected to tawaifs who were reduced to prostitutes, and the scales of power shifted in favour of hereditary male practitioners. This ostracisation of female hereditary performers created an empty space, which was soon to be filled by non-hereditary women coming from all kinds of backgrounds. This new entry of women was marked by its own challenges, as the dance was associated with the decadent world of tawaifs and it was commonly believed (and is still believed in some cases) that women from ‘respectable’ families do not dance.

Even today, many parents are likely to teach their daughters Bharatanatyam or Odissi since they have a history of temple dance, but not Kathak which is so obviously linked to the courtesan salon. This gap of professional female artists was slowly filled by women from non-dancing families, from either middle class or elite family backgrounds. These women faced a lot of social backlash owing to the ill repute of the dance world, but they paved the way for not just future dancers, but also streamlined the organisation of dance into institutions that would make the learning of dance a more democratic and accessible space for the whole society.

Leila Sokhey, or Madame Menaka as she is popularly known, came from one such family with no hereditary background in dance and took up dancing with the help of the support of her husband. She founded Nrityalam in 1941 and invited senior hereditary Gurus like Sitaram Prasad, Acchan Maharaj, Lacchu Maharaj and Ramdutt Mishra. She introduced a three-year dance programme in Kathak, Manipuri and Kathakali.

But even before Nrityalam it was Nirmala Joshi who founded the Delhi School for Hindustani Music and Dance in 1936. She invited Acchan Maharaj to teach at her school and several future leading figures of Kathak like Sitara Devi, Kapila Vatsayayan, Reba Vidyarthi and so on, all learned from him. Later Joshi was an important part of founding the Bharatiya Kala Kendra in 1952 in New Delhi and when she became the secretary of Sangeet Natak Akademi, she handed over the functioning of BKK to Sumitra Charat Ram, another arts administrator from an elite non-arts family background. Lacchu Maharaj, also credited with the iconic Bollywood dance sequences of Pakeezah and Mughal-e Azam, founded Nritya Niketan, where one of his notable students was Rohini Bhate, who would later become a leading Guru herself (Walker 2014).

From what we have seen, there are more resonances of present day Kathak in late medieval and early modern sources, than in the temples or Sanskrit texts of ancient India. These early modern and modern sources provide very valuable material to understand our immediate past, which establishes a clearer evolution of Kathak, as opposed to a simplistic linear narrative that jumps from the ancient period to Mughal courts to the present proscenium stage so neatly without undertaking the complexity and multiplicity of narratives present in history.

References

Bose, Mandrakanta. 1999. ‘Dance at the Crossroads: An Early Source of Kathak’. In Studies in Hindu and Buddhist Art, edited by P.K.Mishra. Delhi: Abhinav Publications.

Chakravorty, Pallabi. 2008. Bells of Change: Kathak Dance, Women and Modernity in India. Calcutta: Seagull

Shivaprakash, H.S. 2017. ‘Bhakti Movements: Texts, Contexts and Performance’. Course taught at School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Delhi: January to May.

Trivedi, Madhu. 2012. The Emergence of the Hindustani Tradition: Music, Dance, and Drama in North India 13th to 19th Centuries. Delhi: Three Essays Collective

———. 2010. The Making of Awadh Culture. Delhi: Primus Books

Walker, Margaret E. 2008, India’s Kathak Dance in Historical Perspective. New York: Routledge

———. 2010. ‘Courtesans and Choreographers: The (Re)Placement of Women in the History of Kathak Dance’. In dance matters:Performing India, edited by Pallabi Chakravorty and Nilanjana Gupta. 279-300. New Delhi: Routledge