Focus on Chishtiyah and Related Orders

Sufism is a fashionable term these days, especially among the urban elite who often assume that visiting a Sufi dargah (shrine), listening to qawwalis (form of devotional Sufi music) or reading the poetry of Rumi or Amir Khusrau is akin to becoming a Sufi, or is at least an antidote to the present-day stressed out life. But a careful study of the history and literature of the Sufis may compel us to strive for knowledge and experience much deeper than the ‘trendy’ Sufi culture. In fact, even a mere study of the history of Sufism may not be enough, as the celebrated author Idries Shah says, ‘...the Way of the Sufis cannot be understood by means of the intellect or by ordinary book learning... it cannot be appreciated beyond a certain point except within the real teaching situation, which requires the physical presence of a Sufi teacher.’ Since it’s a very vast subject, this module on Sufi literature of South Asia should be seen only as an effort to introduce some historical and conceptual trends the Sufis have followed in the region through their writings and poetic compositions. Included here are a few articles, video interviews with scholars and practitioners, a timeline, and some other useful resources that will help you begin your journey through south Asian Sufism. But to do justice to the subject, you need not stop here. The journey is endless.

Defining the terms

The title ‘Sufi Literature in South Asia’ demands that we first try to define some of these terms: ‘Sufi’, ‘literature’, and ‘South Asia’. 'Sufism' or tasawwuf, the mystical dimension of Islam, has been defined in multiple ways depending on its practitioners and the historians of Islam. Some orthodox believers consider Sufism as a bid’ah or cultural innovation that is outside the fold of canonical Islam since, according to them, the Prophet Mohammad (May peace be upon Him) or the Quran does not sanction it. But some others consider it very much part of Islamic faith and practice. No doubt, the word Sufi or tasawwuf does not feature in the Quran or the hadith (Prophet’s traditions). Nor do the prescribed methods of the five pillars of Islam (Iman or faith, salah or prayers five times a day, fasting in the month of Ramazan, zakat or alms-giving, and Hajj pilgrimage), have any direct indication to the ‘spiritual’ or emotional dimensions of religious practice. And this is one of the reasons why some Muslims or Islamists do not find the practice of Sufis legitimate.

So where did the Sufis or Sufism come from? The Arabic word suf means wool, and the early mendicants in Arabia or Central Asia wore long, coarse woollen garments. The term Sufi or Sufism probably did not originate in Islamic texts, but was coined by Western Orientalists who perceived Islamic society through the binary of ‘moderate’ Sufis and ‘fundamentalist’ Wahhabis, whereas such a divide did not really exist. Even today, many believing Muslims, especially those not exposed to Wahhabi or puritanical forms of Islam, may not recognize this difference, since for them the spirit and the practice of their faith are very much intertwined.

Of course the Sufis believed in the essential pillars of Islam, but also contemplated on the problems and deeper meanings of life, questioned the prevalent dogmas and disparities of society, and brought people together with the message of love and equality. In some cases, they went into self-exile due to persecution from the clergy and the ruling class in response to their critique. They mostly disowned material possessions, and moved around from place to place looking for spiritual contentment. They tried to develop their mental faculties through contemplation and meditation, and achieve higher spiritual states. In many cases, they became links or bridges between contrasting cultures, religions and viewpoints through dialogue and mediation. Some were also associated with miraculous powers of healing and resolving people’s hardships, which is why the graves of some Sufi saints are still visited and venerated by people in need. But this culture of ‘tomb veneration’ too orthodox Islamists view with incredulity, even wariness, as they consider such practices innovative and thus un-Islamic, even though they may approve of the historical role the Sufis played in the spread of Islam in South Asia.

However, it is not easy to decide who can technically be called a true Sufi. In fact, some practitioners prefer not to be called a Sufi at all. They refer to themselves as ‘we friends’ or ‘people like us’, or friends in a halqa (circle, gathering). Some belong to, or are initiated into, a formal silsila or institution of lineage and perform specific rituals and spiritual exercises handed down to them via strict teachings, while others may simply have gained knowledge through secondary sources or independent study and remain busy in their regular worldly lives. There are also those who make it a profession by being hereditary caretakers or sajjada nashin (lit. the one sitting on a seat) of a particular Sufi’s grave, conducting prayers and making talismans on behalf of the visiting devotees and so on. Some believe that only a follower of Islam can be a Sufi while some others are open to people of any faith to join their halqa or circle. There is no central authority anywhere to certify who is or is not a Sufi. For our purposes, we would like to broadly focus on Sufis who have contributed to the body of mystical literature in South Asian Islam.

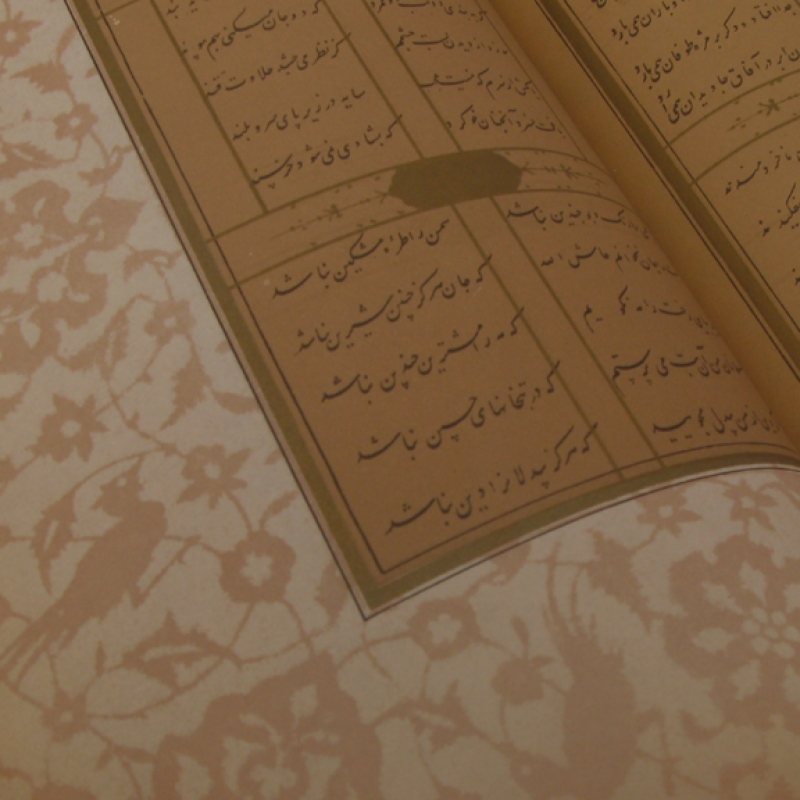

But how does one define 'Sufi literature'? Literature in any language or society is the spoken, performed or written text or idiom that usually follows certain poetic or grammatical parameters to communicate human emotions, philosophical thoughts, or simply, a story or historical information. Its purpose could range from entertainment and artistic communication to propaganda, chronicling and religious devotion, among others. So what really is the purpose of Sufi literature? How is it, if at all, different from the larger body of Indo-Islamic literature? Is it literature composed by the Sufis or for the Sufis? Or about the Sufi? Or any the above? In that regard, a big dilemma, at least for our purpose, is: whom to include as a Sufi writer/poet and whom to exclude, because after all, the making of any refined art or poetry can be a mystical experience, irrespective of what religion or cultural background the artist comes from.

One finds many different types of expressions in the Sufi literature composed all over the world, as we will discover through this presentation. According to Laleh Bakhtiar, ‘The Sufi, through creative expression, remembers and invokes the Divine order as It resides in a hidden state within all forms. To remember and to invoke, in this sense, are the same: to act on a form so that that which is within may become known. The Sufi thus re-enacts the process of creation whereby the Divine came to know Itself.’[i] In a way, through creativity, the Sufis attempt to invoke the Quranic expression where God said ‘I was a hidden treasure. I desired to be known, so I created the universe’. Following this, a large mass of Indo-Islamic poetry and prose in many languages could be classified as mystical or Sufi. But here we try to focus on a few specific poets or writers who represent prominent silsilas, literary/philosophical ideas or socio-political movements.

Even though South Asia (which today includes countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and Maldives etc.) has historically been perceived in different ways, including with titles like Bharatavarsha or Al-Hind (after the river Sindh), its boundaries have always been changing. Moreover, due to its Sufi links, the region cannot be seen disconnected from Central Asia or the larger Persianate world. The boundaries between South Asia and Central Asia were rather porous in the pre-modern times, which is the reason why one could also use the term Indo-Persian for the culture and literature under discussion. The Indo-Persian character of South Asian culture is also characterized by a wide variety of local languages and dialects that have been central to its evolution—almost every language, such as Punjabi, Sindhi, Bengali and Malayalam, to name a few, has been used by the Sufis to express their feelings over the last 800 years. Moreover, since South Asia is home to a wide variety of ethnic and religious identities, it may not be appropriate to restrict ‘Sufi literature’ to something that is produced only by Muslims—many non-Muslims have also been practitioners of Islamic mysticism and its literatures.

Arrival of Early Sufis into India

Before a discussion of the early Sufis that arrived in India, one needs to look at the early days of Islamic mysticism in Arabia or the larger Persianate world. It is difficult to say who the very first Sufis were, although many believe that the Prophet Muhammad Himself conveyed mysticism to Hazrat Ali (ibn Abi Talib), his cousin and son-in-law, from whom it was later passed on further to the imams (Islamic leaders). According to another account, the word Sufi may have come from as’hab as-suffa or poor people residing/sitting on a platform outside the mosque at Madina.[ii] According to Ali Hujwiri, an early authoritative Sufi writer, the Prophet Muhammad Himself said: ‘He who hears the voice of the Sufi people and does not say aamin (Amen) is recorded in God's presence as one of the heedless’. Due to his acclaimed role, almost all Sufis across the world trace their lineage back to Hazrat Ali. But it is really in cities like Basra, Kufa, Damascus, Cairo, and Baghdad, along with the deserts of Arabia, Sinai and Mesopotamia where the Sufi movement took root and flowered. It is said that one of the first Muslim mystics may have been Hasan Basri, a preacher and theologian who died in 728 CE (although Owais al-Qarani, a contemporary of the Prophet, is also said to be a mystic and a martyr, according to some). The town of Basra, where Hasan was born, is also famous for the first woman mystic, Rabia al-Adwiya (born 717 CE). Another mystic, Malek ibn Dinar (d. 748 CE), was a disciple of Hasan Basri.

The region soon started seeing the emergence of mystics like Ebrahim ibn Adham (d. 780 CE) in Balkh, Abu Yazid Bestami (d. 875 CE), Junaid Baghdadi (d. 910 CE), and Mansur al-Hallaj who was executed for uttering "An-al Haqq" ('I am the Truth') in 922 AD. Brief biographies or anecdotes about these mystics are found in much later compilations, but they themselves do not seem to have composed any literary texts. Al-Solami (d. 1021 CE) was the author of the oldest surviving collection of Sufi biographies, whereas Abu Naim (d. 1038 CE) wrote Ornament of the Saints, which was the main source of Muslim hagiology, especially for later authors such as Fariduddin Attar.

These mystics soon started travelling to farther lands, including India where, interestingly, the first known treatise on Sufism was written in Persian by Ali al-Hujwiri. Born in 990 CE in Hajvare near Ghazni, Ali travelled all over the Islamic world from Syria to Turkestan and from the Indus River to the Caspian Sea, meeting a large number of shaykhs (scholars of the Islamic sciences), before finally settling in Lahore, Punjab, and wrote Kashf ul-Mahjub ('The Revelation of the Veiled'). The object of this book, according to its translator Reynold A. Nicholson, ‘is to set forth a complete system of Sufism, not to put together a great number of sayings by different shaykhs, but to discuss and expound the doctrines and practices of the Sufis. The author’s attitude throughout is that of a teacher instructing a pupil.’

Even though Lahore could be considered an extension of the larger Persianate or Islamicate world of the time, Kashf-ul Mahjub really set the stage for South Asian Sufi literature, which does not simply comprise of poetry or theosophical speculation, but discusses mystical problems through illustrations drawn from personal experiences. This has remained one of the most popular books of tasawwuf among Indian Sufis. Even Nizamuddin Aulia of Delhi is quoted to have said that ‘the one who does not have a (spiritual) master will find a master by the blessing of reading this book’. In one of its chapters, ‘Concerning the doctrines held by the different sects of Sufis’, Al-Hujwiri enumerates the twelve mystical schools and explains the special doctrine of each, although Nicholson is doubtful about whether these formal schools actually existed previously or were invented by the author to systematize the knowledge of Sufism. But al-Hujwiri definitely did not belong to any of the specific Sufi silsilas or orders that later took root in India.

Although the da’wa (invitation) of Islam seems like the primary reason for the Sufis’ arrival from Central Asia into India, there were other factors too. The Mongol invasions between the 12th and 14th centuries drove millions of people from Central Asia and the Turkic region to the comparatively safe haven that was India at that time. Among the migrants, while the more powerful ones established the Delhi Sultanate, the first Islamic rule in India, others, such as the humble Sufis settled in rural and urban India, distanced from the rulers, to spread their message of reform at the grassroots level. But besides the fear of the Mongol invasion as a reason for their migration, one cannot ignore the curiosity evoked by India’s image as the land of wonders, fakirs and esoteric practices, among the Sufis and other wanderers from Central Asia.

Surely, the early dialogues between Muslim mystics and Indian sages did help in the evolution of newer spiritual practices, theories and rituals, some of which is also reflected in the Indo-Persian literature produced by the Sufis and other authors.[1] Accounts of various Sufis such as Baba Farid (Ganj-e Shakar), Nizamuddin Aulia or Mohammad Ghaus of Gwalior inform us of what dialogues and practices they shared with Yogis.[2]

To put the arrival of the Central Asian Sufis in India in a better historical context, one also needs to keep in mind that the region of Central Asia was a land of Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and ancient animistic practices when Islam arrived there (before it spread further to India). Thus, Islam practiced in Central Asia had already been coloured in the local cultural norms that comprised of polytheism and icon-veneration, which paradoxically it desisted. For instance, the Chishti Sufi order, before coming to India, had its early development in Central Asia imbibing at least some pre-Islamic practices and iconography.[3]

Some other early Sufis that came to India from Central Asia followed orders like Suhrawardiya, Kubravyia, Yasavyia and Qalandariya, etc. These had rather informal identities and did not have very fixed associations with particular lineages–many of their members were following two or more orders. The Naqshbandiyas came much later, probably in the 16th or 17th century. Interestingly, many Sufis, including the Chishtis, and their followers in South Asia consider Shaikh Abdul Qadir Jeelani (d. 1166 CE in Baghdad) as their spiritual master and qutb or axis, due to the popularity of his legends and spiritual powers. His followers also call their order the Qadiri silsila which has influenced Muslims all over South Asia as well as in Southeast Asian countries.

The Chishtiya Silsila

At the start, the Chishti order did not have a formal identity—its members practiced an amalgam of several ideas and rituals that were followed in the Qalandariya and Yasaviya orders. A Syrian scholar Abu Ishaq Shami (d. 940) came to Chisht, a small village in Herat, Afghanistan (where some remnants of the Ghorid period still survive), and sowed the seeds of what later became the Chishti silsila. One of the first Sufis in that lineage to have travelled from Chisht to India was Khwaja Moinuddin (b. 1140), who settled in Ajmer after moving all over central Asia and some parts of north India, including Delhi. He was initially a Malamatiya Qalandar and may have followed some animistic rituals and practices. As mentioned earlier, the Central Asian region had older traditions of Buddhism and pre-Buddhist animism when Islam arrived there. Over the years, Islam went through a process of assimilation with Buddhist and other traditions, the Muslim mystics being the chief agents of this experience.[4] In many cases, the Sufis were imbibing traditions which one may not be able to call Islamic, such as asceticism and ‘annihilation of self’ (fana-e nafs).

During his journeys in Central Asia, Khwaja Moinuddin met a person called Sheikh Ibrahim Qandosi who initiated him into mysticism. It is said that the impact of Qandosi was so strong that Moinuddin decided overnight to distribute all his wealth and belongings among the poor and became a qalandar roaming around the streets. He travelled extensively to places like Bukhara and Samarkand as these were the centres of knowledge and mysticism. Finally, he met Usman-e-Harooni who initiated him into what later came to be known as the Chishtiya Order.

Moinuddin travelled further to Baghdad, Hamadan, Tabriz and Herat, imbibing the culture and practices of many shaykhs. Often, these practices were very harsh, involving meditation, breath control (habs-e dam), etc. Some of these practices were ultimately assimilated with the body control rituals followed by the rishis and sadhus in India. Moinuddin also met Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki in Oosh, a place near Fergana (in present-day Uzbekistan). They decided to travel to India to spread their message. Moinuddin Chishti first arrived in Lahore and paid his obeisance at the tomb of Ali al-Hujwiri, before moving on to Delhi, and then finally settling in Ajmer. Similarly, Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Ka’ki first went to Multan and finally settled in Delhi. Their disciples soon started spreading their messages to other parts of India. Baba Fariduddin Ganj-e Shakar, whose grave is in Pakpattan, Pakistan, was a disciple of Bakhtiyar Kaki, and his disciple in turn was Nizamuddin Auliya, followed in the lineage by Nasiruddin Chiragh Dehlavi. They are considered to be the five major saints of the Chishti silsila.

One of the primary aims of the Sufis was definitely the da’wa to the message of Islam, even though it may not be appropriate to see them as ‘missionaries’ since there was very little institutionalization in their efforts of proselytization, at least in the early days of South Asian Sufism. But the literature they wrote or composed is not necessarily all about Islam. The message of Islam, in any case, could not be spread in an alien land without preparing the grounds for its assimilation. The Sufis had to learn and use the local languages and idioms and even performative practices, such as incantations, dress codes etc., to communicate with the masses. In fact, through their use of local dialects in north India, the Sufis may have had a significant role in the development of modern Urdu-Hindi or Dakhani as the lingua franca. Many Sufi poets from 14th to 17th centuries such as Amir Khusrau in Delhi and Bandanawaz Gesudaraz in Deccan are credited to have composed poetry in the local dialects that are considered the earliest examples of Urdu, Hindvi or Dakhani.[5]

Since a large number of the people attracted to them were from the underprivileged class or members of the ‘lower castes’ of the Indian social order, the Sufis wrote against social oppression and other dogmatic traditions they found prevalent in the society. They spoke of love, egalitarianism, and justice in a society that was gripped by strict social hierarchy and dogmatism. Thus, the religious message of Islam found further relevance in the form of social reform and critique. These messages of the Sufis sometimes surpassed the scope of canonical Islam and even criticized or ridiculed its dogmas. Many Indian Sufis developed further insights on Islam’s philosophy and even developed newer theories and interpretations of the Quran and the hadith. Thus, South Asian Sufi literature of the last 800 years has to be seen in this socio-historical context.

All over South Asia, the Sufis became public heroes due to their acclaimed miraculous abilities to triumph over natural hazards, enemies and people’s misfortunes or emotional crises, and attracted thousands of devotees from near and far to their abodes. Even after death, their hospices (known as ‘khanqah’s) and tombs became centres of pilgrimages, often associated with special attributes or powers. Anecdotes about their miracles and other spiritual or moral achievements became part of the public narrative in the form of songs, texts and sometimes, popular images. A pilgrimage to these shrines was considered a special act of devotion for local Muslims, who often could not afford a pilgrimage to Mecca. They made offerings at the shrine, which were collected by sajjadah nashins (hereditary caretakers) as their fees for conducting a special prayer. The pilgrimage centres were also beneficial to the local traders, since the pilgrims purchased memorable gifts, including images or replicas of sacred objects, as mementos.[6]

It is also believed that Chishti shrines such as the one at Ajmer and Fatehpur Sikri became more popular centres of pilgrimage after the Mughal king Akbar patronised them as he was blessed with his long-awaited son Salim after special prayers at these shrines. Akbar got many permanent tombs or marble structures constructed in Ajmer and other Sufi centres. Although a ziyarat or pilgrimage to Ajmer could not substitute a Hajj to Mecca, its importance for many was no less–some even call it a chhota Hajj (minor pilgrimage). Even today, thousands of people from all over South Asia make a long journey via several other shrines to reach Ajmer during the urs (death anniversary) of Khwaja Moinuddin, popularly known as Gharib Nawaz (benefactor of the poor).

Amir Khusrau, the literary pioneer

The most famous voice of the Chishti order, Amir Khusrau Dehlavi, was born in 1253 AD of Turk-Indian parentage. Employed in the courts of as many as seven rulers of the Delhi Sultanate, he composed many volumes of Persian poetry and prose that contain some of the finest verse produced in South Asia, as well as a wealth of information for historians. Due to his famed association with Delhi’s Nizamuddin Aulia (d. 1325 AD) millions of ordinary people across South Asia admire him as a saint, a musician, and a folk poet–attributing a large repertoire of lively poetic expressions and musical inventions to him. In fact his Persian poetry also spread to, and is still read and sung in, the larger Persianate world, including Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Khusrau’s father, a Turk soldier, migrated from Transoxiana to settle in Delhi and married the daughter of an Indian officer. Khusrau received his education in a maktab (Muslim elementary school) and showed extraordinary talent in Persian poetry from an early age. After the death of his father, he was brought up by his maternal grandfather, whose position in the court helped Khusrau pursue a career in the court as well. His jobs ranged from being a soldier, chronicler, advisor, and poet whose ghazals (love poems) entertained the evenings at the court. Persian poetry in India had begun to develop its own characteristic idioms steeped in the Indian soil, and Khusrau was one of the first to have contributed to the emerging Indian school of Persian poetics called the Sabk-e Hindi. His mathnavis (long poems describing events) and ghazals are considered among the best in the Persianate world, comparable to the works of masters like Nizami, Sa’di, and Jami. Khusrau brought a new ghazal to the court of Jalaluddin Feroz Khalji every day and was rewarded handsomely[7]. The kings knew that his mathnavis would make them immortal, and they certainly did.

While travelling with the kings on military campaigns or other assignments, Khusrau kept returning to the hospice of Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia in Delhi, an important Sufi of the Chishtiya order that was established in Ajmer, Rajasthan, by Moinuddin Chishti. Nizamuddin had a large following among the masses of Delhi, something the contemporary kings were quite envious of. Khusrau, despite being a courtier, was Nizamuddin’s favourite companion and disciple. He not only composed and recited ghazals for his spiritual master, but also received the latter’s guidance in the refinement of his poetic skills, especially in his rendering of the passion of romance[8]. Contemporary accounts and Sufi hagiographies contain endless anecdotes about their affectionate relationship, which helped in the making of their combined legend that still attracts thousands of devotees to their twin mausoleum in Delhi, where professional qawwali singers still perform Khusrau’s poetry.

While Amir Khusrau may have been a link between the Sufi world and the royal court, most Sufis preferred to remain aloof from the ruling class. Nizamuddin Aulia especially never allowed any king to meet him—there are many anecdotes about how he avoided meeting the Khalji and Tughlaq kings, who were aware of the former’s popularity and spiritual prowess.

The kings nevertheless made efforts to pay their respects to the Sufi saints and take their blessings. An early 17th-century painting from an album shows Shaikh Moinuddin Chishti holding a small globe (topped by a crown of the Timurid dynasty) which he intends to give to Mughal emperor Jehangir, proclaiming that “the key to the conquest of the two worlds is entrusted to your hand.”[9] The facing folio in the same album shows Jehangir himself holding that globe. The Mughals considered Chishti Sufis as their spiritual guardians, and consolidated their shrines all over India. Many other Mughal miniatures show meetings or passing on of favours between the kings and saints, despite the fact that many Chishti Sufis wished to keep a distance from the rulers.

Through the teachings and sermons of many Sufis, their hospices or khanequahs became centres of learning and knowledge production. Nizamuddin Aulia’s life and teachings were constantly memorized and documented by his disciples in the form of malfuzat or hagiographies. The most important of these are Fuwaid-ul Fuad by Hasan Sijzi[10] and Siyar-ul Auliya by Amir Khurd Kirmani, which document the day to-day sayings and anecdotes with the saint. These were followed by many other hagiographies in Persian and later in Urdu. Even Amir Khusrau is attributed to have compiled a text called Afzal-ul Fawaid, although it has not been authenticated by historians.

Sufis in the Awadh region

One of the earliest-known Muslim saints in the region of Awadh (now Uttar Pradesh) is a warrior named Salar Masud Ghazi who came with the army of Mehmud of Ghazni at the age of 16, and was martyred in a battle with the local Hindu rulers in Behraich in 1032 CE. He is buried at Behraich and his shrine is now a centre of pilgrimage for thousands of Hindus and Muslims every year, especially due to its supposed healing powers. Since Ghazi died unmarried, an annual memorial at his shrine, just outside the Behraich town, is supposed to celebrate his post-mortem wedding with a person named Zohra Bibi.[11] Even today, many young unmarried women visit the shrine dressed like brides for his blessings. There are also popular music videos and audio cassettes available outside the shrine featuring devotional songs in praise of the warrior-saint.[12] However, it is not known as to which formal Sufi order Salar Masud belonged and what his mystic inclinations were.

In a cemetery in Ayodhya, one can find so many ancient tombs of Sufi saints and Muslim figures that it is called Khurd Mecca (‘small Mecca’).[13] Among the other early Sufis to have arrived in Awadh was a person known as Qazi Qidwat ud-Din, who came from Central Asia at the behest of Usman Haruni (the Sufi master of Moinuddin Chishti who settled in Ajmer).[14] Considered an ancestor of the famed Qidwais of Lucknow, Qazi Qidwat died in 1208 CE and was buried in the complex of the now-demolished Babri mosque. Many of these early Sufis were scholars of Islam, philosophy and mysticism, and some also practiced the sama, which literally means ‘listening’, and is a prayer ceremony that involves singing, playing instruments, recitation of poetry and so on, leading towards a mystical experience.

Some information about their lives can be gleaned from the hagiographical accounts, some of them mentioned in Razi Kamal’s survey of Awadh’s Sufis. Shaikh Badruddin Wa’iz, an orator par excellence from Ayodhya, lived in the period of Alauddin Khilji (reigned from 1296–1316 AD). His spirited sermon gatherings were attended by many, some of whom were said to faint as a result of ecstatic crying upon listening to him.[15] The early Sufis may not have strictly followed the doctrine of any one particular Sufi order such as Chishti, Qadiri, Suhrawardi, Qalandari, or Naqshbandi that came into India, although the Chishti silsila was definitely one of the more popular orders whose members were appointed by their shaikhs into small and large towns in the Awadh region.

Syed Ashraf Jahangir Semnani, buried in Kichhauchha, a small town near Lucknow, came from Semnan in Iran where he was born in 1308 AD in a ruling family. He was a Sufi of both the Chishti as well as Qadiri orders, and naturally listened to sama and qawwali. Before coming to the Awadh region he had already stayed for some years in Uchch (now in Pakistan, near Multan) and Bengal. It is said that when he sensed his end was near at the ripe age of 120 years, Ashraf Jahangir asked for a mehfil of sama to be arranged, and died trembling like an injured bird (murgh-e bismil) while listening to a particular verse of the poet Sa’di.[16] Even today, his shrine receives thousands of devotees for its supposed healing powers, especially during his urs when qawwalis are performed.[17]

Many disciples of the Chishti saint Nizamuddin Aulia of Delhi (or others in his lineage) were appointed the spiritual heirs in Awadh, Qazi Mohiuddin Kashani being one of the most important ones. He left his courtly job as a qazi (judge) in Awadh during Alauddin Khilji’s rein to follow the mystic path taught by Nizamuddin Aulia–often disappearing into forests with his book of prayers to meditate. Similarly, Nasiruddin Chiragh Dehlavi, the most famous disciple of Nizamuddin Aulia, was born in Ayodhya around 1274 AD, and his descendents to this day have connections with Awadh. There are many others such as Shaikh Shamsuddin Awadhi, Jalaluddin Awadhi, Jamaluddin Awadhi, Qiwamuddin Awadhi, and Kamaluddin, who were either direct or hereditary disciples of Nizamuddin Aulia, and practiced the listening of sama and qawwali in their spiritual experiences.[18]

Maulana Alauddin Neli (d. 1360 CE) was another disciple of Nizamuddin Aulia based in

Awadh, who was popular for giving powerful wa’z or sermons about mysticism. His Friday sermons were even attended by the famous Arab traveller Ibn Batuta (1304-1377) who describes the ecstasy experienced by his listeners. During one of Neli’s sermons, when a particular ayat (passage) of the Quran was recited, a restless listener in the mosque reacted with a loud scream. When the passage was repeated during the session, the person screamed with ecstasy again and ultimately died on the spot. Ibn Batuta claims to have attended his funeral too.[19]

One can find many other accounts of the early Sufis of Awadh in which their deep interest in poetry and music is apparent. For instance, Syed Ali of Jaunpur (1423–1500) was never particular about any specific song or style of music for sama, ‘I can get wajd (ecstasy) with any ghazal or verse being recited’, he would say.[20] Similarly, Shaikh Adhan Jaunpuri (born 1452) lived for over 100 years and used to get so mesmerized by listening to qawwali that he had to be controlled by over 10 people even in his old age.[21] Shaikh Adhan may have also been an important person for the Mughal ruler Babur in Delhi since he is said to have organised mehfils of sama in the latter’s court, along with another courtier, Shaikh Dhoran. Moreover, Adhan’s disciple, Shaikh Banjhu, a ‘very sweet singer’ from Jaunpur, got employed with King Akbar and was rewarded suitably for his music performances.[22]

Lucknow’s most prominent Sufi shrine today (near the present Medical College) is that of Hazrat Shah Mina Chishti (d. 1479) who was the son of another Sufi, Shaikh Qiwamuddin and a disciple of Shaikh Sarang. Being initiated into not only the Chishtiya but also the Qadiria, Suhrwardiya and Qalandaria orders, Shah Mina is also attributed with many miracles which he is supposed to have performed since his childhood.[23] Among other Sufis of this region, Alauddin Husaini Awadhi (d. 1560 AD) was not only a Persian poet par excellence but also an expert in Hindustani music. He is buried in the Khurd Mecca cemetery of Ayodhya.

Many other Sufi shrines of Awadh from the medieval period have remained centres that promote qawwali during the urs ceremonies. Among the unique institutions of Lucknow that supported Sufi ideology and qawwali, albeit indirectly, is one known as Firangi Mahal. Although Firangi Mahal (literally meaning a ‘foreigner’s palace’, once inhabited by a European trader in the 17th century) refers to one of the earliest Muslim families, which migrated to Awadh from Afghanistan, it is more popular as a madrasa or educational institution established by this family of great scholars centuries ago.[24]

Mullah Nizamuddin, a prominent member of this family from the 17th century compiled an elaborate syllabus for the study of Arabic and Persian that is still taught in some madrasas of India, and is known as the Dars-e Nizami (Nizam’s syllabus). Besides being authors of hundreds of books (and exegeses of older works) on philosophy, jurisprudence, religion, literature and mysticism, the members of the Firangi Mahal family were also Sufis themselves.[25] Many family members not only composed mystical poetry but also listened to Sufi sama and qawwali. According to Maulana Azad, several members of Firangi Mahal were well-versed in music.[26]

While many Sufi saints lived and practiced their mysticism in the Awadh region throughout the last millennium, very few may have matched the popularity of Haji Waris Ali Shah of the 19th century. Waris Ali was born in the Dewa town of Barabanki district (near Lucknow) around 1809 and travelled extensively, all over the country as well as to other parts of the world, especially on his pilgrimages to Mecca, as a barefoot fakir wearing an ihram (two unstitched pieces of white cloth worn by Hajj pilgrims) throughout his life. Waris Ali was fond of listening to poetry and sama, and one of his most favourite disciples was Avghat Shah Warsi, a poet from Bachhraon (near Moradabad) who composed mystic poetry, especially dohas (couplets) in Awadhi, Braj and Urdu languages, for his Sufi master.[27] Some of Avghat Shah’s poetry is still sung by qawwals, such as Meraj Nizami of Delhi who featured at least one such verse in his collection—a song in Braj in praise of the Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon Him).[28]

Sufis at the shrine of Haji Waris Ali still follow the tradition of wearing a light yellow-coloured ihram or unstitched cloth while attending ceremonies like qawwali mehfils. Most followers of Haji Waris, including qawwals, use Warsi as their title, and have spread outside the Awadh region too—as far as Hyderabad (Andhra Pradesh), Karachi (Pakistan) and even some western countries. A well-known follower of the saint was the poet Bedam Shah Warsi (d. 1936) whose poetry is regularly performed by qawwals in India and Pakistan. At least seven of Bedam Shah’s poems are documented by Meraj Ahmed Qawwal for the purpose of qawwali performance.[29] Aarzoo Lakhnavi (b. 1882) was also a poet whose devotional verses are part of the qawwals’ repertoire.

Several rural areas on the outskirts of Lucknow nurtured literature and performative traditions related to devotional Islam and Sufism that carry strong bonds of pluralism. One of them is Kakori, a small historic town outside Lucknow that has been famous for the scholars, poets and Sufis it produced. One of its poets, Mohsin Kakorvi (d. 1905), not only wrote na’tiya qaseedas (long poems in praise of the Prophet Mohammad), but also syncretic Urdu songs like Simt-e Kashi se chala janib-e-Mathura badal (A cloud from Kashi sailed towards Mathura…) that is full of devotion for Lord Krishna. Kakori is also famous for the Sufi poets Shah Muhammad Kazim Qalandar and Shah Turab Ali Qalandar whose poetry is full of mystic philosophy bearing Indian symbols of bhakti and references to Lord Krishna.[30] Similarly, poet Hasrat Mohani, born in 1875 at Unnao near Lucknow, was a great admirer of Krishna and wrote several Urdu verses celebrating the romantic lore of Krishna and Radha as Sufi symbols of love.

This is a select and brief account of some Sufis and their silsilas in north India in the past millennium. It does not feature many Sufis and their literary activities in the southern and eastern parts of India. Some other articles and features in this evolving module would focus on the other regions and individuals as well.

[1] Ernst, Carl W. ‘Two versions of a Persian text on yoga and cosmology attributed to Shaykh Muín al-Din Chishti’, Elixir no.2, 2006: 69-76,124-125.

[2] Ernst, Carl W., ‘Sufism and Yoga according to Muhammad Ghawth’, Sufi 29, spring 1996: 9-13.

[3] Zarcone, Thierry, ‘Central Asian Influence on the Early Development of the Chishtiyya Sufi Order in India,’ in Muzaffar Alam et al (ed.), The Making of Indo-Persian Culture, Delhi: Manohar, 2000, pp. 99-116.

[4] Zarcone, Thierry, ‘Central Asian Influence on the Early Development of the Chishtiyya Sufi Order in India,’ in Muzaffar Alam et al (ed.), The Making of Indo-Persian Culture, Delhi, 2000, 99-116.

[5] Abdulhaq, Maulvi, Urdu ki Ibtedayi Nash-vo-numa mein Sufia-e Karam ka Kām, Delhi: Anjuman Taraqqi-e Urdu Hind, 1995.

[6] Saeed, Yousuf, Muslim Devotional Art in India, New Delhi: Routledge, 2012.

[7] Barani, Ziauddin, Tarikhe Firoz Shahi, partial translation in Rasheed Malik, Barre-sagheer mein Mauseeqi ke Farsi Ma’akhaz, Lahore, 1983, p 487

[8] Ahmed, Shaikh Saleem, ed., Amir Khusrau, Delhi, Idara-e Adabiyat-e Dehli, 1976.

[9] The two paintings (by Bichitr, circa 1620) are from an album belonging to the Earl of Minto, in the collection Muraqqa': Imperial Mughal albums from the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, UK.

[10] Lawrence, Bruce B. (Editor, Translator), Morals for the Heart: Conversations of Shaykh Nizam Ad-Din Awliya Recorded by Amir Hasan Sijzi, (Classics of Western Spirituality), 1991.

[11] Schwerin, Kerrin G.V., ‘Saint Worship in Indian Islam: the Legend of the Martyr Salar Masud Ghazi,’ in Imtiaz Ahmad, ed., Ritual and Religion among Muslims in India. Delhi: Manohar, 1981, pp. 143-161.

[12] See for instance a video CD titled Ghazi ka Karam (Blessings of the Warrior-Saint), artists: Neha

Mehmood Khan, Asif Saidpur, produced by Golden Eye Films, no date. (Purchased in 2008).

[13] Rajalakshmi, T. K., ‘Ayodhya, a picture of diversity,’ Frontline, Volume 20 - Issue 22, October 25 – November, 07, 2003 (An article on two documentaries about the Sufi shrines of Ayodhya, produced by Vidya Bhushan Rawat).

[14] Kamal, Razi Ahmed, Mukhtasar Tarikh Mashai’kh-e Awadh, Delhi: Alhasanat Books, 2006, p. 30.

[15] Ibid. Razi Kamal, p. 33.

[16] Samnani, Makhdum Ashraf, Lataif-e Ashrafi, vol. 2, pp. 406-412. Quoted by Razi Ahmed Kamal.

[17] Ashrafi, Syed Ali, ‘Athwin sadi hijri ke sahib-e karamat buzurg: Syed Ashraf Jahangir Samnani,’

Naya Daur, Oct-Nov.1994, Awadh number part 2, Lucknow: DIPR, pp. 132-135.

[18] Ibid. Razi Kamal, pp. 41-55.

[19] Hasani, Abdulhayi, Nuzhatul Khawatir (vol. 2), quoted by Razi Ahmed Kamal, 2006, pp. 61-62.

[20] Dehlvi, Abdulhaq Muhaddis, Akhbar al-Akhyar (translated from Persian into Urdu by Subhan

Mehmud, Mohd. Fazil, and Moinuddin Na’imi), Delhi: Farid Book Depot (no date), p. 481.

[21] Ibid. p. 481.

[22] Brahaspati, Kailash Chandra, Muslman aur Bhartiya Sangeet, Delhi, Rajkamal, 1974. (Quoting Athar Abbas Rizvi and Abdul Qadir Badayuni).

[23] Ernst, Carl W. and Lawrence, Bruce B., Sufi martyrs of love: the Chishti Order in South Asia and

beyond, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, pp. 54-57.

[24] Robinson, Francis, ‘The ulama of the firangi mahal and their adab’ in B. Metcalf, ed., Moral

Conduct and Authority in South Asia, Berkeley, 1984.

[25] Ansari, M.Waliul Haq, ‘Firangi mahal ki ilmi, adabi, aur siyasi khidmat’ (in Urdu), Naya Daur, Feb-March 1994, Awadh number, Lucknow: DIPR, pp 40-52.

[26] Azad, Abul Kalam, Ghubar-e Khatir (Urdu), edited by Malik Ram, Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1967.

[27] Warsi, Anis Ahmed (compiled), Avghat Shah Warsi’s Faizan-e Warsi (Also known as Zamzama-e

Qawwali), Delhi: S.A. Publications, 2006.

[28] Qawwal, Meraj Ahmed, Surood-e Ruhani, Qawwali ke Rang, Delhi, 1998, p. 342.

[29] Ibid. Meraj Ahmed (see table of contents for the mention of Bedam Shah’s poems).

[30] Tariq, Shamim, Sufia ki She’ri Basirat mein Shri Krishn, Delhi: Educational Publishing House, 2009.