Sufi Images from Pakistan Depicting Lal Shahbaz Qalandar

1 Introduction

Since the early 20th century, coloured images and posters visualising Islamic belief and piety were printed and marketed as religious commodities in cities such as Cairo, Damascus, Tehran, Lahore, Bombay, Delhi and Madras. In addition to calligraphic verses from the Qur’an, views of the holy places of Mecca and Medina, the Prophet Muhammad’s celestial mount Buraq, members of the Holy family (ahl al-bait), Shi’ite Imams and martyrs of Karbala, heroes of Islam as well as narrative figural scenes with Qur’anic themes, a sizeable number of prints from Muslim South Asia shows Islamic mystics.

Particularly in Pakistan, a heartland of the Sufi tradition and related shrine Islam, poster-portraits depicting saints and their mausoleums are powerful devotional aids containing symbols of vernacular religious practice. Thus, the general Islamic avoidance of figural representations is disregarded at this popular level where posters serve as a vivid medium of piety in the realm of everyday religiosity. Displayed (and at times garlanded) privately at home or publicly in shops, restaurants, haircutting salons, offices and shrines, they create a sacred Islamic space making Sufism explicit. They bear testimony to the popular reverence for and perception of the ‘friends of God’ (awliya), unfolding a world of devotional imagination.

Produced since the early twentieth century by bazaar painters, illustrators and collage-artists, Sufi images reflect the visual aesthetics of Muslim popular religious art steeped in exuberance and playfulness. Such Islamic prints should not, from a purely Western perspective, dismissively labelled and condemned as ‘kitsch’. Rather, in popular religious practice in Pakistan, portraits of saints are rather sacred objects with their own metaphorical language which become the focus of authentic lived experience. These dense and crowded posters reveal a rich iconography of charismatic sainthood: In addition to many imaginary depictions, there are photographs and a few authentic painted portraits, miracle stories are illustrated and we observe a multitude of symbolic elements conveying specific religious values of piety.

In Pakistan, Sufi posters are mass-produced consumer items of the bazaar industry, predominantly printed and distributed from Lahore to the low-lands of the Punjab and Sindh. Pilgrims purchase them as souvenirs during saints’ festivals. At home they are framed and finally serve as media of veneration. They are icons of love and devotion bestowing saintly blessings, protecting from the evil and so-to-speak bringing the saints into the home. In this context, they also express the devotee’s personal religious identity. More than any other holy man who found his last resting place in what is now Pakistan, the saint Lal Shahbaz Qalandar is represented within this genre of Sufi poster art on a particularly large number of colour prints.

2 Lal Shahbaz Qalandar

Within the popular Sufi tradition of Pakistan, Shaikh Usman Marwandi (d.1274 CE), better known by his honorific title Lal Shahbaz Qalandar – ‘red royal falcon’, is the most celebrated saint with the largest following. He is also venerated as a divine hero by Hindus living in the southern province of Sindh. But the great Qalandar is above all the pivotal figure of the mystical Qalandariyya, an antinomian movement of peripatetic dervishes originating in the early thirteenth century in the area of Syria, Anatolia, Iran and Central Asia in the course of the Mongol invasion. Born near Tabriz in Azerbaijan, he wandered eastwards through Iran and Makran to reach the Indus valley where he finally settled in the small town of Sehwan in Central Sindh. Enraptured by his ardent love to God, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar became a charismatic Sufi saint characterized – according to historical accounts – by severe asceticism as well as by venerating the Beloved through intoxication and trance-like dance.

The image of Hazrat Sakhi Shahbaz Qalandar (‘The lord, the bounteous, Shahbaz Qalandar’, as he is often respectfully named) not only appears as a familiar visual sign on poster-prints, but also on a large number of other devotional objects, such as stickers, small pocket-size laminated pictures, postcards and plastic pendants. His imaginary portraits are also printed on the covers of video and music cassettes featuring musical styles such as qawwalı, ka fıañ and Qalandrı dhammaliañ. Thus, his icon is almost ubiquitous in the visual culture of Pakistani Sufism. The present paper aims to look at the iconographical diversity of Qalandar posters and its symbolism as a means to understand the immense popularity of the saint’s cult.

Within Pakistani Sufi poster art paintings and collages depicting Lal Shahbaz Qalandar show a remarkable variety: in our collection at the Museum of Ethnology in Munich we have 23 posters (referred to in the footnotes with their inventory numbers), five ‘ıd greeting cards (published by Saqib Card Centre in Saddar, Karachi) and two du‘aya cards which are the source of the following notes on their visual language.

3 The Iconography of Qalandar Posters

3.1 The Qalandar and his Shrine

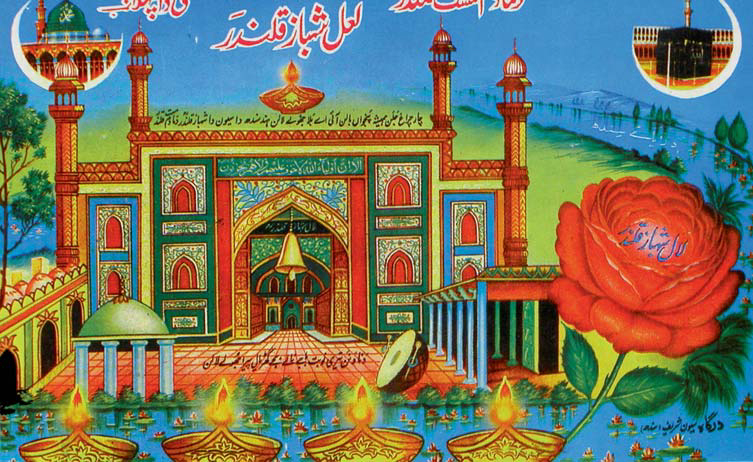

A poster acquired in the late 1980s shows a painted view of the dargah and rawzah mubarak with its then splendid tile façade, four minarets and two red flags on the roof. The colonnaded hall and the domed pavilion depicted in the foreground have been removed in the course of extensive ‹renovation› at the end of the twentieth century. A similar view of the shrine is found on a small ‘ıd greeting card – a charming piece of popular religious art – showing the monument at the river Indus (fig. 1). The context of devotional practice is indicated by four lighted oil-lamps placed in the foreground and a fifth one hovering over the top of the shrine. These lamps are icons of devotion referring to the offering of light. The verse written above the shrine says that, in addition to the four everburning lamps, the devotee will burn the fifth for the saint – the total number five being auspicious particularly for Shias. A further detail of this picture is the large drum placed in the courtyard of the shrine referring to ecstatic Sufi music as well as the red rose on the right side inscribed with the Qalandar’s name.

Fig. 1:‘ıd greeting card depicting the shrine in Sehwan Sharif. © Private collection.

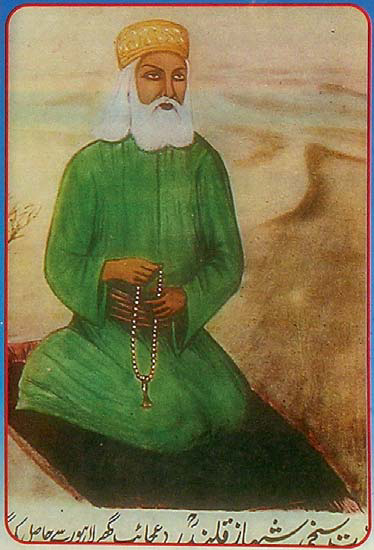

Apart from these two prints, all those discussed below have figural representations on them. Often (but not always) the Qalandar is depicted in a seated pose in the right corner, that is to say, in the proper place of pre-eminence and high status. In fact, comparable to Arabic writing, many Islamic posters should be read from right to left. This is the case not only with the previous ‘ıd card where the rose symbolises the saint, but also with posters showing either a miniature-like image of the white-bearded and green-clad Qalandar (fig. 2) based on a nineteenth or early twentieth century painting allegedly kept in the Lahore Museum or – more often – an image of the saint in his middle age with dark hair, only slightly turned grey, dressed in a saffron-coloured robe – the colour of the Qalandar’s dress according to historical sources – and wearing a green shawl. The later image is a standard depiction showing the saint either sitting in the characteristic Sufi kneeling position counting prayer beads or cross-legged with his hands raised in prayer. Both variations are originally composite ones, the head borrowed from a Christian devotional painting and put on a so-to-speak ‘Sufi-cated’ torso. Sometimes the head has also been painted and thus copied from the original Christian model as shown in several posters. Most personality posters depicting the saint give a full view of the shrine building often accompanied by a more detailed view of the richly adorned tomb (fig. 3).

Fig. 2: Idealised image of the Qalandar based on a painting allegedly kept in the Lahore Museum, detail of a contemporary poster. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

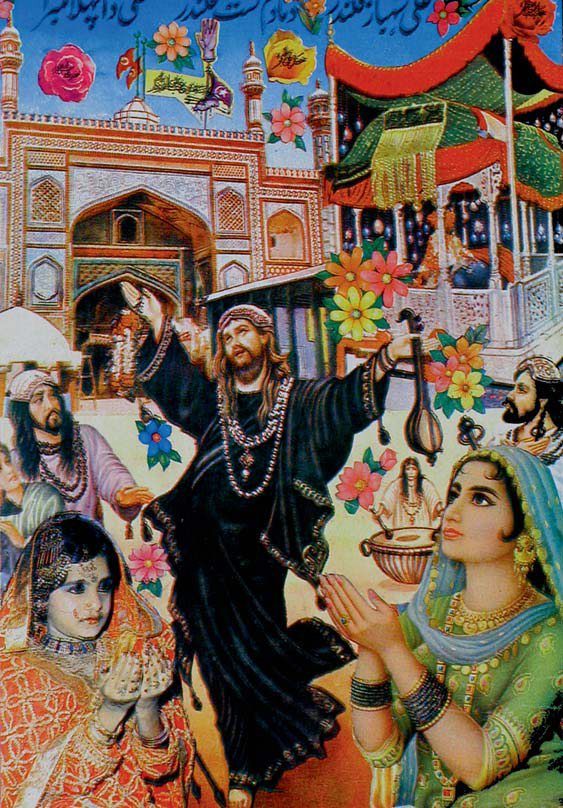

Fig. 3: ‘ıd greeting card depicting the saint’s tomb, his mausoleum and the dancing Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. © Private collection.

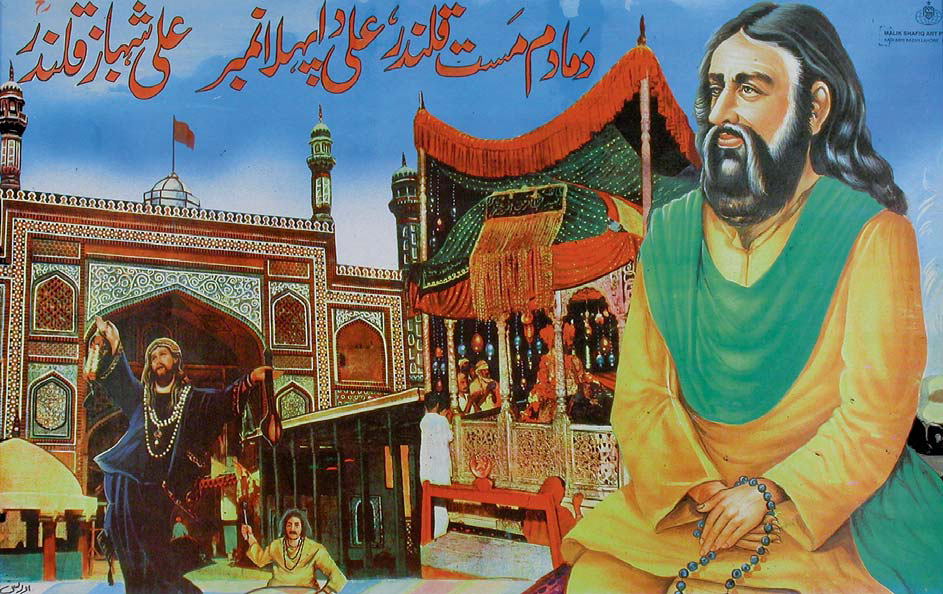

Fig. 4: The Qalandar in contemplation and in the movement of dancing, poster. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

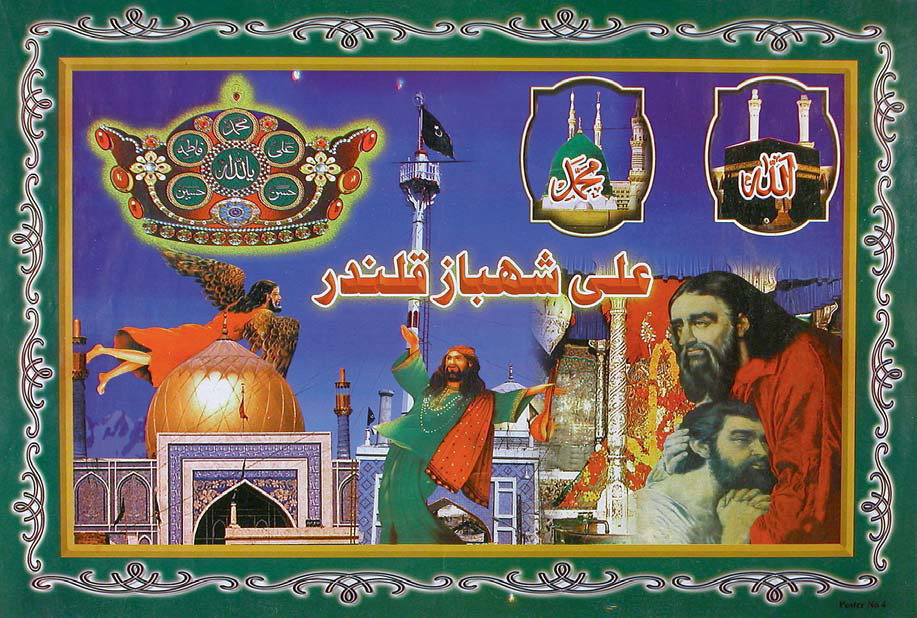

Figure 4 shows a very common composition which combines painted depictions stemming from poster art between the 1960s and 1980s with photography. The Qalandar’s shrine topped by a red flag is seen in the background, a photographic view of the tomb with devotees is placed in the middle ground, leaving the foreground for figural representations of the Qalandar, in prominent seated position as well as smaller in size moving in dance. Two posters from the latest period of poster art (ca. 1990s to 2000s) show the Qalandar’s golden domed mausoleum after renovation with the huge red-flagged pole (‘alam) next to it. The second one has the saint’s tomb with its elaborate silver enclosure and the famous heart shaped stone known as sang-e maftul on the right side and iconic views of the Kaaba and the Prophet’s tomb on top of it. The sang-e maftul is a sign of the saint’s humility and asceticism.

3.2 The Flying Saint

According to hagiography, the Qalandar once transformed himself into a falcon to travel to Mecca. On another occasion he went by air to Multan to save his friend Shaikh Sadr ud-Din Arif, the son of the famous Suhrawardi saint Baha ud-Din Zakariya (1171–1262 CE), from the hands of a pagan ruler – hence his honorific laqab (epithet) Shahbaz (‘royal falcon’). Because the colour of his robe is said to have been la’l (‘red like a ruby’), he is called the ‘red royal falcon’ out of devotion. In a mystical sense imagined as flying high in the spiritual domain, the pious mind of devotees turns him into a miracle-working saint with superhuman powers who is imagined to metamorphose into a man with the wings of a falcon as depicted in popular visual Sufi art. In fact, his ability to fly marks the most important miracle of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar.

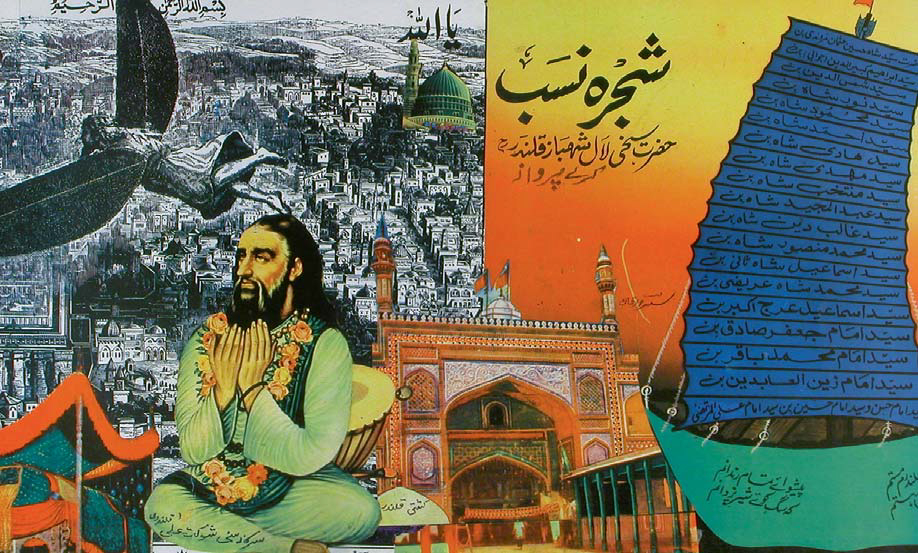

Fig. 5: The saint praying and flying in combination with religious epigraphy, poster-collage. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

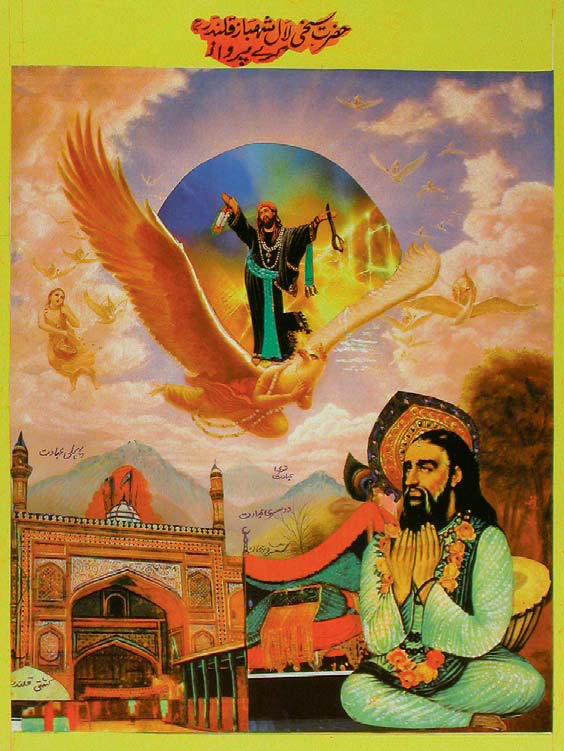

A collage with the saint’s genealogy written on the sail of a boat, a view of the shrine, the Qalandar sitting in prayer and a photograph of his tomb with canopy has a fascinating engraving as a backdrop (fig. 5). It gives a view of the medieval fortified city of Jerusalem from an elevated viewpoint with the rectangular temple mountain standing out. A bearded figure, clad in a knee-length tunic and spreading out large, leaf-shaped wings, flies high in the air. This Icarus illustration, borrowed from some book, is supposed to represent Shahbaz Qalandar flying towards Mecca for hajj. Another poster shows a modified, more focused version of this scene with theoriginal engraving of Jerusalem coloured in red, green and yellow and the figure of the flying saint wearing a red robe and equipped with the wings of a falcon.16 The first part of the inscription emphasizes this depiction and reads Hazrat Shahbaz Qalandar chalne ko ghora urne ko baz which means that the saint can run fast like a horse and can fly like a falcon. This depiction of the flying saint recently became an almost heraldic motif, often appearing smaller in size and sometimes in pairs on Qalandar posters as well as in hagiographic movies. A phantastic composition is shown on a print with the devotional icons of the saint’s figure sitting in prayer, his tomb and his shrine in the foreground giving ample view of the sky where Garuda – Vishnu’s holy mount – carries the Qalandar who is depicted in standing posture (fig. 6).17 The king of the birds and demigod of Hindu

mythology is wearing a crown and a long garland. In this scenery, borrowed from a Hindu poster, he is accompanied by a female musician (gandharvı).

Fig. 6: Lal Shahbaz Qalandar carried by the king of the birds, poster-collage. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

3.3 The Dancing Qalandar

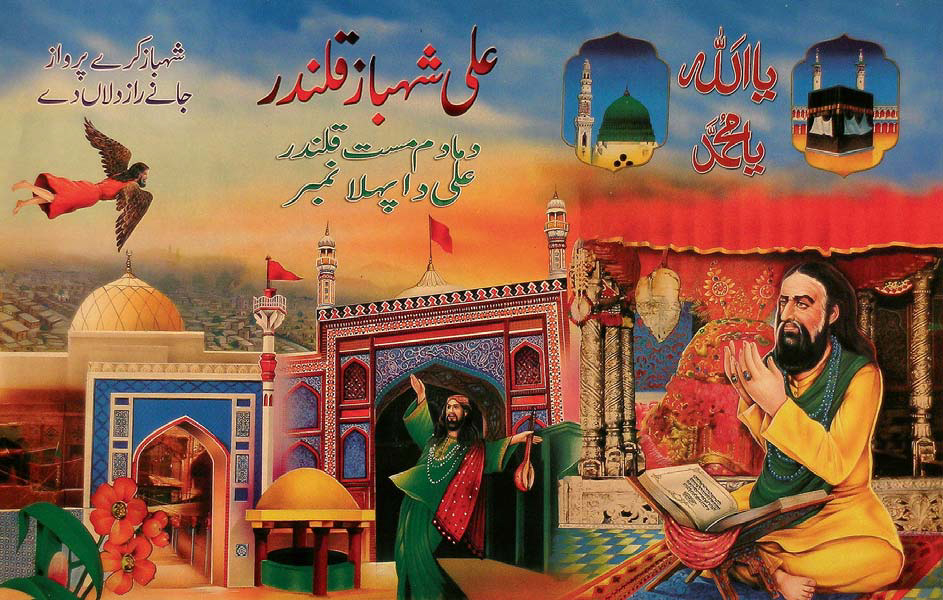

It is a peculiarity of Qalandar images not found on any other Pakistani Sufi posters that the saint is represented in a single picture by two or even three different figures whereby motifs are fused. Thus, collages from the 1980s show the saint in prayer on the right side and dancing on the left, usually with views of the shrine as a backdrop. Figure 7 is a triptych from the early 21st century which opens a wider space of view, in fact a ‘darshanic’ field (derived from the Sanskrit term dars´an – ‘auspicious sight’), denoting the all-pervasive gaze and presence of the Sufi saint. In the South Asian religious context (notwithstanding labels such as ‘Muslim’ or ‘Hindu’) dars´an means to be in the presence of the divine, receiving blessings through visual contemplation, but also through touching, adorning and verbally addressing the living or figurally represented saint or deity.

Unlike other Sufi posters allowing eye-to-eye contact between devotee and saint, it is here the Qalandar’s ‘gift of appearance’ made in different poses, especially in the movement of dance, which confers his blessing and leads to a ‘merging of consciousness according to devotionalist interpretation’.

Fig. 7: Triptych with figural representations of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, poster-collage. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

Already in several posters discussed above, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar is represented by an enraptured, bare-footed dancing figure in black robe taken from a Christian devotional painting showing Jesus and his apostles (see fig. 3). But, to identify this long-haired, bearded figure in a flowing garment with an original image of Jesus is problematic insofar as Christ is always depicted in standing position, sober, asexual and never in a movement of abandonment like here. Nevertheless, the posture of head, arms, hands and feet indicate that probably a figure of Jesus Christ on the cross could have been used, retouched, and the partly covered body finally dressed with a black garment. The figure has been further so-to-speak ‘Sufi-cated’ or – even more appropriately ‘Qalandar-ised’ – by placing a small lute and a flower garland in his raised hands and a Sindhi cap on his head. Likewise his disciples are equipped with chimtas (the fire-tongs and rhythm instruments used by Qalandars and Malangs), necklaces, bracelets and embroidered caps. In the background there is usually the image of a dervish beating a huge naqqara drum (typical for the ritual veneration in Sehwan); on a postcard he is substituted by a chimta-playing Malang wearing iron chains.

This emblematic image of the dancing Qalandar in frontal, heraldic representation – single or surrounded by his companions – is the focus of compositions in vertical and horizontal format. An ‘ıd greeting card in vertical format conveys the impression of horror vacui through filling space with additional images of female devotees, flowers and an ‘alam (Fig. 3). In comparison, the horizontal format leaves more space for the courtyard strewn with glass beads creating an aura of sacredness for the performance of dhammal, the ecstatic dance typical for ritual devotion at the shrine. A derivative image of the original Jesus-type representation of the dancing Qalandar shows the saint now dressed in green with a red shawl in a swaying movement more bent backwards. These pictures of the enraptured Qalandar performing dhammal seem to animate the devotee to go into trance dance himself, thus mirroring the action of the saint. In Alfred Gell’s words: ‘… the situation is defined in terms of the devotee’s own agency and result; the devotee looks and sees. The image-as mirror is doing what the devotee is doing, therefore, the image also looks and sees.’ (1998, 120)

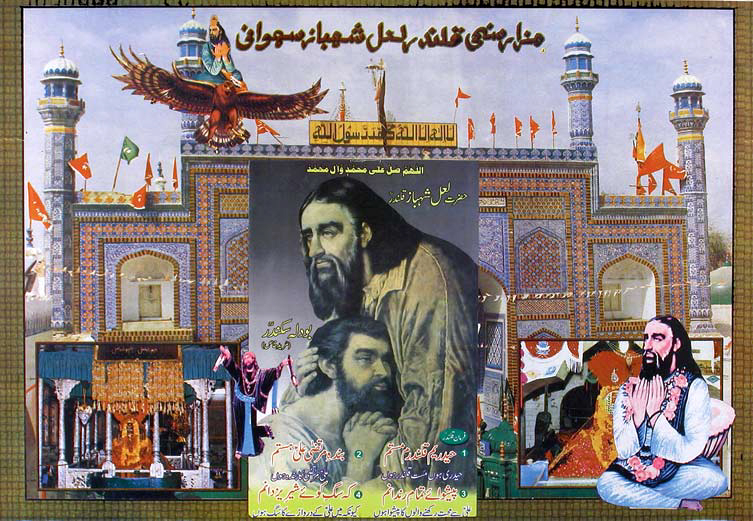

Fig. 8: Variety of figural representations of the saint with the Qalandar and his disciple Bodla in the centre, postercollage. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

3.4 Lal Shahbaz Qalandar and his Disciple Bodla Bahar

The image of the Qalandar together with his closest follower Bodla Bahar (in Sindhi Bodlo Bahar) recently has become another popular icon of love and devotion among pilgrims to Sehwan Sharif. The disciple’s Sindhi name roughly means ‘innocent spring’; on posters he is also called Bodla Sikandar. According to hagiography, Bodla Bahar lived in Sehwan already before the arrival of the Qalandar, cleaning the roads with his long beard.

He became his disciple and most loyal servant. One day the Qalandar ordered him to buy meat in the bazaar. Although Bodla had no money and things to barter for meat, he went to see the butcher Anud and commanded that his body be slaughtered and the pieces sold in the market. From the proceeds Anud should send good lamb to the saint. When Bodla did not return in time, his master went looking for him calling ‘Bodla! Bodla!’ Learning that his disciple just had been butchered, he became extremely distressed, collected the pieces of Bodla’s body and restored him to life. Such pious tales of obedience and deep affection as well as the shamanistic miracle of reassembling the dead body and bringing it back to life are the background for the iconic representation of both ascetics.

The portrait scene with the murıd-e khas (‘special devotee’) leaning his head against the heart of his master, hands folded in prayer and the Qalandar gently touching Bodla’s head with his right hand, seems to have been taken from a Christian devotional painting. The bearded figure imagined to represent Bodla Bahar looks as if originally been an apostle, probably Saint Peter who is consoled by Christ. Thus, this image also elucidates the Qalandar’s often shown middle-aged portrait in three-quarter profile which was mentioned above. The model image used in all the respective Qalandar posters appears to have been cut out from a Catholic devotional painting. It is best visible on two cards making a plea for prayer (du‘a). Such du‘ayya cards earning religious merit (sawab) were distributed during the annual festival at Sehwan in 2004. The one in vertical format has also been transposed to the centre of a charming collage bringing together almost all the figural representations of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar (fig. 8). On collage-posters designed and printed in recent years by a company called ‘Data Foto Frame Maker Dealer’, the holy couple is always placed in the lower right corner (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9: The Qalandar depicted flying and dancing and together with his disciple Bodla Bahar, poster-collage. © Museum of Ethnology, Munich.

3.5 The Qalandar in the Company of Other Saints

In Sufi poster art there is a particular type of composition showing imaginary assemblies of Muslim saints, sometimes depicting up to 60 holy men all grouped around ‘Abdul Qadir Jilani, the saint with the highest spiritual authority. The only saint in this ‘timeless conclave’ who is represented by two figures is Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. He is depicted side by side in two postures sitting in prayer and dancing in rapture. Furthermore, in compositions portraying three saints from Sindh, the Qalandar is seated in the right corner counting prayer beads. Together with Shah ‘Abdul Latif Bhitai he is the most famous mystic hailing from this province.

3.6 Epigraphy

In addition to saintly personages, monuments, iconographic references to Mecca and Medina, motifs with symbolic significance (such as rose, pigeon, candle, oil-lamp and crown) and the use of bright colours, calligraphy is an important complementary dimension to the visual message of these Qalandar posters. Calligraphic names and verses are both visually attractive and meaningful in content. Apart from standard Islamic formulas, such as the bismillah and kalima, invocations of Allah, Muhammad and ‘Ali, and the names of the panjtan pa k (fig. 9), we find honorific titles of the Qalandar and captions explaining depictions. But what is even more revealing for the veneration of the saint are specific devotional verses and formulas (bol). A popular reference to his enraptured state is dama dam mast Qalandar – ‘Alı da pehla numbar – ‘Alı Shahbaz Qalandar (fig. 3, 4, 7). The meaning of this bol is ‘through your breath, oh Qalandar intoxicated (by the divine) – ‘Ali is the number one – oh ‘Ali, oh Shahbaz Qalandar’. Sometimes only a part of this formula is printed on a poster. The picture with the shijrah-e nasab has, in addition, a well-known Persian couplet written on the boat which starts with the words haidariam qalandaram mastam (fig. 5, 8). This verse is also found on the advertising cards accompanied by an Urdu translation. Typical is the invocation of the Qalandar by the call jıve la’l – jhu le la’l – la’l badshah – ‘Long live Lal – oh thou of the cradle – king Lal’. This formula is frequently on the lips of pilgrims and also embroidered on votive hangings. Finally, there is also a poster with the inscription of the famous Urdu couplet tamanna dard-e dil kı ho to kar khidmat faqıroñ kı – nahıñ milta yeh gawhar badsha hoñ ke khazınoñ meñ: ‘If you want to feel the grief of the heart then you should serve the fakirs in a humble way, you do not find such a jewel in the treasure house of the kings!’

4 Conclusion

Within popular imagistic Pakistani shrine Islam the above-described and analysed posters depicting the miracle-working Lal Shahbaz Qalandar are colourful examples of local religious aesthetics targeting a mass audience. They are memorial images focusing on the extraordinary personality of the saint and his hagiography, but also evoking memories of the devotee’s own pilgrimage to Sehwan, and at the same time visually powerful icons of love and devotion cherished by his followers.36 All three figural representations of the Qalandar, namely the saint seated in prayer and contemplation, flying in the air and dancing in abandonment, express specific qualities attributed to him. As they are often found in public and private spaces in Sindh and the Punjab and even in hagiographic movies sold in Sehwan Sharif, Hyderabad and Lahore, they have become iconic in character. Through their bodily expressions these imaginary portraits are widely recognized and accepted as representing the historical saint who died in the 13th century. That means that the painter and collage-artist did successfully correspond to the common viewer’s visual literacy. Epigraphy supports the visual vocabulary of these devotional images of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar expressing piety, praise, love and hope to receive divine blessings.

Bibliography

Boivin, Michael (2003), Reflections on La’l Shahbaz Qalandar and the Management of his Spiritual Authority in Sehwan Sharif, in: Pakistan Historical Society 61/4, 41–72.

Boivin, Michel (2005), Le pèlerinage de Sehwan Sharif, Sindh (Pakistan): territories, protagonists et rituels, in: Chiffoleau, Sylvia/Madoeuf, Anna, ed., Les pèlerinages dans le monde musulman, Damascus, 311–345.

Boivin, Michel (2006), Devotion and Iconography: The Figures of Popular Piety in the Indus Valley, in: Nukta Art 1/2, 46–52.

Centlivres, Pierre/Centlivres-Demont, Micheline (1997), Imageries populaires en Islam, Geneva.

Flaskerud, Ingvild (2008), Visualising Belief and Piety. Representation, Reception, and Function of Imagery in Iranian Shiism, PhD dissertation, University of Bergen.

Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim (1998), Saints in Modern Devotional Poster-Portraits. Meanings and Uses of Popular Religious Folk Art in Pakistan, in: Res. Anthropology and Aesthetics 34, 184–191.

Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim (2003/2004), Devotional Service at Sufi Shrines. A Punjabi Chara gwa la and his Votive Offering of Light, in: Journal of the History of Sufism 4, 255–262.

Frembgen, JürgenWasim (2006), The Friends of God – Sufi Saints in Islam. Popular Poster Art from Pakistan, Karachi.

Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim (2007), Sufi Poster Art, in: Journal of the History of Sufism 5, 329–335.

Frembgen, JürgenWasim (2008), Journey to God. Sufis and Dervishes in Islam, Karachi.

Gell, Alfred (1998), Art and Agency. An Anthropological Theory, Oxford.

Puin, Elisabeth (2008), Islamische Plakate. Kalligraphie und Malerei im Dienste des Glaubens, Dortmund.

Saeed, Yousuf (2007), Mecca versus the Local Shrine: The Dilemma of Orientation in the popular Religious Art of Indian Muslims, in: Jain, Jyotindra, ed., India’s Popular Culture. Iconic Spaces and Fluid Images, Mumbai, 76–89.

Schienerl, PeterW. (1986), Koranisches Erzählgut im Spiegel volkstümlicher Buntdrucke aus Ägypten, in: Baessler-Archiv 34.