Field Notes: Performing Bharthari—Change and Continuity in Chhattisgarh

Rekha Jalkshatri arrives for the recording of her performance of the epic of Raja Bharthari on a hot day in the month of March with an all-male troupe in tow. They disband from a van and proceed to change into their ‘costumes’ with a practiced air. Rekha Jalkshatri issues instructions, engages in banter with her benefactors, and applies make-up. She is ready, her troupe members with their orchestra marshal behind her in a semi-circle. The performance begins, and Rekha Jalkshatri sings without stopping for over three hours. She is a riveting performer. Her voice, rich and melodic, cascades and falls to carry every emotion in the pathos-filled tale. The performance is packed with drama—interludes of song draw out emotion, and side conversations with the Ragi comment on the narrative, provide comic relief.

When asked, Rekha Jalkshatri owned that it was she who scripted the storytelling performance, introducing songs and interpretative commentaries by the Ragi to keep audiences engaged.

Genre and Community: The Rise of Professional Individual Artists

Rekha Jalkshatri belongs to the Dhivar-Nishad community of fishermen, somewhat removed from the Jogis, Vasudev and Devar communities or the Pardhans (Gonds) who were bards traditionally. She signals the rise of professional performing artists in this region in post-Independence India, particularly since the 1960s, and with that the rise of female performers in Chhattisgarh. The transition in the performance context of oral epics in this region, previously sung by bards on occasions for communities, to now being performed by professional artists commissioned by state-owned or private agencies, has been gradual. In many ways this been a story both of renewal and loss.

In some ways this has resulted in this tale being performed across communities in recent years. The tale of Bharthari would have previously been performed mostly by the Jogi community who had a particular affinity with this story which sang of the Nath Siddha Jogis, though it is difficult to describe to what extent this tale was owned by a specific social group. The fact that Rekha Jalkshatri could perform this tale, learning it from her grandfather Mahettar Prasad who also sang and recited the tale, signifies the reach and extent to which this tale is now known and recited.

Oral and Literate Cultures

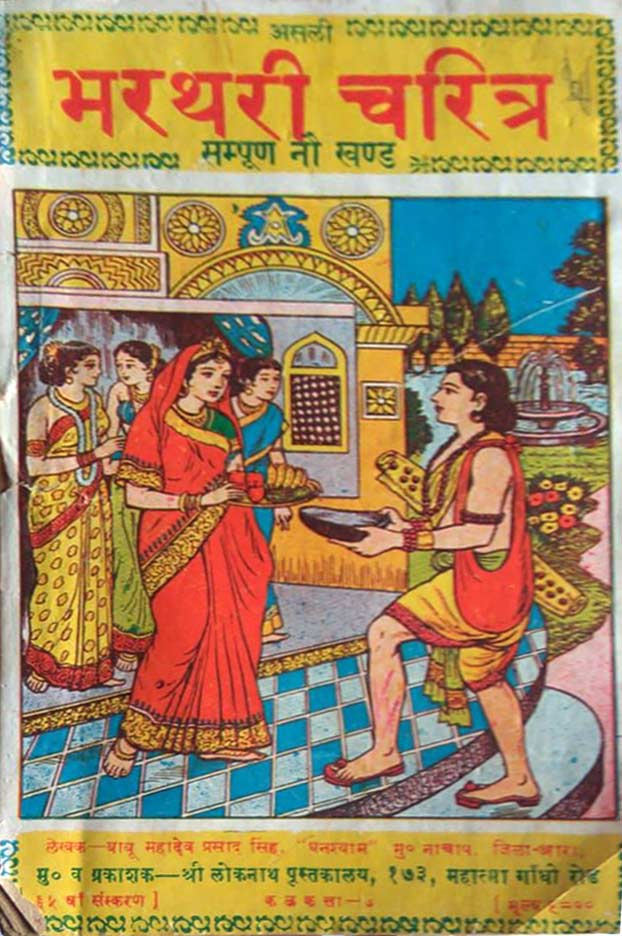

The epic of Bharthari was previously usually sung in fragments, a feature it shared with most other oral epics from this region. While that is still the case, the introduction of professional performance contexts seem to have prompted attempts to piece together the entire narrative relying on textual sources. Rekha Jalkshatri claims that her grandfather took the help of a printed version written by Babu Mahadev Prasad in Kolkata in the 1940s. He and his ragi first translated this version into Chhattisgarhi and then taught that version orally to Rekha Jalkshatri, setting off an oscillation of oral and literate sources and traditions. Did that result in a ‘sanskritization’ of the tale, or a privileging of textual sources? A comparison with other versions of this tale would enable an understanding of changes in the narrative that were brought about. Rekha Jalkshatri's account of her grandfather’s re-scripting of the tale of Bharthari is, at another level, also a story of the reach and pervasiveness of popular print culture as a media.

Singing the tale of Bharthari

Rekha Jalkshatri owns that she was initially drawn to the Pandavani hearing her grandfather Mahettar Prasad recite this genre. She was about twelve years old when she first started reciting the Pandavani, hearing two version of the epic that were in circulation—the orally transmitted version, and the rendition of the tale derived from textual sources (kapalik and vedamati are terms used in Chhattisgarh to refer to these two versions of storytelling, which are rendered in different styles). She, however, turned to Bharthari, prompted by the fact that there were fewer professional singers of this tale. At the time that she started performing another female performer was also receiving acclaim for singing and reciting the tale of Bharthari—Suruj bai Khande. The rise of both these artists, and others, as female performers who sang the same tale, creating a storytelling genre out of what was a fragmented storytelling tradition, forms a compelling story. It is a trajectory that is in some ways unique to Chhattisgarh, particularly for the role played by gender in the rise of professional artists.

There were several mediations that shaped the transformation that took place in the performativity of the epic of Bharthari in the 1960s. Both Rekha Jalkshatri and Suruj bai Khande performed regularly for All India Radio, a factor that influenced their craft. The Indira Kala Sangeet Vishwavidyalaya, Khairagarh, also served as an institution where their craft was moulded to suit the needs of differing performing contexts. An orchestra was added, including the ubiquitous banjo, and costume and ornaments chosen to reflect the identity of a performing ‘folk’ artist from Chhattisgarh.

The recitation of the epic is in metered verses, chhand, interspersed with sections of commentary referred to as bhavartha, roughly translatable as core meaning. During the bhavartha, the performer engages in playful banter with the Ragi who adopts the role of interpreter-commentator, and provider of comic relief. The bhavartha sections serve to localize the tale, draw it into a context that is immediate and relatable. Rekha Jalkshatri is exceptionally gifted at improvising bhavartha asides, emphasizing emotion, drama and pace through these interlocutions. Also drawn into the recitation are Chhattisgarhi folk songs sung according to context and situation—a sohar git is sung when the story turns to the birth of a child, a mangal git when the scene shifts to the context of marriage, or bhajans to invoke prayers.

The Tale of Raja Bharthari as Recited by Rekha Jalkshatri

There are several versions of the Raja Bharthari story which circulate in the region between Rajasthan and Bengal. The narrative recounts the tale of Raja Bharthari’s renunciation of the world after marriage to become a yogi. Recounted below are versions that circulate in the Chhattisgarh region.

Rekha Jalkshatri’s version of the story of Bharthari begins with the plight of Bharthari’s mother who is distraught at being childless. She finally gives birth to a son through the blessings of a Nath yogi who offers her a fruit with powers to help her conceive. At his birth astrologers were called from Benaras to cast his horoscope. The astrologers predict that the child would renounce the world to become an ascetic after the age of twelve. The mother, dismayed, approaches soothsayers and yogis for a solution that could alter his fate, but to no avail. So she arrives at a solution on her own—to marry him off at a young age to prevent him from renouncing the world. On his wedding night Bharthari goes to his wife seated on a golden cot. When he approaches her, his wife bursts into laughter and breaks the cot. Bharthari is perplexed and humiliated. Why did she laugh so hard on seeing him that she broke the cot? What was the reason for her amusement? She refuses to divulge the cause, answering instead that her sister who lived in Delhi would provide the answer, not she. Bharthari waits for a pretext to travel to Delhi. Finally, his sister-in-law gives birth to a child, and Bharthari is invited to be part of the celebrations. His wife advises him to travel in full princely regalia, for her sister was married to the ruler of Delhi. When he finally meets his sister-in-law, Bharthari asks her why his wife had laughed at him on their wedding night. She defers disclosure, and says she will disclose on her rebirth as a pig, and then as a hen and so on for seven lives as dog, parrot, and other fabulous lives. She finally discloses that his wife was, in fact, his mother in his previous birth; this memory made her break into laughter. The revelation causes Bharthari great consternation.

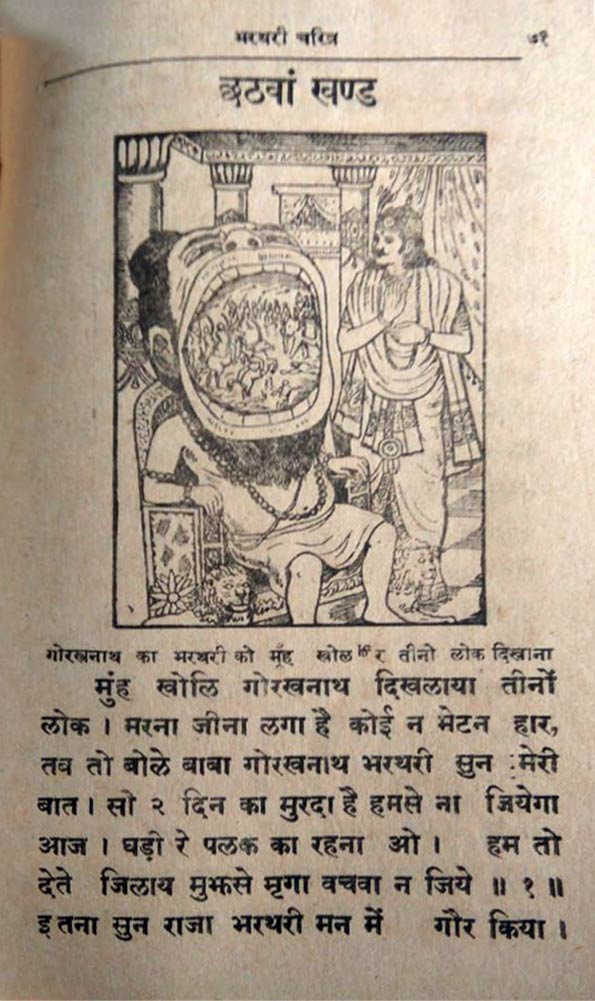

Interwoven into this tale is also a plot that privileges the role of Nath Panthis. The story shifts to the scene of a hunt: Bharthari is off in pursuit of a magical deer. He encounters its spouse who offers her own life and begs him to spare that of her mate. Bharthari, driven by ideals of his caste, refuses and hunts down the deer. A curse is on him now, for this killing. The Nath yogi staves off the curse on Bharthari by restoring the deer to life. Bharthari is moved by a desire to renounce the world and become the disciple of the Nath yogi, Guru Gorakhnath himself. The yogi warns him that the path is not easy—he has to cut off ties with his wife, approach her as a mendicant, call her mother and receive alms. This is not easy. His wife refuses at first but has to give in eventually. Bharthari becomes a Nath yogi.

This article is based on field observations and oral communication with Rekha Jalkshatri, performer of the epic, and experts in folklore based in Chhattisgarh, including Rakesh Tiwari, Ashok Tiwari, and Dr Sonau Ram Nirmalkar.