It is very sad when someone younger than you dies. I am 71 years old and therefore, it is even more difficult for me to digest the death of 64-year-old Namdeo. His death was such a great shock to me, and the reasons for this are personal. We were friends for more than 40 years. From a young age till the end of his life, our friendship was unbroken. There were several political differences between us, but they never came in the way of our deep friendship. Namdeo wasn’t just my friend from the literary world or the movement; he was a family friend. We were with each other in good and bad times. I didn’t go to meet him when he was hospitalised. The reason for this is that I don’t feel comfortable talking to my friends about their illness. But I always got updates from his wife Malika, his driver and his friends. A few days ago, Malika told me that the operation was successful and that his condition was improving. That made me happy and then suddenly, there came the news of his death.

It is difficult to analyse Namdeo’s political and literary life in detail at this moment. But I want to make some observations.

Whenever he called me or I called him, he would always say, ‘Comrade, Lal Salaam, Jai Bhim.’ I will never hear that again. Now, he will never be able to call me again and I won’t be able to call him either. Whenever he gave me his poetry collections or other books, he’d inscribe them to ‘Comrade Satish’. Sometimes, he’d call me dearest, sometimes good friend and at other times, he’d respectfully gift a book to me and my wife.

When he got the Padma Shri, I went with him and Keshav Mishra to Delhi. We stayed with him for three days in a hotel. I travelled with him many times and I saw his love for others and the love of others for him.

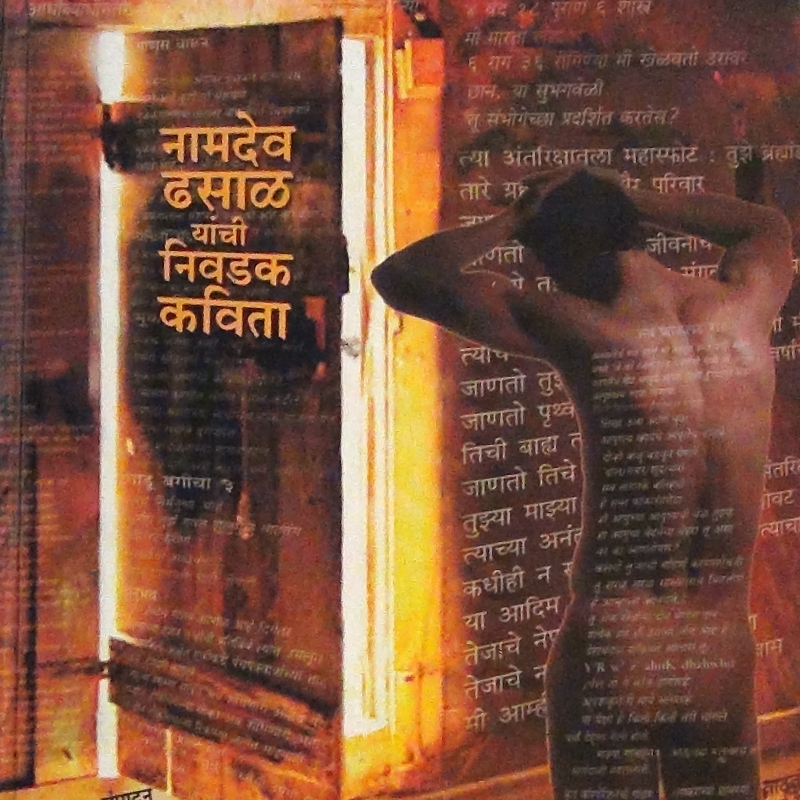

In June-July 1997, Anushtubh magazine had a special issue on Namdeo Dhasal. In it, Pradnya Pawar and I had interviewed him in detail. Because of some reasons, the interview could not be published in its entirety. But Namdeo included it in his poetry collection, Mee Bhayankarachya Darwajyat Ubha Ahe. Pradyna and I worked with him on this collection from evening till after midnight. In it, one can see all the different phases of his poetry.

From Golpitha till today’s Nirvana Agodarachi Pida and Chindyanchi Devi Ani Itar Kavita, one finds that his poetry has evolved. His mission to end casteism and fight for the oppressed connected us in a big way. This was our mission in the early days.

From the '70s to the '80s, the little magazine movement worked actively against the establishment. During this period Namdeo never let go of his agenda—the end of casteism. During the early days, our different caste statuses never came between us. However, different aspects of our caste identities became a problem in the 1980-90s. We shouldn’t go into detail about that but I just want to mention it.

I have always referred to Namdeo as the ‘last Roman of the little magazine movement’. His role in that movement was very important. He spent many of the early energetic years of his life working for this movement. Therefore, his poetry, I feel, should not be limited by small or big terms. His literary achievement should be considered against the broad spectrum of the Marathi language and it should be noted that he was not just a great Marathi or Indian poet but a very important international poet.

We always worked together for the movement and considered each other equals. We attended many events together too, whether it was the three-day seminar on little magazines that he organised or an international poetry festival or just reading poetry together at a cremation ground—we were always with each other.

The relationship of poetry and the individual is a complex one and when it comes to a person like Dhasal, that relationship becomes even more complex and it’s important to study it responsibly. Some people have tried to do this, but it isn’t enough. Many people wonder about how they should read his poetry and his political behaviour together. This discussion has taken place many times. Though one may not be able to understand the relationship between his poetry and his political work, it is important to recognise the wisdom in it.

In his poetry, Namdeo was totally sincere. One can also see that sincerity in his political behaviour, but the important thing is that he never forgot his life-long fight against oppression in his poetry. Take any of his poetry collections and you can see this. Now, to the question of his changing political behaviour. I had requested some our like-minded and learned friends to throw light on this, but that work is never finished. One thread I can see and I’m trying to explore is that of Namdeo’s background, that is, his caste status, the oppressed class to which he belonged, and the world in which he grew up, the world of Golpitha and the Bombay underworld—this should be considered in the conjunction with his understanding of the concept of lumpen proletariat. But this difficult task is not yet complete. And so, what appear to be his sudden and unexpected political jumps, should be kept to one side and we need to look beyond them. If we do not resolve this, then, in the future, there will be many more Dhasals and we are likely to misunderstand them. Thus, we will not be able to understand the role that the lumpen proletariat can play in the struggle or how it can be led astray by caste consciousness and why.

I have tried in my own way to understand Namdeo through his poetry. I wrote a blurb for Chindyachi Devi Ani Itar Kavita and even in that blurb, I have expressed this. Sometimes, I feel that I should analyse it in detail, but I don’t think I have that kind of intellectual capacity. So, my friends who are Leftist and have greater intellectual capacity than me should do this.

In Golpitha, Moorkha Mhatarayane Dongar Halavile and Amchya Itihasatil Ek Apariharya Patra: Priyadarshini, or one can say in his entire oeuvre, he has tried to encompass all classes, all castes, all kinds of workers and farmers. The title of his collection of essays, Sarva Kahi Samashtisathi, does precisely this. So, we cannot say that Namdeo was talking about oppression from a particular caste perspective only. Namdeo has specifically said this in his prose on Dalit Panthers, in his interviews and other writings. To describe Namdeo as a Dalit poet is nothing but a show of our intellectual poverty. He tried to connect his fight to end casteism with the struggle of deprived people of all kinds through his prose, poetry, interviews and newspaper columns. While inscribing the poetry collection Mee Bhayankarachya Darwajyat Ubha Ahe for me, he wrote, ‘Comrade Satish, don’t you think that we can win the class war only after we have won the caste war?’

In the tradition of Marathi poetry, some important milestones have been ignored. The first rebellion started with the Mahanubhava poets, Tukaram and Dnyaneshwar because they fought against the Sanskrit language. Theirs was the voice of rebellion; all the bara balutedars[1] who wrote saint poetry were roused by this sentiment of fighting against oppression. Sanskrit was never a common man’s language and so, they felt that if they wanted to reach the people about whom they are writing, they had no alternative but to use Marathi. There are other reasons for this too. Even so, the period from the 12th to the 17th century was one of the most fertile periods of Marathi poetry.

In the later period, other than a few exceptions, Marathi literature took a turn and once again became the hereditary privilege of the upper castes and upper classes. Then, in the 19th century, there was another rebellion; Mahatma Phule, Maharshi Shinde and Ambedkar made an effort to reconnect the Marathi language with this older tradition of saint writing. Unfortunately, a play by Mahatma Phule called Trutiya Ratna only came to light after a very long time and there is so much writing that hasn’t reached us yet. Then, after the 1960s, the intensity of the first major literary protest against the establishment dimmed. There were exceptions in the intervening period but I won’t go into them in detail. The anti-establishment literary movement from 1960 to 1975 marked the beginnings of Namdeo’s poetry. The style of his poetry, the direction of its thought and its future path were greatly influenced by this movement. Because of this we ought to study the history of Marathi literature of the last 50 years.

I don’t want to say here that Namdeo was born because of his desire to fight the establishment, but that period of his life complemented his poetry and made it bloom. The poems from Golpitha and Moorkha Mhatarayane Dongar Halavile are a testament to those changing times, and the poems evolve and mature to a great degree as can be seen in Ya Sattet Jeev Ramat Nahi and Nirvana Agodarachi Pida. Namdeo’s poetry in the early period seems more aggressive whereas in the later period, it becomes wise and appears mature. His death has deprived us of a poet who made Marathi poetry so rich and we have lost a great poet who had the potential to leave Marathi poetry’s mark on the international map.

This article was first published in the Marathi newspaper Loksatta on January 16, 2014 and has been translated by Subuhi Jiwani and Shashikant Sawant.

[1] The bara balutedars are the twelve castes that were a part of the balutedar system in Maharashtra’s villages. Each caste, from the dominant castes to the (former) untouchable castes, was assigned hereditary duties that it had to perform for the village. In exchange, each caste group received a portion of the village’s total produce or baluta.