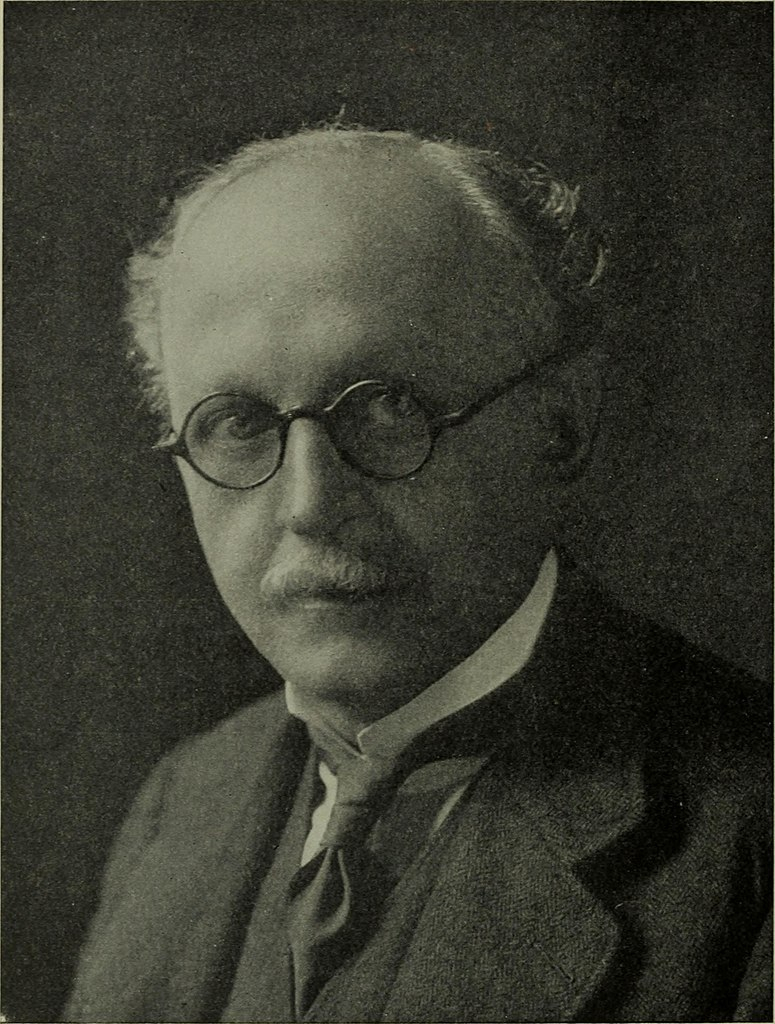

British architect Edwin Lutyens was given the task of designing the Viceroy’s House (which we now know as Rashtrapati Bhavan), and the imperial enclave in 1912. As part of the series ‘Reading a City’, we look back at the master town-planner’s legacy. (Photo Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

Of the many articles and books written about the architecture and buildings of New Delhi (1912–31), the most comprehensive has been Robert Grant Irving’s Indian Summer: Lutyens, Baker, and Imperial Delhi, published in 1981, timed to appear in the golden jubilee year of Delhi. A pity that the book made only a momentary appearance in India, and then vanished from view. The Oxford University Press in Delhi had to suspend the printing of the book because the author had wrongly taken credit for the 80-odd photographs that were the work of photojournalist Dhruva N. Chaudhuri.

Related | Syed Ahmad Khan and ‘Remains of the Great’ Delhi

As a result, this thoroughly researched account of the long process of the building of the only complete city the British left behind in India is not available to students in India. The incredibly dedicated work of Edwin Lutyens (1869–1944), artist-architect and town-designer, and a contemporary of Mahatma Gandhi, gets trivialised—to the extent that it becomes possible to suggest that the tiny enclave popular as ‘Lutyens’ Delhi’ can be modified, height controls given up, and the green cover reduced. Its unique quality, which is part of the international design history from the 1870s to the 1920s, will be lost. As the enclave inches towards its centenary, it has to be appreciated as a unique low-density, eco-friendly landscape. Sadly, Lutyens’ Delhi is inhabited largely by political figures and civil servants, all birds of passage, who have no long-term interest in retaining it.

Modelling Delhi on European Cities

In 1912, Lutyens had two design briefs—the Viceroy’s House (which we now know as Rashtrapati Bhavan) and the imperial enclave. It is rare for an architect engaged to design a palace to be asked also to plan its urban setting. New Delhi was small in size but large in concept—modelled on European Renaissance cities—with a symmetry clearly visible from the air (Lutyens would not have been able to enjoy this view since air travel was still in its infancy), and also on ground in terms of distribution of spaces. At many intersections, in place of crossroads, the signature roundabouts (or gol-chakkars as they are colloquially known) accommodated six roads, and created a sense of wind movement, which softened the harsh climate.

Also read | The interiors of the Rashtrapati Bhavan

In building aristocratic homes in Britain, Lutyens often worked with Gertrude Jekyll, the garden designer, to create arts and crafts-style landscapes that were an escape from the new industrial cities. In India, he was dismayed at the arbitrary manner in which towns had grown, and wanted to bring order and peace into the landscape. He enlisted the help of engineers and horticulturists and wanted to understand Indian skills—he requested that the water channels in the Red Fort be put into operation, and echoed them in the water channels of Kingsway (now Rajpath), with ethereal fountains that replicated Italian Renaissance models. He studied a range of trees before selecting the ones that would be used for each avenue. The overall design is often crudely dismissed as being like a cantonment—the only real similarity is the principle that the allotment sizes correspond to the hierarchy of official positions.

Lutyens’ Uncelebrated Works

Iconic avenues elsewhere—the National Mall in Washington, DC and the Champs-Élysées in Paris—commemorated republics, and Kingsway (now Rajpath) glorified imperial power. There was no Parliament or Supreme Court in its Lutyens’ original design, because these institutions did not exist at the time. The Secretariats were sedate offices where few ‘commoners’ had reason to go. The people at large had two dedicated spaces. The boulevard and the Raisina Hill met at ‘The Great Place’, visualised as an arena for celebrations, but ultimately used only once a year for the Beating Retreat ceremony. The other public place was for the ‘celebration of knowledge’—the crossing of Kingsway (Rajpath) and Queensway (Janpath) to be marked by the Imperial Museum (now the National Museum), the Imperial Record Department (now the National Archives), the Imperial Library, and the Oriental Institute. Sadly, the long hiatus in the construction work because of the World War I meant that only the first two of the knowledge centres—Imperial Museum and Imperial Record Department—materialised.

Also see | Domes of Delhi

Lutyens designed a grand palace, like the cathedrals and stately homes he had built in Britain, but these proclaimed not so much wealth or power as they did the painstaking work of honest artisans. The artisans’ hand-eye coordination can be seen in the details of the structures Lutyens designed. His drawing collection is one of our national treasures—thousands of sheets done by hand, then rolled into metal rollers and deposited not in the Royal Institute of British Architects archives in London but in the Central Public Works Department archives in India where they lie unregarded. This is the legacy of the man who had a blackboard for his dining table, where an engineer or a mistri (labourer) was equally welcome to share lunch with him, and throughout the meal, he thought and talked only of his work.

Who was Edwin Lutyens? Craftsman? Artist? Architect? Town-planner? Caricaturist? All of them.

This article is the fourth of a nine-part series on Reading A City by Dr Narayani Gupta on The Print.