While numerous walks, talks and performances attempt to keep the past alive in the capital city of Delhi, the person who began it all was a young man in his 20s—Syed Ahmad Khan of the Aligarh Muslim University fame. As part of this series on ‘Reading a City’, Sahapedia explores how Khan sees historic architecture as part of a continuous culture, constantly nourished by new infusions. (Photo Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

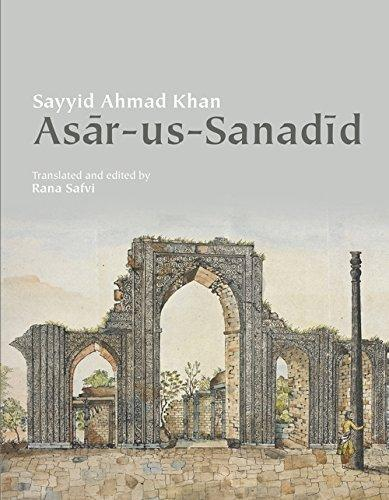

Delhi is puzzled over, introduced, interpreted, celebrated all the time. Walks, performances, talks and articles keep the past alive here. But not many realise that the person who began it all was a young man in his 20s. Two centuries after he was born, Syed Ahmad Khan’s work can now enjoy a wider readership because of its translation into English. His book Asar-us-Sanadid was translated into English by historian Rana Safvi in 2018, for us to revisit Delhi as it was in the nineteenth century.

He was not the first writer to describe Delhi, but when he compiled his notes on the ‘remains of the great’ (asar-us-sanadid) into a book, he chose to write not in Farsi but in the accessible Urdu—making him a pioneer. Another first was that it appeared as a book rather than as a manuscript because his brother had just installed a new Urdu printing press in Delhi. His qualifications to write were not that of a narrow specialist. In those happy days when education was not one fixed menu, he had studied science, mathematics, Farsi and Urdu. In his 20s, living in his family home in Shahjahanabad, Khan was a junior official in the East India Company, helping his brother publish an Urdu newspaper, and translating Farsi manuscripts.

Asar was published in 1847, and had a quality of eagerness explained by his learning the subject as he went along. Khan went to great lengths to transcribe inscriptions (‘He is climbing up with such enthusiasm/That people think he has some work in the sky’ was an affectionate comment about his swinging round the Qutb Minar in an improvised basket-and-poles contraption to read the inscriptions on the higher storeys). The artists’ drawings for the book were based on his own sketches.

Also see | Exploring Shahjahanabad in Old Delhi

There are very few extant copies of this edition. The better-known second edition from 1854 bears the blue pencil marks of the collector A.A. Roberts, who did a hatchet-job, reducing it by a half, adhering to chronology, giving British scientists a role in the Jantar Mantar project, removing all the poets and artists, and making it an altogether dull book.

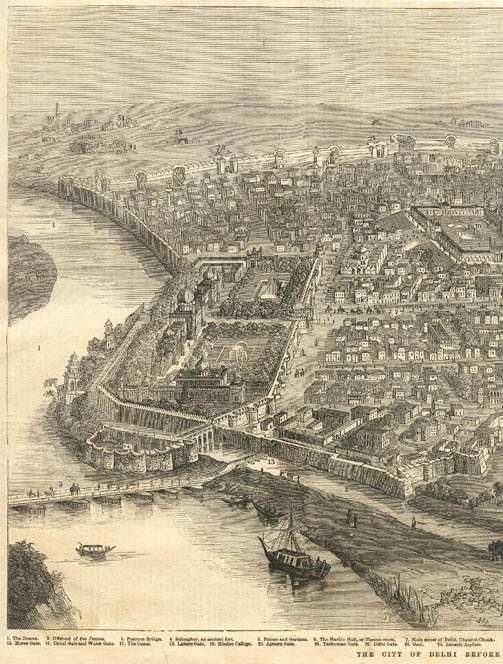

To Khan, historic architecture was not just patrons, materials, form and function. They were part of a continuous culture, nourished by new infusions. Political history, the overlapping cities and forts, the increasingly sophisticated elements in architecture, became four-dimensional by reading mosques, dargahs and mazhars as sacred spaces, calm with the presence of mystics and scholars long departed. They were to be experienced in silence, reading the inscriptions, not listening to the patter of a guide. He delineates the complementarity of a vibrant urban culture—music, poetry and dance—and animated bazaars, and the tranquil atmosphere of the countryside, fields and hills dotted with ruins. ‘The charm of the Delhi scene’, as historian Percival Spear was to describe it a century later.

Also read | Shahjahanabad: Metamorphosis of an Old City and it’s Enveloped Heritage

In a sentence that sounds startlingly contemporary, Khan is distressed by the ‘recent’ increase of the city's population, making it—and also the bracing hills of Mehrauli—unpleasantly congested. But, he insists that ‘in spite of all these factors, the climate of Delhi is still a thousand times better than that of other cities.’ The magnificent Mughal fort (remember he was writing well before 1857) is described in the second chapter, Shahjahanabad in the third, the artists, poets and musicians in the fourth (the section captioned, charmingly, ‘The nightingale-like sweetly-singing people of Shahjahanabad on the outskirts of Paradise’).

It was a challenging task. Delhi’s landscape was not easy to read in the complete absence of any older accounts or images. There was overlap, modification (particularly in the Qutb Minar area), vandalism (of Rahim’s tomb by the ruler of Awadh). As a teenager, Khan was interested in astronomy, so his distress at the neglected condition of Jantar Mantar is understandable. He would have liked to spend more time studying it: ‘I will need a separate book to describe the workmanship, use and effectiveness of these instruments.’

Mirza Ghalib, in the ‘Foreword’, described his friend’s book as one that would ‘numb the hands of other writers.’ Khan’s meticulous account of buildings, even those in ruins, became the template for later books in English. ‘He who undertakes to write the archaeology of Delhi must constantly seek for light in the pages of Syed Ahmed Khan's interesting work on that subject,’ wrote Carr Stephen in The Archaeology and Monumental Remains of Delhi (1876).

Related | Women Patrons and the Making of Shahjahanabad

More than 20 years elapsed between Asar’s second edition and Stephen’s book. A world separated the two publications. Khan, posted in Bijnor (modern UP), was not caught in the trauma of 1857 (the Great Revolt). Some of the poets—like Ghalib—he had listed in Asar sought relief by writing laments to their ravaged city. His own reaction was different. With a sense of grief at seeing an efficient machine derailed, he was to write Asbab-e-Bagawat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian Rebellion) to try to understand what had gone wrong. Khan’s bond with Delhi was severed. He went on to become a distinguished public figure in north India, remembered today for the institution he founded, the Aligarh Muslim University. Hopefully, reading Asar now will return the young Syed Ahmad Khan to us. The past is in many ways a foreign country, and to walk with a guide through towns of the past is an invigorating exercise.

This article is the second of a nine-part series on Reading A City by Dr Narayani Gupta on The Print.