…Responsibility for cultural heritage and the management of it belongs, in the first place, to the cultural community that has generated it, and subsequently to that which cares for it.[1] (Nara Document on Authenticity, 1994)

Basgo, the capital of Ladakh in the 16th and 17th century CE saw a decline in its fortunes when the base of political power was shifted to Leh. In the 19th century, the Dogra army invaded Ladakh. Pillage and plunder followed, rendering the once significant fort and palace to ruins.

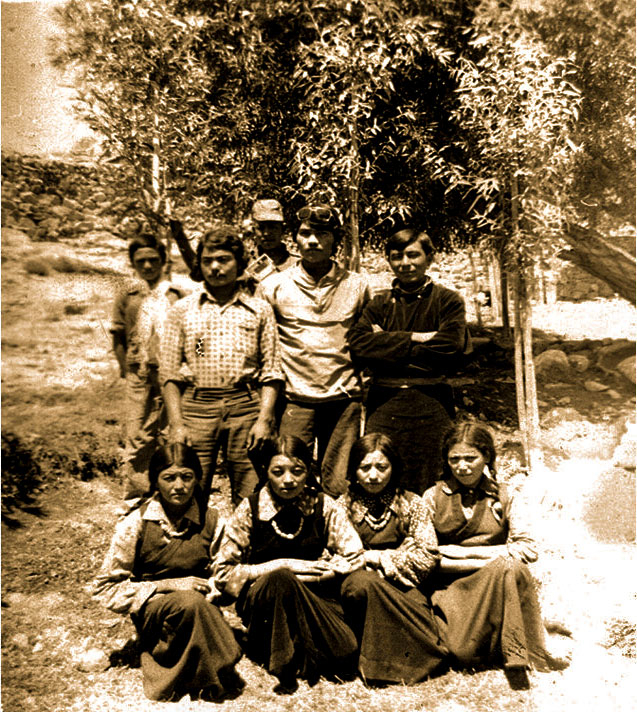

Around the time, when Ladakh was opened to foreigners in 1975, the continued damage to fragile cultural material that had survived for centuries galvanised a small group of youngsters from the village to form the ‘Youth Dramatic Club’ (Fig 1). The club raised funds for the maintenance and repair of the local temples by performing traditional Ladakhi plays based on the Jataka[2] tales besides other traditional repertoire, in and around neighbouring villages. The money collected was utilised for the upkeep of the temples and other developmental goals. With this, the group of youngsters seized the responsibility and pre-empted the inevitable loss of the cultural, social and religious manifest of a rich past and evidence of the trials and tribulations of Basgo—for the future generations of the village and region. They, in the process were also looking ahead to achieve developmental goals in education, healthcare and agriculture[3].

Fig. 1: Members of the ‘Youth Dramatic Club’, Basgo (1976), performed in neighbouring villages to raise money for maintenance and upkeep of the monasteries and other common works. Their initiative inspired a generation to preserve the rich cultural heritage of Basgo. (Picture Courtesy: Tsering Angchuk)

The activities of the Youth Dramatic Club inspired the young children who were growing up at that time, to establish the ‘Basgo Welfare Committee’ (BWC) around 1987, with the stated objective of preserving the tangible and intangible cultural heritage, traditions, arts and literature of the village along with other developmental activities (Fig. 2a). BWC has one nominated member from every household in the village with equal voting rights on all issues, irrespective of landholding or social hierarchy. Another important and unique feature of the committee is to ensure that every member/family participates in every activity of the committee, this ensuring that every member has a stake in the success or failure of common goals (Fig. 2b).

The Youth Dramatic Club thus anticipated and validated a key principle (…responsibility for cultural heritage and the management of it belongs, in the first place, to the cultural community that has generated it...) of the ‘Nara Document on Authenticity’[4] (Nara 1995) by almost ten years. Today this tenet is the keystone of all conservation efforts across Asia, with the subsequent ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) charters expanding the scope of interpretation.

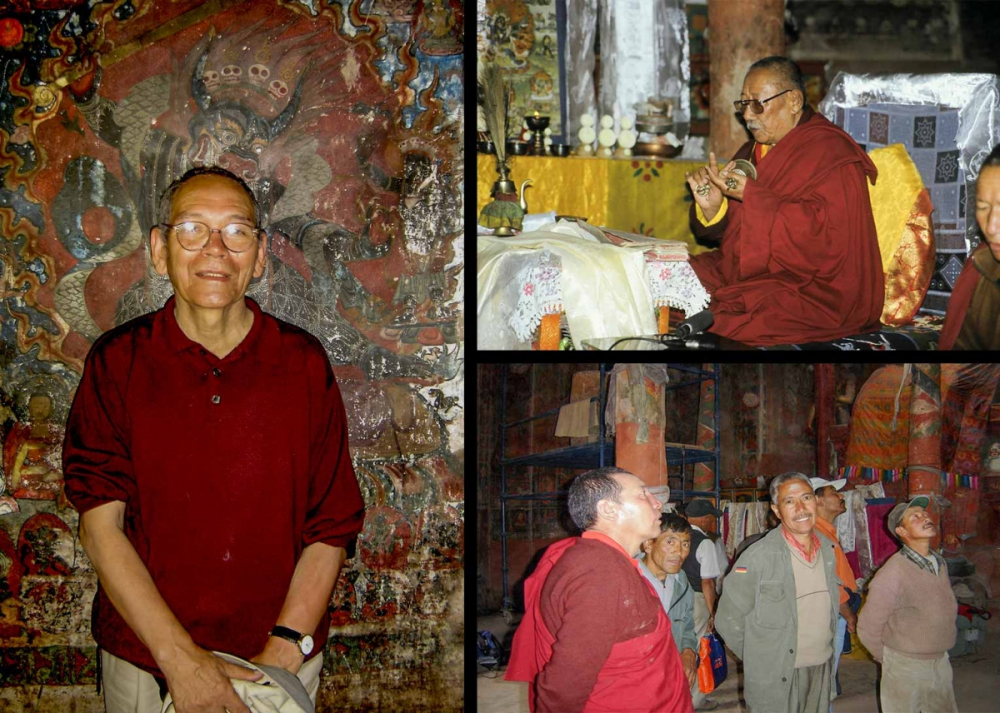

Soon after its formation, the BWC found a mentor in Dr Lobsang Jamspal[5], a highly respected academic from the village, whose achievements and world view were much admired by the young members of the BWC. Under his influence and guidance, BWC first took on the restoration of a chorten and the mane (prayer) wall, on the outskirts of Basgo (Fig. 3a). It was of help, that one of the members, Tsering Angchuk was a civil engineer, who also functioned as the Secretary for many years. Dr Jamspal also helped with several rounds of fund raising for restoration of various structures.

Fig. 3a: Dr Losang Jamspal, with his worldview and understanding provided direction and mentorship to the youth of Basgo, motivating them to take up conservation of the pathway and Cham Chung. b: The Stakna Rinpoche (living Buddha, and the living head of a subsect) provided moral and spiritual support to the Basgo Welfare Committee (BWC), throughout the duration of the project. Here, seen performing the ritual of removing the ‘spirit’ from the paintings before the start of the project. c: Broad based support for the conservation project was built through interactions in particular with influential groups such as the Ladakh Gompa Association. Here, members of the Gompa Association are being appraised of the ongoing work at Chamba Lhakhang. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

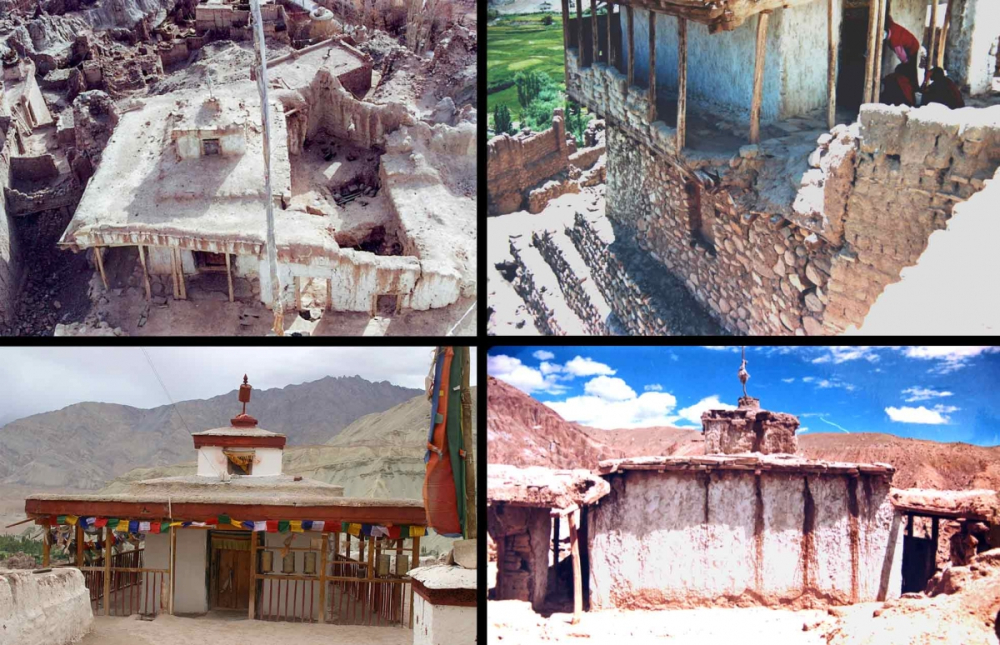

The main challenge for the BWC, however, was the rapidly deteriorating condition of ancillary structures in the fort complex that also threatened the temples with Cham Chung almost at the verge of collapse (Fig. 4a, b & c). The situation was further aggravated due to the fragile nature of the rock of the Basgo hill which was eroding at an alarming rate, exposing the foundations of the Chamba Lakhang. The access to the temples from the village was covered in debris, making the walkway dangerous to traverse (Fig. 5a & 6a).

Fig. 4a: View (from above) of Cham Chung in a dilapidated state, note the extensive damage to the area around the main temple. (Picture Courtesy: Tsering Angchuk). b: View of west face, Cham Chung; several wooden pillars from the circumambulatory have been damaged, portions of the foundation wall have collapsed due to water seepage. (Picture Courtesy: Tsering Angchuk). c: View of east face, Cham Chung; showing extensive damage to the structure due to water seepage. (Picture Courtesy: Tsering Angchuk). d: Cham Chung after structural conservation (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

Soon after the restoration of the Chortens and mane (prayer) wall, BWC initiated the structural restoration of Cham Chung. All around the small temple located at the edge of the lower terrace, portions of the terrace had collapsed, the roof was leaking and the wall paintings were severely affected (Fig. 7a, b). The architectural restoration was taken up after consulting several senior crafts persons and engineers, ensuring that during the process of restoration, the paintings did not get damaged further. The conservation was achieved without any incident; the damaged wall paintings did not suffer further loss (Fig. 4d).

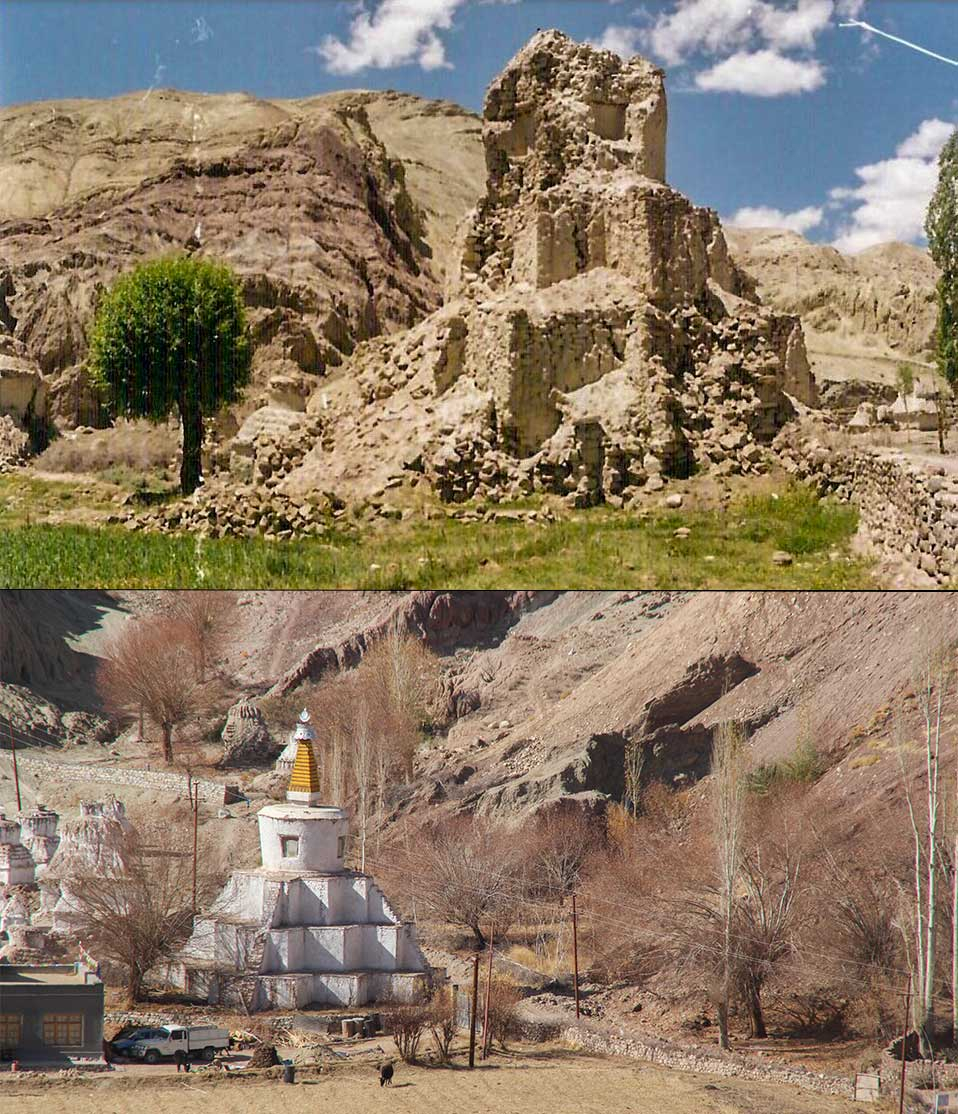

Fig. 5a: South face of Chamba Lakhang; the access to the Chamba Lakhang was precarious with the crumbling rock foundation (before). (Picture Courtesy: Tsering Angchuk). b: The same area after the retaining wall was completed. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

The crumbling rock of the Basgo hill threatened to put a serious question mark on the very existence of Chamba Lhakang, the pride of Basgo. After consultations, it was obvious that unless the area around the foundation was strengthened, all efforts would be futile. Therefore, it was decided to build a retaining wall, wrapping the fragile mountain in stone. This was an engineering challenge, as well as a logistic and financial nightmare. More than fifty percent of the Basgo hill needed to be covered in almost five to eight feet thick stone wall. With Tsering Angchuk taking on a leadership role, BWC devised unique solutions to raise funds. The villagers contributed labour on a regular basis, with an arrangement that one member of each family would work on site for a certain number of days followed by a representative of another family. On holidays and religious festivals, the entire village, and often the neighboring villages were asked to show up on site to move stones from the dump to the site where the build was going on. Material in most cases could not be reached to the build in a truck but had to be carried physically over the difficult terrain to the site where the construction was going on. The BWC requested the army for help with providing transport for carting stones and materials to the site.

Fig. 6a: West face of Chamba Lakhang; the foundation of the temple is exposed due to erosion; parts of the temple wall damaged due to water seepage (before). (Picture Courtesy: Tsering Angchuk). b: The same area after the retaining wall has been completed and after architectural conservation. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

When the project was short of funds and no immediate source was in sight, BWC raised interest free loans from the Basgo villagers and anyone locally willing to lend money. This was a novel approach to manage the project. The rationale for raising private loans by BWC was to ensure that the momentum of such a massive enterprise was not lost, since it would be difficult to mobilise on this scale all over again. The decision to continue and seek private loans was taken at a meeting of the BWC that continued late into the night, with the entire village weighing in. (Fig. 2b). The construction of the retaining wall carried on for 7-8 years, while friends and well-wishers helped with the fund raising. The BWC repaid all the loans over a period of time (Fig. 5b & 6b).

Fig. 7a: Cham Chung south west corner, damaged due to water seepage and foundation settlement. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar). b: Cham Chung north west corner, extensive damage due to structural failure and resulting water seepage. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

In order to raise more funds towards the end of the last millennia, application for nomination to World Monument Fund (WMF) list of most endangered heritage sites was filed. However, initial applications did not meet the criterion. In 2002, The Namgyal Institute for Research in Ladakhi Art and Culture (NIRLAC)[6] partnered with BWC, with assistance from INTACH for preparing a professional, technical project report to help with the nomination to the WMF list, and also for additional fund raising. Basgo was twice nominated to the WMF’s ‘most endangered’ list, which helped raise funds for the architectural[7] and paintings conservation[8] of Chamba Lhakhang. It was also for the first time in the country that separate funding and time was provided, for the purpose of detailed documentation and condition assessment of wall painting.

The original plaster with the painting had detached in several places, connected to the wall by a tenuous link. Similarly, the paint layer was flaking in many places. All these areas were vulnerable to vibrations and activity during the building conservation. Therefore, emergency treatment of the paintings was carried out to ensure that during structural restoration no further damage occurred (Fig. 8a). Architectural conservation was a collaboration with the wall painting conservation team, in order to ensure that the paintings did not get affected, and help was at hand in case of any problem. Materials for conservation was sourced locally as far as possible, in order to help establish a methodology for future projects (Fig. 9a & b). The project has been a training ground for everyone involved but specifically for a large number of young professionals in architectural and wall painting conservation. Some of the locals who were involved continue to work with heritage professionals elsewhere in Ladakh.

Fig. 9a: West wall, Chamba Lhakhang before conservation. b: West wall, Chamba Lhakhang after conservation. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

Along with the ongoing work inside Chamba Lakhang, a small grant from UNESCO helped begin conservation work on the wall paintings of Cham Chung (Fig. 11 & 12), in 2004 (Fig. 10). The project was completed in 2005. Some repair work was also carried out in the Chamba Serzang[9]. The site hosted a UNESCO workshop on conservation of mud architecture, conducted by international experts and participants from four countries.

Fig. 10a: North wall (above entrance) before conservation. b: North wall (above entrance) after conservation. Areas where information regarding the painting was lost were left blank. In other portions, attempt was made to recover as much of the visual information as possible using various scientific techniques of painting. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

The Chamba Lakhang, Basgo conservation project[10] has received a lot of attention at the local, national and international level. Various aspects—particularly technical and ethical issues of conservation in living monasteries have been key to this engagement. The conservation work has been documented in detail with several publications detailing the process and the various ethical issues and their resolutions[11]. The herculean task of cladding a hill in stone to prevent the foundations from deteriorating further would deter governments and agencies with unlimited funding and technical resources. BWC did it on a budget and then took up more challenges. They recognised the role of scientific approach to conservation, which reflected in the manner the paintings in Cham Chung had been left untouched after completing the structural repairs—almost a rarity in the region[12].

However, it is not the technical management, or even social involvement that makes this project unique. The outstanding significance of what has been achieved at Basgo is to demonstrate convincingly that heritage management and preservation can only succeed if ‘pride in ownership’ is asserted by those that are closest to it physically, intellectually and emotionally. BWC found solutions to many of their problems by utilising their traditional social and cultural value systems to take forward into the future more cultural material in good condition, than what they had inherited (Fig. 13).

Works cited

1. 1994. The Nara Document on Authenticity. (Online at: https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf)

Endnotes

[1] The Nara Document on Authenticity, Japan, 1994, Section titled: Cultural Diversity and Heritage Diversity, No. 8

[2] Stories from the previous Lives of Buddha

[3] Verbal communication; Tsering Angchuk, Secretary BWC

[4] The adoption of the Nara document in 1995, resulted in ‘tectonic’ shift in the cultural sector recommending an engaging and holistic approach to conservation. At the time, cultural material and its preservation was predominantly focused on the material well-being of a monument based on a Western model, and all decisions favoured material over people. This model failed to consider situations in living heritage with intangible associations etc.

[5] From the village, was ordained a monk who studied in Tibet till the borders were closed in the 1950s. He then studied at Benares Sanskrit University, from where he migrated to the USA. He taught at the Columbia University and at the Tibetan Translators’ Guild.

[6] NIRLAC was the lead agency for coordinating technical and financial support for the project.

[7] The conservation of wall paintings was done by the author along with his team, for two seasons. The project was completed by Art Conservation Solutions, New Delhi.

[8] The project report was prepared by Divya Gupta (Conservation Architect); and by Abha Naryan Lamba Associates, Mumbai, the lead architectural consultant with BWC taking on the role of site management and as contractor for the project.

[9] The wall paintings have not been restored yet, due to lack of funds.

[10] The project in 2007 won the UNESCO Asia Pacific Heritage Award of Excellence in recognition of the community’s stewardship of its heritage.

[11] See suggested reading.

[12] In many villages along with the building repairs, damaged old wall paintings have been removed to be replaced by new works, leading to loss of historic paintings in the region.

Additional Reading

Dhar, Sanjay. ‘Challenges in the Context of the Living Sacred Tradition of Mahayana Buddhism’. In The Object in Context: Crossing Conservation Boundaries: Contributions to the Munich Congress, 28 August-1 September, edited by David Saunders, Joyce Townsend & Sally Woodcock. London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 2006.

Dhar, Sanjay. ‘Documentation and Emergency Treatment of Wall Paintings in the Chamba Lakhang (Maitreya temple): Developing a Methodology to Conserve Mural Paintings in India's Ladakh District’. In Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China, June 28-July 3, 2004, edited by Neville Agnew. Los Angeles: GCI, 2010.

Jamspal, Lobzang. ‘The Five Royal Patrons and Three Maitreya Images in Basgo’. In Recent Research on Ladakh 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Colloquium on Ladakh, Leh 1996, edited by Henry Osmaston & Nawang Tsering, 139-156. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsi Das Publisher Pvt. Ltd., 1997.

Haq, Sama. ‘The Monastery-Fortress of Ladakh: A Case Study of Basgo Gompa (15th - 17th Century CE)’. In Himalayan and Central Asian Studies 20, no. 2 (2016):74-88

Haq, Sama. ‘Basgo Gompa Across Time’. In Indian Horizons 63, no. 1 (2016):60-68.

Sharma, Tara and Weber, Mark. ‘Temple Guardians: A Community’s Initiative in Conserving its Sacred Heritage’. In Context: Built, Living and Natural VIII, no. 1 (2011):77 -84.

Lambah, Abha Narain. ‘Restoration of the Maitreya Buddha Temples, Basgo, Ladakh’. In Marg 59, no. 2 (2007):66-69.