Basgo, with its half-ruined temples and castles built on precipitous cliffs, and the quaint huts of the modern village that cluster between the sanctuaries and the sandstone rocks, makes a deep impression on the visitor; and I still cherish in my memory the picture of this ancient corner of westernmost Tibet. (Roerich 1931:18)

Introduction

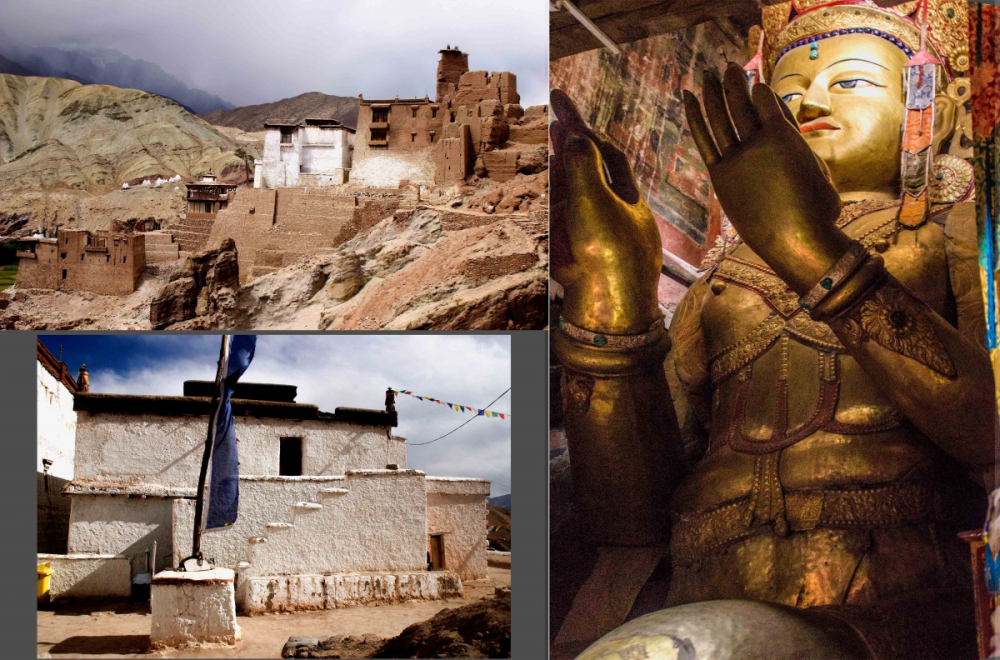

Basgo (Ba sgo)[1], is an agrarian village comprising around 150 households, located on the National Highway connecting Leh, the district capital of Ladakh, to Srinagar (NH 1D), about 35 km from Leh. A historical site, Basgo, was once strategically located on the trade route (with access to the Silk Road and Kashmir) at the juncture of Upper and Lower Ladakh, and used to be the final staging point for caravans and travellers. Hardly any recorded travel account through Basgo fails to acknowledge the impact of the natural and built configuration that the travellers confront, at the edge of the barren plateau, before descending into the valley (Fig. 1).

The village is spread around the base of a dark red spur, running perpendicular to the northern mountain range. This predominant geological feature always created a natural defendable barrier that helped in restraining the movement of invading armies, thereby significantly enhancing the political and military profile of Basgo through most of the recorded history of Ladakh.[2]

Within a radius of two kilometres, one encounters the remains of an ancient fort, three temples with beautiful paintings, ruins of a royal palace, animal stables, residence of ministers and nobility, and a large number of chortens (stupa) of varied shapes, size and antiquity. The remains of a temple dating back to the 11th century, and a chorten (stupa) associated with Rinchen Zangpo (Rin chen bzan po; 958–1055 CE), the great translator, are a testament to the antiquity of Basgo (Francke 1914:88; Luczanits 2005:65–96). The unique excess of historical and cultural material covering a period ranging from the 11th to almost the 18th century contributes to the overall cultural significance of Basgo (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Relief stone stele, dating from around 10th–14th century CE, assembled at the base of a flag post in the village. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

Basgo had gained political importance towards the end of the 15th century with the establishment of the second Ladakhi dynasty. The fort stood witness to significant historical events such as the three-year siege (Francke 1925:115) and the formative events that preceded the ‘golden age’ of Ladakh under King Senge Namgyal (Sen ge rnamrgayl; reign/r.1616–42).

Historical background

In the early 15th century, Raspa Bum (Grags pa bum lde, r. 1410–40) ruled Ladakh from Shey (a village located 15km away from Leh) and was reputed according to The Chronicles of Ladakh to be a great builder, generous in his support to religious institutions. He received the first Gelugpa emissaries at his court and subsequently commissioned the building of the first Yellow Hat Monastery at Pitub (Spituk). One passage in The Chronicles of Ladakh describes him as having commissioned a temple (the description similar to the Chamba Lhakhang), though the name of the place is not given.

In the first quarter of the 15th century CE, Raspa Bum (Grags pa bum) (designated Chief of Basgo) received Basgo as part of a political settlement with his brother Raspa Bumde (Grags pa bum lde), who ruled Ladakh from Shey (c.1410–1440). The chronicles describe Raspa Bumde as a builder and great patron of religious institutions. One passage in the Chronicle describes him as having commissioned a temple (the description similar to the Chamba Lhakhang), though the place where the temple was constructed is not mentioned, leading to some uncertainty about the dates of construction and patronage. Raspa Bumde played a significant role in the establishment of the newly formed Gelugpa order when he received the first emissaries to Ladakh.

Raspa Bum as the Chief of Basgo, reasserted the political space that eventually brought Basgo into the limelight for a long time to come (Petech 1977:25, 171). His grandson, Bhagan (c. 1460–85), deposed the son of Raspa Bumde and his ascension marked the start of the second Ladakhi dynasty. With the shift in the seat of power, building activity in and around Basgo increased. An inscription found in the Gonkhang on Namgyal Hill in Leh records that Tashi Namgyal (bKra sis rnam rgyal; c.1555–75) commissioned a monastery near the Royal Palace (Rab bratan lha rtse) at Basgo (Francke 1925:102; Petech 1977:30). Tsewang Namgyal (Tshe dbang rnam rgyal, r.1575–95), son of the deposed brother of Tashi Namgyal, occupied the throne of Ladakh next, and became one of Ladakh’s most prominent rulers. His military campaigns extended across the borders to Ngari, Purang, Kulu and Guge. He also commissioned the painting inside the Chamba Lhakhang, as per the information recorded in an inscription on the Royal Panel (Bue 2007:189).

Tsewang Namgyal was succeeded by his brother, Jamyang Namgyal (Jam byans rnam rgyal, r. 1595–1616). However, he was soon put to the test by a rebellion from the regional kingdoms keen to assert their independence from Ladakh. This was followed by a long war with Ali Mir, the Chief of Skardo. Besieged and defeated, Jamyang Namgyal was taken to Skardo in ‘honourable confinement’ (Petech 1977:34). While in captivity, he married Gyal Khatun (rGyal Khatun), his caretaker, and daughter of Ali Mir. The alliance made it possible for him to return to Ladakh.

His experience with war and captivity led Jamyang Namgyal towards religion. Though a follower of the Yellow Hat sect, he invited Stagsan Raspa (sTag tsan ras pa; r.1574–1651) of the Drugpa Kagyupa lineage who was reputed to be a siddha (enlightened being) having met all the mahasiddhas. Stagsan Raspa was travelling in the Zanskar (Petech 1977:35) and could not meet Jamyang Namgyal, who passed away soon after sending the invitation. However, this simple act of extending an invitation to a siddha is recognised as one of the greatest political and religious acts of importance in the history of Ladakh.

After Jamyang’s death, Gyal Khatun played an active part at Basgo on behalf of her elder son, who died young and was succeeded by his younger brother, Senge Namgyal. Senge started a successful military campaign to restore the kingdom to its former glory—bringing Guge, Purang and other parts back in the fold of the kingdom. He married Kalzang Drolma (Bskal bzan sgrolma), a princess from Rupshu (Ru sod), whose name is also associated with the small temple, Cham Chung, at Basgo (Francke 1925:108). David Snellgrove and Taduesz Skorupski, while quoting an inscription found in the small temple, date the consecration of the temple back to 1642, by Kalzang Drolma, who is also referred to as Goddess Tara in several other inscriptions (Snellgrove and Skorupski 1979:97). Jamspal contests this account by identifying the Balti princess referred to as the patron of Cham Chung as Gyal Khatun, the mother of Senge Namgyal (Jamspal 1997:151–52; Petech 1999 [first published in 1937–39]:138). She is also believed to have favoured the Yellow Hat Gelugpa sect, thus accounting for the image of Tsonkhapa (the founder of Gelug order) in the small temple.

Fulfilling his father’s desire, Senge also invited Stagsan Raspa to Ladakh and the latter, on arrival, took on the role of the spiritual teacher of the King and secured his support for the Drugpa Kagyupa. He set up several major monasteries, with Hemis monastery as the centre of the Drukpa Kagyupa in Ladakh. Within a short period, Raspa, with the support of the King, managed to increase the Drugpa Kagyupa following in Ladakh. At Basgo, Senge Namgyal commissioned the two-storey tall copper/gold Maitreya statue (Francke 1925:108), close to the royal palace in the temple popularly called the ‘Serzang’[3].

After Senge Namgyal shifted to his new palace in Leh, Basgo lost its pre-eminent position, although its strategic significance was reasserted many times thereafter. It was with the arrival of the Dogra General Zorawar Singh from Kashmir in 1834 and the subsequent pillage of the Basgo fort by his soldiers that the site finally went into decline, with only three temples surviving, having borne witness to almost 800 years of Ladakhi history (Francke 1925:126).

The built heritage (architecture)

Military architecture

Basgo Khar (Fort)

The ruins of rammed earth towers with triangular loopholes and sections of the fort wall dominate the skyline, and give Basgo Hill its unique character (Fig. 3a). The fort was designed as a self-contained township with the capacity to withstand a siege almost indefinitely. This was achieved by creating a multi-tiered fortified settlement utilising the geological advantage of the site to the maximum (Howard 1989:227–37). A series of independent watchtowers of rammed earth with triangular loopholes located strategically at the highest points of the landscape formed the outermost layer. This was followed by a wall all around the perimeter to the south and east of Basgo Hill. Only some sections of the wall are extant today. Important structures like the royal palace were further isolated by an intermediate wall, of which little survives (Fig. 3b). Each of the important structures further had an independent defence strategy with controlled access to these areas. The fort defence also integrated natural features by locating important structures strategically across the Basgo Hill. The walled area also has ruins of structures for storing food grains, and for secure access to a perennial water source in the mountains, close to the site. This feature (water source) alone is responsible for the military reputation of the fort. These features added to the formidable reputation of the fort. All these features of the Basgo Fort were tested during a three-year siege[4] by the Mongol/Tibetan army that ultimately failed after the king managed to garner support from the Governor of Kashmir (Petech 1999 [first published in 1937–39]:156–57). Along with the palace and the temple, the fort also has what is referred to as ‘stables’[5], and the house of the Kalon (minister) is a good representation of Ladakhi vernacular architecture (Fig. 4) besides several other ancillary ruined structures.

Fig. 4: The ministers’ (Kalon) house, a fine example of vernacular architecture/In the background ruins of other residential and ancillary structures. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

Secular Architecture

The royal palace

The eastern face of the fort complex is dominated by the ruins of the royal palace (Fig. 5) (Francke 1925:102). The ruins suggest that the palace was multi-storeyed—and the lower floors constructed with dressed stone laid in the precise course highlight a detailed Tibetan craftsmanship. Heavy timbre, interlaced with dried mud bricks, has been used for the upper floors.[6] A small section of the palace wall extending to the very top, and a small part of the original roof over a balcony, have survived. These surviving parts of the ruins give us an idea of the scale of the structure (Fig. 6). On a ledge at the top of the balcony is a lato (collection of branches to ward off the evil eye); which is renewed in a ritual function annually. This feature and space are prominently depicted in the Royal Panel in the Cham Chung.

Fig. 6: Section of the royal palace with part of a balcony (with lato [collection of branches to ward off the evil eye]), and the surviving roof. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

Religious Architecture

Chortens

Basgo has a rich representation of chortens in various shapes, sizes and antiquity. A dense line of chortens runs along nearly the entire length of the village. Another cluster of early chortens, from the 13th to the 14th century, occupies a small outcrop close to the approach road leading to the fort complex. A stepped chorten (ladder type) with a star-shaped base at the east end of the village, is particularly significant, as the construction is attributed to Rinchen Zangpo (Fig. 7) (Francke 1914, 86)[7]. Another significant chorten is located close to the base of the Basgo Hill, near what would have been the traditional entry to the fort complex. This is a kakani (passage) chorten[8], open on all four sides (Fig. 8a). The wooden ceiling and the walls above the openings have remnants of exquisite paintings similar to small Buddha-like figures in multiple rows. The faint traces of the surviving original paint suggest an early 13th–14th century painting (Luczanits 2005:69) (Fig. 8b).

An 11th century temple ruins

Close to the western limit of the village, about 50m off the main road, are the ruins of an ancient temple (Francke 1914:86) (Fig 9a). Today, only four walls made of sun-dried mud bricks stand witness to a grand temple of the early typology. The walls of the interiors have plug holes and remnants of clay relief roundels that served as halos for sculptures. Such an arrangement is seen only in the early temples, such as at Tabo, with clay sculptures hanging on wooden pegs fitted into the peg holes. The arrangement of the plug holes and the size of the halos suggest a Vajradhatumandala. The area where sculpture of Vairocana Buddha (main deity of the Vajradhatumandala) would have been seated on a throne along with attendant deities can also be identified (Fig 9b). This information has been extrapolated by a detailed study of plug holes and halo sizes, further helping in establishing the date of the structure to the 11th century (Luczanits 2005:70–72).

Fig. 9a: External view of the 11th century CE temple located on the western periphery of the Basgo village. b: View of the enclosure with evidence of peg holes and the raised halo behind the sculpture, the arrangement suggesting a Vajradhatu Mandala. (Photo Courtesy: Sreekumar Menon)

The three Maitreya (Chamba) temples

Despite the excess of significant historical and architectural material today, the reputation of Basgo rests on the three Maitreya temples with the exceptional sculpture and paintings within the walls of the fort complex.

Chamba Lhakhang

The largest of the three Maitreya temples, the Chamba Lhakhang is nestled at the highest point in an alcove of ancient rammed earth fort walls. The Lhakhang is aligned on the north-south axis, abutting an ancient tower at the north-east corner, resulting in the unique ‘boot’ shaped profile of the temple (Fig. 10a). In the North, the old wall has been appropriated, whereas all the other walls are built of mud bricks with mud mortar. The space between the old fort wall and the temple wall on both the eastern and western sides has been utilized to accommodate extra rooms and the staircase leading to the upper floors. A false facade on the first floor, with windows and short ancillary wings on either side of the main chamber, accentuate the sense of monumentality.

The Lhakhang is almost square in plan, with the ceiling rising to about 5.5m. Over a small cut-out in the roof where the Maitreya is seated, a 4m (lantern/sky light) structure accommodates the shoulders and head of the Maitreya sculpture (Fig. 10b). The position of the head above the roof level ensures that the protective gaze of the Maitreya covers the maximum area of the village.

The roof is laid with wooden purlins across painted beams and covered with painted wooden slats. Over the slats is a layer of birch bark (now rarely used) that is covered with compressed clay.[9] The structure around the Maitreya’s head and shoulders is wooden with the roof laid in the traditional style with purlins and willow sticks.

Over the years, there have been several changes to the structure. The ancillary chambers to the east had collapsed during the latter part of the 1970s and this area was restored in the early 1980s by the Basgo Welfare Committee. The first floor was originally covered with a roof. However, today, the structure has only one level—that of the Lhakhang. It appears that the upper floors were removed to reduce the load on the structure—and also with the shift of the capital to Leh, and subsequent pillage during the Dogra wars in the 19th century, there was little need for extra space.

Cham Chung

At the edge of a terrace below the Serzang temple is an unusual structure popularly known as Cham Chung (Fig 11a)[10]. The structure resembles a Balti (or Central Asian) mosque, with the typical conical roof over a square central lantern rising above the main roof (Fig. 11b)[11]. The structure is located on a wooden platform that hangs over the edge, held up by wooden pillars and a random rubble masonry wall. A wooden balcony runs all around the main mud-brick structure, accentuating the mosque-like appearance and providing space for circumambulation.[12]

The small structure (approximately 2.6 x 3.75m) houses a Maitreya sculpture seated cross-legged on a rectangular platform, facing north (Fig. 11c). The head of the sculpture rises into an opening into the skylight (1.5 x 1m). The three sides of the ‘neck’ (approximately 1.15m) of the lantern are also covered with wall paintings. The northern face of the lantern has an opening for the Maitreya to look outwards—towards the Serzang Royal enclosure and Chamba Lakhang.

Chamba Serzang

The temple of Chamba Serzang is located next to the royal palace on the lower terrace, facing east (Fig. 12a). A narrow passage below the temple leads up to the palace; while the main access to the temple complex is shared with the royal palace. The guarded and restrictive access to the temple suggests that the Serzang was meant for exclusive use by the royal family (Fig. 12b).

The Lhakhang is located on the east-west axis, facing east, with the foundation and ground floor of the structure on a lower terrace. The access to the Lhakhang is through a stairway that descends to the lower level from the upper terrace in front. This is an unusual arrangement since the main entrance to the Lhakhang is not visible. Another staircase at the front leads to the first floor which has a partially covered gallery with an open courtyard. The access to adjoining spaces for the monks is through the courtyard on this floor. This unusual arrangement at various levels to control and manage access reaffirms the observation that the temple was used only by the royal family.

The main temple structure is free-standing, with the lower part constructed in dressed stone and the front with sun-dried mud bricks and mud mortar interspersed with horizontal wooden members.[13] The facade on the east is very unassuming with only a small wooden door.

The main Lhakhang is approximately 10 x 11m, and the ceiling is at a height of about 3.5m, held by six heavy wooden pillars with carved capitals, arranged in two rows. In some parts of the Lhakhang and in parts of the upper courtyard portions, the original arga floor has survived[14].

The Chamba Serzang (or Golden Maitreya statue) is an iconic statue associated with four historical figures of Ladakh, its conception and commission finding a mention in the Royal Chronicles of Ladakh (Francke 1925:108) (Fig. 12c). Jamgyal Namgyal wanted to have a metal-cased Maitreya sculpture at Basgo but did not live long enough to complete the project. After his death, Senge Namgyal commissioned the construction of the statue along with his mother Gyal Khatun, and his spiritual teacher Stagsan Raspa, who laid out the iconographic program in the temple.

Wall paintings

Painted heritage

The study of wall paintings from around the 16th century is a challenge due to the lack of support in terms of quality documentation and consistent academic interest, resulting in poor research and limited publication on the subject. This problem is also in part a result of the fact that Tibetan Buddhist paintings are spread over a large geographical area with poor access due to restrictive political boundaries.[15] In the past, the movement of people and ideas, even if difficult and hazardous, was almost unfettered. Travelling artists, crafts persons, and potential patrons (monks and tradesmen) would take in a range of visual impetus and material, that would then be expressed in new ways, on return.

For the purpose of grouping, stylistically similar paintings, and establishing tentative timelines; a simplistic classification of wall paintings in Ladakh can be based on the introduction of the Central Tibetan idiom roughly around early16th century CE[16].

Christian Luczanits has classified the period up to the 16th century CE on the basis of stylistic affinity and proximity to the paintings, in the Sumstek[17] (date 1200–1220) at Alchi. He has named this early style of painting as the ‘Alchi painting style’[18]. This was followed by a distinct localisation of Central Tibetan elements, best examples of such are in the Guru Lhakhang, Phiyang and in the Saspol Caves. Luczanits calls this localised style the ‘Ladakhi Painting style’[19]. One important feature of the Ladakhi painting style which continues till the 16th century CE, is that most of the sites where one observes this localisation are affiliated to the Drigungpa Kagyupa sect. The paintings of this period though classified on a broad ‘stylistic’ basis, in fact do not share common features that usually define a style—rather, it is the complete absence of a consistent use of vocabulary and an attempt to achieve (accidental or otherwise) a different visual aesthetic that marks this important period.

Towards the end of the 15th century, the dominant Central Tibetan Buddhist religious orders found the political environment conducive to the establishment of their monasteries and orders in Ladakh. They built new ones, and often took over old establishments.[20] They brought Central Tibetan artists with them as well as thangkas that served as models to introduce a fully developed Central Tibetan idiom. The paintings in Chamba Lhakhang mark this transition from a native idiom to a fully formed Central Tibetan style of painting for perhaps the first time (Snellgrove and Skorupski 1979:95). This change also coincided with the arrival of Stagsan Raspa and the Drugpa Kagyupa order at the Namgyal court.

Lo Bue on the basis of his study of inscriptions suggests that the paintings in the Tsug Lhakhang at the Tashi Choszang monastery in Phiyang belong to the same period as the Chamba Lhakhang, Basgo (Lo Bue 2007:188). Further, the inscription on the Royal Panel at Basgo also gives the name of the artist who painted both at Chamba Lhakhang and Tsug Lhakhang, Phiyang, as Pon (a title for ‘painter’) Dondrup Lepa (Dpon Don grub legs pa) from Spituk (Lo Bue 2007:189). He has identified several other painters who had worked at Phiyang, all from different parts of Ladakh. These artists were probably trained outside Ladakh in order to become familiar with and be able to execute paintings in the fully developed Central Tibetan style. I discovered a thangka in Basgo similar to one of the wall painting panels. Its existence suggests that before starting work on the wall, the artist would prepare a painting on a cloth to show to the patron and also to use as a model. Another possibility is that artists or patrons brought such thangkas from Central Tibet as models for local artists to copy.

The paintings in the Cham Chung and the Serzang follow a similar trajectory, with the Central Tibetan elements and style becoming more prominent. However, religious developments favoured a more esoteric tantric Buddhist tradition of the Vajrayana along with the increasing popularity and following of the Drukpa Kagyupa order. There are two factors that heavily influence the subject of the paintings at Basgo—the fierce deities at the Cham Chung, and the Drukpa Kagyupa lineage gurus at the Serzang.

I. Chamba Lhakhang

The best preserved (chapels with paintings) are at Alchi, near the bank of the Indus not far from Basgo; then comes the one at Basgo itself, inside the enclosure of the ancient ruined castle. (Giotto 1933:68)

The royal interest in Basgo was maintained, for he [Tsewang Namgyal] had built there a new Maitreya Temple, which after Alchi is perhaps the most beautifully painted temple in Ladakh. (Snellgrove and Skorupski 1979:85)

Separated by almost 50 years, it is perhaps no coincidence that Giotto, a naturalist, and Snellgrove and Skorupski, both Tibetologists, make similar observations about the late 16th-century wall paintings in the Basgo Chamba Lhakhang.[21] It is hard to remain unmoved by the sheer scale of the seated Maitreya within the Lhakhang, the high ceiling (almost 5.5m) held up by four slender painted columns that accentuate the visual impact. The walls are covered in luminescent colours and the use of gold is liberal as befitting a royal temple (Fig 13a). An inscription on the Royal Panel identifies Tsewang Namgyal as the patron for the paintings.

Fig. 13a: A Tathagata figure in the vitarka mudra with a bowl resting on the lap (east wall). In the frieze depicting Life of Buddha is a beautiful depiction of Mara’s attack and the depiction of the achievement of Buddhahood. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

The painted stucco sculpture of Maitreya, seated in an offset (approximately 3 x 3m), dominates the room. The legs extend nearly 3m into the main Lhakhang with the feet almost touching the pillars. The sculpture of slender proportions, rises over 8m into the lantern. He is flanked on either side by freestanding figures (approximately 1.25m tall) of Bodhisattvas Padmapani and Vajrapani. The stucco figures are adorned with foliated crowns, jewellery and richly painted garments. The walls of the offset have a coloured sketch depicting the 1,000-armed Avalokiteshvara, and some fierce deities.

The layout of the paintings in the Lhakhang exhibits a high degree of geometric precision that contributes to its overall visual impact. Close to the ceiling is a band that runs horizontally, filled with undulating coloured festoons held in the mouth of a Kirtimukha (an auspicious motif depicting a ‘face of glory’) with alternating sun and crescent moon symbols. On the bottom is a band illustrating the Life of the Buddha along the east and west walls, whilst the band on the south wall has scenes depicting the royal family. Below this band is a border accentuated by calligraphy—white lettering against a black background. On the west wall, presiding over the Lhakhang, is the figure of Vajradhara with Shakyamuni in the varadha mudra (bestowing) painted on the east wall (opposite to Vajradhara) with the five Tathagata Buddhas. The space where the other two Tathagatas may have been represented has been painted over with images of Avalokitesvara and Padma Karpo, probably after the area was damaged due to water seepage. On the south wall are painted the goddesses Green Tara and a White Tara with Vajrasattva in the centre.

Unlike the paintings at Alchi, where the entire decorative scheme is part of an elaborate esoteric ritual, at Chamba Lhakhang the purpose of the painting is to create a sense of reverence and awe for the believers. The colours are bright and rich even after almost 500 years since the paintings were created, indicative of the quality of pigments used and the refinement in the application technique. Gold leaf and gold paint have been used liberally but aesthetically in paintings described as among the best in the region (Fig. 13b). In stark contrast to this extravagant display, to assert the importance of the Kagyupa sect and to memorialise the success of Tsewang Namgyal, the other two temples are individualistic and cloistered.

Fig 13b: Attendant Avalokitesvara of Chamba Lhakhang, with Guru Padmasambhava and Mila ras pa on the adjoining section of the wall. (Photo Courtesy: Sanjay Dhar)

II. Cham Chung

The similarity to a Central Asian mosque of the small temple of Queen Gyal Khatun is deceptive. Once inside, it is hard to imagine or associate the structure with a ‘mosque’. The walls are covered with some of the fiercest of wrathful deities, a shift from the peaceful and quiet iconographic programme in both the Chamba Lhakhang and the Serzang.

A painted stucco sculpture of the future Buddha Maitreya—fondly referred to as the ‘gentle small one’ in comparison to the monumental statues in the other two temples—is depicted seated on a platform, slightly off-centre, seated in padmasana (cross-legged) with hands in the dharmachakrapravartana (setting the wheels of dharma in motion) mudra.

There is a disagreement about the date and patron of this temple, as discussed in the historical overview section. However, the temple was certainly built between the date of accession of Jamyang Namgyal in 1600 and Senge Namgyal’s death in 1642. Therefore, it is difficult to discern if the temple was consecrated in or after 1642. As one enters, the calm visage of Maitreya stands in contrast to the red prabhamandala (aura) of the fierce deities on the east and west walls (Fig. 14a).

Shakyamuni with the 16 Arhats (elders—Buddhist saints) and his disciples (on the back wall) is depicted presiding over the chapel of fierce deities. A badly damaged Vajradhara, with exceptionally detailed drapery and finely executed attendants, sits next to the Shakyamuni. All the fierce deities—Yamantaka, Chakrasamvara and the six-armed Mahakala—are fine in proportion and execution (Fig. 14b).

III. Chamba Serzang

The Serzang, with its large metal-cased Maitreya, is the realisation of Jamyang Namgyal’s wish carried out by his wife, Gyal Khatun, and son, Senge Namgyal, around c.1624. The seated figure is approximately 6m tall. Though often referred to as the tallest sculpture, the Maitreya in the upper Lhakhang is taller. However, the metal casing of gilded copper along with its historical linkages to Senge Namgyal, Gyal Khatun and Jamyang Namgyal make it one of the most iconic images in Ladakh. The quality of metal work is very good. The sheets of beaten copper follow the complex contours of the clay figure, almost like skin. Its jewellery is expressed in the repoussé and encrusted with semi-precious stones. An elaborate crown is studded with semi-precious stones and the use of lapis lazuli is predominant.

The Lhakhang has rich paintings with judicious use of gold. The horizontal space is marked by a band of fabric motif on the top and a plain broad band on the lower side. The vertical space is divided into eight sections, with one major figure seated on a throne and three associated figures placed on top in small roundels. The composition is restrained with emphasis on a cohesive and clear execution (Fig. 15).

Both the north and south walls have seated figures in a row, representing the Eight Medicine Buddhas on one side and Eight Bodhisattvas on the other. The Kagyupa lineage teachers are represented on the walls flanking Maitreya. The wall on the east side has an arrangement of fierce deities along with the protectors of the cardinal directions. The iconographic programme in the Lhakhang and the architecture suggests an intimate and private space for the use of the royal family.

The first floor also has paintings, but these are mostly damaged and only faint remains survive today. There is a large space designed for an inscription, which seems to have been wiped out. Faint remains of a map of Basgo survive on one of the walls.

Endnotes

[1] Alternate spellings include Bazgo, Bab-sgo and Ba-mgo: (Francke 1925:284). The official spelling is Bazgoo. Wylie spellings are given at the first instance of the appearance of Tibetan names.

[2] The main source for the history of Ladakh is La-dvags-rgayl-rabs or The Royal Chronicles of Ladakh. This and several other minor chronicles have been partly translated and compiled by A.H. Francke. Luciano Petech has corroborated the events and dates with other sources from India, China and Tibet to establish a chronology of the various kings. This article accepts the chronology of the Namgyal dynasty based on Petech’s important study The Kingdom of Ladakh, c.925 -1842 A.D. (Petech 1977:171).

[3] Interestingly, this is the only temple in the fort complex that does not have an image of Tsonkhapa, indicative of the influence of Stagsan Raspa.

[4] The battle at the end of the three-year siege is called the Battle of Basgo. The accepted dates are around 1650 (Francke 1925:115).

[5] The exact purpose of this construction is not very clear.

[6] Much of the original wood and stone were removed by locals for the purpose of construction. Part of the structure has now been restored by the Basgo Welfare Committee and now houses the famous Basgo library with the gold/silver and bronze ink Kangur manuscripts.

[7] Restored in 2009–10 by the Basgo Welfare Committee.

[8] Restored in 2003–06 by the Basgo Welfare Committee. The upper portion of the chorten was damaged to an extent that it was difficult to understand or redefine its original form. Therefore, the existing portions of the top were consolidated and no reconstruction was attempted.

[9] This was discovered during the restoration campaign in 2004.

[10] Snellgrove refers to this structure as ‘the Temple of Kalzang’ (Snellgrove & Skorupski 1979:97).

[11] See, for example, Amburiq Mosque, Baltistan.

[12] The structure was restored in the 1990s by the Basgo Welfare Committee. In some areas, such as the balcony, minor changes to the original design have been incorporated.

[13] The temple is the least damaged and has never had any major repairs, thus preserving the original technical history—a rarity in Ladakh.

[14] Arga is a technique that uses a locally available calcium source from the Tibetan region to form a lime mortar. Arga was used on the roof and floors of buildings in Tibet. However, few examples of its usage have also been recorded in Ladakh.

[15] Any scholar wanting to research the architecture and art of the region, particularly of the post 16th-century period, does not have access to even a small portion of the material from across the Tibetan Buddhist cultural area through publications or other such visual sources. Often, scholars rely on their own limited documentation, and try to use it as best as possible with uneven results. For a detailed discussion, see Luczanits (2003) and Jackson (2003), who have suggested an alternate approach to the some of the problems.

[16] This date is not an absolute.

[17] Luczanits 2005,73.

[18] Luczanits 2005, 87.

[19] Luczanits 2005,90.

[20] Alchi and Saspol today, for example, are managed by the Gelugpa sect, with their mother monastery established at Likir.

[21] It would appear that Giotto is referring to the condition of the structure. However, a reading of the section with the quote tells us that Giotto is a connoisseur with a good eye for artistic material and in all likelihood was referring to the paintings.

References

|

Jamspal, Lobzang. 1997. ‘The Five Royal Patrons and Three Maitreya Images in Basgo.’ In Recent Research on Ladakh 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Colloquium on Ladakh, Leh 1996. Edited by Henry Osmaston and Nawang Tsering, 139–56. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsi Das Publisher Pvt. Ltd. |

||||||||

|

Luczanits, Christian. 2003. ‘Art-historical Aspects of Dating Tibetan Art’. In Dating Tibetan Art; Essays on the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Chronology from the Lempertz Symposium. Edited by Ingrid Kreide-Damani, 25–58. Reichert: Wiesbaden, Cologne. Reichert.

|

||||||||

|

Petech, Luciano. 1977. The Kingdom of Ladakh: 950 -1842 A.D. Rome: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

|

||||||||

|

2005. ‘The Early Buddhist Heritage of Ladakh Reconsidered’. In Ladakhi Histories; Local and Regional Perspectives, Edited by John Bray, 65–96. Leiden: Brill. |

||||||||

|

Bue, Erberto Lo. 2007. ‘The Gu ru lha khang at Phyi dbang: A Mid-16th Century Temple in Central Ladakh’. In Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the IATS: The Western Himalayas; Essays on History, Literature, Archaeology and Art. Edited by Amy Heller and Giacomella Orofino, 175–96. Leiden: Brill.

|

||||||||

|

Dainelli, Giotto. 1933. Buddhists and Glaciers of Western Tibet. Translated by Angus Davidson. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd.

|

||||||||

|

Dhar, Sanjay. 2010. ‘Documentation and Emergency Treatment of Wall Paintings in the Chamba Lakhang (Maitreya Temple): Developing a Methodology to Conserve Mural Paintings in India’s Ladakh District.’ In Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China, June 28-July 3, 2004. Edited by Neville Agnew, 286–96. Los Angeles: GCI.

|

||||||||

|

Francke, A.H. 1914. Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part I, Personal Narrative. Archaeological Survey of India, New Imperial Series Vol L, edited by F.W. Thomas. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing Press.

|

||||||||

|

Francke, A.H. 1925. Antiquities of Indian Tibet, Part II, The Chronicles of Ladakh and Minor Chronicles; Text and Translations. Edited by F.W. Thomas. Archaeological Survey of India, New Imperial Series Vol L. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing Press. |

||||||||

|

Howard, N.F. 1989. The Development of the Fortresses of Ladakh c. 950 to c. 1650 AD, East and West Vol. 39, No. 1/4 (December 1989), 217 - 288. Rome: Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO).

|

||||||||

|

Jackson, David. 2003. ‘The Dating of Tibetan Painting Is Perfectly Possible—Though Not Always Exact.’ In Dating Tibetan Art; Essays on the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Chronology from the Lempertz Symposium. Edited by Ingrid Kreide-Damani, 91–112. Reichert: Wiesbaden, Cologne. |

||||||||

|

Petech, Luciano. 1999 (First Published in 1937-39). A Study of the Chronicles of Ladakh (Indian Tibet). Calcutta/Delhi: Low Price Publications.

|

||||||||

|

Roerich, George N. 1931. Trails to Inmost Asia; Five Years of Exploration with the Roerich Central Asian Expedition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

|

||||||||

|

Snellgrove, David L. and Tadeusz Skorupski. 1977. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, Vol I, Central Ladakh. Warminister: Aris & Phillips.

Internet Resources:

|