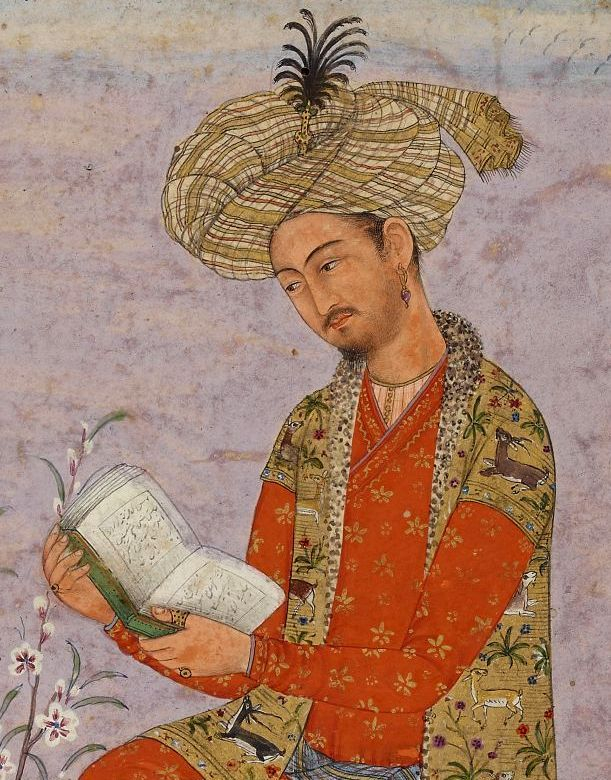

In Baburnama, the Mughal Emperor’s memoirs, Babur expresses his most intimate emotions, among which is the yearning for his homeland. Even in victory of the great land of Hindustan, Babur is lonely and desolate, as he expresses his pain through ghazals and rubais. Here, we present the vulnerable side of a powerful and controversial emperor. (Photo courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

In his memoir, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur writes of the time when seeing a melon from his Central Asian homeland brought tears to his eyes.[1] While it is difficult to imagine a Mughal emperor break down at the sight of fruit, Babur was not afraid of expressing his most intimate emotions. His memoirs, the Baburnama, is unparalleled in its candidness in the premodern Islamic world.[2] In it, Babur writes of the travails of being a king, of his grief at having lost his family, of his love for Kabul’s garden parties[3] and his infatuation for a 14-year-old boy, Baburi.

He also punctuates the political narrative with poetry that reveals his feelings with an unmatched frankness. When he sees Baburi in the Andijan Bazaar (modern-day Uzbekistan), he speaks of being ‘maddened’ and ‘afflicted’ and of walking ‘bare-hood, bare-foot, through street and lane’.[4] Expressing his desperation, he writes:

May no person be as ravaged, lovesick and humiliated as I.

May no beloved be as pitiless and unconcerned as thou.[5]

(Translations by Prof. Stephen F. Dale)

Babur wrote many such autobiographical poems, initially in Persian and then in Turki, which can be related to specific events in his life. Looking for literary merit, he wrote his compositions in the ghazal (poems of 6–15 lines)[6] and the rubai (poems of two lines or four half-lines)[7] forms—both considered the principal genres to express the ideal of courtly love in his Timurid world.[8]

Also read | The Jamas of Mughal India

Exiled and Alone

When he was just 12, Babur inherited Ferghana from his father. The same year, his base was attacked by his Timurid and Chagatai Mongol relatives.[9] Babur was thus forced to spend many years in exile. Constantly on the move, he longed for his homeland. He repeatedly tried to gain it back, but by 1501 he was left with no territory to call his own.[10] The next year, he took refuge from his Uzbek enemies with his uncle in Tashkent. Here, Babur wrote of his desolation:

No one cares for a man in peril.

No one gladdens the exile’s heart.

My heart has found no joy in this exiled state.Certainly no one takes joy from exile.[11]

Also read | Mughal Architecture: In Conversation with Ebba Koch

Here, Babur makes use of the standard poetry trope of ghurbat or exile, often used to refer to one’s separation from the beloved. Lending a twist to the form, he manages to adapt the conventional romantic emotion to describe how he felt as a refugee. Babur was also exiled multiple times during his lifetime. Sent away from Ferghana, Samarqand and his dear Kabul, the technique of using the ghurbat metaphor to describe his unfortunate circumstances marked most of his poetical career.[12]

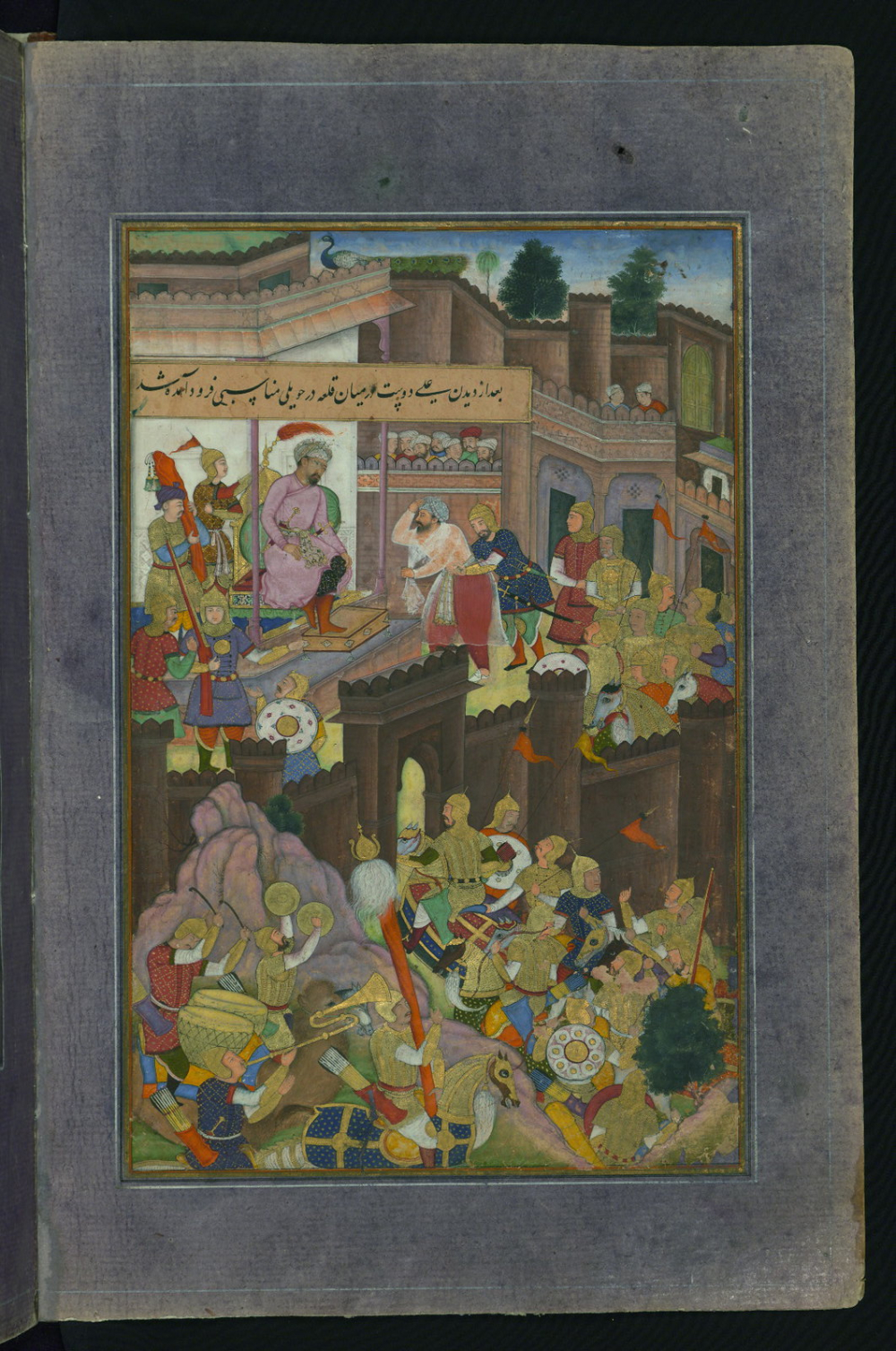

The Loss in Victory

In 1526, Babur’s luck glimmered when he conquered Hindustan from the Afghan ruler Ibrahim Lodhi. Although he finally had a territory to call his own, the victory could not shake off his feeling of alienation. If anything, being in an unfamiliar place only made him more homesick. During his days in Hindustan, as he longed for running water, melons and the sights of his homeland, poetry often became Babur’s refuge.

The emotion of alienation and isolation dominates what Prof. Stephen F. Dale, a leading scholar on Babur, has called Babur’s ‘Indian exile verses’.[13] It seems like Babur realised that even after winning Agra, Kabul was where his heart lay. He writes:

I deeply desired the riches of this Indian land.

What is the profit since this land enslaves me.

Left so far from you, Babur has not perished,

Excuse me my friend for this my insufficiency.[14]

The aggressive north Indian climate did not help alleviate Babur’s situation. He writes, ‘We were oppressed by three things in Hindustan: first by its heat, then by its strong wind and also by its dust.”[15] We get a sense of the misery he felt in the country’s hot and dusty weather when he contrasts Hindustan’s conditions with that of Kabul in this ghazal:

O those who left the country of India,

Talking about its misery and distress,

Remembering Kabul and its lovely climate

You ardently left India, that furnace.[16]

Babur’s companions also felt the same discomfort in the northern plains of Hindustan. Despite having scored another tough victory over Rana Sanga in the Battle of Kanwah in early 1527, many left for Afghanistan in May or June of the same year.[17] As a nomadic emperor, who had spent his life traversing tough terrains in dismal conditions, Babur must have become very close to his small group of men. When they deserted him in Hindustan, he clearly became distraught. By 1528, as Babur became older and lonelier, this distress had taken on shades of hopelessness:

Finally neither friends nor companions will be faithful.

Neither summer and winter nor companions will remain.

A hundred pities that precious life passes away.

O, alas, that this celebrated time is futile.[18]

With time, Babur’s health also started to deteriorate. In October 1527, he suffered a bout of dysentery. In 1530, he fell seriously ill once again, and died in the December of the same year. After being temporarily buried in Agra, he was put to rest according to his wishes, in Kabul. His simple tomb overlooking the scenery of one of his dearest cities was a sight he might have approved of.

When Babur inherited Ferghana from his father, his family was living in unfortunate circumstances.[19] But by the time of his death, he had done much to revive the glory of the Timurids. Foremost among them was laying the foundation of the Timurid-Mughal empire in India. However, this came at a cost. Pushed out of his homeland and exiled multiple times, Babur was forced to spend much of his life in unfamiliar places. Miles away from his beloved homeland, poetry, like for many of us, became his way to voice his inner feelings and perhaps seek refuge in memories of days past.

This article was also published on The Wire.

Notes

[1] Zahiuru’d-din Muhammad Babur, trans. Annette Susannah Beveridge, The Babur Nama (Everyman’s Library, 2020), 646.

[2] Stephen Frederick Dale, ‘Steppe Humanism: The Autobiographical Writings of Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur, 1483-1530’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1, (Feb., 1990), 37–38.

[3] Stephen Frederick Dale, The Garden of the Eight Paradises: Babur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483-1530) (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2004), 369.

[4] Zahiuru’d-din Muhammad Babur, The Baburnama in English (Memoirs of Babur): Translated from the Original Turki Text of Zahiuru’d-din Muhammad Babur Padshah Ghazi by Annette Susannah Beveridge: Volume 1 (London: Luzac and Co., 1922). Accessed January 26, 2021. https://archive.org/details/baburnamainengli01babuuoft/page/n7/mode/2up.

[5] Stephen Frederick Dale, The Garden of the Eight Paradises: Babur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483-1530) (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2004).

[6] Ibid., 497. The ghazal poems of 6-15 lines were written with rhyme aa, ba, ca for the half-lines of each line.

[7] Ibid., 497. The rubai poems of two lines or four half-lines were written with rhyme aaba for the half-lines of each line.

[8] Stephen F. Dale, ‘The Poetry and Autobiography of Babur-nama’, The Journal of Asian Studies 55, no. 3, (Aug., 1996), 642.

[9] Stephen Frederic Dale, Babur: Timurid Prince and Mughal Emperor, 1483-1530 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 2.

[10] Stephen Frederick Dale, The Garden of the Eight Paradises: Babur and the Culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483-1530) (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2004).

[11] Ibid., 268.

[12] Ibid., 269.

[13] Ibid., 339.

[14] Ibid., 431.

[15] Ibid., 366.

[16] Ibid., 353.

[17] Ibid., 352–53.

[18] Ibid., 433.

[19] Stephen Frederic Dale, ‘The Poetry and Autobiography of Babur-nama’, The Journal of Asian Studies 55, no. 3 (Aug 1996), 636.