‘Jama’ in Urdu means a garment, robe, gown or vest, basically an upper garment like a shirt. In Bangla, the shirt is referred to as ‘jama’ even today. The jama that this article explores is the long tunic-like dress with an upper bodice attached to the lower skirt at the waist. The length of the jama could be anywhere from just below the knees to almost heel-length; the fullness of the skirt and the length of the garment varied with time. The Platts Urdu dictionary describes jama and other words formed in conjunction with the jama thus:

جامه jāma

جامه jāma [S. यम, or यमल 'a pair'), s, m. A garment, robe, gown, vest; a long gown (having from eleven to thirty breadths of cloth in the skirt, which at the upper part is folded into innumerable plaits, and the body part, being double-breasted, is tied in two places on each side):—jāma-ḵẖāna, s.m. A wardrobe, a chest or sack for holding clothes;—jāma-dār, s.m. Keeper of a wardrobe; guard;—jāma-dār-ḵẖāna, s.m. =jāma-ḵẖāna:—jāma-dārī, s.f. Guarding;—s.m.f. The wardrobe-keepers, the guards:—jāma-dānī, s.f. A portmanteau, trunk (=jāmdānī).

Ain-i-Akbari, written by Abul Fazal Allami at the end of the 16th century, has a description of the jama worn by the people in those days (Allami 2014). It is also called takuchiya by Allami (Allami 2014). When the Mughals came to India, they came wearing Central Asian attire, which was similar to the jama, but Cohn writes that Rajputs took to wearing the jama before the advent of the Mughals in India. He does not differentiate between an angrakha and a jama (Cohn 1996). Books that deal with costumes in the northern part of India like The Costumes and Ornaments of Chamba write in detail about the jama, describing it as a dress worn by princes and courtiers. Jama was a full-sleeved garment worn crosswise above the waist to the right (Sharma and Sethi 1997).

When the English came to India in the 16th century, jama was the garment worn by men on the upper part of their bodies. It finds vivid descriptions in travellers’ diaries. From 1600 to 1900, the jama underwent many changes in its length, volume and variety. Since 1800, it began to be replaced by the angrakha but could never be wiped out as a fashion statement completely. A basic characteristic of the jama is that the upper bodice is normally full-sleeved. The garment is completely open and one side wraps over the other, crossing the centre front and is tied to the other side with strings. The lower part is like a wrap-around skirt and the upper bodice has a flap in front which could be worn in either the left or right direction, which is tied by strings. It is seen in most of the Mughal miniature paintings as the favoured article of men’s clothing. The styles of jama underwent changes with the passage of time. A belt known as a cummerbund or patka was tied at the waist on top of the jama. It was also known as katzeb. It was accompanied by loose or tight trousers or even a dhoti at times. For traveling out of the house or for public functions or occasions, a choga was worn over the jama. Depending on the season, either a heavy choga was worn over it or a light jacket (sometimes quilted) was worn. While describing the dress of the Dogras of Jammu, Raj Kumar notes that they wore a jama. He describes the jama as a frock coat with side fastening (Kumar 2006).

Jamas in the 17th century

Travellers’ diaries and line drawings, as well as the development of Mughal miniatures helps to give a timeline to the trends in fashion among upper class Indians. Edward Terry, who came to India in 1614 noted in his memoirs, A Voyage to East India, a garment like the jama which he called a habit, probably for the benefit of his readers. There is a picture of the fashions of India in Sir Thomas Roe’s journal, which also shows the garments worn in the same manner (Foster 1899). Terry does not use the word jama but it is clear that the garment that he has described in the passage is the jama. The ties with which the jama is fastened are referred to as ‘slips’. There were no buttons. Other than the jama he talks about another coat (an overcoat worn in winter months) which seems like a choga described by Chandramani Singh (Singh 1979). It could also be an Atma-sukh (see below). He wrote that this loose coat is made of ‘either quilted silk, or calico or of our English Broadcloth’. After having described the coats and overcoats, he wrote about a kind of undercoat (there is a mention of another shorter worn inside the jama) which may have been like an undershirt, which was probably the neemjama. It is mostly the obvious jama which Terry has written about below:

Now as the people of East-India are civil in their speeches, so are they civilly clad…..For the habits of this people, from the highest to the lowest, they are all made of the same fashion, which they never alter or change; their coats fitting close to their bodies unto their wastes (sic), then hanging down loose a little below their knees, the lower part of them fitting somewhat full; those close coats are fastened unto both their shoulders, with slips made of same cloth, which for the generality are made of coarser or finer white calico; and in like manner are they fastened to the waist, on both sides thereof, which coats coming double over their breasts, are fastened by like slips of cloth, that are put thick from their left arm-holes to their middle. The sleeves of those coats are made long, and somewhat close to their arms that they may ruffle especially from their elbows to their wrists. Under this coat they usually wear another slight one, made of same cloth but shorter than the other, and this is all they commonly wear on the upper part of their bodies. But some of the greater sort, in the cooler seasons of the day there, will slip on loose coats over the other, made either of quilted silk or calico or of our English scarlet broad cloth, for that is the colour they most love. (Terry 1777)

During winter months, a small quilted front-open vest was worn on top of the cotton jama for protection from the cold. This was called Sadri. It was popularised in the early 17th century by Emperor Jahangir (Bhushan 1958). There were other winter coverings like the quilted Choga called Atma-sukh (literally meaning pleasure or happiness of self/soul). This was like a long coat made of cotton in two layers with a layer of fine cotton fibre in between. It was stitched and quilted in the Rajasthani technique which is famous even today. This name of Atma-sukh was given to the garment by Akbar. Samples of Atma-sukh can be found in the museums at Jaipur and New Delhi (Singh 1979).

After the detail of the upper garments, Terry goes on to describe the lower garment, which unlike the English hose of the time period is a pyjama (spelt pajama too). ‘Py’ means leg and ‘jama’ means ‘cloth’ or ‘to clothe’, thus pyjama means a garment for the legs. He does not refer to it as pyjama but refers to them as ‘longer breeches’ and likens them to the ‘Irish Trowsers’. Even if they tapered towards the lower leg, they usually ballooned at the top. The construction of these pyjamas was done with a centre seam in front and back and an extra piece of gusset like fabric was added at the crotch for comfort in sitting. These were not fitted to the body but were loose garments and were secured at the top with a string which was inserted by folding the top/upper edge of the pyjama. The string ran through the entire width of the pyjama and could be pulled and tied in front, thus it did not make much difference if the wearer gained or lost a few pounds, as it was adjustable. It was important for the Indians to wear such loose garments as they were accustomed to sitting on the floor. The pyjamas were also referred to as Izars and the strings as izar-bandhs. The pyjamas ‘which come to their ankles, and ruffle on the small of their legs’ are referred to as Chooridar/Churidar Pyjamas (Singh 1979:157). These pyjamas can still be seen in India, they are worn by both men and women under the long tunics called kurtas. They are not cut on strait grain but cut on bias and stitched to give stretch ability to the fabric. This results in a lot of extra fabric which is used to create the ruffle on the small of the leg so that there is ease of wearing and air circulation. The appearance thus is of many rings or bangles (called chooris or churis in Hindi/Urdu) around the leg; the word churidar pyjama denotes the 'choori bearing pyjama'.

Although Terry described in detail the kind of clothes worn by the men in India, there is no reference to correct terminology that people in India used. For the benefit of his readers, he uses words like coats and trousers (trowsers). It is possible that he did not understand native languages and simply described what he saw:

Under their coats they have long breeches, like unto Irish trowsers, made usually of the same cloth, which come to their ankles, and ruffle on the small of their legs. For their feet, they keep them (as was before observed) always bare in their shoes.

Some of their grandees make their coats and breeches of striped taffeta of several colours, or of some other silk stuff of the same colour, or of slight cloth of silver or gold, all made in that country. But pure white and fine calico lawn (which they there make likewise) is for most part the height of all their bravery; the collars and some parts of their upper coats being set of with some neat stitching. (Terry 1777)

Terry’s observations and writings have been most invaluable not only in terms of the look or style of apparel but also for the details of the fabrics used to create such apparel. The use of silks, taffetas, cloth of silver and gold, calicos in Indian apparel has been highlighted by his writings. He used the word ‘grandees’, which probably here means the rich or the nobles, aristocrats of the society. The ‘grandees’, he wrote, use multi-coloured silk to make their garments and also use cloth made with gold and silver. He was probably talking of the Indian brocades here. These sound like the Banarasi silks which were used by the rich to make their clothes. In spite of the use of silk by the rich, the most common cloth seems to be cotton, woven as fine lawn. He refers to the stitching done on collars and some part of upper coats. The use of the word stitching here probably refers to embroidery done on the Chogas.

The surgeon, John Fryer, who came to India in 1673 also made similar observations (Fryer 1698). He noted that the Indians had a rich attire. His observations match those of Terry although there is a gap of nearly 60 years between the two accounts. Thus the kinds of clothes worn in the early and late 17th century are almost similar. Francois Bernier discussed at length the workshops in the Mughal empire known as Karkhanas for making clothes and other crafts (Bernier and Constable 1891). Francois Bernier also related in his memoirs that Jahangir ('Jehan-Guyre') ordered European clothing to be made for himself and for all his courtiers. The reason was that he wanted to turn Christian and thought that the tailors should be brought to India to turn their turbans into hats and their cloaks into coats. But when he himself tried that clothing he was not very happy with the result. Jahangir then passed it off as a joke (Bernier and Constable 1891).

While noting down the kind of footwear worn by the Indian men, Bernier does not call them slippers or Persian slippers but referred to them as shoes. He noted his observation of bare feet. He also mentioned that he has observed even earlier that men keep their feet bare inside the shoes (Persian slippers), called jooties, or jutis in India. As observed by Edward Terry Fryer too , the Indians did not wear shoes or stockings in the British style, but wore their embroidered slippers. Fryer noted that there were carpets on the floor and that people sat square legged on the floor. He observed that it was not considered a good habit to let your legs hang while sitting. According to him, the Indians believed that legs or feet should not be seen while sitting, someone whose legs and feet are seen while sitting was considered ill-bred among Indians (Fryer 1698). The fact about people sitting on the floor has also been written by Sir Thomas Roe, who had to request for chairs as he could not stoop probably due to his tailored clothing (Foster 1899).

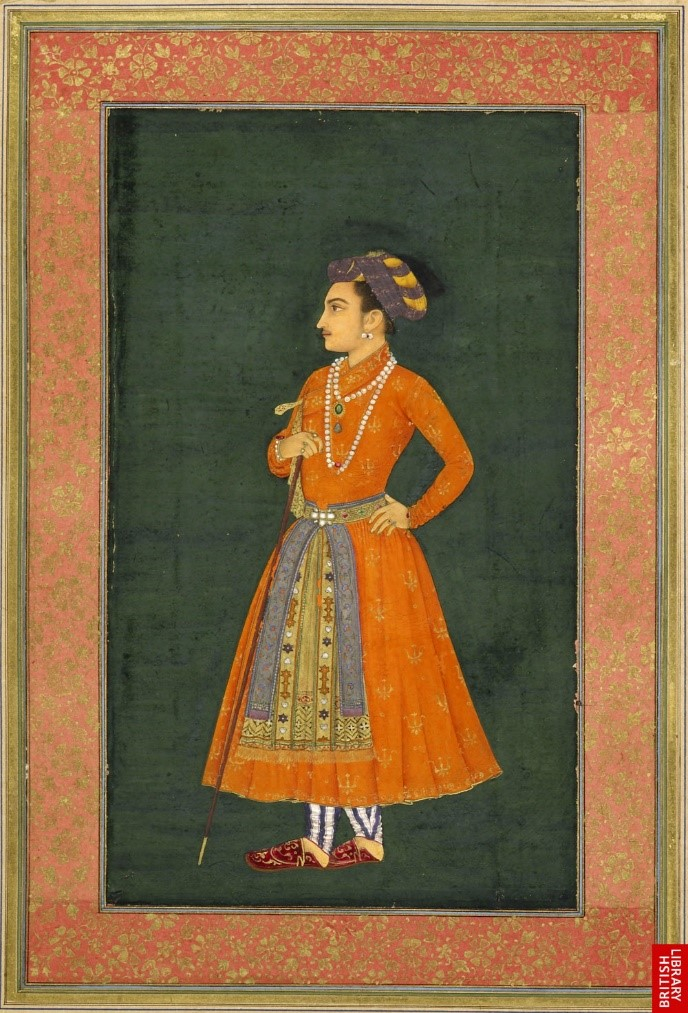

This dress of the elite Indian men as described by these travellers finds expression in the painting of Dara Shikoh, who was a Mughal Prince, the son of Shah Jahan. This painting from the 17th century is part of British Library collection of Indian Miniatures. It shows him wearing a jama of printed fabric. The print appears to be gold foil printing on an orange background. He wears a striped pyjama underneath. There is a cummerbandh tied on his waist with jewels. This painting and other Mughal miniatures (see images of the jama in the 17th century), show the type of jama that was worn in the 17th century. The Padshahnama, written during the reign of Shahjahan contains a wealth of miniature paintings that show the styles of the jama of 17th century (Altavista.org).

Figure 1.1 Mughal Prince Dara Shikoh 1631–37

Courtesy: Online database of British Library; the image was first seen at the Exhibition of Mughal Miniatures by British Library in April 2013.

Jamas in the 18th century

During the 18th century too, the fashion statements of the elite continued to remain similar. Jamas and pyjamas remained in fashion, but the construction began to alter. The images show that the jamas became longer and almost touched the feet. These garments remained in fashion and were worn by the aristocrats irrespective of their religion. This fact has been noted by Fredrick John Shore, the judge who wore Indian clothes and had a great understanding of India and her people. According to him, the only difference was that the Hindus tied theirs to the left whereas the Muslims tied theirs to the right (Shore 1837). Other than that, the fabric, cut and construction of the formal garments remained same (Watson 1866). This was in contrast to the changing fashions of the West. In India, there was more stability in terms of clothes despite political turbulence of the 18th century; although the power of the Mughal Empire was on the decline, the elite still considered the Mughals and their fashions supreme. A variety of Rajasthani and Pahari miniature paintings of the mid–18th century show the costumes worn by Indians at that time. In general, they consist of the Mughal costumes as elaborated above, or they consisted of the simple unstitched type of garments worn by the Hindus. The fact is that even by the end of the century from north to south, and east to west in India, the aristocracy continued to wear Mughal-style garments, which continued well into the 19th century (Watson 1866).

Jamas in the 19th century

During 19th century, Lucknow became the centre of fashion with the weakening of Mughal Empire. Although in general the dressing of the elite of India continued to be in the style of the Mughals, there is the curious case of the Nawabs of Lucknow (or Oudh) in the early 19th century. Ghazi-ud-din Haider, who ascended the throne in 1814, decided to change his title from that of a nawab to a king. A famous painting by Robert Hume done in 1820, at present in Victoria Memorial at Calcutta, shows him in a fur-lined robe like the European kings and instead of the turban or pugari, he wears a crown. This shows the beginnings of change in royal insignia. The Mughals no longer carried the political strength that the British had established. As a result, the nawabs of Lucknow, who had sold their seat to the British, and were puppet rulers, still wanted to convey power by the adoption of European garments. From 1814 to 1847, there were four self-proclaimed kings in Lucknow, who have been represented in paintings wearing European royal insignia.

Although long and heavy jamas continued well into the 19th century, a new garment called the angrakha began to appear which was different from the jama and began to use buttons along with tie-up strings. The corrupted form of button was called bootam in Hindustani (Gilchrist and Williamson 1825). In fact, Indians began adopting the concept of buttons, and the small fabric buttons that can be seen in European fashions in the 17th and 18th centuries now began to be used in India as well. They were called ‘ghundis’ and were being used in place of tying.

Some jamas from the 19th century can be seen in the Calico Museum, Ahmedabad. The book on the museum's collections (Goswamy 1993), has visuals and patterns of the jamas. These are very useful for the student of dress history as they show the images and construction of the jamas in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

References

Allami, A.F. 2014. The Ain-I-Akbari. Delhi: Low Price Publications.

Altavista.org. Illustrations from the 1636 Padshahnama of Shah Jahan showing Moghul Soldier & Civilian Costume.Online at http://www.warfare.altervista.org/Moghul/ShahJahan/Padshahnama.htm.(viewed on September 27, 2016).

Bernier, F. and A. Constable .1916. Travels in the Mogul Empire AD 1656–1668. London: Oxford University Press.

Bhushan, J. B. 1958. The Costumes and Textiles of India. Bombay:Taraporevala's Treasurehouse of Books.

Cohn, B.S. 1996. Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Foster, W. 1631. The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mogul, 1615–1619, as narrated in his journal and correspondence. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society.

Fryer, J. 1698. A New Account of East-India and Persia in Eight Letters: Being Nine Years Travels begun 1672 and finished 1681: Containing observations made of the Moral, Natural and Artifical Estate of Those Countries, London: Printed by R.R. for Ri Chiswell.

Goswamy, B.N. 1993. Indian Costumes in the Collection of the Calico Museum of Textiles. Ahmedabad: D.S Mehta on behalf of Calico Museum of Textiles.

Kumar, R. 2006. Paintings and Lifestyles of Jammu Region: From 17th to 19th Century A.D. New Delhi: Kalpaz Publications.

Sharma, K.P. and S.M. Sethi. 1997. Costumes and Ornaments of Chamba. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company.

Shore, F.J. 1837. Notes on Indian Affairs. London: J.W. Parker.

Singh, C. 1979. Textiles and Costumes from the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum. Jaipur: Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust.

Terry, E. 1777. A Voyage to East-India. Salisbury: W. Cater, S. Hayes, J. Wilkie, and E. Easton.

Watson, J.F. 1866. The Textile Manufacturers and the Costumes of the People of India. London: The India Office.