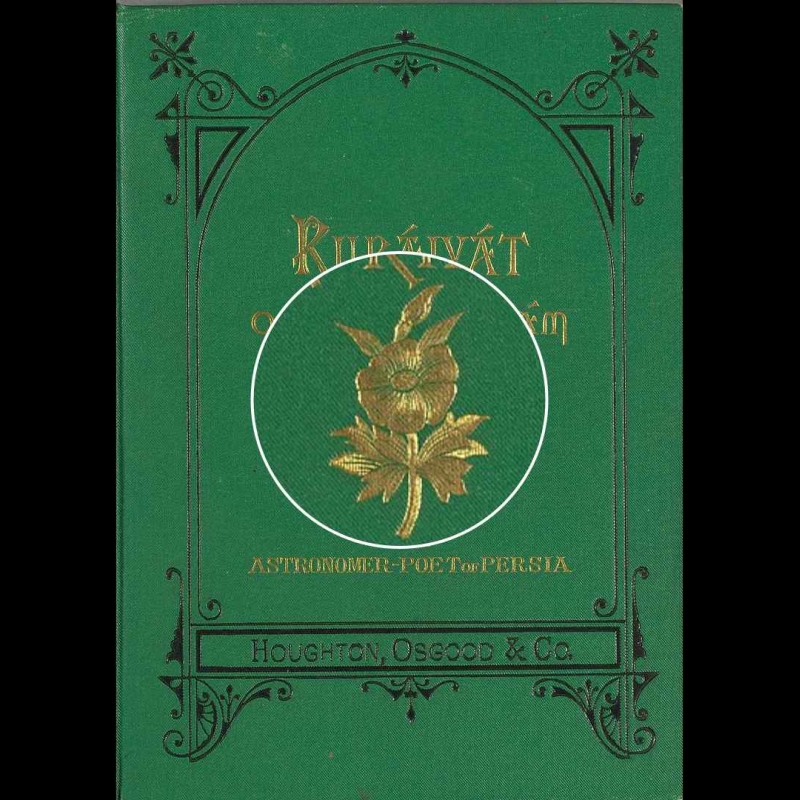

During a trip to the Salarjung Museum in Hyderabad, Prof. B.N. Goswamy was shown a most sumptuous-looking edition of one of the great classics of English literature—even if it is essentially a translation—Edward FitzGerald’s rendering of the ‘Rubai’yat of Omar Khayyam’. Here he writes about how FitzGerald’s love affair as it were with Omar Khayyam’s work. (In pic: The book cover of 'The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the astronomer-poet of Persia'. First American edition: Boston, Houghton, Osgood and Company, 1878. From the third edition of the English translation by Edward FitzGerald; Photo courtesy: Houghton Library/Public Domain)

This article appeared originally in The Tribune, Chandigarh and is reproduced here with permission.

My translation will interest you from its form, and also in many respects in its detail: very un-literal as it is. Many quatrains are mashed together: and something lost, I doubt, of Omar’s simplicity, which is so much a virtue in him . . . I suppose very few People have ever taken such Pains in Translation as I have: though certainly not to be literal. But at all Cost, a Thing must live: with a transfusion of one’s own worse Life if one can’t retain the Original’s better. Better a live Sparrow than a stuffed Eagle”. — Edward FitzGerald to E.B. Cowell, 1859

Not more than a few short weeks back, I was walking through the corridors of the sprawling Salarjung Museum in Hyderabad, when the Director of the Museum, Dr. Nagendra Reddy, who was kindly taking me around, gently directed me to the Library of the Museum. I had been to the Museum on my earlier visits to that city, but never seen the Library. It was some kind of a revelation, for it felt as if one had walked back into time: the Library was, like thousands of antiques and other objects that the Museum houses, something that Sir Salar Jung III, former Prime Minister of the state of Hyderabad, after whom the Museum is named, had personally owned once. Shelf after shelf filled the space, books on the most diverse of subjects, including evidently some rare or precious volumes, jostling one another. Dr. Reddy asked an assistant to pull out one of these: a most sumptuous looking edition of one of the great classics of English literature—even if it is essentially a translation—Edward FitzGerald’s rendering of the Rubai’yat of Omar Khayyam.

Also read | Why Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam is One of the Most Controversial Translations Ever

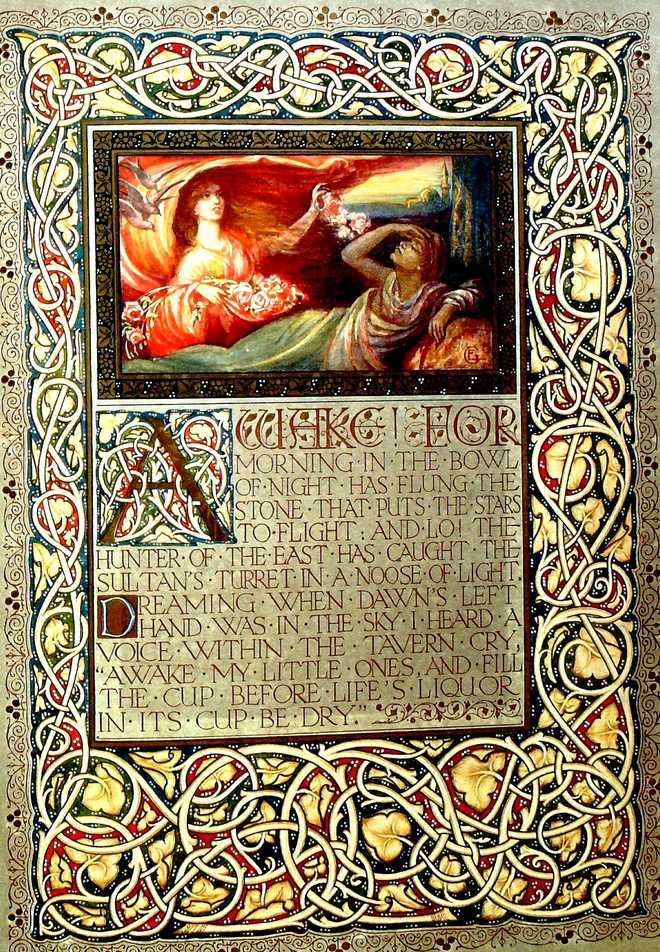

Even as I began to turn, gingerly, the pages of that exquisitely bound and printed volume that dated back a hundred years and more, the verses, read long ago but embedded in my memory, started to surface in the mind: “Awake! For Morning in the Bowl of Night/ has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to flight . . . . ”; “The Moving Finger writes, and, having writ, moves on . . . ” and so on. Page after illuminated page here embellished the verses: cursive calligraphy, arabesque ornamentation, the occasional image, all adding to the aesthetic impact. I decided right then in my mind to research the names of the printers and binders of the book, as also to tie down some facts and dates relating to Omar Khayyam and FitzGerald. Some I knew, but others needed to be confirmed.

First, however, about the printers and binders, in their times called “the Rolls Royce of Book-binding”, about whom I knew nothing till now. Sangorski and Sutcliffe: two men, both English, who took up, at the turn of the century, the art of book-binding of the kind that prevailed in the Middle Ages. Jewelled bindings, using metalwork, semi-precious stones, ivory, and rich fabrics, is what they began to specialize in, creating a sensation in the publishing world. Some of the finest books to be produced at that time were made by them, each a masterly creation in its own right. The volume in the Salarjung library, with its glistening peacock motif on the cover, owed itself to them.

Also read | Bangla Qawwali: Sufi Musical Tradition of Bengal

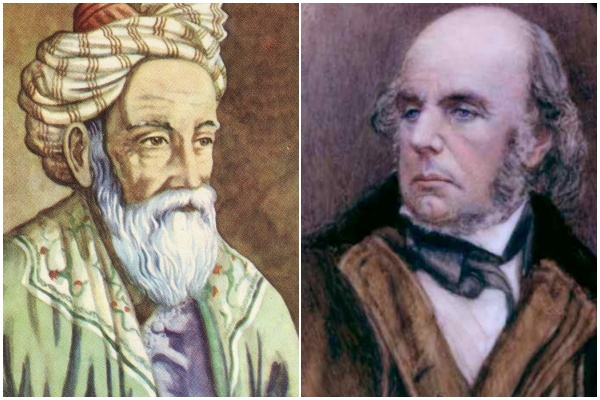

Omar Khayyam, as one knew of course, was born in Nishapur in Iran, in 1048. He came from a family of ‘tent-makers’—khayyams, makers of khaimas—but turned, unexpectedly, into a scholar, writing learned treatises on algebra, geometry, astronomy and philosophy. His name, however, has survived most as the author of the Rubai’yat—quatrains, that is four-line verses—that were a well-established form in Persian poetry. It was not until 1461, however, that someone created an exquisite little hand-written volume of the Rubai’yat with 158 of Omar’s poems. That volume, naturally in Persian, was purchased several centuries later by Sir William Ouseley (1769–1842), a collector of manuscripts, who then left it along with many other items to the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

In 1856, a scholar named Edward Cowell (1826–1903) chanced upon this book. Cowell had taught himself Persian and other languages at a very young age and he showed the book to his friend, Edward FitzGerald (1809–1883), whom he had been persuading to learn Persian. FitzGerald came from a well-placed family and had friends in the literary world of the times which included Thackeray, Tennyson and Carlisle. Himself, he wrote some poetry and prose but was most at home in translation work. The newly-learnt Persian now came into play when he was introduced to Omar Khayyam’s rubai’yat. A love affair as it were with Omar Khayyam’s work developed. He could not tear himself away from those ruba’is: simple as they were but marked by such ‘profound emotion and wistful melancholy’. However, it was no literal translation of the Persian verses that he was after—he called his work ‘transmogrification’, change in appearance or form in other words; his endeavour was to create ‘a thing that must live’.

Even though FitzGerarld’s work has run into hundreds of editions and reprints since then, it is of interest that the first edition, published in 1859 by Bernard Quaritch, consisted only of 250 copies. Of these the poet took 40 himself; the rest remained with the publisher who had priced them 1 shilling a piece. Almost nothing sold, however; two years later the price was reduced to 1 pence, and the books were put outside the publisher’s shop in a bin. Someone, it has been recorded, bought a copy at that price and presented it to Dante Gabriel Rossetti—poet and painter, so much a part of the Art Nouveau movement—who picked up some more and shared them with some icons of the art world, among them Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris, Richard Burton, and John Ruskin. Thomas Hardy and T.S. Eliot were to follow. Soon nearly everyone knew and could recite: “Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough/A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse — and Thou.”

A footnote: Speaking of Omar Khayyam, I do not know how many are aware of the translation in Urdu of his rubai’s by poet Naresh Kumar Shaad. Verses like:

Hui jo shaam to bolaa woh peer-i maikhana

arrey, woh rind kahaan hai saboo ka diwaana?

Bulaao jaldi se usko keh uska jaam bharein

mabaada maut na bhar daaley uska paimaana.

This article has been republished as part of an ongoing series Art N Soul from The Tribune.