Edward FitzGerald’s translation of Khayyam’s verses as the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam has been published in over 2000 editions and translated into more than 70 languages. However, in the process, FitzGerald not only transcreated Khayyam’s poetry but his identity as well, turning the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam into one of the most controversial works of translations. (Photo Courtesy: Library of Congress [Public Domain])

On September 2, 1863, English art critic John Ruskin wrote a letter to the unknown translator of the poetry of Omar Khayyam (1048–1123)—an astronomer and mathematician from Persia—saying, ‘I do with all my soul pray you to find and translate some more of Omar Khayyam for us: I never did – till this day – read anything so glorious, to my mind as this poem.’ He concluded the letter with the words ‘More – more – please more.’[i] The translator—Edward FitzGerald—did not read the letter until 1872. By that time, the third edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam (a collection of rubái or quatrains) had been published, and Khayyam had taken the Western literary world by storm.

FitzGerald’s translation of Khayyam’s poetry first appeared in 1859. However, interest in the book started to build only after it was discovered in the 1860s (being sold at a princely sum of one penny a piece) by the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who popularised it amongst the pre-Raphaelites (a group of English painters, poets and critics).

75 years after its initial publication, in 1934, a copy of the Rubáiyát in its original wrapper was sold for $9,000.[ii]

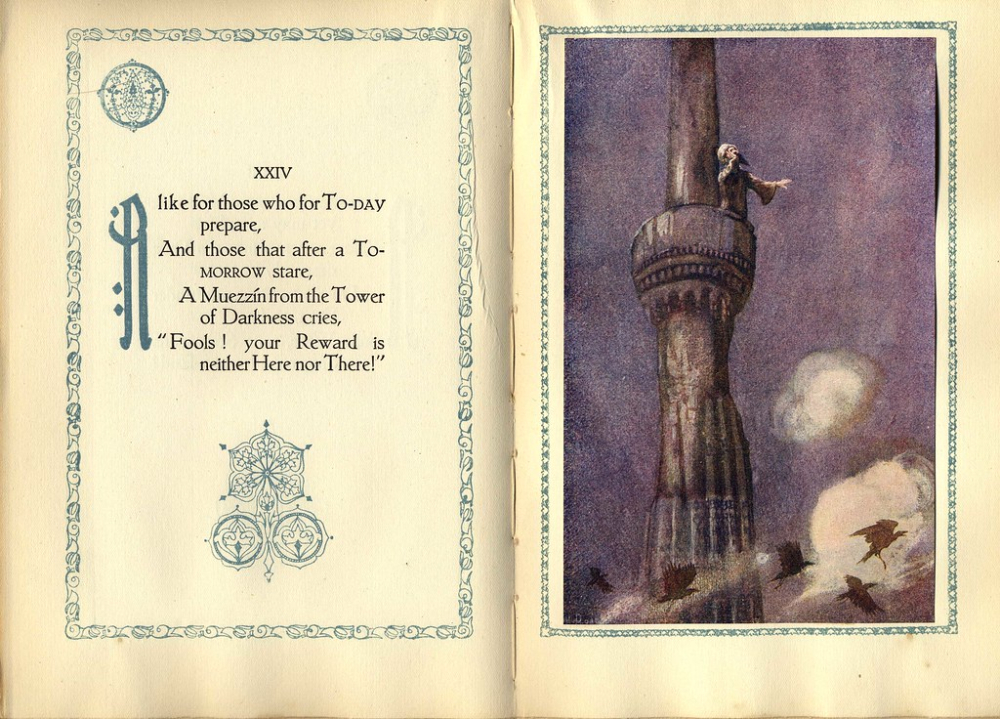

The Rubáiyát has been published in over 2000 editions, translated into more than 70 languages (from Japanese to Swahili) by almost 800 publishers, and illustrated by over 220 artists worldwide (In pic:Spread from an early 20th century printing of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Illustrations by Willy Pogany; Courtesy: William Creswell/Flickr)

The Wandering Quatrains

In the book’s Introduction, FitzGerald opines, ‘Omar [Khayyam]…has never been popular in his own country, and therefore has been but scantily transmitted abroad’.[iii] There could be some truth to this, as it took around 700 years for the first translation of his quatrains—in German, by German Orientalists—to appear. It was only in the 19th century that the discovery of FitzGerald’s English translations transformed him from a relatively unknown figure in the world of poetry to a global phenomenon.

Today, Khayyam is one of the most prolific Persian poets, and Rubáiyát is one of the most famous works of poetry. The Rubáiyát has been published in over 2000 editions, translated into more than 70 languages (from Japanese to Swahili) by almost 800 publishers, and illustrated by over 220 artists worldwide.[iv] While these are impressive numbers, many scholars—especially from Iran—have questioned the authenticity of FitzGerald’s translation, insisting that many quatrains were misattributed to Khayyam.

The Rubáiyát of Fitz-Omar

Shedding light on the birth of ‘Fitz-Omar’, Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote that ‘the two [Khayyam and FitzGerald] were quite different, and perhaps in life might not have been friends; death and vicissitudes and time led one to know the other and make them into a single poet’.[v] Scholars and writers view FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát simply as English poetry with Persian allusions, and it is widely accepted that his English quatrains are loose translations based on Khayyam’s original verses. In fact, FitzGerald himself called the translation ‘very un-literal’, but ‘at all cost, a thing must live…Better a live sparrow than a stuffed eagle’. He called his transcreation of Khayyam’s verses, ‘transmogrification’. In what is called the 67th Bodleian quatrain, Khayyam had written:

Roz-ast khush o hava nah garam ast na sard

Abr az rukh gulzar hami shawid garad

Bulbul ba-zaban pahalawi ba gul zard

Fariyad hameen zind kah mein baawad khurd

The quatrain was transcreated by FitzGerald as:

And David’s Lips are lock’t; but in divine

High piping Pehlevi, with “Wine! Wine! Wine!

‘Red Wine!’—the Nightingale cries to the Rose

That yellow Cheek of her’s to incarnadine

While there have been many controversial cases of transcreation, FitzGerald’s work raised many questions, primarily because he was accused of attributing verses Khayyam never wrote to the Rubáiyát. Of the 1,400-odd quatrains attributed to Khayyam, some scholars estimate only 200 are his, while others such as Ali Dashti (author of In Search of Omar Khayyam and an authority on the works of the Khayyam) say that ‘only 36 quatrains have a likelihood of authenticity’.[vi] In the introduction to the Rubáiyát, Daniel Karlin notes that ‘the structure of the poem, in one sense, “translates” nothing, because it has no counterpart in the original text.’[vii] Despite the contention, FitzGerald's Rubáiyát not only gained immense recognition but also established Khayyam as a freethinking and hedonistic poet.[viii]

Rather than the ‘carpe diem philosophy’ professed in FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát, the original Persian verses offer a pessimistic view of the world and the Sisyphean situation humans are stuck in (Courtesy: Omar Khayyam (May 18, 1048–December 4, 1131) [Public domain])

Who was Omar Khayyam?

Khayyam died in the 12th century CE as a Persian astronomer and mathematician, and was ‘reborn' as a poet in the 19th century to fulfil, in the words of Borges, ‘the literary destiny that had been suppressed by mathematics in Nishapur [in the Persian province of Khorasan]’. FitzGerald not only transformed Khayyam’s poetry through his translations, but his identity as well, portraying him as an ‘anti-Sufi, a hedonist and atheist’.[ix] This was the image that went on to influence writers such as the Irish poet Oscar Wilde, who described the Rubáiyát as ‘a masterpiece of art’.

However, rather than the ‘carpe diem philosophy’ professed in FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát, the original Persian verses offer a pessimistic view of the world and the Sisyphean situation humans are stuck in. In Khayyam’s quatrains, the world is a ‘salt-desert, a nest of sorrow, a station on the road’, while in FitzGerald’s transcreation it becomes more about ‘make the most of what we yet may spend’.[x]

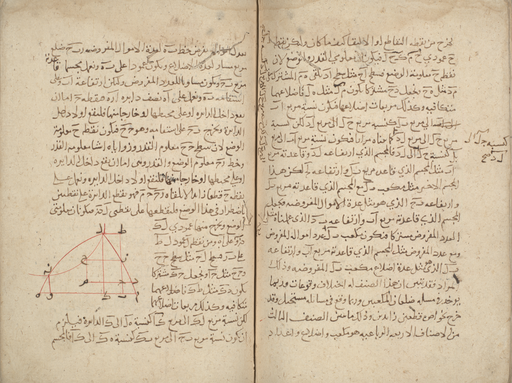

Khayyam died in the 12th century CE as a Persian astronomer and mathematician, and was ‘reborn' as a poet in the 19th century to fulfil, in the words of Borges, ‘the literary destiny that had been suppressed by mathematics in Nishapur' (Courtesy: Man vyi [Public domain])

To make amends, acclaimed English poet and critic Robert Graves and Sufi writer Omar Ali-Shah re-translated Khayyam’s verses. Graves heavily criticised FitzGerald’s translations in the preface of his collection titled ‘The Fitz-Omar Cult’. However, the irony would hit hard, as after the publication of his collection, Graves eventually—and agonisingly—came to realise that his translation of Khayyam’s poetry was nothing but a translation of scholar Edward Heron-Allen’s Persian version of FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat.

This episode not only sums up why Khayyam’s verses are one of the most controversial and debated translations in the West even today, but also, perhaps, lends some truth to the Italian saying traduttori traditori—translators [are] traitors.

This article was also published on Scroll.in.

Notes

[i] Edward Fitzgerald, The Letters of Edward Fitzgerald, Volume 3: 1867–1876., eds. Alfred McKinley Terhune and Anabelle Burdick Terhune (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 416.

[ii] Esmail Zare-Behtash, ‘FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát: A Victorian Invention’ (PhD thesis, Department of English, Australian National University, 1994), 186.

[iii] Edward FitzGerald, Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1859).

[iv] William H. Martin and Sandra Mason, The Art of Omar Khayyam: Illustrating FitzGerald's Rubaiyat (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2007).

[v] Jorges Luis Borges, Other Inquisitions (1937–1952) (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975).

[vi] William H. Martin and Sandra Mason, The Art of Omar Khayyam: Illustrating FitzGerald's Rubaiyat (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2007).

[vii] Padma Rangarajan, Imperial Babel: Translation, Exoticism, and the Long Nineteenth Century (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014), 123.

[viii] Roman Krznaric, ‘How “The Rubáiyát Of Omar Khayyám” Inspired Victorian Hedonists,’ 2017, https://iranian.com/2017/06/05/how-the-rubaiyat-of-omar-khayyam-inspired-victorian-hedonists/ (last accessed on July 9, 2019).