Profile by a Long-Time Associate

'Dear Sasi,

Enclosed is the air ticket [for Smita Patil]. But I forgot something. I should have taken an executive-class ticket for Smita. Kindly ask her to convert it to executive-class while travelling. I can reimburse her when in Madras. Since very few people travel in executive-class, she can easily get it done,' Aravindan wrote in his letter in Malayalam on February 15, 1985.

Aravindan used to communicate with his friends and close associates through inland letters and postal envelopes. He is known more for his long silences, rather than for his oratory or communicative skills. Most of his letters contained not just personal or work-related information, but also his thoughts on his work and his anxieties regarding the socio-political events that occurred between 1975 and 1984.

His letters reveal much about his creative life and his agonies and concerns as a film-maker. Even before his film-making career, he made his mark on the socio-cultural consciousness of Kerala by publishing a weekly cartoon series in the prestigious weekly, Mathrubhumi, edited by the iconic writer, MT Vasudevan Nair. The cartoon series, which was titled Cheriya Manushaynum, Valia Lokavum (Small Men and Big World), featured his path-breaking commentary on the social milieu in the late 60s and 70s in Kerala. The series made Aravindan a part of Malayali social and cultural discourse, long before he became a world-renowned film-maker.

During his stint at the National Rubber Board at Kozhikode in northern Kerala, where Mathrubhumi was also headquartered, Aravindan became a key member of the literary and social network in the town. His close friends were writers, theatre personalities, musicians, and film-society enthusiasts. His counted amongst his friends MV Devan (painter), MT Vasudevan Nair (writer turned film-maker), Thikkodiyan (writer and script-writer of his first film), Pattathuvila Karunakaran (producer of his first film), and KA Kodungalloor (a writer).

Aravindan drew inspiration for his cartoon column, Cheriya Manushyarum Valiyalokavum, from conversations with his friends, often at evening gatherings which would last till midnight. In fact, some of the characters in the cartoons are based on his friends. Looking back at his first forays into cinema, which received support and funding from this circle of friends at Kozhikode, we can see that the composition of sequences and the characters in his cartoons are mirrored in many of his films. Further, the content of the films he made carried the satire and dry humour of his cartoons. He retained his cartoonist self, even when he turned to film, and nourished it with a deeply humane and philosophical perspective, as seen in his first film Uttarayanam (Throne of Capricorn), which can be seen as an extension of the stories of his cartoon characters—Ramu and Guruji. The local success of Uttarayanam points to the warm welcome that Ramu and Guruji received, especially among young people. Incidentally, Aravindan’s son, a graduate from the National Institute of Design, is named as Ramu, and the director himself is nicknamed 'Guruji', by his younger friends.

In 1975, after the release of Utharayanam, Aravindan was transferred to Thiruvananthapuram by the Rubber Board. There, Chitralekha Film Society was in the process of greenlighting a new series of Malayalam films under Adoor Gopalakrishnan, an admirer of Aravindan’s cartoon series in Mathrubhumi. It was here that Aravindan really became a part of the New Cinema Movement in Kerala, giving the state a place on the global map of cinema.

Aravindan’s first film was planned to be executed by Adoor’s first film’s crew and even used Chitralekha Film Cooperative’s equipment, as the director was new to the medium of films. Aravindan was to be the art director of Adoor’s first film project, Kamini, which never saw the light of day. Even so, they were the best of friends at that time, and they were willing to work together in every way. When Uttarayanam received a special award during the film awards given in the 25th year of India’s Independence, little did the audience know that Adoor Gopalakrishnan was in the national jury which chose the film.

Soon after bagging the national award, Aravindan felt that he needed an academically-trained team to execute his projects, as expectations were sky-high, now. It was at this juncture that Aravindan assembled a team comprising FTII-trained Shaji N Karum (cinematographer) and Devdas (sound recordist), alongside his existing team of writers and cultural activists. Being the son of satirist and humour writer MN Govindan, he was well-known amongst Kottayam-based cultural activists and writers, as well as his own circle of Kozhikode-based Malabar cultural activists. His network, which included dramatists such as CN Sreekantan Nair, was also well-known. With the help of Malabar-based modernist Malayalam writers, Aravindan was ready to make his own path in Malayalam films.

It was in Thiruvananthapuram that he chanced upon a producer of family films—Raveendran Nair—popularly known as Ravi. He also happened to be a cashew exporter, and a man of fine sensibilities. Ravi would go on to produce several iconic films for both Aravindan and Adoor Gopalakrishnan, raising the new generation of Malayalam films to a global level. Aravindan’s first film was produced by Pattathuvila Karunakaran, a short-fiction writer from Kozhikode. Adoor’s first film was produced by Chitralekha Film Co-operative, with funding from Film Finance Corporation of India (FFC).

The entry of Ravi—the gentleman producer—gave a new impetus for creative film-making in Kerala. The best films by these iconic directors were produced by Ravi. If it were not for him, Aravindan could never have made a film like Kanchana Sita, his second film. Ravi gave him complete creative freedom, thus giving Aravindan the freedom to explore multiple possibilities and experiment with the medium. This enabled him to make a bold film which cast tribal people as Sree Rama, Laxmanan, and Sita, much to the surprise of ‘new wave’ Indian films. The now-famous meditative and slow style of Aravindan emerged in Kanchana Sita, giving him a new identity as a film-maker in India. The film’s genre can be categorised as philosophy, similar to those made by Ingmar Bergman, which were in vogue then. The film was a success and received national and international attention. This encouraged Aravindan and his producer to embark on further endeavours, which resulted in the black-and-white film Thampu. Aravindan soon caught the eye of master film-makers like Satyajit Ray.

In fact, during the post-Emergency period of the 70s, the youth of Kerala were mesmerised by films and related media forms. Many attempted to make films of their own, spawning a new wave of Malayalam cinema and theatre. New movements in literature, theatre, and film emerged, with new ventures by Aravindan, Adoor, John Abraham, Kavalam, Narayana Paniker, Ayyappaanicker, Kadammanitta Ramakrishnan, OV Vijayan, M Mukundan, M Sukumaran, Paul Zacharia, among others. This new wave in cultural fields led to the emergence of new and young actors like Gopi, Nedumudi Venu, V.K. Sree Raman, and Jalaja, and musicians like MG Radhakrisnan. Apart from the more well-known artists, a host of writers, theatre-artists, and film-makers were able to make their mark as well. The creative churn in the mid-70s in Thiruvananthapuram created new-age poets, writers, singers, and film-makers like Bharathan, Padmarajan Gopi, Sethu, C.P. Padmakumar, and Nedumudi Venu. Aravindan was the mascot of this cultural movement which revolutionised Kerala’s cultural field. By then, his network was not limited to just intellectuals and artists, but included hawkers, potters, and auto drivers from Bombay and Delhi as well.

Aravindan, being the son of a writer, also had friends in various cultural fields and their numbers swelled followed his entry into films. Among his friends were the likes of Padmakumar, Issac Thomas Kottukappally, Rajiv Vijayaraghavan (both FTII awardees), and EC Thomas, who assisted Aravindan in his films and contributed immensely to their aesthetics. Some of the frequent visitors to Aravindan's camps and film locations include Pavithran and Chintha Ravi, who went on to make films of their own later.

Thampu received national and international accolades, and the film was selected for many international festivals. Aravindan became an important member of the ‘new wave’ of Indian films, aided and abetted by the union government under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Till then, Adoor Gopalakrishnan was the only film-maker from South India to be recognised in European festival circuits. But now, Aravindan too was able to enter this prestigious circle with his film Thampu.

It will be of surprise to many to learn that Aravindan never worked with finely-written film scripts, like many other new wave film-makers. Many a time, he would take a slip of paper from his pocket and use that meagre description to direct how the scene is to be set and narrated. But the art director and his assistants were briefed in advance about properties and costumes. Dialogues were usually written at the location. Aravindan never hesitated to discuss themes and scenes with close friends and associates, and often accepted suggestions made by them. At times, he would hear them out patiently but would go ahead with what he had already planned.

Aravindan followed this method till Pokkuveyil, his last film with Ravi. After Thampu, Aravindan had made Kummatty and Esthappan with Ravi too. Again, the producer gave him full creative freedom, without any restrictions. The same methodology was followed in documentary-making as well.

But after a long gap, and a parting of ways with Ravi, Aravindan partnered with friends to start his own production house to make Chidambaram. It was followed by Oridath.

During this period, Aravindan had to compromise on his style and had to depend on contemporary marketing practices for the promotion of his films.

For the first time, he had to cast artists from the industry. For the film Chidambaram, Smita Patil from Bombay was hired. Getting her to act in the film was a difficult task, but she charged only Rs. 25,000 as a token fee for her performance. Shyam Benegal and Govind Nihalani also helped Aravindan rope her in, though she had already been keen to work with Aravindan and had requested him for an opportunity. It turned out that for Smita Patil, working with Aravindan and his team at Munnar was a spiritual experience, as she was going through a difficult period in her married life with Raj Babbar. Aravindan’s sage-like assistants, and friends like C.P. Padmakumar and Sethu, counselled her, and gave her much-needed relief. This led to an excellent performance, resulting in Aravindan’s most commercially-successful film— Chidambaram. Though Smita missed her final shoot at Chidambaram temple, Aravindan was able to complete the shoot with a dummy.

The film Oridath, an extension of his cartoon series Cheriya Manushynamum Valiyalokavum, was not very popular, but veteran actors like Krishnankutty Nair and Jagannathan acted in it. They had known him from theatre productions he did with Kavalam Narayana Panicker. Due to his familiarity with locations from his time at the Rubber Board at Kozhikode, he was able to identify the best locations to capture the scenic beauty of valluvanadu (Malabar region) with ease. However, after Oridath, he had to wait for Dooradarshan productions to produce Maraattam, his next project.

Monetary constraints began to affect his work during this period. As a result, this was his last work with cameraman Shaji. His team slowly deserted him, and for Aravindan the film-maker, his remaining years were like Sriram of Ramayana during Vanavasa. Unni, a little-known English film, was made with the help of an overseas producer. His last film, Vasthuhara, which he and a friend Ravi (bank Ravi) produced, led to a great deal of stress as they had procured unsecured loans to make the film. It will not be far from the truth if I were to say that his death was caused by the complexities that arose from the financial crisis and his friends deserting him.

Aravindan turned to documentary film-making in a bid to improve his financial situation, as he had resigned from the Rubber Board. The Film Division and the Festival of India, as well as other agencies, were glad to commission him to make films on various themes.

Pupul Jayakar, who was fascinated by Aravindan’s early films and his mystic attitude, encouraged the Film Division to commission a film by Aravindan on J Krishnamurthi. Similarly, Aravindan made a documentary on artist Namboodiri for Chalachithra Film Society of Thiruvananthapuram. The move reflects his deep commitment to the film society movement. He had been a regular in the film society screenings of Chalachitral and Chitralekha from 1975—and before that, of Aswini Film Society of Kozhikode. To mark their deep appreciation for his support, Chalachithra introduced an annual award in his honour—the Aravindan Puraskaram— after his death. The award continues even today, making the film-maker a legend of our times.

Aravindan spent most of his time on post-production activities, which included editing, dubbing, music production, and sound mixing. He prioritised content, visuals, and music, rather than craft in his films. Being an untrained film-maker, he knew that his strength lay in his creativity and unique perspective, and not the craft of the film. Though he had a trained crew, they too were swept away by his ideas, and they chose to play second fiddle to his content and vision. Once he finished a film, he would preview it to his very close friends, and would also make a collective plan to promote the film. Aravindan never sat with guests during screenings and never discussed them as part of his promotional efforts. His quip to friends was that, ‘Once the film is made, it will speak and not the film-maker’.

Aravindan nurtured a community of cultural activists, who pursued a variety of fields, including film-making. His cinematographer, Shaji N Karum, ventured into film-making on his own, and CP Padmukar, his long-time assistant, too made films. Aravindan strove to support close film-making friends by nominating them for national and international film festivals. He would also engage in deep discussions with critics and other film-makers about the films he liked. Often, he would get involved in films made by his friends and even composed the music of Shaji N Karun’s film Piravi, as well as Chintha Ravi’s Ore Thooval Pakshikal, and Pavithran’s Yaro Oral.

Aravindan remained a down-to-earth person, despite being a film-maker of international repute. Hailing from a middle-class background (his father was a lawyer by profession), he helped many of his friends get placed in different fields, and remained a friend in need to all those who were around him. He never hesitated to call upon people of high standing, in order to help needy friends. This gave him a huge fan following in Kerala and elsewhere.

Politically, Aravindan stood with the Left and never made any bones about it. He did not hesitate to participate in a Kerala-wide human chain organised by DYFI, the youth wing of CPIM, as a part of a campaign to promote secularism and the unity of the nation and mankind.

He was very conscious of his persona and was fond of cotton clothes. The six-foot tall Aravindan was a brand ambassador for cotton and batik shirts in Kerala, which become a rage among would-be artists and intellectuals. During his visits to Bombay, he would make it a point to visit fashion street to buy shirts, and the music store ‘Rhythm House’ at Kala Ghoda. The hawkers used to set aside extra-large shirts with the latest designs for him. He would buy them for his favourite friend, the still-photographer, NL Balakrishnan, who had a huge build. At Rhythm House, Aravindan would buy cassettes of Hindustani musicals for his friend, SP Ramesan, and me.

He loved to be called Aravindan even by youngsters, but for many, he was Aravindettan (elder brother Aravindan) and Guruji (great teacher).

Aravindan was the son of lawyer MN Govindan Nair, a cartoonist and satirical writer. He had two brothers and a sister. Born in 1935, during the British Raj, he left his home town of Kottayam, which was known as the publishing capital of Kerala, at an early age of 17. He completed his graduation at University College, Thiruvananthapuram. Around that time, Aravindan had started the Film Society at Kottayam and was also associated with the Chithralekha and Chalachitra film societies of Thiruvananthapuram.

His college-mates included a painter, A Ramachandran, and a writer, N Mohanan. A Ramachandran, who went on to study at Rabindranath Tagore‘s Shantiniketan, introduced Aravindan to Rabindra Sangeet, Bengali cinema, and Bengali art. Aravindan popularised Rabindra Sangeet in Kerala by singing them in most of the functions he was invited to. He usually refused to speak at public functions, but he would agree to sing. The Bengali influence is visible in his cartoons, and his last film has a Bengali-Malayalee theme, as the plot involves a marriage of a comrade with a Bengali lady and the nephew’s effort to locate the uncle’s lost family and cousins.

Aravindan joined the Rubber Board as a development officer and got the chance to travel across rural Kerala and to understand the lives of the common people. Rubber happens to be the backbone of Kerala’s plantation economy. This helped him understand and empathise with the people around him.

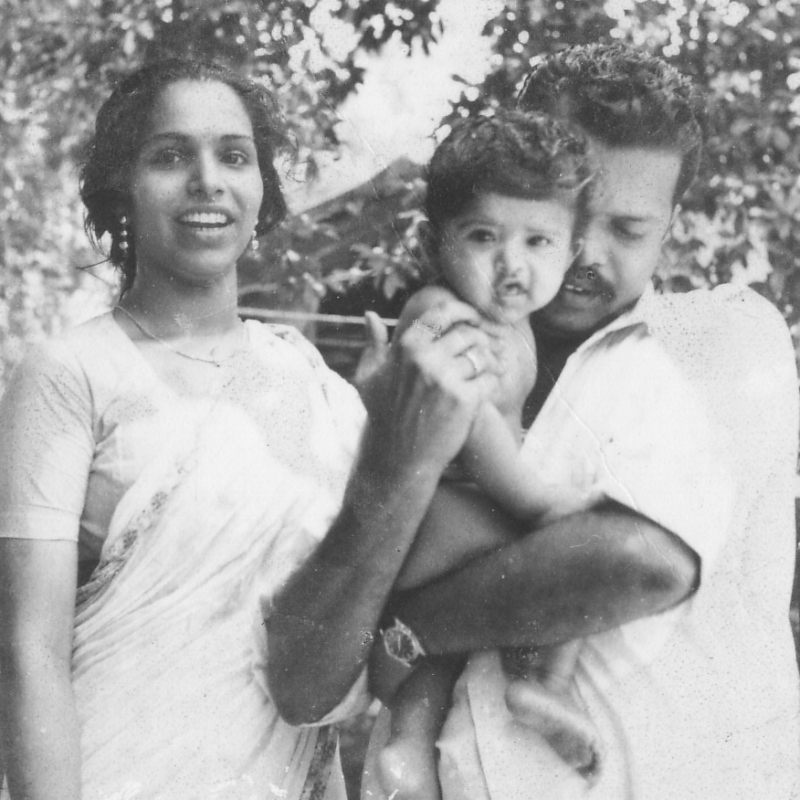

During his stint at Kottayam, he found his wife, Kaumudi, who was also working in the Rubber Board. They have a son, Ramu Aravindan, who is a well-known designer and still-photographer. He works in Bengaluru now.

Aravindan died of a massive heart attack in 1991.